My parents’ families are from Shandong province in China, located on the northeast coast of the country. Dumplings (水餃), filled steamed buns (包子), noodles and garlic are commonly associated foods from this region. For me, Shandongnese food is my main gateway into understanding Chinese culture.

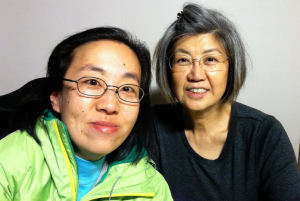

I had the opportunity to interview my mom for Center for Asian American Media and StoryCorps San Francisco’s collection of Lunar New Year food memories.

During our 40-minute recording session last week, I asked my mom a few questions:

• How did you celebrate Lunar New Year as a kid?

• Why is this holiday so meaningful to you?

• What kinds of dumplings did your family make?

• How did you learn how to make dumplings?

• How did you continue those food traditions after you emigrated from Hong Kong to Indiana in the 1970s without the same ingredients?

I focused on our family’s tradition of making dumplings with Chinese chives (韭菜水餃). We make them on special occasions and always on Lunar New Year Eve. For those unfamiliar with Chinese chives (韭菜), they look like long blades of grass and are extremely pungent. Raw chives are pungent and after cooking them in dumplings they can stink up a refrigerator. The smell rivals kimchi or stinky tofu. As with any of these foods, chives may stink, but they taste damn good (especially leftover dumplings fried as potstickers the next day with a bowl of congee)!

What I love about dumpling making is the sense of teamwork and a shared goal. Similar to a tamalada, the whole family gets together and everyone takes part in the creation of the dumplings while mom is the general in charge of the dumpling filling (no one has yet attempted to take her place) and dough making. Once the dough is made, mom hands off the dough for dad who divides them into workable pieces, rolling each ball into long half-inch thick ropes. These ropes are then cut into 1-inch pieces that are then individually rolled into a round dumpling wrapper. Throughout the entire process, flour is sprinkled to avoid sticking. All of the implements we use are old school—we have this wooden ‘rolling pin’ stick that mom swears you can’t buy anymore. The wrappers are then gently tossed toward the family members in charge of wrapping—mom and my two sisters, Emily and Grace. Both of my sisters know how to roll the dumpling wrappers, but they also excel in the actual filling and pinching of the dumplings.

The application of the dumpling filling (chives, minced pork and shrimp, ginger, soy sauce and other top-secret ingredients) in the center of the dumpling wrapper is an exercise in grace and agility. After decades of experience from her mother and mother-in-law, mom is the master dumpling filler-and-pincher. She puts an amount of filling that’s almost too much. but she is able to simultaneously stretch the wrapper enough so there’s room while using her fingers to seal the dumpling, pinching little pleats to ensure a good seal.

You can tell a beautifully-filled dumpling when it can sit up on a bamboo tray on its own, like a little 3-D chubby baby learning to sit for the first time. Not enough filling, a dumpling tastes too ‘doughy.’ Too much filling, you’re in danger of leakage and a water-soaked dumpling without its savory juices is way worse than a doughy dumpling. We joke in the family how we can tell who wrapped which dumplings based on everyone’s particular style.

It’s exciting to think that we’re part of this continuum of experience and through repetition and observation, our generation will be able to carry on this part of our Shandongnese culture.

When we were kids (and during this recent Lunar New Year) we made chive dumplings with a special twist: MONEY DUMPLINGS!! Giving red envelopes to children (and adult children, ahem, ahem) is a common practice during this holiday. Mom said money dumplings are a Shandongnese tradition that takes red envelopes one-step further.

As mom wraps the dozens of dumplings, she secretly embeds a dime (don’t worry people, these dimes are disinfected before usage) inside 10 dumplings. Ten dumplings with dimes are randomly distributed among 80-100 dumplings before boiling them in water. Whoever finds a dime gets a red envelope with an unknown dollar amount.

While we never needed an additional incentive to eat more dumplings, the ‘money dumpling’ tradition adds a bit of drama and excitement to the holiday meal. Selection of dumplings that ‘look’ like they might have dimes is quite a game. No poking of dumplings with chopsticks is allowed. Whatever you put on your plate you have to eat. There are squeals of delight whenever the first family member finds a dime—there is a tense lull in eating when one family member has not found a dime yet despite eating a lot of dumplings.

Here are a few photos illustrating our Shandongnese ‘money dumpling’ food tradition during Lunar New Year 2015:

[photoshow]

Check out an audio clip of my mom talking about dumplings during her childhood and other Asian Americans sharing their Lunar New Year memories here.

Happy Year of the Ram/Goat/Sheep!

About the author: Alice Wong is a Staff Research Associate at the Community Living Policy Center at the University of California, San Francisco and a Council Member of the National Council on Disability. Follow Alice on twitter: @SFdirewolf