By Monique Mun, M.D.

It was a usual study night for me in college. I was studying for a mid-term in one of my frequented spots – the student commons building across my door room. I often studied alone, but enjoyed the environment of having other students around me studying. It kept me on task. I received a call from my mom, not an uncommon occurrence, and reflexively answered, “I’m studying right now, can we talk in a few hours?” My mom, being the biggest supporter of my education, would usually respond by saying “okay, okay, talk later” and hang up the phone. This time, my mom stayed quiet. It was the silence that signaled to me something was wrong.

My mind was frantic and I started searching for all the possible scenarios of what could be wrong. Car accident. A fight in the family. Health issue. Even as “health issue” had crossed my mind, I was thinking of my father, an asthmatic, hypertensive meat-lover, and not my grandmother. I knew my grandmother had recently been moved to a nursing home due to her escalating level of care – a decision that indicated how her health had rapidly deteriorated. Nursing homes don’t exist in the Chinese culture. When we become adults, we take on the filial duty to take care of our parents into their old age. We accept our parents into our homes and in turn, they help look after our children. It was when my mom said, “you need to talk to your grandmother”, that I knew exactly the purpose of this call. I needed to say goodbye to my grandmother.

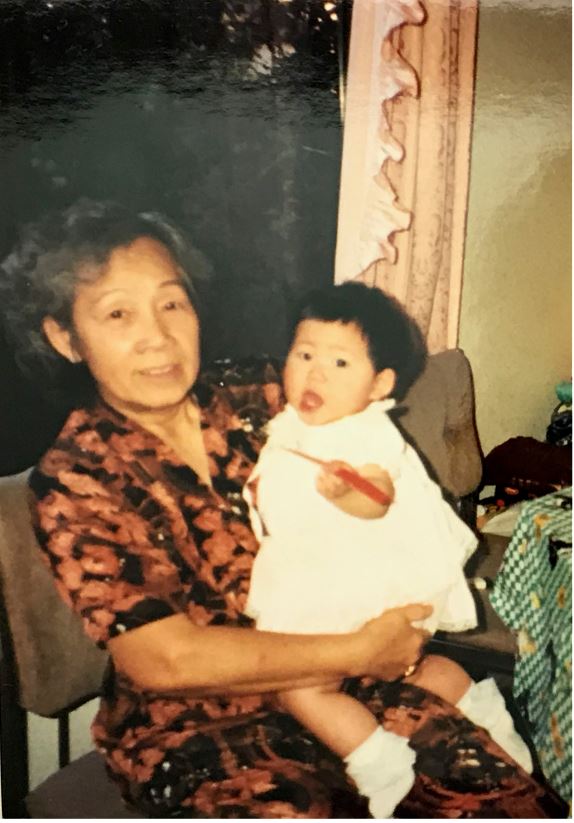

The earliest memories of my childhood were with my grandmother. As a child of Chinese-Burmese immigrant parents, I was left to the child-rearing of my grandmother while my parents worked long hours during the day. My grandmother was not warm in the sense of how grandmothers typically are in Western cultures. She did not spoil me or pepper me up with compliments by calling me “cute” or “pretty”. Instead, she was traditional and firm. Instead of letting me tune into kids shows in the morning, she would have me sit next to her while watching Chinese historical drama shows. During the day, one of my chores consisted of cutting vegetables in preparation for dinner, which she would then scrutinize for size and consistency. In the evening, when she would bathe me, she would pour scalding hot water over my body. As I winced, she would quickly rub my skin and say in Mandarin, “you will get used to it, you will get used to it”.

My grandmother had a love that was tempered and reserved.

LATEST STORIES

When she was diagnosed with cancer – a diagnosis that can be tragic and fatalistic for some – it didn’t seem to devastate her. For my grandmother, it was something she needed to get through and not succumb to. Soon after her diagnosis, the timeline of events of her medical care became a blur to me. I would hear from my parents the painful process she would go through – the bone marrow biopsy, the daily blood draws, the sickening effects of chemotherapy. She never showed pain or suffering on her face, at least not to me. When I went with her to one of her doctor’s appointments for her weekly blood draws, I observed her as she watched the phlebotomist prepare her arm for the needle insertion. I followed my grandmother’s lead and kept my gaze on my grandmother’s arm. My grandmother looked to me and said, “turn away!” right before the needle broke skin, and I obediently turned away and shut my eyes. When I turned back, I wondered if it was painful for her. Round after round of chemotherapy, my grandmother was shrinking in size. Her bones were now showing through fragile and bruised skin, and the few strands of hair left on her head were thin and gray. The family matriarch who was once cooking family meals, squatted for hours while gardening, and yelled with angry passion when one of us grandkids misbehaved, now sunken into the shadow of her diagnosis.

Christmas of 2007 was the last time I had photos together with her before I moved six hours away to start college at UCLA. That Christmas I had gifted her a pink knitted wool hat. In Chinese culture, there is a fear of getting a cold from heat rapidly escaping from the head. Children and elderly are especially susceptible. My grandmother often wore hats due to hair loss from the chemotherapy – it seemed to be more at the insistence of my gay older cousin who turned her hair situation into an opportunity to accessorize while still being practical. I would never get to see her wear the pink knitted wool hat.

That night, when my mom called me to say goodbye to my grandmother, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of shame. How could I be here, studying for a mid-term, instead of being at home with my grandmother, who is possibly dying? As all the private study rooms were occupied, I discreetly tucked myself at the end of a secluded hallway. “What is going on?” I asked my mom. My mom’s voice was strained, as if she was fighting to hold back emotions as she was re-telling me the events of the day. My parents received a call from the nursing home, recommending that they come in to see my grandmother. Her heart had stopped and they performed emergency CPR on her without success. She was on a ventilator, which was the only thing keeping her breathing. My mom listed in order relative after relative whom had filed in to surround my grandmother in her last moments. My aunt, Da gu ma (Mandarin for eldest aunt), was the oldest of grandmother’s children. Thus, she was appointed as the medical decision maker for my grandmother. My Da gu ma wanted to keep her living, even artificially on the ventilator, for as long as possible, but the nurses had advised that there was essentially no hope for my grandmother. Even as I was hearing this over the phone, I could feel the internal conflict my Da gu ma must have wrestled with. She was weighing a medical decision against her cultural upbringing. She must have felt that pulling the plug equated to giving up on my grandmother’s life. It felt wrong as the dutiful eldest daughter to “give up” on her mother. Yet, she knew there was no dignity in letting my grandmother’s lungs be repeatedly pumped by the ventilator, indefinitely.

My mom put the phone to my grandmother’s ear and I could hear my mom say to my grandmother, as if she believed my grandmother was alive and could hear, “this is Monique, this is Monique” in Mandarin. With my broken, accented Mandarin, and tears streaming down my face, all I could bring myself to say was, “this is Xiao li (my Chinese name), this is Xiao li”. I wanted to let her know that I was there. This was the only sentiment I could express due to the sparsity of my Mandarin vocabulary – whilst grappling with newly-formed grief. My mom passed the phone to my cousin, as if my mom wanted to relieve herself from the emotional toll of being a conduit for my grief. I heard sobs on the other end and I knew it was my cousin, the one who went to all my grandmother’s doctor appointments with her. There were no words exchanged between us. We stayed on the phone and cried together.

They pulled the plug.

Here I was, in a public building, full of students, on a college campus, and I felt completely alone. It was like my world had stopped, but others around me kept going.

The following weekend I had flown back to northern California for my grandmother’s funeral. I was with my sisters and cousins, who were all looked after by my grandmother at various points in their childhood. We sat around and shared our favorite memories and stories of her. It had confirmed what I knew all along – that my grandmother was incredibly strong, brave, stubborn at times, but fiercely loving of her grandchildren. She had a tough kind of love.

I can say being raised by my grandmother has instilled in me the qualities and characteristics that make me who I am today. How I have persisted through decades of formal education to become the first physician in my family. How I identify myself as feminist, a leader in my profession, an advocate for minorities in healthcare, and a mentor for aspiring physicians.

I imagine if my grandmother were still alive today, she would not be moved by my accomplishments. In her mind, she would know I was capable of achieving these things all along.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story

RE: A personal journey: Saying goodbye to grandma: A very poignant memory of grandma.