By Raymond Douglas Chong, AsAmNews Staff Writer

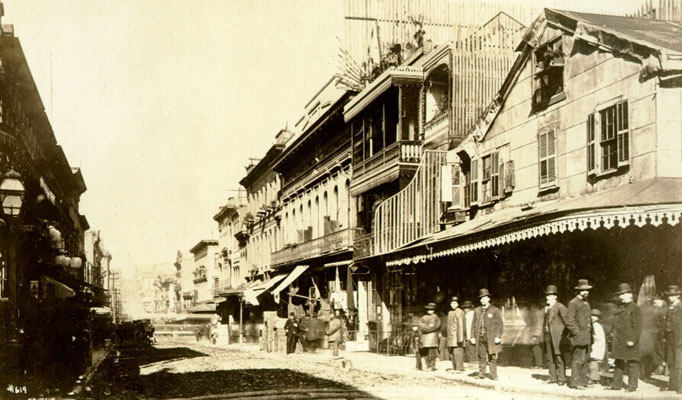

During the California Gold Rush, in 1851, Wah Lee from Sye Yup opened the first Chinese hand laundry in the United States. At the corner of Washington Street and Dupont Street in Chinatown, his small storefront was signed “Washing and Ironing.” It cost $5 to launder a dozen shirts.

A hand laundry was an ideal business for Chinese sojourners. The business required no special skills, no venture capital, and no English language skills. White men considered it undesirable work. Laundry work required long days of exhausting manual labor over wooden kettles of boiling water and hand irons heated on stoves. Chinese men typically worked up to 16 hours per day.

In 1882, Congress approved the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first federal race-based immigration law. It was designed to prohibit Chinese immigration and deny citizenship to Chinese people. Chinese experienced violent crimes and they were segregated in Chinatowns. Rampant racial discrimination prevented Chinese from entering many occupations and businesses. They turned to laundry work because they were prevented to work on other services (mining, fishing, farming, and manufacturing). Working in a laundry posed no threat to White men.

By the early 20th century, Chinese laundries were found in every American city and town. Entire families worked and lived in them. Chinese laundries peaked between the late 19th century and the end of World War II. With technology innovation of washers and dryers and better opportunities for their descendants, Chinese laundries steadily declined.

Dr. John Jung wrote Chinese Laundries: Tickets to Survival on Gold Mountain in 2007. His book was a comprehensive historical, social, and psychological study that included personal stories from “children of the laundries.” Jung grew up and helped with work in his parents’ Sam Lee Laundry in Macon, Georgia. They were the only Chinese in Macon from the late 1920s to early 1950s.

Thirteen years after publication of his seminal book, John shared his thoughts with AsAmNews on one such laundry- the Sun Tong Laundry in Santa Barbara, CA.

The story of the Sun Tong Laundry in Santa Barbara could easily apply to scores of Chinese laundries across all sections of the United States and Canada. Like other Chinese who became laundrymen, Sun Yoke Tong did not do laundry work in China, but opposition from White labor groups and anti-Chinese racism blocked Chinese from work in mining, fishing, farming, and other more profitable areas. They did not “choose” or prefer laundry work but had few other options.

Sun Yoke Tong was among the fortunate few to have a wife and family with him, but the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 and not repealed until 1943, prevented most early Chinese laundrymen from legally bringing family members from Guangdong, forcing them to lonely lives in bachelor societies for decades.

Chinese, like the Tongs, who did have children worked long hours under difficult condition to save enough to provide educational opportunities for them to avoid laundry work and enter white collar and professional careers.

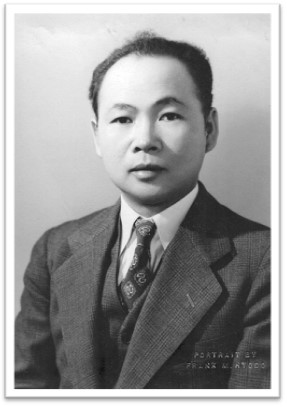

My maternal grandfather, Sun Yoke Tong (Yee) was born on January 11, 1908, during the Qing Dynasty, in Guangdong. He arrived on October 2, 1921 at the Port of Seattle aboard the S.S. Keystone State, a steamer, from Hong Kong. Due the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, he was ineligible to enter the U.S. and had to masquerade as the “paper son” of Woo Ying Tong (Yee) of Los Angeles. As his “paper father,” Woo Ying Tong owned the Cantonese Chinese Noodle Factory in Little Tokyo of Los Angeles.

Sun Yoke Tong eventually arrived in Santa Barbara Chinatown on the Gold Coast to be with Gip Wah Yee, his uncle. During the early years, Sun Yoke Tong lived and worked at the Wah Hing Chung Laundry at 21 West Carillo Street.

Sun Yoke Tong established the Sun Tong Laundry in 1938, with washers, dryers, and steamers, with piles of clothes wrapped in brown paper, at 30 West Cota Street in Downtown. In 1946, he moved Sun Tong Laundry to 26 East Ortega Street across from the Santa Barbara News-Press building.

The Chinese Exclusion Act cruelly separated the men from their wives and children in China, especially during the Civil War in China (1927-1950) and 2nd Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). It was an insular society of bachelors in Chinatown. They faced overt racial discrimination with few opportunities for upward mobility. They were limited to services, laundries, restaurants, grocery stores, and gardens, because of their poor English skills.

The bachelors socialized together and closely bonded during their free times, usually on Sunday afternoons and evenings at Sun Tong Laundry. They ate communal meals, smoked cigarettes, played games, gambled wages, and shared stories. They wrote letters to their loved ones in China. Many eventually left Santa Barbara for better jobs in San Francisco.

Sun Yoke Tong departed on November 21, 1927 from the Port of San Francisco to return to Hoyping, as a Gold Mountain Man. In 1928, Sun Yoke Tong married Tuey Hai Quan in the Ung Yung Village. They followed the traditional Cantonese wedding. She was brought in a bridal carriage from her home village, wearing a red silk gown. After a gift exchange and tea ceremony, they celebrated with a sumptuous feast, highlighted by the roasted pig. They eventually raised six children, Seen Hoy and Donald Chong Yue in China and Rose, Lily, Wallace, and Jeanne in America.

On January 22, 1948, Sun Yoke Tong returned to America from Hong Kong with Tuey Hai Quan on the S.S. General Gordon, steamer. She was pregnant with twins. She arrived at the Port of San Francisco on February 9, 1948. On February 18, she gave birth to twin girls, Rose, and Lily. In Santa Barbara, Wallace and Jeanne were born at the old Cottage Hospital.

The Tong family first lived together in the “warehouse loft” of Sun Tong Laundry. It had kitchen, baths, and bedrooms. In the family compound, they ate communal meals. In the back of the Sun Tong Laundry, Tuey Hai Quan had a chicken coop for eggs. Wallace fed the chickens. Sun Yoke Tong brought their first home on 429 West De La Guerra Street in 1952. They eventually moved to 220 West Cota Street in 1957. It was a Spanish Mission style bungalow with four bedrooms.

Seen Hoy Tong, their daughter, arrived on April 16, 1952 at the Port of San Francisco aboard the S.S. President Wilson, steamer, from Hong Kong. She briefly attended Santa Barbara Junior High School.

Rose, Lily, Wallace, and Jeanne attended Lincoln Elementary School, Santa Barbara Junior High School. and Santa Barbara High School. They were busy growing up with school, sport, and church activities. During school days, after studying, they helped at Sun Tong Laundry. During the summers, they frequently played and swam at the Santa Barbara Beach along Cabrillo Boulevard. Wallace played baseball with Bing, Eddie, and Dorothy Yee in the back lots of Downtown. They went to Sunday School at the Chinese Mission under Miss Graham at the First Presbyterian Church. Rose and Lily attended Santa Barbara City College. Wallace graduated from University of California at Santa Barbara in Goleta.

With their frugal savings, Sun Yoke Tong and Tuey Hai Quan brought several properties in Santa Barbara. They built a small real estate empire with apartments on Castillo Street and another house on Milpas Street. In summer of 1968, they retired. They lived their Golden Years at 4013 Tropico Way, a split-level ranch style villa atop Mount Washington on San Rafael Hills of Los Angeles – The City of Angels.

Sun Yoke Tong died on March 15, 1988. His grave lies buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale with Tuey Hai Quan (died in October 10,1996). They had eight grandchildren.

Into the early 21st century, the Chinese laundries are waning and fading into dim remembrance of an American bygone era.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.