By Julia Tong, AsAmNews Staff Writer

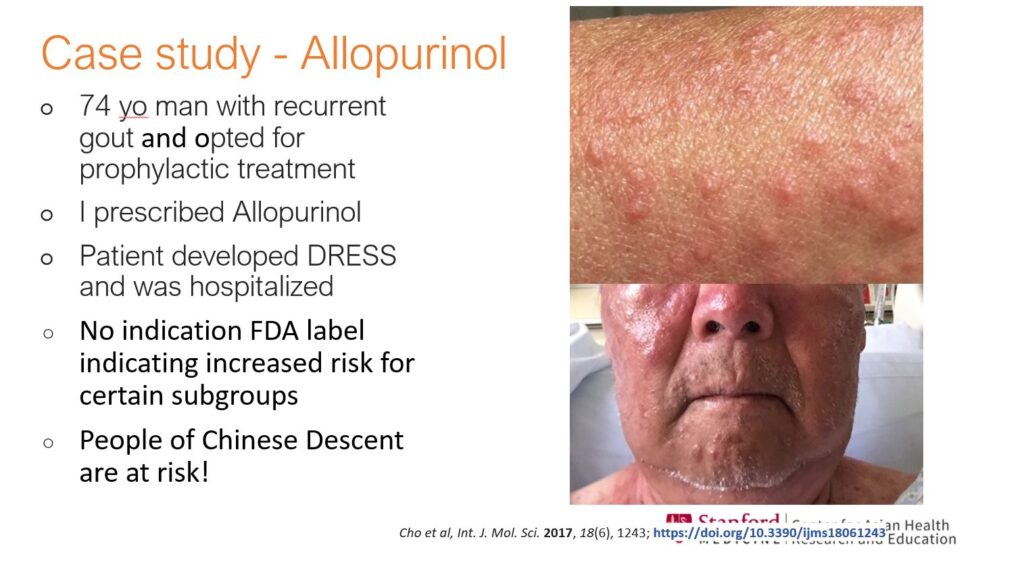

When Dr. Bryant Lin treated a Chinese American patient suffering from gout, he prescribed a standard medication called Allopurinol. However, the patient developed a skin reaction to the drug, or DRESS, that was severe enough to require hospitalization.

At the time, Lin didn’t know that people of Han Chinese descent had a genetic factor that raised their risk level for DRESS after taking Allopurinol. FDA labels didn’t indicate the increased risk, despite the information being well known in Asia.

“This is really the importance of understanding what the risks are for Asians. But it’s not all Asians—it’s specifically… people of Chinese descent,” he said. “And this is something we can test for, or give an alternative medication for, so this skin reaction is potentially preventable.”

Lin’s case study illustrates the necessity of having information on specific Asian American subgroups for accurate medical treatment. In a recent panel held by Ethnic Media Studies, sponsored by Stanford Medicine’s Center for AAPI Care and Research (CARE), Lin joined three other medical professionals to discuss the importance of disaggregated medical data. They say that this data, coupled with culturally competent care and multilingual education, is necessary to close long-standing medical inequities in the AAPI community.

LATEST STORIES

The first layer of the issue, Lin points out, is that Asian Americans are often not identified in medical data at all. Instead, they’re frequently lumped into one category: “other.”

Primary care physicians use the ASCVD Risk Estimator calculator to determine whether to prescribe Lipitor, a statin used to treat high cholesterol, to patients. Though the calculator takes race into account, it only offers three options: white, African American, and “other.” As a result, the calculator may underestimate risk for groups like Asian Indians, who are at higher risk of heart disease, and overestimate for others, such as East Asians.

“‘Other’ is a huge, huge bucket,” Lin said. “And we have to do better than this.”

The reduction of Asian Americans to “other” was especially problematic throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Winston Wong served on the Advisory Committee on Minority Health during the beginning of the pandemic. For the first 6 months, he recalled, at least 25 states didn’t identify “Asian American” as a separate group in data—not to mention Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian.

Instead, those states frequently categorized Asian Americans as “other.” As a result, the impact of COVID-19 on many vulnerable communities was overlooked. In New York, for example, the biggest group of hospitalized individuals for COVID were Chinese American. The Bangladeshi community in New Jersey was also disproportionally affected. And in Arkansas, the group with the highest rates of COVID hospitalization were the Marshallese community, who lived in crowded spaces and worked high-risk occupations such as poultry farms.

“This kind of data is only identif[ied] at this point by the activists, the community providers, the physicians and nurses who care for that community, because they’re providing the culturally competent and linguistically accessible care to these populations,” Wong says.

“But it’s not necessarily getting captured at the statewide level that gets rolled up to make national headlines, and to make a national priority around COVID in the subgroup.”

Having data that is disaggregated by specific ethnic background available, however, can inform targeted interventions that benefit marginalized communities.

Dr. Thu Quach is the President of Asian Health Services (AHS), a federally qualified health care clinic that serves thousands of Asian Americans in San Francisco’s East Bay counties. In July 2020, AHS got funding from Alameda County to provide COVID testing to underserved AAPI communities. Assembly Bill 1726 also required all health data in the state to be disaggregated by Asian American ethnicity or background.

The disaggregated data allowed AHS to identify a particularly vulnerable community: Vietnamese Americans tested positive at twice the rate of everyone else. According to Quach, many residents in the community were low income, had limited English proficiency, and were at a higher risk of COVID due to living in crowded housing and relying on food distribution sites.

With this information, AHS was able to expand culturally informed testing, outreach, and education to Vietnamese Americans. They opened a testing site outside Little Saigon in Oakland and were able to supply the community with vaccines when they became available.

“With the limited resources that we had, we were able to have targeted interventions with the most impacted group at that time,” she said. “And this is why disaggregated data matters, not just in identifying the problem, but in providing timely responses to address such problems.”

However, Quach also stresses that data by itself isn’t enough for outreach: Language proficiency and cultural awareness are necessary to create successful interventions.

According to Dr. Van Ta Park, a professor at UCSF, those language and cultural barriers result in Asian Americans being significantly underresearched in medical literature. Only 0.17% of studies in the National Institute of Health’s database, she says, were focused on AANHPI participants.

To combat this problem, Park helped found CARE (not to be confused with Stanford University’s Center for AAPI Care and Research), a culturally research registry for Asian Americans. The registry featured enrollment for adults in multiple languages, including but not limited to Mandarin, Hindi, Korean, Vietnamese, and Samoan. Participants fill out a 10-15 minute survey online, by phone, or in person, and can receive a $10 gift card for their time.

Park hopes to recruit 10,000 people to the registry. And she’s close to her goal: CARE has recruited nearly 9,300 adults, with 81% reporting no previous participation in research. Of those, 5,530 have been referred to 27 studies, 24 of which have study materials in at least one other AANHPI language.

“If we do the outreach, if you go to the community and provide the education, and really amplify the messages about the importance of participating in research, then many people will sign up and enroll and understand that message,” Park says.

Progress has been made since the beginning of the pandemic: the NIH now disaggregates data by Asian American subgroup. However, panelists stressed that this data must be accompanied by culturally informed communications.

“It’s about implementation, implementation, implementation,” Quach says. “What’s really important is…to focus on how the Department of Public Health will require that people collect data in its disaggregated form, and beyond that, that they’re actually communicating out to the public.”

Wong stresses that multilingual, transparent communication of data from government agencies and other sources is critical. He had previously refused to be part of what he describes as the NIH’s “process of so-called reaching out to the Asian American” community, when the organization would not provide funding for outreach in Chinese and other Asian languages.

“When the NIH says we’re doing a great program to develop precision medicine to reach every American, but they don’t make that knowledge of that program available in any other languages besides Spanish and English, [it] is a hypocrisy to say that they’re reaching all of us,” Wong says.

Continued advocacy is necessary for substantial changes to occur, he adds.

“There is a role for us to be pretty hard critics and advocates for the issue of disaggregation.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.