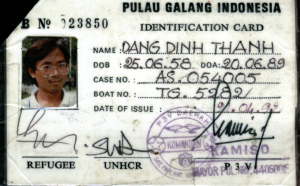

(This is the latest in a series of stories on AsAmNews to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon and the arrival of Southeast Asian refugees to the United States. The following is a question and answer with Thanh Dang. His story is featured in the book Boat People: Personal Stories From the Vietnamese Exodus by Carina Hoang which is available on Amazon.)

By Jason Fong

1. What struggles did you encounter in your journey for asylum in Indonesia?

During the trip, we had gone through bad weather and shortage of food and water . We tried to collect rain water, but it was too salty to drink . We were intercepted by pirates, who robbed us of the little valuable things we had left, but fortunately, they did not rape or take any women on board.

But the hardest part for me was not knowing where we were in the middle of the ocean, and when our trip would end. Once we got into the international sea-lane, we met many cargo ships passing by, and none of them stopped to help us. There was a Taiwanese ship that came so close that we thought they would see our suffering and pick us up, but the crew looked at us curiously, took some pictures and kept going . After that, I was miserably disappointed.

2.What was the interview process like once you arrived in Indonesia?

The screening process was conducted in two phases. At first, I was interviewed by local officials who reviewed my background based on the bio history filled out when I first arrived at the camp. Also, the interviewer asked for details of the trip, and most important, the reasons that I had to leave Vietnam, as well as the proof. The second interview was run by a UNCR (United Nation Command Rear)officer with the participation of the local authorities , and NGO (Non-government official)representatives. They asked many detailed questions based on the information they had obtained from the first interview. The goal was to dig deep into any holes that they found in my testimonies to prove that I had no case to become a political refugee. In my case, knowing that I was trained as an architect, the UN lawyer gave me his advice with a straight face that I should go back to Vietnam because the country was changing and it needed people in my profession to build it up . He did not care what I had to say in that I would not be able to practice my profession because of what I had done.

3. Do you see your own experience as similar towards that of other refugees?(how so/not, in what ways)

Like the other “boat people”, we shared the common suffering of our journey: the bad weather, the starvation, the lack of water and even the encounter with pirates. But we were lucky in a sense that no one was harmed or killed on our trip. However, for the people on our boat, our hardship did not end when we got onshore. We were transported from one place to the other, and had to wait for a month in horrible living conditions before arriving to Galang Refugee camp. The screening process created other difficulties that I felt were even worse than the sea journey .

4. Why did you leave Vietnam/seek asylum?

4. Why did you leave Vietnam/seek asylum?

There was a saying Southerners often said after the 4/30 event: if the street lamps had legs, they would also leave. As a young person lucky enough to receive a college education after the war was over, I was a bit naive, and was completely idealistic in believing in Vietnam’s future as a united country. I had turned down many offers to escape from my own family during my years in college, even when I did not qualify to be a member of HCM Communist Youth Union, which is a requisite for getting into the Communist Party, due to my background and upbringing.

After graduating, I went to work for a government agency in a small city, and had an opportunity to participate in an operation where the local authority confiscated properties of a family of a former South Vietnam officer to transfer to a state own company that paid them handsomely. I could not stand witnessing the family with old and young women being forcefully evicted – literally being thrown out onto the street with their meager belongings. I spoke out against it, and quit on the spot. My actions were considered “intolerable” by the government and the agency, which had earned me a “self-confession session”, and left a black mark in my biography history and ruined my career. Knowing that I would have no future in this profession, and realizing the real cores of the regime I was serving, I made my decision to get out of the country as soon as I could .

RELATED STORIES

How a 10-Year-Old Survived the Fall of Saigon & Made It to The US

Fall of Saigon: 40 Years Later Through the Eyes of A Vietnamese American

Child Learns Lessons of War & Survival

Death-defying Journey to Freedom After the Fall of Saigon

Ken Kashiwahara Returns 40 Years Later to Recall the Fall of Saigon