By Lia Chang

AsAmNews Arts & Entertainment Reporter

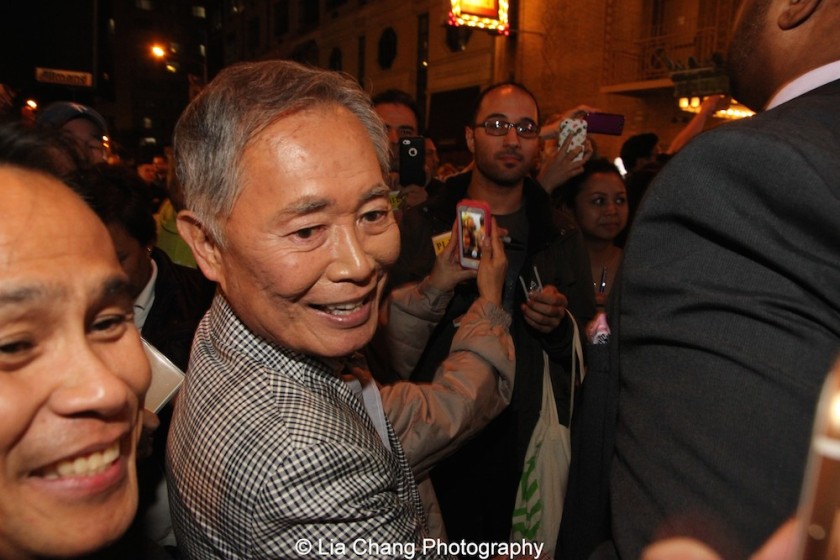

The Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race at Columbia University presented The Politics of Memory, a conversation between Asian American pioneers, Tony Award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang and Star Trek‘s George Takei, on Pearl Harbor Day at Columbia University in New York.

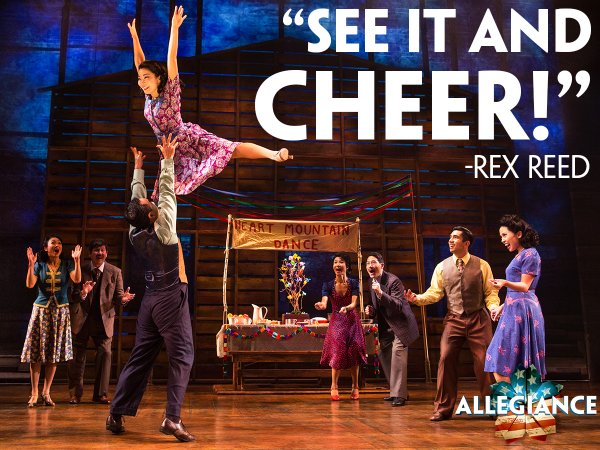

Takei is currently starring in Allegiance, the new Broadway musical, making his Broadway debut opposite Tony Award winner Lea Salonga, Telly Leung and Michael K. Lee at the Longacre Theatre, where Hwang’s Chinglish and Golden Child had runs. Allegiance is a vibrant and unforgettable story of one family’s resilience in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. The play is inspired by Takei’s real-life experience as a Japanese American during World War II.

The talk was preceded by the opening reception of Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Confinement in World War II. The extremely rare collection of color photographs documents the lives of Japanese Americans behind barbed wire between 1943 and 1944. Featuring the photographs of Bill Manbo, a Japanese American inmate, the exhibition is at the Gallery at the Center, Columbia University, Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, Columbia University in New York. The exhibition of photos will be on view through May 12, 2016.

During the illuminating chat, Takei talked about East West Players, his relationship with his father, his memories of being incarcerated as a child, dealing with the aftermath of internment, his passions for social justice, founding the Japanese American National Museum, his views on democracy, being actively engaged, and how the production of his legacy project Allegiance is so incredibly relevant in today’s charged political climate.

Below is a condensed and edited transcript of their conversation, as well as video of Takei’s remarks at the Colors of Confinement Exhibition reception.

Hwang: We have a pretty long history. Can you talk about the founding of East West Players in Los Angeles in 1965? My dad was the bookkeeper for the organization because he was close to Beulah Quo.

Takei: East West Players today is the oldest minority theater in the United States. There was an African American group in Orange, but they went belly up a few years ago.

This Asian American Theater is the oldest continuously operating theater company in the United States. David and I both have an intertwined relationship that includes Beulah Quo, a pillar of the East West Players. She was one of the founders back in 1965. I was there to talk about it, but I was cast in a series called Star Trek. And so I could not be active in the founding of the theater. Almost all Asian American theater artists have some connection with East West Players. It was the organization that did David’s first play, FOB. It’s produced a lot of actors, writers, over the last 51 years.

Beulah and I were active in the performing arena of theater. We were working in a 99 seat theater, first in a church basement, then in a storefront on Santa Monica Blvd. We felt it needed to be a bigger theater. In little Tokyo, we had an historic church that was empty. The congregation had moved on. It was a classic neoclassic piece of architecture, the very first Japanese American Christian Church in Los Angeles. We thought it would be a wonderful reuse project as a theater. To do that we needed money, and we knew someone whose father was a banker, David’s father, who shares the same name, Henry Hwang. He was a very distinguished banker in the Asian American community and the larger financial community. Beulah knew him well, and the two of us went to speak to Henry.

Hwang: He’s really hard to speak to. How did you convince him?

Takei: He’s a very proud man and a very proud father. And that was his vulnerable area.

Hwang: Because at a certain point, my dad said, “We’re going to make this donation to East West and they’re going to name the theater after you.” It’s a little over the top. My first association with East West was in the late 60’s when my mom was the rehearsal pianist for an operetta called The Medium, by Menotti, that was reset in post war Japan. I was about 10 years old and I would hang out at rehearsals. It is not surprising in retrospect that I ended up thinking it was not so strange for Asian Americans to be actors, directors, leaders in artistic organizations when I grew up.

I want to go forward a little to 1975, because other than being really thrilled to see you on Star Trek, in 1965, I turned on my TV and on PBS there was a television adaptation of Frank Chin’s play Year of the Dragon. You played the lead in that. That was hugely influential for me. I was so proud and moved by it. Frank has hated me ever since my own plays got produced, I don’t take it personally. Do you have any Frank stories? What was it like to work with him?

Takei: He is a passionate man. He’s a very intense man, and he is a man who has an agenda. He feels that the whole White world is against him and that’s his big ax to grind. His earlier plays, the ax wasn’t that sharply honed. It was much more accessible, Year of the Dragon. It is essentially a father/son story. The relationship also is with his sister who is married now to a White guy. It takes place in Chinatown San Francisco, his younger brother is now mixing with young Asian gangs and he sees the community and his family changing. He blames it all on his authoritarian father, a self-important father, that conflict there. Father/son stories are always good drama and wonderful roles to play, whether you are the father or the son. I had my fun playing the son, and now I am not only playing the father, but I’m playing grandfather.

Hwang: What was your relationship like with your own father?

Takei: I recognize my father as a very unusual Japanese American. Japanese American fathers are single minded in wanting something from their first son. I was the oldest in the family and a son. He was in real estate. He envisioned me as an architect. I think he fancied the idea of putting out a sign eventually – Takei and Son Real Estate Development. I would design the buildings and he would develop them. On Sundays, my father would take me to construction sites all over Los Angeles. He took me to this great big excavation on Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles. He said, “Here on this end, this big hole, will be an opera house, in the middle will be a mid-sized theater, and the far side would be a larger theater. It’s going to be called The Music Center.” Now it is as my father predicted. He guided me to express an interest in architecture.

As a good son, I began my college career as an architecture student. After two years, I had to be true to myself. My burning passion was acting. I came back down to Los Angeles and I said to him, “I’d like to go to New York and study at The Actors Studio, where all the great actors come from, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Clift.” I began selling The Actors Studio to my father. Apparently, he had done his research.

“Yes, I know about The Actors Studio, it’s a fine, distinguished and respected acting school, but after you finish there, they won’t give you a diploma that says you are a legitimately educated person. Your mother and I want you to have that at least. So I’ve got a deal to offer you, but you’re a bull headed kid, you’re going to insist on going to New York. Let me start off by saying, if you go to New York, let me remind you, New York is a very crowded place, it’s a very competitive place, and it’s a very expensive place. You have to be prepared to do it all on your own. However, in Los Angeles, we have a distinguished university called UCLA and they have a fine theater arts department. If you study there and finish, they’ll give you a diploma. That’s what we want for you. If you go to UCLA, we’ll subsidize you. So you choose. New York on your own, or UCLA.” He was a good deal maker. So I went to UCLA.

Hwang: In taking you to see these places, it suggests that he was able to have a career after the war. How did he deal with the aftermath of internment?

Takei: That was another part of my father that I saw and experienced and my love for him grew even deeper. Our first home in Los Angeles after internment was Skid Row. Those of you that saw Allegiance you know that all we got was a one-way ticket to anywhere in the United States, plus $25. He had 3 children – me, my younger brother and my baby sister, and my mother – a family of five. We each got $25.

The hostility was still very strong. It was difficult to find a job. It was difficult to find housing. But my father, who was block manager at both camps we were in, Rohwer in the swamps of Arkansas, and then we were transferred to Tule Lake. My parents were both No-Nos on the loyalty questionnaire. When we came home, opportunities were nonexistent. Housing opportunities-Skid Row was the only place. And yet because he was block manager, he was giving advice and giving counsel to people on our block, and also representing that block with the camp administration, they came to him for help, even after camp. He opened an employment office in Little Tokyo to find employment, particularly for the older Japanese speaking people coming back. The kinds of jobs that he could find for them was as dishwashers, janitors, gardeners, which paid a pittance. His fee would be a small percentage of that pittance. I remember my mother taking us after school to my father’s office and they would give us employment forms and a box of crayons and we sprawled on the floor in the back room and drew pictures while my mother did filing and my father talked with the clients.

My mother made him quit that because she said we had to eat too. We did that for about half a year, and then we moved from an all-Japanese American community on Skid Row, to an all Mexican American community in East Los Angeles. We felt very welcomed there. It was a minority community of Mexican Americans, immigrants and native born. My father opened a dry cleaning shop with an apartment behind it. I made a lot Mexican American friends who invited me walking back from school to their mother’s kitchen. They would give me bean burritos, fresh made tortillas. My mother made good friends with our neighbor, Mrs. Gonzalez, and she learned how to cook Mexican. I still to this day believe that the best enchiladas and tacos were made by Mrs. Takei, not Mrs. Gonzalez.

Hwang: Rohwer, Arkansas. You were initially in the camps at Rohwer. Another mutual friend of ours and artistic collaborator, Philip Gotanda, the playwright who is a good friend of mine and whose work you’ve done, Philip’s parents were also at Rohwer. Because your parents were No-No’s, you were transferred to Tule Lake, which was the rebellious camp. Did you notice a difference in how Tule Lake was administered? What sort of privileges or freedoms you had vis-à-vis Rohwer?

Takei: Not so much with the administration. My father was the block manager in Rohwer and in Tule Lake. What I remembered about Rohwer was that it was South Eastern Arkansas, it was lush, we were in the swamps. There were trees and lots of water and muck, with cypress roots that undulated up and down in the muck. I had fun in Rohwer. Tule Lake was something quite different, very dry, a dry lake bed. It was sandy, but it wasn’t soft sand of the beach. It was hard sharp gritty sand. When the wind blew, it really cut into your face. Tumbleweeds were always rolling around and it was cold. It was a much more highly secured camp. There were three layers of barbed wire fences. We saw tanks patrolling the perimeter. It was a cold place. Bitterly cold in the wintertime, and in the summer time, it was nice, but still not a pleasant place.

It was also an intensely politicized camp. This was a camp of people that had answered No-No to the loyalty questionnaire. A year after imprisonment, this loyalty questionnaire came down, very sloppily put together. The two most controversial questions were outright offensive and insulting. Everyone over the age of 17 had to respond to it, male or female, 17 or 87, immigrant or American born. Question 27 asked, “Will you bear arms to defend the United States of America?” a year after they took everything from us and imprisoned us. This being asked of a 17-year-old young man, but also being asked and an answer required of an 87-year-old immigrant lady. How is she supposed to say yes to that? It was outrageous. But even more insidious was question 28; it was one sentence with two conflicting ideas. Essentially it asked, “Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America and forswear your loyalty to the Emperor of Japan?”

The word forswear assumes we have an existing loyalty to the Emperor. We’re Americans, born here, raised here. It was insulting for the government to say I have a loyalty; well I was a child and didn’t have to answer that. For my parents to have to say, “ I have an existing loyalty that I will now forswear. So if you answered no, meaning I don’t have a loyalty to the emperor, you were also saying no to the first part of the very same sentence. If you answered yes, I do swear my loyalty to the United States, then you were confessing that you had been loyal to the Emperor and now you were willing to set that aside, forswear it and repledge your loyalty to the United States. My father said, and this line is in the musical, “They took my business, they took our home, they took our freedom, the one thing that I am not going to give them is my dignity. I will not grovel before this government.”

For what I consider to be a very principled, gutsy position, an allegiance to not only your own principle, but principle to what America really stands for, a very American position, they were labeled disloyal and sent to Tule Lake.

Because you have a camp filled with these people, a good number of young men became radicalized. Their attitude was “Alright, you’re going to treat me like the enemy, I’ll show you what you’ll have to contend with. I remember waking up in the morning to those young men jogging around the block, they had headbands that they had painted on the Japanese military flag, the rising sun, and they jogged around with the Japanese cadence Wasshoi, Wasshoi. I remembered hearing that sound as they jogged around the block. And when they finished their jog, they would go, “Bansai.” These were radicalized young men and they were goaded into that position by the outrage committed by this government, the United States government.

Hwang: I finally got to see Allegiance this weekend. It’s really extraordinary. You guys have done a fantastic job. One of the things that I think is amazing from a dramaturgical standpoint is just a series of impossible choices that these people are faced with. They try to navigate through one impossible choice, then that causes another impossible choice, so that there is constantly this vice that’s closing in. It rips apart families and it’s very moving. Congratulations. I think it’s fantastic.

Takei: The credit goes to three very gifted writers Marc Acito, Lorenzo Thione, who is also the lead producer, and Jay Kuo, who is also the composer/lyricist. I have great admiration for them.

Hwang: This project came about happenstancedly.

Takei: I don’t call it happenstance. I call it the theater gods. Brad and I go to the theater regularly, every night sometimes for a whole week. One night we went to see Forbidden Broadway, we’re musical theater fans and a satirical treatment of Broadway musicals is something we find to be a lot of fun too. We were there, it was early, not too many people were seated and we were chit chatting and two guys came in, sat right in front of us and they heard us talking. They heard my voice and one of them turned around and said, “You’re George Takei,” and so we chitchatted. That young man was Jay, the composer/lyricist, who also is a practicing attorney, a brilliant attorney who has argued before the Supreme Court. He’s a man of many talents. The guy with him was Lorenzo. We chatted with them during the intermission. We went back to our apartment thinking, “Oh those guys are really passionate theater lovers.”

The next night we went to see the Tony Award winning musical In the Heights written by another very gifted theater person, Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote Hamilton. We found our seats and we were about to sit down when we noticed two arms waving at us in the same row. We looked over and it was the same two guys waving at me. This time in the very same row. I said to Brad, isn’t that a coincidence, it’s those two same guys. Brad whispered to me, “I think they’re stalking us.”

Then the musical started. It’s a Puerto Rican story which takes place in the Washington Heights area. Near the end of the first act, there’s a bright, very talented daughter who wants to go to college and the father wants to help her get to college, but he can’t. He sings a song Inutil, which means useless. It was a powerful, moving song. Somehow, that song made my mind click to a conversation I’d had with my father as a teenager asking him about our incarceration, and he was telling me about being confronted with the loyalty questionnaire and how difficult, how painful it was for him to respond to that questionnaire. Hearing this song, I’m a weeper to begin with, I started cascading tears. And then of course intermission comes and the lights go on, and the two guys come clamoring over to chitchat again and they see me wiping my tears off my face. They asked me what triggered that and I told them. We started talking about internment. And then we had to quit because the next act was going to begin. We went out for drinks after that to talk some more. And then we decided to have dinner the following night and that eventually resulted in our deciding to work on a musical on the internment of Japanese Americans. That was about 8 years ago.

Hwang: It’s certainly not unusual for musicals to take that long to make it Broadway. The vast majority don’t make it. As the show was going through it’s writing and rewriting process, what did you feel were some of the major things that changed? You originally did a production at The Old Globe in San Diego, and then a few years went by and now you are on Broadway.

Takei: When we opened in San Diego in the world premiere, incidentally the New Yorkers kept referring to our world premiere as the out of town tryout. When we opened there, it was a very enlightening experience. We wanted to make the drama as truthful as possible, but we learned that sometimes you can be too truthful to your disadvantage.

We have one character who is a real character, the others are all fictional. But the events are all true events. The character is Mike Masaoka, the National Secretary of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). He’s a very complex person to begin with. He played a critical role in the internment of Japanese Americans. He cooperated and was complicit in the internment of Japanese Americans, but also the creation of the 442nd. Many of the events that happened, Mike Masaoka was party to. He was also a divisive character. Those that resisted the internment and challenged it all the way to the Supreme Court, were vilified by Masaoka. Those that answered No-No to the loyalty questionnaire, he saw as cowards and traitors because they did not agree with his stance, which was to comply with the government. My parents were No-No’s and obviously I don’t quite agree with that. We tried to depict that truthfully.

We also wanted to tell the epic story of Japanese Americans, the complete story of the resisters, because they get very little spotlight in the telling of the Japanese American interment experience. The 442nd are true heroes. They fought heroically. The 442nd is still the most decorated and the most honored unit of the entire military history of the United States. We wanted to tell the complete story, both sides. We characterized both sides as heroes and used the words that they used.

That fracturing of the community still exists. The other side protested vehemently about the characterizing of Masaoka. We wanted to tell the story. We didn’t want that to become a hindrance to getting the show on Broadway. We took some of the words that Mike used, like calling the resisters, traitors and cowards, and we put that into the fictional character, Sammy and made him a bit less harsh.

We had Masaoka’s nephew see the play in previews and he told us it is a balanced portrayal. Japanese American Citizens League, which he represented, is also active in contributing to that kind of fracture, vilifying one group. The head of the Japanese American Citizens League now, Priscilla Ouchida, saw it and she said it is a balanced portrayal. The former national president of the JACL and the executive director of the JACL wrote a review of Allegiance and said it is a balanced portrayal. He urged members of the JACL to see Allegiance. The characterization of Masaoka was a big change. There were production numbers that we dropped and new ones created. The major one was the portrayal of Masaoka.

Hwang: I also found it incredibly fair and balanced. Even with the JACL complaining about the show before they had seen it, they never actually said it was wrong.

Takei: Well it is their heritage that was portrayed and they were concerned about their legacy.

Hwang: As you are doing this show eight times a week, what are your favorite moments every night? Is there anything that still makes you a little nervous every night?

Takei: Yes. A favorite moment is Ishi Kara Ishi which means stone by stone, it’s a song I sing with my granddaughter.

The theme of Allegiance is transformation. Here this ugly thing happened to us but it made me who I am. I was transformed by that experience. I was defined and shaped by that experience and whatever we do, every little bit contributes to that.

The logo of the show is an origami flower. That origami flower is made out of that ugly hateful loyalty questionnaire. Something hateful treated with art can become something beautiful.

Heart Mountain, that big mountain, can be moved stone by stone. We have this number, the grandfather singing with his granddaughter, a song that he sang from the time when she was a little girl. That philosophy of working diligently to face a big challenge, and that you can overcome it by moving one little bit. That’s a moment that I like.

Hwang: So East Coast vs. West Coast? I am originally from the West Coast as you are. A lot of my shows, we’ve done them on the West Coast first, and then brought them to the East Coast. I always find it harder here as an environment for shows about Asia and Asian Americans. The critical community on the West Coast, it doesn’t mean they like an Asian show more or less, but they understand the context more easily. They live in those waters as it were. I don’t know if you guys have found that with Allegiance, in terms of audiences also, what is your experience having played West Coast vs. East Coast?

Takei: One of things that always concerns me when an Asian American play is done, whether it is on the East Coast or West Coast, we have trouble getting Asian American audiences. Here in New York, I see Asian faces, but it is dominantly White. When I go see an August Wilson play, an African American playwright, there is a dominant presence of African Americans in the audience. That makes a big difference. Then it becomes more viable to get Asian American plays produced when the base audience supports it.

I remember when I was involved in the Civil Rights movement, we went into African American communities, ghetto communities, and every community had a record store. They supported their singers. That’s why we had singers like Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, and Billie Holiday. This is the reason why we have so many great African American stars. Because there is an ethnic base, these talented people became major performers. Same thing with the movies, we have bankable stars like Denzel Washington. We don’t have that base community that supports us in economically significant numbers. Yes, it is theater art, but it is show business.

Hwang: At what point in your life did you ever imagine that you would do a Broadway musical about your experience in the camps?

Takei: To be able to imagine that came much later in life. It’s been my mission in life always to raise the awareness of the internment here in this country, so I’ve gone on speaking tours. We don’t want the story to die off after those of us who experienced it die. We want the story to continue. It is very important to have it institutionalized and so we founded the Japanese American National Museum to do that.

I’ve always thought of it as a potential drama. I wrote an autobiography and I had it in the back of mind dramatizing the first third of my childhood in the internment camps. It was when I met Jay Kuo, he said, “It’s got to be a musical.” He’s a musician. He said, “Dramas are fine, but if you really want to reach people in their heart, and you get them to connect with the characters, a fellow human being, music has the power to do that.”

Particularly with Japanese Americans who are culturally rather contained. We’re not overt in our emotional expression. With a musical, like with Shakespeare soliloquies, you can express your heart, your inner emotions much more effectively.

I didn’t know Jay as a musician when I first met. I didn’t know how good he was. They lived in San Francisco, we live in LA. I maintained an email contact. I invited them to come down to Los Angeles to experience the Japanese American National Museum. I shared with them the word Gaman, which has become a core song through the musical. He went back and two weeks later he sent a song and it was titled Allegiance. It was about the father confronted with the loyalty questionnaire. And there I was at my computer sobbing away again. That song is out, the title remained.

Hwang: Allegiance is so incredibly relevant to the times that this country happens to be in, to the targeting of Muslim Americans, to Donald Trump statements every day. How do you feel about that?

Takei: We live in an intensely politicized society now. For me, every headline has a chilling echo of what happened to Japanese Americans 75 years ago. That’s why Allegiance is so timely, so relevant, when the politicians with a broad brush are characterizing whole groups of people, that’s what happened to us.

Let me tell you a story. The Attorney General of California in the early 40’s was a brilliant man. He was an attorney, knew the constitution, and knew the law. My father used to talk about the fallibility of Democracy. This great man was politically ambitious. He wanted to run for Governor of California. He saw that the singular most popular issue in California was the “Get Rid of the Japs” Movement. So this Attorney General became an outspoken leader of the “Get Rid the Japs” Movement. He made an amazing statement. He said, “There’s been no report of sabotage, spying or fifth column activity by Japanese Americans, and that is ominous because the Japanese are inscrutable. You don’t know what they are thinking. That blank face. So we better lock them up before they do anything.” For this attorney general, the absence of evidence was the evidence.

That fed into the whole national hysteria of the time and we got incarcerated. This man was re-elected twice in California as Gov. of California. And then he went on to be appointed the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. His name is Earl Warren, the liberal Supreme Court Chief Justice. He’s a great man but he had that fallibility. Our democracy is dependent on people who cherish the ideals of our democracy.

Mae Ngai: Please comment on the racial dynamics involved whereas on the one hand we protested Miss Saigon when they hire whites to play Asians. It’s important that Asians play Asians, that African Americans play African Americans. On the other hand, it’s a great achievement that Hamilton has a founding father played by a person of color. I consider it a great achievement when an Asian actor plays Othello. I think it is not inconsistent because it is about struggling for equality and that takes different forms. Can you comment?

Hwang: I think it is a false equivalency to say that people of color play white roles, that it creates some sort of license for white people to play roles of color. The reason is that I would like to look it as an employment issue. 80% of roles that are cast in Broadway and the ten major not-for-profits in New York are cast with Caucasian actors. That would be a bad diversity figure in most industries. That’s why it leads to a certain amount of aesthetic inconsistency, which is – I like it when an actor of color plays a white role because that decreases the 80%. I don’t like it when the reverse happens because that increases the 80%. That’s how we end up trying to create equal opportunity is creating more opportunities for people of color to appear on our major stages and decrease that 80% figure.

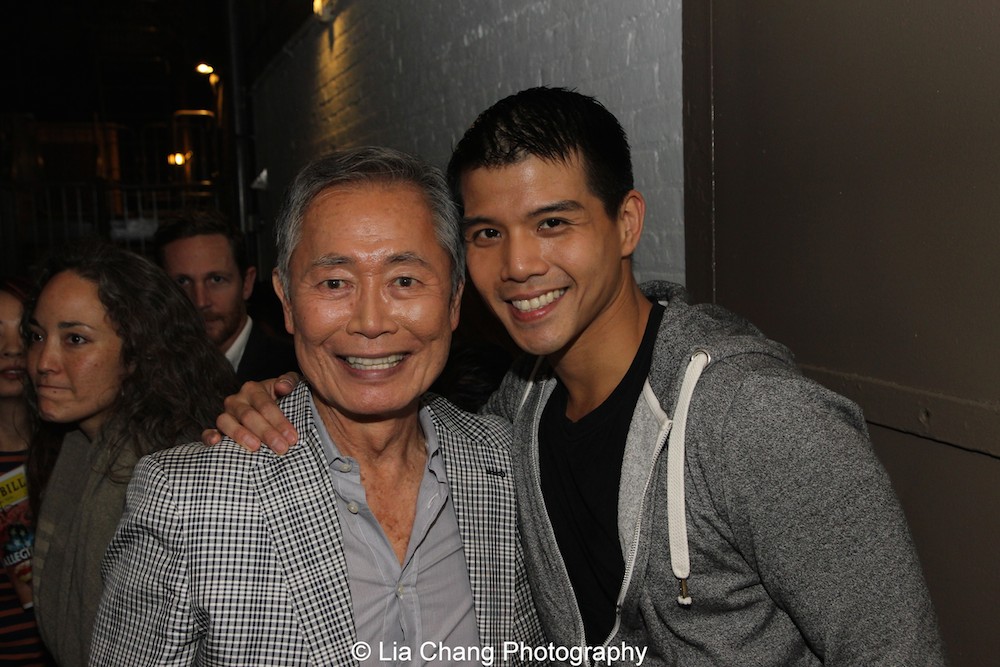

Takei: With Allegiance, we have an Asian American cast for a Japanese American story. We’re actors. I’ve played Korean, I’ve played Chinese, and we all share the same ethnic background. And that’s what counts. Italians can play Spaniards or Polish or Puerto Rican. We are all actors. We create the illusion of truth. Telly as me, Telly Leung playing the young me is very credible. He’s amazing. He’s a wonderfully talented guy. He’s Chinese American, I’m Japanese American, and we are actors. We can play each other. I’m playing the older version of the young Telly and I think Telly is brilliant as me.

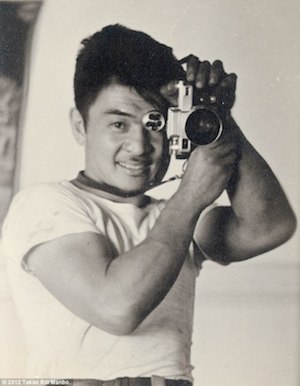

Colors of Confinement, Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II

The photographs on view at the Gallery at the Center, Columbia University, Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, Columbia University, 420 Hamilton Hall in New York, through May 12, 2016, are curated from among the sixty-five images featured in the book, Colors of Confinement, Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II, edited by Eric L. Muller and featuring photographs by Bill Manbo. The book is $35 and can be purchased here.

In 1942, Bill Manbo (1908-1992) and his family were forced from their Hollywood home into the Japanese American internment camp at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. While there, Manbo documented both the bleakness and beauty of his surroundings, using Kodachrome film, a technology then just seven years old, to capture community celebrations and to record his family’s struggle to maintain a normal life under the harsh conditions of racial imprisonment.

The subjects of these haunting photos are the routine fare of an amateur photographer: parades, cultural events, people at play, Manbo’s son. But the images are set against the backdrop of the barbed-wire enclosure surrounding the Heart Mountain Relocation Center and the dramatic expanse of Wyoming sky and landscape. The accompanying essays illuminate these scenes as they trace a tumultuous history unfolding just beyond the camera’s lens, giving readers insight into Japanese American cultural life and the stark realities of life in the camps.

Gallery hours of the exhibition are 10:00AM – 4:00PM, Monday through Friday.

Click below to hear Takei talk about Incarceration, Democracy and Allegiance at the opening reception.

Allegiance has implemented a digital lottery for $39 seats available each day via allegiancemusical.com/lottery. Entries can be submitted the day of the preferred performance, either by 11AM for matinees or 3PM for evening performances. Winners will be notified via email or text, depending on what they select during the entry process, and winners may purchase up to 2 tickets which will be held at the box office. Allegiance will also offer a limited number of $39 rush tickets for patrons 35 years old and under for each performance beginning at the opening of the box office each day. There will be a limit of 2 tickets per customer. Cash or credit cards will be accepted for all lottery and rush tickets, and seat locations will vary depending on availability.

Click here to purchase tickets. For more information go to www.AllegianceMusical.com.

Founded in 1999, the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race (CSER) at Columbia University is a vibrant teaching, research, and public engagement space. The Center’s mission is to support and promote the most innovative thinking about race, ethnicity, indigeneity and other categories of difference to better understand their role and impact in modern societies. What makes CSER unique is its attention to the comparative study of racial and ethnic categories in the production of social identities, power relations, and forms of knowledge in a multiplicity of contexts, including the arts, social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities.

To promote its mission, the Center organizes conferences, seminars, exhibits, film screenings, and lectures that bring together faculty, as well as undergraduate and graduate students, with diverse interests and backgrounds. CSER partners with departments, centers, and institutes at Columbia and works with colleagues and organizations on campus and off campus in order to facilitate an exchange of knowledge.

Click here for more information on CSER.

Lia Chang is an award-winning filmmaker, a Best Actress nominee, a photographer, and an award-winning multi-platform journalist. Lia has appeared in the films Wolf, New Jack City, A Kiss Before Dying, King of New York, Big Trouble in Little China, The Last Dragon, Taxman and Hide and Seek. She is profiled in Examiner.com, Broadwayworld.com, Jade Magazine and Playbill.com.