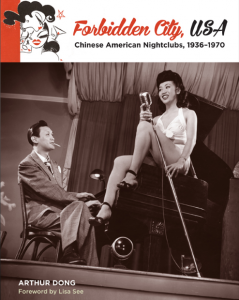

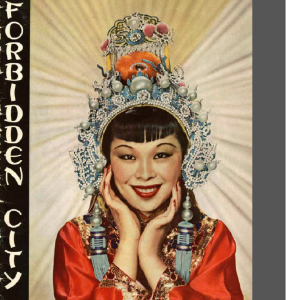

The Chinese Historical Society of Southern California will host a discussion with Arthur Dong about his new book Forbidden City USA this coming Wednesday, June 4 at 7pm at Castelar Elementary School (photo from Chinese Sky Room).

The Chinese Historical Society of Southern California will host a discussion with Arthur Dong about his new book Forbidden City USA this coming Wednesday, June 4 at 7pm at Castelar Elementary School (photo from Chinese Sky Room).

Free parking is available in the school yard lot via College Street. Castelar is located at 840 Yale Street in Los Angeles.

Dong took time from his hectic schedule to answer a few questions from AsAmNews.

Where does the name Forbidden City, USA come from?

I was braining-storming with my sister and brother-in-law, Lorraine Dong and Marlon Hom (professors at the Asian American Studies department of San Francisco State University), on a title for my 1989 documentary on the Forbidden City nightclub. The initial idea was to title it simply “Forbidden City” but then Marlon suggested adding “USA” at the end to distinguish it from the palace compounds in Beijing. That idea also underscores the metaphor of the club as a bridge between different worlds. Since then, I’ve noticed other titles using the “USA” tag over the past 25 years, and I think we were one of the first to do so.

What period of time does the book cover and what was it about this period of time that made this all possible?

Were these clubs run by Chinese Americans or by non-Asians?

What other cities did you find the Chinatown Nightclub scene? If it was unique to San Francisco, why do you think that was so?

What other cities did you find the Chinatown Nightclub scene? If it was unique to San Francisco, why do you think that was so?

What role did racism play in the existence of these clubs?

Why do you think the nightclubs in Chinatown faded away?

You devoted 30 years of your life to this topic? Why were you so passionate about this subject.?

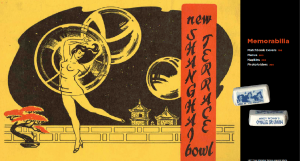

I was born too late to experience the clubs first-hand, so I’ve been trying to do all I can to be a part of the scene. The memories, postcards, menus, snapshots, programs, and meticulously crafted studio photos I’ve collected are a way to immerse myself into an era before my time–in all the senses: the looks, the sounds, the feels, the smells, the tastes. Also, the personal stories are inspirational and such a revelation: I’m the son of traditional working-class immigrants and the performers led lives so unlike the elders that I grew up around.

Can you tell the stories of any Chinatown nightclub entertainers who became famous outside of Chinatown?

Cast in film version of “Flower Drum Song” (1961), which was set in a ficticious San Francisco Chinese American nightclub, was Jack Soo, who was a former Chinese Sky Room and Forbidden City entertainer. Soo went on to a successful career in television like “Barney Miller.” Other entertainers who crossed over into the mainsteam include Sammee Tong (“Bachelor Father”), James Hong (“Blade Runner,” “Big Trouble in Little China”), Robert Ito (“Quincy”), and, most famously, Pat Morita (“Karate Kid”). And then there’s 1960s superstar Nancy Kwan, who, although not a veteran of the clubs, co-starred with Jack Soo to portray a nightclub dancer in the “Flower Drum Song” film.

What do you want people to take away from your book?

What do you want people to take away from your book?

There’s a specific image that embodies an underlying spirit in the book: It’s the cover of a Forbidden City program. Dancer Lily Pon is in a cheesecake pose, scantily dressed, and the text reads: “Your program for the evening: Come along with me please! I’ll show you how to have fun—in Chinese.” This juxtapositioning of image and dialogue takes on a tongue-in-cheek attitude, co-opting racially motivated ideas and poking fun at them.