By Ed Diokno

By Ed Diokno

SECOND OF A 3-PART SERIES

Western media like to call Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte the “Trump of the Philippines,” but it would be a mistake to oversimplify at first glance a complicated man who through his actions and proclamations, could turn the balance of power in Asia upside down.

Duterte recently announced in front of the Chinese leadership in Beijing, a 180-degree pivot on the long Philippines-U.S. relationship. “In this venue, your honors, in this venue, I announce my separation from the United States.”

What’s troubling is that his pivot towards China and away from America seemed to catch the U.S. intelligence community by surprise. Part of the problem is that the U.S. apparently didn’t take the new Philippine leader seriously, a slight that fed into Duterte’s festering anti-U.S. sentiments.

Like Trump, he has a temper and he tends to speak without thinking. He also takes slights personally and has a long memory on perceived insults. That’s where the comparison ends. Unlike Trump, Duterte is not the poster child of selfish, me-first capitalism. If anything, the Philippine president, a self-proclaimed socialist, is on the opposite end of the political spectrum to the point where his detractors call him a communist.

There has always been a segment of Filipino society that believes the colonial relationship between the U.S. and the Philippines is still in effect; it is so deeply ingrained in every aspect of Filipino life — culturally, economically and politically.

What makes Duterte different from his predecessors is that while he was born into a political dynasty, he is from Mindanao, a part of the Philippines that has been at the center of resistance since Ferdinand Magellan had the gall to claim the occupied islands for Spain. The southern island is the home base of the Muslim separatist movement led by the terrorist group Abu Sayyef.

Duterte doesn’t consider himself part of the Philippine ruling class or the feudal system that keeps the powerful, elite families in power and in influential positions in government and business; all of which is kept in place by corruption, paternalism, private armies and decades of the rich getting richer and the poor masses, getting poorer.

He chose to attend Lyceum of the Philippines University specifically to study under Jose Maria Sison, the long-exiled founder of the country’s communist movement. Sison, living out his exile in the Netherlands, says he nurtured the seed of anti-Americanism within Duterte.

There is a good article in the

Wall Street Journal article that goes deeper into Duterte’s leftist views. Unlike Trump, he is well aware of the rest of the world and how tricky it is to guide the Philippines through this power struggle between the U.S. and China.

What’s not clear is if he knows how dangerous his high-stakes game of roulette is. The long-term danger may be hidden by his short-term successes.

Already, his setting out the welcome mat to China has apparently given Duterte some victories. Filipino fishermen who had been banned by the Chinese military from the Filipinos’ traditional fishing grounds in the disputed Spratly islands are now being allowed to return.

The Philippines and China signed 13 major agreements adding up to a whopping $24 billion in infrastructure, tourism, industry and agriculture. Around 400 of the country’s leading business people, many of them with Chinese lineage, joined Détente in his trade mission.

One of the infrastructure projects the Chinese will take on is the proposed “bullet train” between Subic and Clark, the site of America’s biggest overseas military bases during the Cold War, and a huge train project in Mindanao, Duterte’s home island.

American diplomats’ first reactions did not bode well for repairing the deepening gap between the U.S. and the Philippines.

Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and the Pacific Daniel Russel, who was in Manila when Duterte was in Beijing, met with Philippine Foreign Minister Perfecto Yasay and it did not go well. In short, Russell seemed to lecture Yasay on Duterte’s dangerous language and brought up the killings of thousands of drug dealers that seem to have Duterte’s blessing.

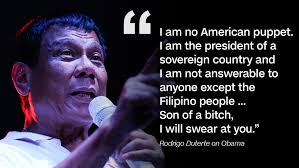

When Yasay relayed the message to Duterte, the president responded in Tagalog: “You tell them, you sons of b——-s, don’t treat us like a dog. Don’t put us on a leash then throw scraps that we can’t reach. Do not … with our dignity.”

What the U.S. fails to realize is how deeply felt is resentment of the America’s cultural and economic imperialism.

Duterte is the manifestation of what many Filipinos feel despite their embrace of American movies, music and fashions; despite being touted as democracy’s showcase; and despite the 20 year wait list for U.S. visas.

Yasay said it more eloquently, “the United States held on to invisible chains that reined us in toward dependence and submission as little brown brothers not capable of true independence and freedom.”

The danger for the U.S. is to simplify and underestimate Duterte, who has the power to overturn the balance of power in Asia and fracture the fragile alliances that took decades to build to counter China’s emergence as a world power.

Related