By Lia Chang

AsAmNews Arts & Entertainment Reporter

China: Through the Looking Glass at The Metropolitan Museum of Art has been extended by three weeks through Labor Day, September 7th. The exhibition, organized by The Costume Institute in collaboration with the Department of Asian Art, opened to the public on May 7th, and as of July 31st, has drawn more than 500,000 visitors according to WWD.com.

Encompassing approximately 30,000 square feet in 16 separate galleries in the Museum’s Chinese and Egyptian Galleries and Anna Wintour Costume Center, it is The Costume Institute’s largest special exhibition ever, and also one of the Museum’s largest. With gallery space three times the size of a typical Costume Institute major spring show, China has accommodated large numbers of visitors without lines.

“This exhibition is one of the most ambitious ever mounted by the Met, and I want as many people as possible to be able see it,” said Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Met. “It is a show that represents an extraordinary collaboration across the Museum, resulting in a fantastic exploration of China’s impact on creativity over centuries.

To date, the exhibition’s attendance is pacing close to that of Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (2011), which was the most visited Costume Institute exhibition ever, as well as the Met’s eighth most popular.

The exhibition explores the impact of Chinese aesthetics on Western fashion and how China has fueled the fashionable imagination for centuries. High fashion is juxtaposed with Chinese costumes, paintings, porcelains, and other art, including films, to reveal enchanting reflections of Chinese imagery. The exhibition, which was originally set to close on August 16, is curated by Andrew Bolton. Wong Kar Wai is artistic director and Nathan Crowley served as production designer.

Below are excerpts from Wong Kar-Wai’s speech.

“Putting together this show has been a truly remarkable journey for myself and everyone involved. Our creative team was comprised of experts across various disciplines including fine arts, fashion and cinema. Together we hope to offer you a collective perspective that is both compelling and provocative.

One of the most fascinating parts of this journey for myself was having the opportunity to revisit the Western perspective of the East through the lens of early Hollywood. Whether it was Fred Astaire playing a fan dancing Chinese man or Anna May Wong in one of her signature Dragon Lady roles, it is safe to say that most of the depictions were far from authentic.

Unlike their filmmaking contemporaries, the fashion designers and tastemakers of that period take those distortions as their inspiration and went on to create a Western aesthetic with new layers of meanings that was uniquely their own.

In this exhibition, we did not shy away from these images because they are historical fact in their own reality. Instead, we look for the areas of commonality and appreciate the beauty that abounds.

With China: Through the Looking Glass, we have tried our best to encapsulate over a century of cultural interplay between the East and West that has equally inspired and informed. It is a celebration of fashion, cinema and creative liberty. It is an important time in the human history for cross cultural dialogue and I’m proud and delighted to contribute to the conversation.”

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871), the heroine enters an imaginary, alternative universe by climbing through a mirror in her house. In this world, a reflected version of her home, everything is topsy-turvy and back-to-front. Like Alice’s make-believe world, the China mirrored in the fashions in this exhibition is wrapped in invention and imagination.

“From the earliest period of European contact with China in the 16th century, the West has been enchanted with enigmatic objects and imagery from the East, providing inspiration for fashion designers from Paul Poiret to Yves Saint Laurent, whose fashions are infused at every turn with romance, nostalgia, and make believe,” said Andrew Bolton, Curator in The Costume Institute. “Through the looking glass of fashion, designers conjoin disparate stylistic references into a fantastic pastiche of Chinese aesthetic and cultural traditions.”

Designers featured in China: Through the Looking Glass include Cristobal Balenciaga, Bulgari, Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen, Callot Soeurs, Cartier, Roberto Cavalli, Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, Tom Ford for Yves Saint Laurent, John Galliano for Christian Dior, Jean Paul Gaultier, Valentino Garavani, Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Picciolo for Valentino, Craig Green, Guo Pei, Marc Jacobs for Louis Vuitton, Charles James, Mary Katrantzou, Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel, Jeanne Lanvin, Ralph Lauren, Judith Leiber, Christian Louboutin, Ma Ke, Mainbocher, Martin Margiela, Alexander McQueen, Alexander McQueen for Givenchy, Edward Molyneux, Kate and Laura Mulleavy, Dries van Noten, Jean Patou, Paul Poiret, Yves Saint Laurent, Paul Smith, Vivienne Tam, Isabel Toledo, Giambattista Valli, Vivienne Westwood, Jason Wu, and Laurence Xu.

The Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery

Emperor to Citizen

There are a series of “mirrored reflections” through time and space, focusing on the Qing dynasty of Imperial China (1644-1911); the Republic of China, especially Shanghai in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s; and the People’s Republic of China (1949-present) in The Anna Wintour Costume Center’s Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery. These reflections, as well as others in the exhibition, have been illustrated with scenes from films by such groundbreaking Chinese directors as Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Ang Lee, and Wong Kar-Wai, artistic director of the exhibition. Several of the galleries also feature original compositions by internationally acclaimed musician Wu Tong.

Upon entering the Costume Institute galleries, there’s a video tunnel showing Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor, a broad and sweeping journey of Chinese history, and at the end of the tunnel is a festival robe worn by the last emperor, Pu Yi, when he was four years old.

Yellow silk satin embroidered with polychrome silk and metallic thread Courtesy of The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Western designers have been inspired by China’s long and rich history, with the Manchu robe, the modern qipao, and the Zhongshan suit (after Sun Yat-sen, but more commonly known in the West as the Mao suit, after Mao Zedong), serving as a kind of shorthand for China and the shifting social and political identities of its peoples, and also as sartorial symbols that allow Western designers to contemplate the idea of a radically different society from their own.

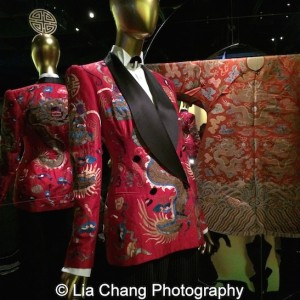

Tom Ford for Yves Saint Laurent Evening dress of red silk satin embroidered with polychrome plastic sequins; gray fox fur Gift of Yves Saint Laurent, 2005.

Manchu Robe

In terms of the Manchu robe, Western designers usually focus their creative impulses toward the formal (official) and semiformal (festive) costumes of the imperial court in all of their imagistic splendor and richness. Bats, clouds, ocean waves, mountain peaks, and in particular, dragons are presented as meditations on the spectacle of imperial authority. Most of the robes in this gallery—several of which belong to the Palace Museum in Beijing—were worn by Chinese emperors, a fact indicated by the twelve imperial symbols woven into or embroidered onto their designs to highlight the rulers’ virtues and abilities: sun with three-legged bird; moon with a ”jade hare” grinding medicine; constellation of three stars, which, like the sun and moon, signify enlightenment; mountains to signify grace and stability; axe to signify determination; Fu symbol (two bow-shaped signs) to signify collaboration; pair of ascending and descending dragons to signify adaptability; pheasant to symbolize literary elegance; pair of sacrificial vessels painted with a tiger and a long-tailed monkey to signify courage and wisdom; waterweed to signify flexibility; flame to signify righteousness; and grain to signify fertility and prosperity.

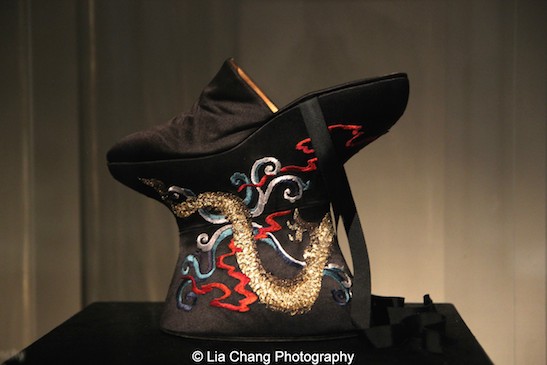

In a surrealist act of displacement, the British milliner Stephen Jones, commissioned by the museum to create the headpieces in the exhibition, has relocated these symbols, whose placement on the imperial costumes of the emperor was governed by strict rules, to the head, where they appear as three-dimensional sculptural forms.

The Carl and Iris Barrel Apfel Gallery

Traditional and haute couture qipaos as interpreted by Western designers are on display in The Carl and Iris Barrel Apfel Gallery along with film clips from Wong Kar Wai’s The Hand from Eros, 2004 and In the Mood for Love, 2000; The Goddess, a 1934 film directed by Wu Yonggang; Lust, Caution, 2007 directed by Ang Lee; The World of Suzie Wong, 1960 directed by Richard Quine.

In the period between the two world wars, film actresses in Shanghai, known as the Hollywood of the East, were in the vanguard of fashion. Through their images on screen as well as in lifestyle magazines, they led new trends in the modern qipao. In the 1930s, the most eminent actress was Hu Die (Butterfly Wu), whose qipaos are on view.

Elected the Queen of Cinema after a nationwide poll by the Star Daily newspaper in 1933, she won favor with her on-screen depictions of virtuous women and her off-screen persona of ladylike sophistication. In the West, Hu Die became an embodiment of Chinese femininity. Her photograph appeared in a 1929 issue of American Vogue as the example of modern “Chinese elegance.”

Over time, the silhouette of the qipao evolved, quoting Western, specifically Parisian and Hollywood, aesthetics. Its columnar, body-skimming silhouette of the 1920s, a narrower expression of the flapper’s chemise, became a contour-cleaving fit in the 1930s, similar to the haut monde’s and screen sirens’ glamorous bias-cut gowns.

From the 1920s to the 1940s, the modern qipao was considered a form of national dress in China. An aristocratic version was promoted during this period by images of Oei Hui- Ian, the third wife of the Chinese diplomat and politician Vi Kuiyuin Wellington Koo, and Soong Mei-ling, the wife of Chiang Kai-shek, a military and political leader and eventual president of the Republic of China.

While the qipao became the signature style of both women, who were known in the West for their sophistication, Oei Hui-Ian was also a couture client and would often mix her qipaos with jackets by Chanel and Schiaparelli. A 1943 issue of American Vogue features a Horst photograph of Oei Hui-Ian wearing the version on view here, which is embroidered with the traditional motif of one hundred children. The article in the same issue describes her as “a Chinese citizen of the world, an international beauty.”

The modern qipao is a favorite of Western designers, not only because of its allure and glamour but also because of its mutability and malleability, and it can be rendered in any print, fabric, or texture, conveying whatever desires and associations they stimulate in the minds of designers.

Egyptian Art Landing

In the Egyptian Art Landing, film clips of Chung Kuo: Cina (1972) directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, In the Heat of the Sun (1994) directed by Jiang Wen, and The Red Detachment of Women (1970) directed by Fu Jie and Pan Wenzhan play on the screens above the garments on display. The Zhongshan suit, or Mao suit as it is more commonly known in the West, remains a powerful sartorial signifier of China, despite the fact that it began disappearing from the wardrobes of most Chinese men and women, aside from government officials, in the early 1990s. For many Western designers, the appeal of the Mao suit rests in its principled practicality and functionalism.

Its uniformity implies an idealism and utopianism reflected in its seemingly liberating obfuscation of class and gender distinctions. During the late 1960s, a time of international political and cultural upheaval, the Mao suit in the West became a symbol of an anti- capitalist proletariat. In Europe, it was embraced enthusiastically by the left-leaning intelligentsia specifically for a countercultural and antiestablishment effect.

For Tseng Kwong Chi, who was born in Hong Kong and active in the East Village in the 1980s, the Mao suit was a vehicle to explore Western stereotypes of China. From his self- portrait series East Meets West (also known as the Expeditionary Series, 1979-90), he masqueraded as a visiting Chinese dignitary wearing mirrored sunglasses and a Mao suit, and stood in front of various cultural and architectural landmarks and natural landscapes. Exploiting the fact that people treated him differently based on his dress, the artist used his adopted persona, which he described as an “ambiguous ambassador,” to illustrate the West’s naïveté and ignorance of the East. The catalyst for East Meets West was President Richard M. Nixon’s trip to China in 1972, an event that the artist defined as “a real exchange [that] was supposed to take place between the East and West. However, the relations remained official and superficial.

The art of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) profoundly influenced the American and European avant-garde. Andy Warhol created his first screen-printed paintings of Mao Zedong in 1973, immediately following President Richard M. Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, and over time made nearly two thousand portraits in various sizes and styles. Both model and multiple, Warhol’s Mao is undeniably of the masses, like the original 1964 portrait that was reproduced in the millions as the frontispiece to the Little Red Book.

In his Chairman Mao series (1989), Zhang Hongtu, who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, extended a Warholian sensibility to his own mode of Political Pop, lending a satirical eye to the 1964 portrait. For her spring/ summer 1995 collection, designer Vivienne Tam, who was born in Guangzhou, collaborated with Zhang to create a dress printed with images from the Chairman Mao series. The same collection also included a silk jacquard suit of the 1964 portrait.

In China: Through the Looking Glass, the Astor Forecourt gallery has been devoted to Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong. Haute Couture designs by Yves Saint Laurent, Ralph Lauren, Paul Smith and John Galliano for the House of Dior inspired by Ms. Wong, are displayed alongside a Travis Banton gown she wore in Limehouse Blues(1934). Ms. Wong can be seen in a montage of rare film clips edited by Wong Kar-Wai, vintage film stills and photographs by Edward Sheriff Curtis and Nickolas Muray.

In terms of shaping Western fantasies of China, no figure has had a greater impact on fashion than Ms. Wong. Born in Los Angeles in 1905 as Huang Liushuang (”yellow willow frost”), she was fated to play opposing stereotypes of the Enigmatic Oriental, namely the docile, obedient, submissive Lotus Flower and the wily, predatory, calculating Dragon Lady.

Film clips featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong include Daughter of the Dragon, 1931 Directed by Lloyd Corrigan (Paramount Pictures, Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC); Limehouse Blues (1934) directed by Alexander Hall (Paramount Pictures UCLA Film & Television Archive); Piccadilly (1929) directed by E. A. Dupont (British International Pictures, Courtesy of Milestone Film & Video and British Film Institute); Shanghai Express, (1932) directed by Josef von Sternberg (Paramount Pictures, Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC); and The Toll of the Sea (1922) directed by Chester M. Franklin (Metro Pictures Corporation, UCLA Film & Television Archive) run on overhead screens in The Astor Forecourt.

Limited by race and social norms in America and constrained by one- dimensional caricatures in Hollywood, she moved to Europe, where the artistic avant-garde embraced her as a symbol of modernity. The artists Marianne Brandt and Edward Steichen found a muse in Anna May Wong, as did the theorist Walter Benjamin, who in a 1928 essay describes her in a richly evocative manner: “May Wong the name sounds colorfully margined, packed like marrow-bone yet light like tiny sticks that unfold to become a moon-filled, fragranceless blossom in a cup of tea,” Benjamin, like the designers in this gallery, enwraps Anna May Wong in Western allusions and associations, In so doing, he unearths latent empathies between the two cultures, which the fashions on display here extend through their creative liberties.

Gallery- Astor Garden

The exhibition’s subtitle “Through the Looking Glass” translates into Chinese as “Moon in the Water,” that alludes to Buddhism. In the Met’s Astor Chinese Garden Court, a moon was projected onto the ceiling and reflected in what appears to be a shallow pool. Dresses by John Galliano and Martin Margiela—which appear like apparitions on the water—were inspired by Beijing opera.

Like “Flower in the Mirror,” it suggests something that cannot be grasped, and has both positive and negative connotations. When used to describe a beautiful object, “moon in the water” can refer to a quality of perfection that is either so elusive and mysterious that the item becomes transcendent or so illusory and deceptive that it becomes untrustworthy.

The metaphor often expresses romantic longing, as the eleventh-century poet Huang Tingjian wrote: “Like picking a blossom in a mirror/Or grabbing at the moon in water/I stare at you but cannot get near you.” It also conveys unrequited love, as in the song “Hope Betrayed” in Cao Xueqin’s mid-eighteenth-century novel Dream of the Red Chamber: “In vain were all her sighs and tears/In vain were all his anxious fears:/As moonlight mirrored in the water/Or flowers reflected in a glass.”

Two other garments by Maison Martin Margiela are recycled opera costumes from the 1930s that have been repurposed as haute couture, an extraordinarily East-meets-West display of technical virtuosity.

Gallery Ming Furniture Room

Film clips of Raise the Red Lantern (1991) directed by Zhang Yimou, Farewell My Concubine (1993) directed by Chen Kaige, Mei Lanfang’s Stage Art (1955) and Two Stage Sisters (1964) directed by Xie Jin serve as a vivid backdrop to the designs on display in the Ming Furniture Room.

In Chinese culture, the color red, which traditionally corresponds to the element of fire, symbolizes good fortune and happiness. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, red also came to represent the communist revolution. In the West, the color is so strongly associated with China that it has come to stand in for the nation and its peoples. When Valentino presented its Manifesto collection in Shanghai in 2013, the creative directors Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli dedicated it to “the many shades of red.” In choosing the color as the theme, they were also referencing the history of Valentino, as red has long been a signature color of the house. As early as the 1960s, its founder, Valentino Garavani, employed it throughout his collection, especially in his lavish evening designs. In this gallery are several gowns from the Manifesto collection, which epitomize the atelier’s exquisite lacework and meticulous and magnificent embroideries.

Gallery: Export Silk

Ever since the silk trade between China and the Roman Empire blossomed in the late first and early second centuries, Western fashion’s appetite for Chinese silk textiles has been insatiable. This craving intensified in the sixteenth century, when sea trade expanded the availability of Chinese luxury goods, giving rise in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to a lasting taste for chinoiserie.

Chinese export silks, like export wallpapers, have sometimes been subsumed into the history of the applied arts in the West. Yet despite their Western-inspired decoration, they remain part of the history of the material culture of China, particularly the port city of Canton (now Guangzhou). The relationship between producer and consumer, however, is complicated by the transmission of design elements between East and West. Like the sinuous motifs on the painted silks and wallpapers in these galleries, Chinese export art reveals multiple meanderings of influence from the earliest period of European contact with China, leading to the accumulation of layers and layers of stylistic translations and mistranslations.

Gallery – Calligraphy

Western fashion’s abiding interest in Chinese aesthetics embraces the graphic language of calligraphy, which in China is considered the highest form of artistic expression. Designers are typically inspired by calligraphy for its decorative possibilities rather than its linguistic significance. Chinese characters serve as the textile patterns on the dresses by Christian Dior and Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel in this gallery.

Because this language is seen as “exotic” or “foreign,” it can be read as purely allusive decoration. Dior and Chanel were likely unaware of the semantic value of the words on their dresses, which in the case of Dior has resulted in a surprising and humorous juxtaposition. The dress is adorned with characters from an eighth- century letter by Zhang Xu in which the author complains about a painful stomachache. Language that constitutes communication, it would seem, is also capable of conveying miscommunication. Here, the letter is presented as a rubbing, as are the other calligraphic examples in the surrounding cases. Before photography, rubbings were the key technology for transmitting calligraphy across generations. Some of the greatest treasures of Chinese calligraphy, including the Letter on a Stomachache that inspired Dior, survive only through such impressions.

Frances Young Tang Gallery – Blue and White Porcelain

The story of blue-and-white porcelain encapsulates centuries of cultural exchange between East and West. Developed in Jingdezhen during the Yuan dynasty (1271– 1368), blue-and-white porcelain was exported to Europe as early as the sixteenth century.

As its popularity increased in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in tandem with a growing taste for chinoiserie, potters in the Netherlands (Delft), Germany (Meissen), and England (Worcester) began to produce their own imitations.

One of the most familiar examples is the Willow pattern, which usually depicts a landscape centered on a willow tree flanked by a large pagoda and a small bridge with three figures carrying various accoutrements. Made famous by the English potter Thomas Minton, founder of Thomas Minton & Sons in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, it was eventually mass- produced in Europe using the transfer-printing process.

With the popularity of Willow-pattern porcelain, Chinese craftsmen began to produce their own hand-painted versions for export. Thus a design that came to be seen as typically Chinese was actually the product of various cultural exchanges between East and West.

Gallery – Perfume

Part of the power of perfume lies in its synesthetic possibilities, and the idea of China, confected from Western imagination, affords the perfumer a multiplicity of olfactory opportunities charged with the seductive mysteries of the East. Paul Poiret, famous for his fashions a la chinoise, was the first designer to produce a perfume fueled by the romance of China. Called Nuit de Chine, it was created in 1913 by Maurice Schaller and presented in a flacon inspired by Chinese snuff bottles designed by Georges Lepape, In the early 1920s, Poiret, excited by his dreams of Cathay, crafted several other perfumes, including orient and Sakya Mouni, both packaged in bottles inspired by Chinese seals.

The 1910s and 1920s saw an influx of China-inflected perfumes, partly stimulated by the well- publicized archaeological excavations of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Like Nuit de Chine, many were presented in flacons fashioned after Chinese snuff bottles, including Jean Patou’s Joy, Roger & Gallet’s Le Jade, and Henriette Gabilla’s Pa-Ri-Ki-Ri, named after a musical revue starring Mistinguett and Maurice Chevalier.

One of the more unusual flacons was created by the Callot Soeurs for the perfume La Fille du Roi de Chine. Shaped after a ”lotus shoe” for a bound foot, it explicitly associated perfume, in Western eyes, with the exotic practice of foot-binding.

(ALCOVE)

Gallery – Saint Laurent & Opium

To this day, fashion’s most flamboyant expression of chinoiserie is Yves Saint Laurent’s extravagant fall/winter 1977 haute-couture collection. In a dazzling mélange of Chinese decorative elements, Saint Laurent reimagined Western ideas of Genghis Khan and his Mongol warriors and the imperial splendor of the Qing court under Dowager Empress Cixi (1835–1908). Of the collection, Saint Laurent commented, “I returned to an age of elegance and wealth. In many ways I returned to my own past.”

His designs merge authentic and imaginary elements of Chinese costume into a polyglot bazaar of postmodern amalgamation. Scallop patterns, pagoda shoulders, and frog and tassel closures are combined with conical hats and jade and cinnabar jewelry to convey a sumptuous, seductive impression of Chinese style as luxurious and glamorous as Paul Poiret’s fantasies five decades earlier.

The collection coincided with the launch of Saint Laurent’s fragrance Opium, a name controversial even in the hedonistic 1970s because of its perceived endorsement of drug use; trivialization of the mid-nineteenth-century Opium Wars between China and Britain; and objectification of women through its highly sexualized advertisement photographed by Helmut Newton and featuring Jerry Hall. Setting the tone for the so-called power scents of the 1980s, the perfume is composed of myrrh, amber, jasmine, mandarin, and bergamot notes.

Film Clips Edited by Wong Kar-Wai: Broken Blossoms, 1919, Directed by D. W. Griffith, (D.W. Griffith Productions, Courtesy of Kino Lorber); Flowers of Shanghai, 1998 Directed by Hou Hsiao-Hsien (3H Productions and Shochiku Company, Courtesy of Shochiku Company) © 1998 Shochiku Co., Ltd.; Once Upon a Time in America, 1984 Directed by Sergio Leone (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment); The Grandmaster, 2013 Directed by Wong Kar Wai (Block 2 Pictures, Courtesy of Block 2 Pictures Inc.) © 2013 Block 2 Pictures Inc. All rights reserved.

Chinoiserie

The idea of China reflected in the haute couture and avant-garde ready-to-wear fashions in this gallery is a fictional, fabulous invention, offering an alternate reality with a dreamlike, almost hallucinatory, illogic. This fanciful imagery, which combines Eastern and Western stylistic elements into an incredible pastiche, belongs to the tradition of chinoiserie (from the French chinois, meaning Chinese), a style that emerged in the late seventeenth century and reached its pinnacle in the mid-eighteenth century. China was a land outside the reach of most travelers in the latter century (and, for many others, still an imaginary land called “Cathay”), and chinoiserie presented a vision of the East as a place of mystery and romance.

Stylistically, its main characteristics include Chinese figures, pagodas with sweeping roofs, and picturesque landscapes with elaborate pavilions, exotic birds, and flowering plants. Sometimes these motifs were copied directly from objects, especially lacquerware, but more often they originated in the designer’s imagination. Chinoiserie’s prescribed and restricted vocabulary directly produces its aesthetic power.

Gallery- Ancient China

China’s varied and vibrant artistic traditions have served as sources of continuous invention and reinvention for Western fashion. Works of art from the seventeenth century onward resonate most strongly with designers. As this gallery and the adjacent gallery reveal, however, designers have also found inspiration in earlier forms, including Neolithic pottery, Shang-dynasty bronzes, Tang-dynasty mirrors, Han-dynasty tomb figurines and architectural models, early Buddhist sculpture and iconography, and ancient Chinese literature, including wuxfa.

These cross-cultural comparisons, as with others in the show, have an appeal that rests on their clarity and legibility that is, on one’s ability to decode the motifs and stylistic references. The comparisons demonstrate how the creative process is inherently transformative, a phenomenon seen here in works of art that boldly reduce a complex matrix of meanings into graphic signs that say ‘China’ not as literal copies but as explicit allusions to a prototype.

The Small Buddha Gallery – Guo Pei

Like their Western counterparts, Chinese designers frequently find inspiration in the aesthetic and cultural traditions of the East. Paradoxically, they often gravitate toward the same motifs and imagery. While it is important to distinguish between internal and external views of the East, such affinities support, at least in fashion, a unified language of shared signs. The small Buddha gallery is devoted to this single gown by the Chinese designer Guo Pei, in which Buddhist iconography provides the primary source of inspiration.

The bodice is shaped like a lotus flower, which is one of the eight Buddhist symbols and represents spiritual purity and enlightenment. The motif is also embroidered onto the skirt. In an act of Occidentalism, the shape of the skirt, which has no archetypes in Eastern dress traditions, is based on the inflated crinoline silhouette that emerged as modish apparel in the West in the 1850s. As with the Western designers in this exhibition, Guo Pei does not practice an exoticism of replication but rather one of assimilation, combining Eastern and Western elements into a common cultural language.

Gallery – Wuxia

For many Western designers, some of the most compelling fantasies of China are in wuxia, a literary genre that is more than 2000 years old and scenes from Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers (2004) and A Touch of Zen (1971) play in this final gallery.

Wuxia, which roughly translates as “martial hero,” relates the adventures of wandering swordsmen whose martial- arts skills are so highly developed that they can internalize their qi (life force) and unleash such superhuman powers as “thunder palms,” “shout weapons,” and “weightless leaps.” The stories often take place in an underworld calledjiang hu (rivers and lakes), in which martial artists cohabit with monks, bandits, and burglars. The heroes are governed by xia, a strict code of chivalry, whose common attributes include justice, honesty, benevolence, and a disregard for wealth and desire. Such traits have led many wuxia novels to be read as expositions on Buddhism, an association played out in this gallery, which displays some of the museum’s earliest examples of Chinese Buddhist art.

Related Content and Programs

A publication by Andrew Bolton accompanies the exhibition, produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, and is on sale. The exhibition are featured on the Museum’s website, www.metmuseum.org/ChinaLookingGlass, as well as on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter using #ChinaLookingGlass, #MetGala, and #AsianArt100.

The exhibition is featured on the Museum’s website, www.metmuseum.org/ChinaLookingGlass, as well as on Facebook,Instagram, and Twitter using #ChinaLookingGlass and #AsianArt100. It is also on Weibo using @大都会博物馆MET_中国艺术

VISITOR INFORMATION

The Main Building and The Cloisters are open 7 days a week.

Main Building

Friday-Saturday

10:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m.

Sunday-Thursday

10:00 a.m.-5:30 p.m.

The Cloisters museum and gardens

March-October

10:00 a.m.-5:15 p.m.

November-February

10:00 a.m.-4:45 p.m.

Both locations will be closed January 1, Thanksgiving Day, and December 25, and the main building will also be closed the first Monday in May.

Follow The Met:

Recommended Admission

(Admission at the main building includes same-week admission to The Cloisters)

Adults $25.00, seniors (65 and over) $17.00, students $12.00

Members and children under 12 accompanied by adult free

Express admission may be purchased in advance at www.metmuseum.org/visit

For More Information (212) 535-7710; www.metmuseum.org

Lia Chang is an award-winning filmmaker, a Best Actress nominee, a photographer, and an award-winning multi-platform journalist. Lia has appeared in the films Wolf, New Jack City, A Kiss Before Dying, King of New York, Big Trouble in Little China, The Last Dragon, Taxman and Hide and Seek. She is profiled in Jade Magazine.