By Chinh Doan

(This is the latest in a series of stories leading up to the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon and the arrival of Southeast Asian refugees to the United States).

Everyone has a story. It would be impossible to share mine without the sacrifice of countless people during a long war.

April 30th, 1975: A day with a profound meaning for me every year. The date also significantly impacts millions of people, especially U.S. military men and women (current and past), their families, Vietnamese natives, and of course, Vietnamese Americans. Now, I honor the special day, the unforgettable war, by learning from my parents — listening and soaking in their stories and experiences.

AN AUDIENCE LIKE NO OTHER

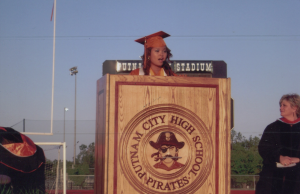

It was the audience of my dream, the one I had hope for since four years old. As I walked up to the podium, I took a deep breath and thought to myself, “You’ve already overcome your biggest struggle. Speaking in front of this crowd won’t be that difficult.” But it was. Emotions filled within me as I made eye contact with the person who made me who I am today – the woman who suffered and sacrificed so that I would one day not only go to college, but also have the opportunity to succeed beyond.

This is my big day: graduation from the University of Oklahoma with a degree in broadcast journalism and minors in international studies

This is my big day: graduation from the University of Oklahoma with a degree in broadcast journalism and minors in international studies  and Spanish. The Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication named me the “Outstanding Senior.” With that title, I led my fellow graduates in line carrying our college banner and gave the speech at convocation. And in that audience of hundreds of people: my parents – my father in his ‘American suit’ and my mother in her traditional Vietnamese dress. Our dean asked my parents to stand up as he announced my “special guest” had arrived from Vietnam just days before, just in time to be a part of my special day.

and Spanish. The Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication named me the “Outstanding Senior.” With that title, I led my fellow graduates in line carrying our college banner and gave the speech at convocation. And in that audience of hundreds of people: my parents – my father in his ‘American suit’ and my mother in her traditional Vietnamese dress. Our dean asked my parents to stand up as he announced my “special guest” had arrived from Vietnam just days before, just in time to be a part of my special day.

It was only the sixth day in America for my mother and the beginning of our new life together after nearly 18 years apart. This was also my opportunity to provide for her and give her all the necessities she had gone without for all her life.

LOSING MORE THAN THE WAR

During the last days of the Vietnam War, my mother was a homemaker, married to a South Vietnamese soldier. By this time, they had a daughter and son together. While her first husband was away at war, my mother faced many challenges on her own. She recalls the struggle to provide meals for their young family as money was tight and rice was scarce. As the war inched closer to the end, my mother was hopeful life would be better for their family. But during the Fall of Saigon, her youngest died in her arms. The one-year-old had meningitis and my mother had no options for help. Although hospitals were full of critically injured soldiers and civilians, many doctors and nurses fled. There were hardly anyone left to treat the wounded and suffering.

Even after the war, my mother did not have the opportunity to have her first husband home. By now, the North Vietnamese controlled the new government and rounded up religious leaders, employees of the old regime and former officers to “reeducation camps,” also known as communist prison.

My mother’s first husband was among these prisoners and served about three years. Following his release, he and my mother had another baby boy. Still, my mother’s first husband wanted to start a new life elsewhere that did not include her and their two surviving children. In 1978, he hopped on a boat to escape persecution and left them behind.

She later received word that the boat had sunk and the father of her children drowned. The now single mom did everything she could to care for her young daughter and son. She worked numerous jobs: went door-to-door selling fabric, sold rice at the market, worked as a typist and later became a teacher. She told me she would often stay up late grading papers by candle light and walk for miles the next day to teach.

At the same time, my father and my mom’s future second husband was also in prison, dealing with starvation, exhaustion and depression. That is also when he learned his first wife had started a new life that did not include him.

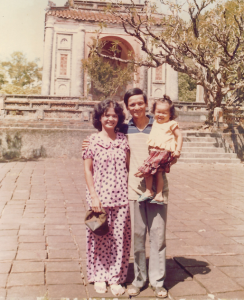

My parents did not know each other until the mid 1980s but shared similar experiences leading up to their meeting. They are both from North Vietnam, and their families fled to the southern region in the mid 1950s to escape conflict. They both lost contact with many friends and family members.

My father later became an officer in the South Vietnamese Army, and eventually he and his first wife had six kids. He served more than a decade in the military and rarely had opportunities to spend time with his family. He said he lost precious time with his children as they were growing up because he was either fighting the war or fighting to stay alive in POW camps.

After nearly ten years in prison, my father was released. He went home to his parents, who still lived in Saigon, now named Ho Chi Minh City. He was heartbroken and lonely. My father was also frustrated due to his inability to get a job since there were prejudices against anyone affiliated with the former regime.

STARTING OVER

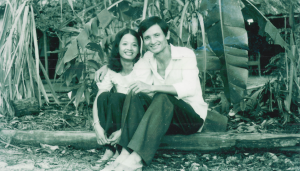

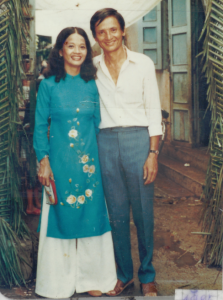

It was 1985 that my parents – a widow and divorcee – met. Their similar experiences created a strong connection, and they dated for several years. My mother was still juggling several jobs while caring for her two kids and living in rural Vietnam. My father was unemployed in the city and often visited my mother via his bicycle or a bus.

It was 1985 that my parents – a widow and divorcee – met. Their similar experiences created a strong connection, and they dated for several years. My mother was still juggling several jobs while caring for her two kids and living in rural Vietnam. My father was unemployed in the city and often visited my mother via his bicycle or a bus.

By now, my father was in his mid 40s and my mother was in her early 30s. They wanted to plan for the rest of their lives. My parents  decided to make a long-term commitment and start a family together. My mother said neighbors used to teased her that she would have a “vegetable baby” because that was all she could afford to eat while pregnant with me. Meat was too pricey and not an option for my parents. Even just days leading up to my birth, my mother labored to provide for the family. My parents eventually moved to the city to be closer to my father’s family and a hospital. About a month earlier than expected, on December 25, 1989, I was born.

decided to make a long-term commitment and start a family together. My mother said neighbors used to teased her that she would have a “vegetable baby” because that was all she could afford to eat while pregnant with me. Meat was too pricey and not an option for my parents. Even just days leading up to my birth, my mother labored to provide for the family. My parents eventually moved to the city to be closer to my father’s family and a hospital. About a month earlier than expected, on December 25, 1989, I was born.

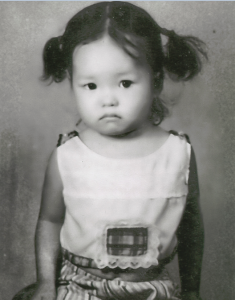

My parents said they were overjoyed for their new addition, but things were tough for our family of three. I had some health issues as a child, and we had little money to adequately care for the concerns. Our most prized possession was my father’s bicycle, used to transport all three of us: I sat in the front and would sometimes hit my heel on the front wheel. I still have scars from that, but they remind me of where I have been and the imperfect circumstances that make the rest of my journey later in life seem perfect.

Even early on in life, I knew to be grateful because I had it better than some of our other relatives, including my mother’s kids (my half-siblings) from her previous marriage. They were now teenagers with no choice but to drop out of school and start work, while living with other relatives because my parents could not provide for everyone. My mother was the breadwinner, selling rice at the market as my father took care of me. Our family moved from place to place, living in several towns. We rented homes made of mud and bamboo, even living in an attic, and eventually moved in with my grandparents. It was very crowded with nearly a dozen people in one home: our family, my grandparents, along with my father’s younger sister and her children. I enjoyed spending time with them and still hold those memories close to my heart. It was through these struggles I experienced during childhood that I learned family is most important.

Even early on in life, I knew to be grateful because I had it better than some of our other relatives, including my mother’s kids (my half-siblings) from her previous marriage. They were now teenagers with no choice but to drop out of school and start work, while living with other relatives because my parents could not provide for everyone. My mother was the breadwinner, selling rice at the market as my father took care of me. Our family moved from place to place, living in several towns. We rented homes made of mud and bamboo, even living in an attic, and eventually moved in with my grandparents. It was very crowded with nearly a dozen people in one home: our family, my grandparents, along with my father’s younger sister and her children. I enjoyed spending time with them and still hold those memories close to my heart. It was through these struggles I experienced during childhood that I learned family is most important.

LETTING GO OF HOME

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was light at the end of the tunnel, or so our family thought. The U.S. government and Vietnam reached an agreement, allowing former POWS like my father to immigrate to the United States under the “Orderly Departure Program (ODP).” Our family was thrilled for the opportunity to escape poverty and pursue the “American Dream.” When it came time to interview to see who would be qualified, my parents and me, along with my parents’ kids from their previous marriages were all hopeful. In the end, only my father and I were qualified to move to the U.S. My mother was declined because she had no proof that her first husband had died at sea — meaning her marriage to my father was not legal. Since my mother was not qualified to move to the U.S., her children were not either. My father’s children were declined because they were over the age of 18.

POWS like my father to immigrate to the United States under the “Orderly Departure Program (ODP).” Our family was thrilled for the opportunity to escape poverty and pursue the “American Dream.” When it came time to interview to see who would be qualified, my parents and me, along with my parents’ kids from their previous marriages were all hopeful. In the end, only my father and I were qualified to move to the U.S. My mother was declined because she had no proof that her first husband had died at sea — meaning her marriage to my father was not legal. Since my mother was not qualified to move to the U.S., her children were not either. My father’s children were declined because they were over the age of 18.

The situation caused our family a great deal of stress. We had some tough, life-altering decisions to make. We were torn on what to do, and either way, someone would suffer. If we were to stay in Vietnam, I would likely drop out of school before high school to work and help our family. On the bright side, we would be together and have one another’s support. If my father were to take this opportunity to bring me to America with him, then I could have a chance at a good future. However, my mother would be left in Vietnam without physical, financial and emotional support, along with the unknown of when, if ever, we would be reunited as a family.

My parents had already made many sacrifices for me, but the biggest was to come: to put their marriage on hold and split up our family for the sake of my future. The days leading up to our departure were the toughest. My mother spent extra time reading to me, brushing my hair, cooking my favorite meals, knowing it could be years before she would be able to share these simple, yet rewarding experiences with her youngest child.

My parents had already made many sacrifices for me, but the biggest was to come: to put their marriage on hold and split up our family for the sake of my future. The days leading up to our departure were the toughest. My mother spent extra time reading to me, brushing my hair, cooking my favorite meals, knowing it could be years before she would be able to share these simple, yet rewarding experiences with her youngest child.

I saw my mother many times hold back tears, just as I am doing now as I type these words and reflecting on what my parents went through. Although I was four years old, she knew I was very aware of the situation, and she did not want me to see her sad and worried. My mother stayed strong because she wanted me to believe this was the best for our family and that everything would work out.

You could not make me believe that on August 30th, 1994. The last few minutes together as a family at the airport were heart-wrenching: my parents trying their best to reassure one another that they had made the best decision for our family. Even strangers, who knew nothing about our situation, watched on with tearful eyes because they could feel the pain surrounding us as we held each other close.

My half-siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins were all there to say goodbye to my father and me and to support my mother. They knew the most difficult moments were to come following the final boarding call – when reality would sink in for my mother. And the sudden realization hit me hard. I kicked and screamed as my father pulled me away from my mother at the gate. All I could do was look back at the sliding glass door separating my mother and me as she waved back in tears. I cried non-stop for the next few hours. My father did everything he could to distract me in the mean time: buying me “Coke” (that was the only English word for soda in his vocabulary), taking me to play areas and trying to get me to fall asleep.

But I was too upset to be distracted and swayed. I refused to let go of my mother, our family and our homeland. At four years and eight months old, I did not understand why we were moving half way across the world without half of our family. Who would cook for us? Who will do my hair? What could I say when people ask me where my mom is? How I am supposed to play with the other kids when I don’t speak English? Those were just some of the many questions I asked my father on the plane ride and continuously over the next few months. I did not get answers I wanted to hear, but my father said everything would work out. I could only hope that he was eventually right.

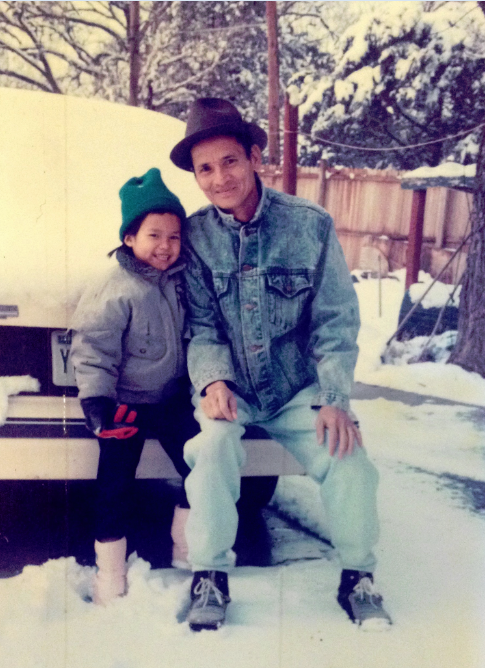

CHASING THE ‘AMERICAN DREAM’

We arrived in Oklahoma City on August 31st , that’s nearly 36 hours of travel for my first airplane experience. I spent most of it crying. Our sponsor family picked us up from the airport and allowed us to stay at their house for a few days. They then took us to rent our first apartment in Oklahoma City’s Asian District (near N.W. 23rd and Classen Blvd.). It was terrifying to be out on our own. My father, now in his mid 50s, was caring for a young girl on his own with no knowledge of the English language and hardly any money in his pocket. But we found hope and help. As refugees, we qualified for government assistance while my father went to ESL classes. We later moved to Section 8 housing in another part of Oklahoma City. There we bonded with many Vietnamese refugees like us, and we gave each other advice based on our experiences.

One of my father’s first American jobs was a janitorial position at The Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper. He brought home scraps of newspapers daily. I thought these scraps were articles he had written. I “read” them with pride. I didn’t quite know how to make sense of the words but did my best. We also watched the local news nightly before going to bed. Once the news concluded, it was time to turn the TV off and go to sleep. My love for journalism grew, as did my English comprehension.

One of my father’s first American jobs was a janitorial position at The Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper. He brought home scraps of newspapers daily. I thought these scraps were articles he had written. I “read” them with pride. I didn’t quite know how to make sense of the words but did my best. We also watched the local news nightly before going to bed. Once the news concluded, it was time to turn the TV off and go to sleep. My love for journalism grew, as did my English comprehension.

From kindergarten to transitional first grade, my first few years in school were challenging. I was nervous to speak at school and worried kids would make fun of my accent. Thankfully, I had the most incredible and loving teachers at Greenvale Elementary School. They knew my family situation and had numerous times taken me home, fed me and allowed me to play with their kids after school when my father was hard at work. They made me feel comfortable about speaking English.

Their kindness and willingness to touch lives of refugees like me, along with very encouraging and supportive ESL staff, helped me overcome the language barrier. You eventually could not get me to shut up. In fact, I loved reading, especially reading aloud in class, and raised my hand for every opportunity to have my voice heard. (I should have known then I would one day become a TV news reporter.) I know from first hand experience how a few dedicated teachers could make a big, positive difference in a child’s life.

After about two years in America, my father saved up enough money for us to make our first trip back to Vietnam. It was delightful to spend time with mom and our family, just like how I grew up, but it was difficult to leave them behind again. That was also one of the last times I would see my half-brother, the sibling closest to me. He was about 10 years older than me and babysat me when I was young.

After returning to the U.S. following our trip, a drunken motorist killed my half-brother, only his early 20s. My mother was devastated, as she had now lost two sons, while her youngest child was half a world away. Thankfully, my mother still had her eldest (my half-sister) and her husband, along with their son and daughter in Vietnam. My mother lived next door to them and enjoyed spending time with her grandkids.

In the mid 90s, our main communication to family in Vietnam was via snail mail. My mother would write us letters, we would respond, and she would receive them nearly a  month later. Then, came the international calling cards. Our conversations were short since each minute cost about a dollar, but it was great to hear the voice of our loved ones. As technology grew, so did our options of communication to Vietnam. My mother eventually went to Internet cafes and called us, costing her just a few cents per minute. When I was 10 years old, I started recording my voice, conversations, even singing on cassettes. She listened to them weekly.

month later. Then, came the international calling cards. Our conversations were short since each minute cost about a dollar, but it was great to hear the voice of our loved ones. As technology grew, so did our options of communication to Vietnam. My mother eventually went to Internet cafes and called us, costing her just a few cents per minute. When I was 10 years old, I started recording my voice, conversations, even singing on cassettes. She listened to them weekly.

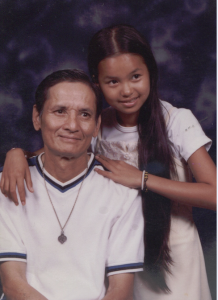

My father changed jobs a few times, later working at an air conditioning manufacturer. There was also time my father was unemployed and worked odd jobs to provide for us. Meanwhile, he was constantly dealing with back pain and other health issues caused by the harsh conditions of war and reeducation camp years earlier. Life continued to be financially challenging for my father and me, but we helped remind each other that this was in God’s plans. We got by and knew were better off than we would have been in Vietnam. I became independent early on in life and helped my father manage bills by translating information.

My father changed jobs a few times, later working at an air conditioning manufacturer. There was also time my father was unemployed and worked odd jobs to provide for us. Meanwhile, he was constantly dealing with back pain and other health issues caused by the harsh conditions of war and reeducation camp years earlier. Life continued to be financially challenging for my father and me, but we helped remind each other that this was in God’s plans. We got by and knew were better off than we would have been in Vietnam. I became independent early on in life and helped my father manage bills by translating information.

At a young age, I knew our family would not be able to pay for my college. Throughout middle school and high school, I worked hard on my academics and was determined to make my parents proud. I graduated middle school with a 4.0 and participated in the district’s “gifted student program.” In high school, I took on leadership roles on the volleyball and tennis teams and became Student Council president my senior year. I gave a speech representing the student body at graduation in May of 2008. That moment instilled in me the need to bring my mother over in time for my next big moment: college graduation.

In the summer of 2008, I became a naturalized citizen and even acquired an English middle name, “Theresa,” for my patron saint, Saint Theresa the Little Flower. The process, the ceremony, the feeling that the American dream still exists, all make up one of the most thrilling moments of my life. My father was there to witness my oath of allegiance to our new country. He was proud and hopeful I would be the answer to bringing my mother to America.

A few months later, I started my freshman year as an American citizen at the University of Oklahoma with my mind set on becoming a TV journalist. I was fortunate enough to receive numerous scholarships and financial aid. I managed to fit in extracurricular activities from Greek life, to faith-based organizations, to the nightly student-produced newscast. I had multiple internships at local news stations, along with NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder and the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum. One of my fondest memories was spending a summer in New York City at the Today Show through the Asian American Journalists Association/NBCUniversal Fellowship. During my college years, I also worked several part-time jobs to save money for the goal I have had since I was four years old: reuniting our family.

THE RACE AGAINST TIME

When I turned 21, the minimum age to sponsor a family member, I hired an attorney from Catholic Charities and applied for the I-130 (the petition for an alien relative).

The next step was more challenging: my mother was required to go to every town she ever lived in and gather certain documents for the application. With the help of her eldest by her side, my mother traveled throughout Vietnam during monsoon season to get the necessary documentation notarized. It was a race against time: dealing with the weather, a difficult Communist government (we had to be very patient in order to get documents belonging to us) and the challenges of gathering paperwork that were lost during the Vietnam War.

Meanwhile, I fundraised to save money for attorney fees and flights. Through my creativity, love for fashion and entrepreneurial spirit, I started a business called “Sisters Before  Misters,” making hair accessories and home décor to sell around OU campus and at different Greek philanthropic events. I barely slept during college. I spent most of my time studying, working, getting involved in campus organizations and producing items to sell for my business.

Misters,” making hair accessories and home décor to sell around OU campus and at different Greek philanthropic events. I barely slept during college. I spent most of my time studying, working, getting involved in campus organizations and producing items to sell for my business.

One of the biggest obstacles for me was the financial assets required to sponsor. Through my part-time jobs and small business, I was able to save a few thousand dollars. That was not enough to meet the financial requirement. I continued praying. A Tri Delta alumna, Marylee, stepped in and told me, “I refuse for you to not let me help. My husband and I are not rich or anything, but we should be able to meet the requirements to be your co-sponsor.” Thanks to her generous offer, that step of my application was approved.

We were very excited when my mother had gathered all the documents in February 2012, but then we met challenges with my attorney. The lawyer at Catholic Charities was too overworked to see me, and I was working against the clock since I wanted to get my mother over in time for graduation in May. She suggested I find another attorney who could put in the time and effort needed to expedite the application. I contacted several attorneys, and many said it was very unlikely that my mother would make it over in time for my graduation, and it would cost a lot more than I could afford.

Once again, I sought guidance through my faith. I prayed that I would find an attorney who also had faith and the work ethic needed to make my dream a reality. The next day, I found an attorney named Kate, who lived in Norman (near my college campus), did work on the side for Catholic Charities and was willing to come to the place of my internship to get the application moving immediately. Kate was one of the many answers to my prayers, a joy to work with and very encouraging. Still, I felt that there was something else I needed to do in order to make sure my mother would be present at my graduation.

Some of my mentors suggested I seek help from my university president, David Boren, and connect with Oklahoma leaders. I contacted President Boren and told him about my goal and current status. He immediately called his son, Congressman Dan Boren, in Washington, DC. Congressman Boren’s office communicated with me, and I gave them all the information I knew. I even went to our nation’s capital to meet with Congressman Boren. His office helped speed up my mother’s application, and she received notice that she would have an interview in late April.

Because my mother’s interview date was cutting too close to my graduation date, I asked President Boren and Congressman Boren to help me petition for an “emergency expedited processing.” We were told this would be difficult because that is often reserved for a medical emergency. We still did our best to present reasons why my mother’s case needed extra care: we sent a graduation announcement, my personal statement and letters from President Boren and Congressman Boren.

Both of the Borens were very helpful in expediting my case, and my mother was able to get an interview earlier than her previous appointment. Immediately after her interview, my mother found out she passed all requirements, and she received her permanent Visa about a week later.

My mother had never flown before, and she requested that I travel to Vietnam and help her make the big move. I also knew it would be difficult for my mother to say goodbye to her oldest daughter, grandchildren, siblings and so many family members and friends, and I was more than willing to be of support for her. I had a lot to figure out: how to pay for my mother’s ticket AND mine and miss school during such a crucial time.

My mother had never flown before, and she requested that I travel to Vietnam and help her make the big move. I also knew it would be difficult for my mother to say goodbye to her oldest daughter, grandchildren, siblings and so many family members and friends, and I was more than willing to be of support for her. I had a lot to figure out: how to pay for my mother’s ticket AND mine and miss school during such a crucial time.

Before my mother’s big move, I returned to Vietnam to visit our family five times total – 1996, 1998, 1999, 2007, 2009. But this time would be my sixth and hopefully the last time I would need to travel overseas to visit my mother.

Once again, I witnessed the power of faith. My friends found out about my news and wanted to help. I received a few donation checks here and there to help pay for the plane tickets, along with many prayers and encouraging words. My professors allowed me to miss one week of class and make up anything everything else. Several people wanted to donate old furniture and clothes to my mother and help her find a job. I even received donations of used clothes to take to my family members in Vietnam.

Once landing in Vietnam, my mother, half-sister, aunts, uncles and cousins — the same people who were there to send my father and I off to American nearly 18 years ago were back to support. We all hopped in a rental caravan and immediately headed to my mother’s home in Long An, a rural part of south Vietnam, to help my mother pack. How was my mother going to pack 57 years worth of her life in Vietnam in two suitcases ?

She left most of her belongings – including a washer, refrigerator, TV, rice cooker and other electronics I bought her to help her live a better life – to my half-sister. She and her family had none of these things, and they were grateful. My mother, however, packed the most important possessions she owned: the spoon she used to feed me as a baby, my traditional Vietnamese dress from my toddler years, numerous albums of photos of our family (both together and half a world apart) and other items she considered irreplaceable.

My mother gave everything else to her surviving brother and sister. She grew up extremely close to her four siblings. Their mother died when she was only six years old, and their father remarried and had kids with his new wife. My mother and her siblings were left to care for one another. Although none of them ever had much, they always looked out for each other. My mother was now the eldest still alive. They had already lost two brothers to health problems, and now their big sister was to move to a new country, not knowing when she would be able to see them again.

Just after three days in Vietnam, it was time to head back to the airport. Although my mother always knew in her heart she wanted to be with her youngest daughter in America, she anticipated when the day came for her big move, it would be painful to say goodbye to her eldest and her two grandchildren. I went experienced similar emotions as August 30, 1994, while watching my mother hug my half-sister and her grandchildren. Then it was time to walk through that sliding glass door and wave back at our family as we all cried.

My mother was nervous for her first flight, but she said she felt much better having me by her side to guide and advise. It was unreal to open my eyes after a nap mid-flight and see my mother next to me, as we were thousands of miles in the air. This was it: the beginning of the rest of our lives.

MY VERSION OF ‘HAPPILY EVER AFTER’

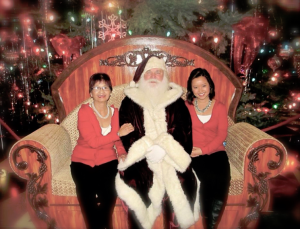

After 18 years of living apart, due to my diligence and the many people who helped me, I brought my mother to Oklahoma City the Monday of my

After 18 years of living apart, due to my diligence and the many people who helped me, I brought my mother to Oklahoma City the Monday of my  graduation week. Our final flight was delayed a few hours. Still, on a late Monday night, my mother and I walked arm-in-arm into an airport lobby surrounded by my father, childhood friends, sorority sisters, college professors and mentors – all whom contributed to making this day possible.

graduation week. Our final flight was delayed a few hours. Still, on a late Monday night, my mother and I walked arm-in-arm into an airport lobby surrounded by my father, childhood friends, sorority sisters, college professors and mentors – all whom contributed to making this day possible.

Here is the link to a TV news story by fellow Asian American Journalist Association member Priscilla Luong:

Straight from Will Rogers Airport, we headed to Norman, where my mother would experience Greek life while staying in the gigantic sorority house, my home for the last three years of college. I studied for my finals and finished up coursework as my mother was getting used to her new American life. It was the most overwhelming but exciting week of my life thus far: showing my parents around campus, introducing them to my friends and mentors and finalizing my convocation speech.

Straight from Will Rogers Airport, we headed to Norman, where my mother would experience Greek life while staying in the gigantic sorority house, my home for the last three years of college. I studied for my finals and finished up coursework as my mother was getting used to her new American life. It was the most overwhelming but exciting week of my life thus far: showing my parents around campus, introducing them to my friends and mentors and finalizing my convocation speech.

Following graduation, I went back to New York City for the summer, an all-expense paid fellowship through the International Radio & Television Society. I was assigned to CBS News and had an incredible experience learning from industry professionals and getting to know other fellows, whom I still stay in touch with on a regular basis.

After that NYC adventure, I packed up my belongings in Oklahoma City and headed for Central Texas to be a reporter. Our family decided my mother should go with me so we could make up for loss time. Also since I was a young woman, having my mother with me would make my parents feel better. My father stayed in Oklahoma City due to health reasons. His doctors are all there. Plus, three of his daughters (my half-sisters) from his previous marriage eventually immigrated to Oklahoma as adults and are able to help care for him.

Thanks to wonderful friends, even strangers who did not know my family but heard about our story, donations for our first home poured in. We received new and gently used furniture, home décor, and dishes, even gift cards so that my mother and I could buy necessities.

Our time in Texas was wonderful. I became close with my co-workers, members of the young professionals group and the military community. My mother had an amazing tutor, who became more of a friend to us. We also met fellow Vietnamese Americans and often had dinner at their homes. It was a tough decision, but after about a year in Texas, we packed up and moved to Nebraska for my next reporting opportunity.

Our time in Texas was wonderful. I became close with my co-workers, members of the young professionals group and the military community. My mother had an amazing tutor, who became more of a friend to us. We also met fellow Vietnamese Americans and often had dinner at their homes. It was a tough decision, but after about a year in Texas, we packed up and moved to Nebraska for my next reporting opportunity.

Before my interview, I had never been to Nebraska, but Omaha turned out to be a ‘hidden gem’ and now our home. The people and culture are what make this city so likable. From my coworkers, to people I meet on stories daily, everyone is welcoming, helpful and kind. My mother and I became involved with the Vietnamese American community here. I emceed the 20th anniversary of Omaha’s Vietnamese Lunar New Year festival. We also found another fantastic and very loving tutor for my mother. She is patient, smart and encouraging. I can talk about Omaha for days.

May 7th marks my mother’s third anniversary as a U.S. resident. She has lived in three states and visited two others. She hopes to become a naturalized citizen like me in two years, when she meets the qualifications. I am extremely proud of her willingness to adapt and learn. My mother enjoys American food – anything from the ‘typical’ hamburger and pizza to peanut butter-filled pretzels and cheeses. She continues to amaze me with her love for life after many difficult years. My mother and I are learning and growing together: She teaches me to cook Vietnamese and also helps me to improve my Vietnamese language skills, while I teach her the English language and American culture and customs.

Sure, it’s not the happily ever after I would have imagined as a young girl, but we are happy and beyond grateful. We are together in the same country. Plus, we can communicate with my father any time (no long distance costs!), and we are blessed to live in a free country.

THE JOURNEY AHEAD

We have no idea what is next in this crazy life journey, but we have each other. We often joke about how if we could make it through the past two decades, we could survive many more.

We have no idea what is next in this crazy life journey, but we have each other. We often joke about how if we could make it through the past two decades, we could survive many more.

People often say to me, “It’s amazing how much you know about your history and how much you remember from your childhood.” I  am constantly learning about my history because it is a part of me, and I am a part of it. It has made me who I am today. Growing up, one of the few constants I had in life was the memory of my childhood in Vietnam. I held on to every moment, everything I could possibly remember because I did not know whether I would get to return to my homeland, whether I would ever get to live with my mother again.

am constantly learning about my history because it is a part of me, and I am a part of it. It has made me who I am today. Growing up, one of the few constants I had in life was the memory of my childhood in Vietnam. I held on to every moment, everything I could possibly remember because I did not know whether I would get to return to my homeland, whether I would ever get to live with my mother again.

Having lived just 25 years, God has brought many incredible people into my life: community leaders, mother and father figures, people who loved me just like family. All these people helped me reach my goal. I can only hope to give back to others in some way – whether that’s through an act of kindness, being a good role model to aspiring journalists or living my life as a reminder that the American Dream exists and will continue to thrive if we all continue to believe in it.

family. All these people helped me reach my goal. I can only hope to give back to others in some way – whether that’s through an act of kindness, being a good role model to aspiring journalists or living my life as a reminder that the American Dream exists and will continue to thrive if we all continue to believe in it.

RELATED STORIES

Child Learns Lessons of War & Survival

Death-defying Journey to Freedom After the Fall of Saigon

Ken Kashiwahara Returns 40 Years Later to Recall the Fall of Saigon