By Ed Shew

(Editor Note: Ed Shew is the author of Chinese Brothers, American Sons)

“Mother must have loved me; she gave me rice.” That lamentable plea, that tear in her voice, is told without rancor by my mother Rose Yee Shew about her mother, Nong Yee.

That love by Rose’s mother sustains her when there is barely enough food to feed Rose and her three brothers (Hackman, Dickman and Jackman) and her two sisters (Lily and Marie) during the grinding poverty and the clouds of melancholy of The Great Depression that ravages America from 1929 and some say, into the 1940s of World War II.

After a decade of frenzied stock market speculation, the bubble bursts. On October 24, 1929, “Black Thursday,” the first great crash on Wall Street, is followed by a series of secondary shocks, and then a long, sickening slide toward a national depression. The effect ripples away from New York deep into

the hinterlands of the country and into St. Louis’ Chinatown, also known as Hop Alley, shutting down banks and putting companies out of business.

LATEST STORIES

In 1930 the national unemployment rate rises from 3.2 percent to 8.7 percent; in St. Louis it rises to 9.8 percent. By the spring of 1933 the national unemployment rate reaches its peak of 24.9 percent, in St. Louis it is 30 percent.

As money grows tighter, Chinese families, like millions of White families, have to make do with less. With economic prospects vanishing, many return to China. In Missouri the Chinese population decreases from 634 in 1929 to 334 in 1939—Chinese hand laundries fall from 165 to 89 in the same period.

In 1930 there are 350 Chinese in the City of St. Louis with a population of 820,960, according to U.S. Census Bureau reports.

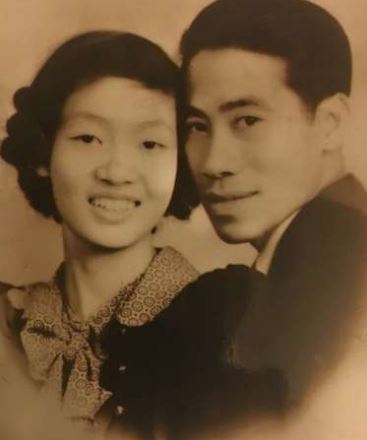

Born as Ganlan Nina Yee (her Chinese name) in St. Louis’ Chinatown in 1925, my mother Rose is the oldest daughter and is second oldest of six children of her mother, Nong Yee (1893-1940) and her father, Weeget Yee (1880-1950). Her parents live in Chinatown and run a Chinese hand laundry on

Chinatown’s fringe.

My mother works before and after school and on weekends, six or seven days a week. She toils long hours in the stifling heat, wields a heavy 8-1⁄2 pound iron and presses white shirts for white customers. She is so tired she often misses school.

While my memories of mother Rose Yee Shew are scattered like shards of broken glass, I piece together newly-found time frames of a 1940 puzzle, a fateful, heart-breaking year for my mother, full of chilling, life-sentencing events.

Mother’s escape at 15 years old from the sweat-shop conditions of her family’s laundry is an arranged, loveless marriage in 1940 with my father, Jimmy Lee Shew, 30.

That same year, 1940, Rose’s mother dies of cancer. That bond is torn away leaving a multitude of strong emotions mother may have, such as, numbness, confusion, fear, guilt, and anger.

But there is no respite, a sister Lily, born in 1929, is not on the family census of 1940, perhaps the year she is sold by Rose’s father, a gambler and an alcoholic who commits suicide in 1950.

That connection between Rose and Lily is unlike other relationships, because nobody other than Lily is raised in the exact same way. Being raised in the same environment offers Rose and Lily a way to be comfortable and relate to each other like no one else can.

Rose teaches Lily how to tie her shoes; they even share a bed. However, that sisterly affection and trust, that influence on development and mental health, is ripped away, also.

Those broken bonds become voids in my mother Rose’s life. Sometimes that emptiness may be reparable, but in her case, the damage is so extensive that it is irreparable.

To be continued….

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.