By Raymond Chong

INTRODUCTION

Moi Chung, my paternal grandfather, hailed from Hoyping of the Sye Yup region of Kwangtung, China. As a sojourner to Gold Mountain, he owned two Chop Suey Houses, the Royal Restaurant and Imperial Restaurant, from 1917 to 1936. Chop Suey was a popular Cantonese cuisine in Chinatowns and downtowns across America.

During Chinese Exclusion Act, job opportunities for Chinese as sojourners in America were very limited. Chop Suey houses, as well as hand laundries and dry goods stores, was their basic means to earn a living. Chop Suey was a key aspect of the Chinese experience in America. It reached its zenith between 1896 and 1965 as cuisine for Americans. Moi Chung followed that business pattern.

HOYPING

LATEST STORIES

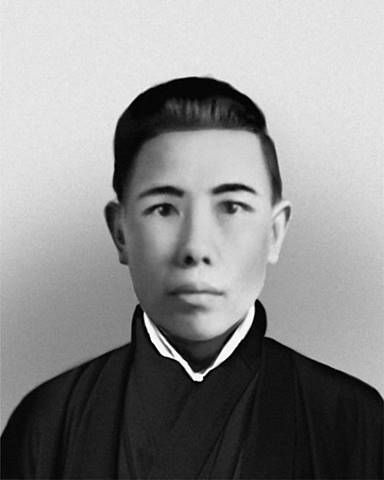

Born February 8, 1892, Moi Chung hailed from Yung Lew Gong of the Pearl River Delta.

Hoy Lun Chung was his father and Shee Lee was his mother. In about 1892, Hoy Lun Chung went to Gum Saan. He operated a gambling hall and opium den in Boston Chinatown. In 1926, he returned to Yung Lew Gong, a very wealthy man. He built a house there and owned a market in Toishan (Taishan).

Hoy Lun Chung wanted Moi Chung, to carry on his success in America. He had business investments in San Francisco, Cambridge, and Springfield. Moi Chung married Shee Leung, wife #1, who allegedly died early in their marriage. Together, they had a daughter, Suey Fong Chong, born in 1912. They also had an adopted son, Bow Fui Chong.

SAN FRANCISCO CHINATOWN

Moi Chung immigrated from Hong Kong to Gum Saan. He arrived at the Port of San Francisco in California on June 17, 1912 aboard the S.S. Mongolia steamer. She carried 1,818 passengers, grossed 13,639 tons, with a speed of 16 knots. He was briefly interviewed at the Angel Island Immigration Station. Moi Chung attended Ng Lee Mission School under sponsorship of Miss Ida Greenlee. He worked at the Jeang Sing Kee Company at 658 DuPont Street (now known as Grant Avenue) in San Francisco Chinatown It was a seller of Chinese dry goods and food products. Moi Chung would later become a silent partner in the company with his father.

NEW ENGLAND

Moi Chung moved to New England to work as restaurant manager at his father’s Imperial Restaurant in Cambridge from 1917 to 1919. It was near Boston Chinatown, the center of the Chinese community in New England. Moi Chung lived and worked among a bachelor community of few women and few children. They were a fraternity of brothers who left their wives in China.

Because of the severe restrictions on female immigrants and the pattern of young men migrating alone, there emerged a largely bachelor society in Chinatown. The family of Moi Chung was forced apart, separated from 1923 to 1966 – 43 years, from Cun Chuen Wong, my grandmother. Bitter agony for the “bachelors” in Chinatown while pursuing their lofty dreams on Gold Mountain. Letters were they only means of communication across the Pacific Ocean.

In 1919, Moi Chung would take after his father and become a partner with a $500 share of the Royal Restaurant in Boston Chinatown. He was a partner from 1919 to 1921. It was a first-class restaurant serving Chinese and American customers. The Royal Restaurant was on two floors with 100 seats. Moi Chung was restaurant manager. Royal Restaurant was generating $6,000 per month in sales. Moi Chung received a $90 monthly salary.

Many Chinese businesses were capitalized by investors, whether in active (management) or passive (silent) roles. Federal immigration inspectors viewed management of a business as qualification for merchant class under Chinese Exclusion Act. It allowed them to legally return to America after their visit to their hometowns in China. If a sojourner was deemed a laborer class, he was not allowed to return.

Moi Chung returned to China as a merchant for the Royal Restaurant. He departed on June 16, 1921, from the Port of Vancouver, aboard R.M.S. Empress of Asia. He returned to Yung Lew Gong Village, where he married Cun Chuen Wong, wife #2, from Toishan, on December 1, 1921. Gim Suey Chong, my father, was born on December 26, 1922.

Moi Chung returned to America from the Port of Hong Kong aboard S.S. President Grant. He arrived at the Port of Seattle on July 9, 1923. Moi Chung became a partner and restaurant manager of the Imperial Restaurant in Central Square of Cambridge on December 1, 1923. The Imperial generated $4,000 per month in revenues. Moi Chung received $100 monthly salary as restaurant manager.

The Imperial Restaurant was a high-class fancy restaurant with white cloth tables served by waiters on the second floor of the Holmes Block, a three-story brick block with mansard roof. It was known for Chinese and American dishes, especially Chop Suey. They served turkey for lunch on Sundays. There were three dining halls, kitchen, and storeroom. It had the capacity to seat 170 people. One white employee was porter. Another time, they had three white girl waitresses.

Central Square centered on the junction of Massachusetts Avenue, Prospect Street, and Western Avenue. Several Cambridge neighborhoods meet at Central Square. Central Square is the seat of government in Cambridge – Cambridge City Hall, the Cambridge Police Department, and Cambridge Post Office is in this area. Central Square was known for its wide variety of ethnic restaurants and bars and commercial and retail center for Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

By 1932, his son, Gim Suey Chong, was 9 years old. Moi Chung decided it was time to bring him over. He was given false papers to bring him to America, where he would have better opportunities for a good education and a higher income. Gim Suey Chong memorized the biographical information associated with his paper identity and successfully gained entry, on April 25, 1932, at Port of Boston.

However, father and son struggled to make ends meet, even though they lived in quarters above the restaurant to save money. Like many businesses, the Imperial Restaurant did not do well during the Great Depression. The economy was in shambles. Jobs were scarce across the country. Moi Chung decided to sell his share in 1936 and move to Los Angeles.

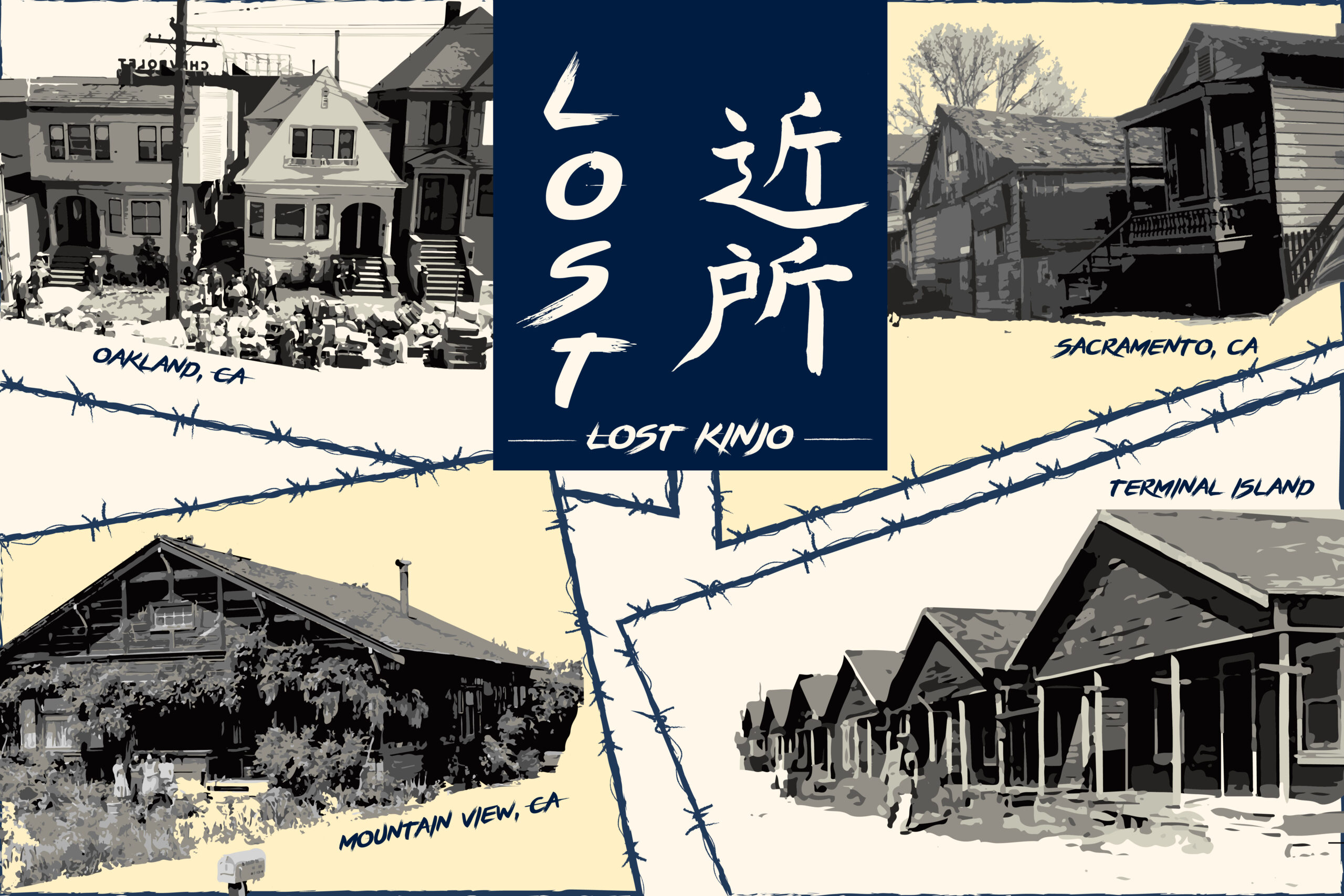

LITTLE TOKYO

In summer 1936, Moi Chung and Gim Suey Chong left New England for a new life in California – The Golden State. With their meager possessions, they departed from the South Station of Boston to transit thru the Union Station of Chicago. They finally arrived at the old Central Station (Southern Pacific/Union Pacific Railroad ) near City Hall in Downtown Los Angeles.

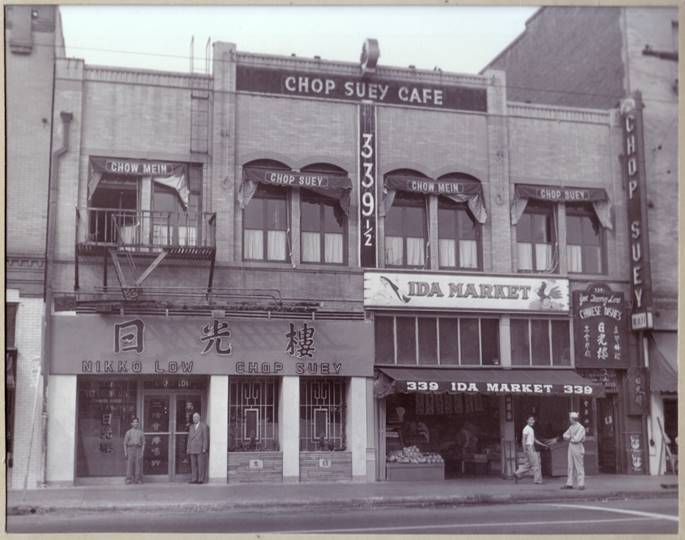

The bustling Little Tokyo was the biggest enclave of Japanese in America. From 1936 to 1943, Moi Chung worked as a waiter at café of Yet Quong Low (“Sun Light Building”) Chop Suey Café . It was also known as Nikko Low Chinese Restaurant among the Issei and Nisei community. The Café specialized in the Japanese version of Chop Suey – “China-Meshi.” Hoie Wing Jung was owner, who also was from Yung Lew Gong. Other Chop Suey restaurants in Little Tokyo included the famous Far East Café, Sam Kow Low Chop Suey Cafe, and Lem’s Café. They slept in the storage room.

Yet Quong Low had a banquet room for up to 200 people. A dining room of six tables was in front. They served chow mein, beer, and wine. Japanese farmers were regular customers after they delivered fruits and vegetables to the Produce Market. They enjoyed drinks and entrees at the Chop Suey cafes on Saturdays. The adjacent Far East Café was a rival.

LAST YEARS

Moi Chung associated with his fellow clansmen from Hoyping at the Wai Sing Meat Company. They shared their hopes and dreams. They missed their wives and children in China. They wrote letters back home, talk gossip, and play games. His best friend was Dong Foo Jung, a watchmaker, at Paul’s Jewelry on Broadway in Chinatown.

Moi Chung drifted into casual jobs as a waiter, bartender, and cook at various restaurants in Los Angeles and San Francisco. After retirement, he received a meager Social Security check. His lonesome misery and agony led to his chronic alcoholism, that was worsened by the long separation from Cun Chuen Wong, his wife, due to Chinese Exclusion Act.

In Los Angeles, Moi Chung was naturalized as an American citizen, with Certificate of Naturalization, on September 21, 1953.

With the help of California Representative George Edward Brown, Jr., via an IR-1 spousal visa, Moi Chung reunited with Cun Chuen Wong, on February 14, 1966, at Los Angeles International Airport after a long separation of 43 years. For ten years, they quietly lived together at a bungalow in Elysian Valley.

My love poem below reflects the love of Moi Chung for Chun Chuen Wong at America.

A LONG-LOST LOVE

By Raymond Douglas Chong

During a restless sleep in Gold Mountain

Claps of a thunderstorm awaken me.

My dreamy mind recalls

A long-lost love that I left in Hoyping.

Why can we not share our lives?

Why can you not stay with me?

Why can you not feel my love?

Why are you so far away from me?

I will never depart from you

I will never say goodbye

I will never love another woman

I save myself for you.

The health of Moi Chung and Cun Chuen Wong gradually declined. With deep angst, Gim Suey Chong, their son, reluctantly placed them at a nursing home in Los Angeles. Moi Chung died on August 3, 1976, and Cun Chuen Wong died on October 24, 1977, at the French Hospital with Dr. Julius Sue in attendance. Gim Suey Chong sadly buried them, among other sojourners, at the Chinese Cemetery in East Los Angeles.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff or submitting a story.