By Ed Diokno

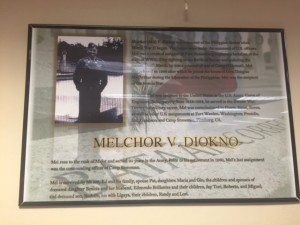

Last week one of my grandnieces lit a candle in memory of my father and about 80 other survivors of the Bataan Death March who had decided to make this California community their piece of the American Dream.

Twenty years ago, there would have been a score of survivors honored. Today, there are none. But their memory lives on in little ceremonies across the United States.

Three generations after the events of World War II, young Filipino Americans are being reminded about their great grandparents. My grandniece never met my father, but she is connected to him as part of the long story of immigration.

The Filipino American soldiers made up what is often called the second wave of Filipino immigration to the United States.

While the First Wave, farmworkers and students of the 1920s are slowly finding their way into the history books especially in ethnic studies in various colleges; and the Third Wave, those who came as a result of the 1965 Immigration Reform Act, are being addressed by contemporary social programs and affirmative action policies; the historic role of the Second Wave is being forgotten as the soldiers grow older and pass away.

Outgunned and without any air support, the U.S. forces fought for months longer than anyone expected. The reinforcements and supplies, including food, that were expected never arrived. They were abandoned by the strategists back in the U.S. The poem below became their rallying cry:

No Mama, no Papa, no Uncle Sam; We’re the Battling Bastards of Bataan.

The battles of Bataan and Corregidor, which fell a month later, resulted in the surrender of 75,000 to 80,000 American and Filipino soldiers on April 9, 1942. It was the largest surrender of U.S. military personnel in history. The U.S. force that surrendered was made up of over 65,000 Filipinos and 12,000 American non-Filipinos.

The prolonged battle delayed the Japanese war machine and forced them to rethink their strategy. It gave the allies time to regroup and reinforce defenses in Malaysia and Australia.

The infamous Bataan Death March that followed the surrender saw thousands of the malnourished, wounded and disease ridden troops perish during the forced march of 40 miles in the tropical heat with little food and water.

the young girls are aware of the debt they owe them

as they take part in Bataan Day ceremonies.

But what is little noted in the history books is the critical role the Filipinos who survived and were part of U.S. units such as the Philippine Scouts when they immigrated to the United States.

Once here, they wanted a piece of the American Dream. Most importantly, they were able to bring their families with them. Their children went to U.S. schools and their wives entered the work force. Despite housing discrimination laws and practices that prevented them from buying in certain neighborhoods or communities, they helped established a stable Filipino American middle-class.

Prior to WWII, the general image of Filipinos in the U.S. was as farmworkers, servants, waiters, domestic help and primarily male. Racist laws limited the immigration of Filipino women, prevented Filipinos and other Asians from buying homes and marrying people of other races in order to start families.

The Filipino image underwent a massive change with the post-WWII immigration of Filipino American soldiers and sailors. The survivors of Bataan and Corregidor were joined by the 1st and 2nd Filipino regiments of the U.S. Army made up of Filipino volunteers who were already in the U.S. Because of the role Filipinos played in the war as U.S. allies, Filipinos became allies, heroes, saviors and comrades-in-arms. In short, it was difficult to not see them as human beings.

Helping change the perception of Filipinos were the thousands of U.S. military personnel who fought along side the Filipinos who proved themselves in battle, whose loyalty was unquestionable and whose belief in America and democracy could not be denied.

It is fitting and important that the accomplishments and sacrifices of the Bataan and Corregidor survivors, most of whom have passed away, are still remembered and honored by their children’s children’s children, their living legacy.

(Ed Diokno writes a blog :Views From The Edge: news and analysis from an Asian American perspective.)

(AsAmNews is an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. You can show your support by liking our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/asamnews, following us on Twitter and sharing our stories.)

RE: Legacy of the Battling Bastards of Bataan: There’s a point of contention between Filipino American activists and the state of California educational system. The state wants to call The Philippines as allies during WWII in the textbooks. And that is wrong because Filipinos were actually American nationals before 1946. Filipinos were part of America and not separate.

I do like the fact that you wrote “non-Filipino American soldiers” describing the other Americans in the article.