By Ellie Shin

Several years ago, it was a positive occasion when people said they “did not see race.” However, race is essential to both who we are to ourselves and how we appear to others. Usually, one of the first things we notice about other people is their race, and many people may make unintentional biases upon it. In the time of COVID-19, America’s racial awareness is currently on the rise. However, it is not in the usual White/Black view of race that we as Americans are accustomed to; now, people notice the race that has mostly stood in the background—Asians.

THE MODEL MINORITY MYTH

In the past, Asian Americans have been deemed the “model minority.” We were admired for our supposedly superior intelligence, work ethic, and obedience to the law; however, it is critical to note that fulfilling this role of the “model minority” included other stereotypes such as never achieving leadership positions in work, rising to an contentedly upper middle class status, and being generally docile. Asian Americans struggling in poverty or without “innate” mathematical talent were often overlooked or deemed outliers.

In fact, the “model minority” status is a myth, and does nothing but hurt Asian Americans. Like all generalizations, it erases the individuality of each Asian American, and more than that, it erases the differences between Asian ethnicities. Additionally, the myth perpetuates the idea that “if only all minorities worked as hard as Asians do, they too could achieve greatness;” however, this idea only serves to downplay the racism that Asians have been subject to in America, and tacks on that “minorities just need to ‘get over’ any discrimination they have experienced.”

In the end, the “model minority” status is simply a means for America to erase some of its racist history against Asians. By deeming us the “model minority,” America creates the sense that it has always been welcoming to Asians and from that warm reception came the prosperous Asian Americans. Nonetheless, America has never been particularly welcoming to Asians and to this day still struggles with the idea that Asian Americans too are subject to much racism in this country, most recently under COVID-19.

WHEN EVERYONE LOOKS CHINESE

As the death toll rises and more people get sick due to the coronavirus, the general population has searched for someone to blame. Throughout this pandemic, people have verbally and physically attacked Asians and Asian Americans under the guise of protecting themselves from the virus. Many people believe that China is to blame, and therefore Chinese people must have brought the virus to America.

The situation we find ourselves in is reminiscent of both the post-WWII anti-Japanese attitude and the Islamophobia aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. In the face of a crisis, people look for a place to point fingers and are desperate to feel that they are contributing to a cause. Just as South Asians, Arabs, and Sikhs were all discriminated against after 9/11 due to their similar appearances to Muslims, Asians and Asian Americans alike are being targeted in 2020 for our similarities to Chinese people. Asian Americans are attacked regardless of their individual ethnicities.

A Korean man in Indiana was told that “anyone of Chinese descent was not allowed in the store” and chased out of the gas station. A Taiwanese woman accidentally touched a White woman’s bread package in a grocery store; the white woman consequently screamed at her, threw the bread on the floor, and stomped on it. A Japanese-owned restaurant in San Francisco was vandalized, the windows shattered and graffiti painted on the walls. A Korean college student was grabbed by the hair and punched in the face while out walking in New York. A Burmese family, including a two year old and a six year old, were knifed in a Sam’s Club.

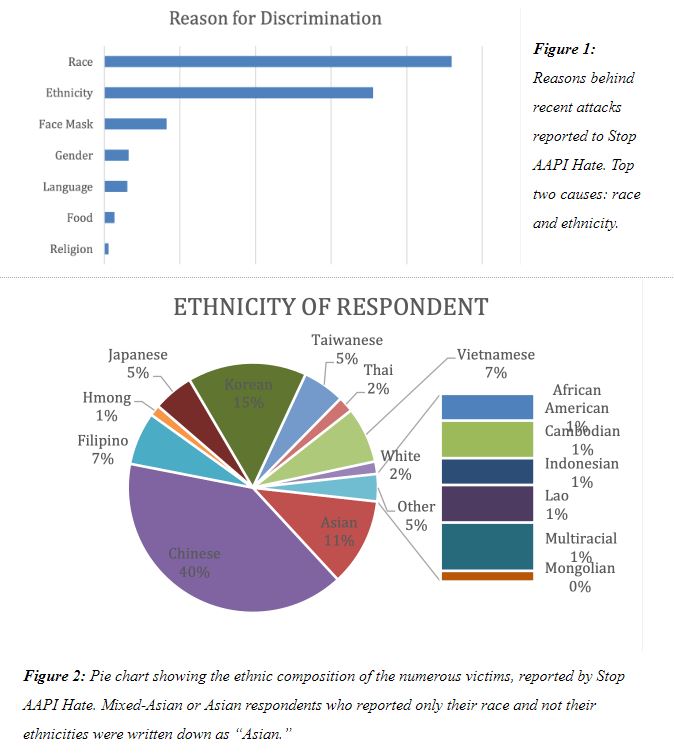

Many of these attacks are recorded by Stop Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Hate, an organization composed of California-based Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council (A3PCON), Chinese Affirmative Action (CAA), and San Francisco State University Asian American Studies Department. Stop AAPI Hate opened a forum for people to report and discuss anti-Asian hate attacks surrounding the coronavirus. In a press release on March 26th, 2020, exactly one week after opening, the organization announced that Asian Americans had reported over 650 incidents of “verbal harassment, shunning, and physical assault.” By the end of the second week, the number had risen to over 1,100 reports.

GUN CONTROL

These attacks have taken a personal toll on my own family as well. My mother is second-generation Chinese American, born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky. My father and his parents immigrated from South Korea when he was less than a year old and have lived in New Jersey for the entirety of their lives. My two little sisters and I are half-Chinese, half-Korean—Asian Americans ourselves. And while we have been fortunate enough not to be victims of any of these attacks, the news has gripped our family with fear.

When we first heard on the news about the Burmese family stabbing, it was a shock that a person could attack someone else just for looking Chinese, let alone take a knife to a two year old’s face. I remember watching my little sisters huddle closer into my dad’s sides. “I’ve been thinking about buying a gun,” he said. I laughed, thinking he must be joking—he had never spoken of buying a gun before and has believed in gun control for a long time. But he continued to explain that “we need a way to protect ourselves, God forbid anyone tries to come into our house.” The news suddenly became real life, no longer just entertainment on the TV. In an effort to lighten the mood, my little sister proposed fighting the attacker with our fireplace poker, which we have always joked would be a good weapon, but I heard only forced laughter.

THE BLAME GAME

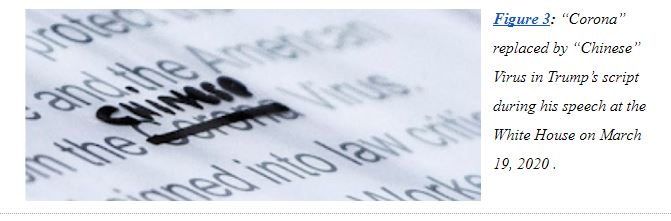

This is not the first time an ethnic or racial group has been blamed for a disease, and it will not be the last. Many countries use the method of scapegoating a minority or political rival to bind the country back together while pushing out the “others.” Often, people in power manipulate situations like a national pandemic to their own advantages: President Trump has been using coronavirus to criminalize China, which he believes will help him win the upcoming election. In the past, his campaigns against trading with China have helped him gain political support, so he looks to do the same with COVID-19. However, by deeming it the “Chinese virus,” he falls into a very recognizable pattern.

When syphilis spread across Europe in the 15th century, Germany and England blamed France, who in turn blamed Italy. The Poles blamed the Russians, the Japanese blamed the Portuguese, the Persians blamed the Turks, and Muslims blamed Hindus. Countries all over the world were locked into one big, toxic round of the “blame game”: in looking for an explanation of a sickness, they turned on one another.

America again deems another virus foreign by calling the coronavirus the “Chinese virus.” It is worth noting that no country has ever named a disease after itself—Americans will never call COVID-19 the “American virus,” despite our current standing as the country with the most confirmed COVID-19 deaths and having contributed to more than 41% of global deaths. Additionally, “racializing” a disease has been in style for a long time. The 2014-2016 outbreak of Ebola in Africa created another opening for just that. People deemed Ebola an “African disease” because it originated in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published research in 2008 indicating that the first case of HIV occurred in Africa—the virus is very closely related to the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) commonly found in African green monkeys. Thus, Americans began speculating as to how a monkey virus had begun spreading among humans. In 2012, Knoxville Senator Stacey Campfield responded to this question in a radio interview, saying that HIV came from “one guy screwing a monkey, if I recall correctly, and then having sex with men.”

Americans terrorized the Black and LGBTQ communities as a result of these theories. When people pushed back, saying the virus spread in Africa because Africans actually hunted the monkeys and that not all homosexual men automatically have HIV, America laughed at African people for eating such a “strange” animal and continued to harass the gay community as they have in the past. The question of morality was brought up repeatedly: African people were asked whether they all ate monkeys and if they were all homosexual; homosexual men were asked if they were all “diseased.” Now, Americans are asking similar questions of Chinese people, such as whether we all eat cave bats and how unsanitary and “dirty” Chinese people are.

This habit of blaming minorities for biological diseases has happened in the past, and it is now happening again. Humanity has always looked to place blame on others; the idea that one could avoid a sickness just by avoiding the people who supposedly “started it” is appealing, and as such, creates deep racial and ethnic divides. However, while humans may discriminate, viruses do not. No matter one’s racial or ethnic background, a virus will invade one’s immune system in the same way it would any other’s. To divide ourselves during times like this is self-destructive behavior.

WITHIN OURSELVES

One day back in February, I read in my weekly New York Times email that anti-Chinese attitudes were breaking out across other Asian countries affected by COVID-19, such as South Korea. At first, I thought of it only as another country, like the U.S., that was attempting to place blame on China as the cause of the virus. However, I soon realized that not only does South Korea think itself significantly different from China, but Korean Americans also think themselves significantly different from Chinese Americans. My grandfather grew up under the shadow of Korea’s Japanese occupation, and he has always viewed the Japanese as cruel because of it. While many may deem such an opinion unacceptable, it makes sense to him after seeing Koreans’ poor quality of life after the occupation.

When I was in fourth grade, each student had to pick one country to research for a large project—I could not decide between China and South Korea, for it felt like choosing between the two sides of my heritage, so I chose another Asian country I had great respect for: Japan. I told my grandpa about the project during dinner, and subsequently was made to sit through an hour-long lecture about the terrors of the Japanese occupation and the brutality of the Japanese military. However, what stands out to me about that memory is how my grandpa, a Korean immigrant, had such strong feelings towards another Asian ethnicity and viewed himself so differently.

In Asia, where Asian people are the majority, it is much easier to create distinctions between ethnicities; however, it is different here in America. In America, Asians are a minority, and we do not have the ease with which to educate other people about each Asian culture or the differences between them, especially now. These days, Asian people are assaulted not just because people blame China for the coronavirus, but also, at a more base level, because of how Asian people look—we all look the same to other people, and thus they will harass us just because we resemble the Chinese people across the world. To the attackers, it does not matter if we were born and raised all our lives here, if we are Vietnamese, Mongolian, Japanese, Hmong, Korean, Indonesian, Chinese, or any other Asian ethnicities.

To many Americans, we are simply dangerous—many of them assume that we carry the virus, that we are more likely to contract the virus. Just this past week, my family and I were out walking in the nearby neighborhood. We carried masks, as we always do, and put them on when people came closer. When we passed a trio of White teenage girls, they promptly crossed to the other side of the street. One of them held her shirt up over her nose and mouth and scowled at us. I’d like to think that my family’s race was not a factor in their decision to cross the street and that they were just keeping themselves safe. However, I cannot help but imagine that they looked at my family, a group of five Asian people wearing masks, thought that we must be Chinese and have the virus, and then crossed the street to avoid us.

Perhaps I suffer from self-inflicted paranoia. I have known many friends of minority ethnicities who suffer from the same. Once we know that some people see us a certain way, we begin thinking that all others see us in that same way; sometimes we even begin seeing ourselves in that way. In knowing that many Americans blame Chinese people for the coronavirus, maybe I have convinced myself that those White girls thought my family was sick. Maybe I even imagined the scowl on one of their faces.

HOPE

In the end, I am sad that these attacks are taking place here in America, where people like my grandparents have come to live a better life. I am sad that many Americans see only our exteriors, still make racial generalizations, and cannot stop the xenophobia that has crept over our country since President Trump’s inauguration.

I have realized that it is difficult for me to understand my grandfather’s sentiments towards Japanese people because, at the root of it, I am not like my grandfather. He was born and raised in South Korea; I was born and raised in America. Additionally, while my grandfather is wholly South Korean, I am two Asian ethnicities: Korean and Chinese. In school, my classmates have always said things like “wait what? You’re half Korean? I always thought you were just Chinese” when I made a passing comment about my Korean heritage. It is almost as if people consider it strange to be half of one type of Asian and half of another. It is almost as if you must be one or the other, and to be in between is to be foreign to both.

For ages, Asian people have been divided—we do not think of ourselves as one, but rather as each individual ethnicity. Euny Hong, a Korean American journalist and author, recently wrote an article titled “Why I’ve Stopped Telling People I’m Not Chinese.” Hong grew up with internalized racism and had a difficult time dealing with it. She admitted to deflecting racist comments away from herself and towards Chinese people instead in an act of self-defense. She wrote:

When I was a kid in late-1970s suburban Chicago, anti-Chinese taunts were a daily occurrence. It was a frequent topic at Korean church — the only place we clapped eyes on other Koreans outside our own homes. Our parents and Sunday school teachers told us that the correct response was, “I’m not Chinese; I’m Korean.”

None of us kids were proud of being Korean American back then. The grown-ups tried to counter this shame by instilling ethnic pride. But despite their good intentions, they invited pride’s ugly sibling: implied permission to step on other people.

Hong reflects on her childhood with a new sense of clarity during the events of COVID-19, realizing that the mentality she had held dear for much of her childhood was wrong, that attacking people based on their ethnicity is not and should not be allowed, regardless of whether people are attacking you for an ethnicity that is not even yours. Hong writes, “If someone says, ‘You Chinese are killing us,’ I am in that moment Chinese.”

However, I keep reading about the attacks and talking to my friends and family about them, and in the midst of all the sour feelings, I have found a silver lining. Despite all the terrible events of the coronavirus-incited racism, I believe that the Asian American community can emerge from this victorious and stronger than ever.

I know my family is not the only one who sits around the dinner table a little quieter these days, who argues about whether it is safe to go visit family in California, who turns on the television to more news of attacks and promptly turns it back off, any excitement for entertainment squashed. In the end, we can learn to accept and self-identify under the Asian American label, because like it or not, we are already perceived in that manner.

Making it through these tough times requires a little bit of compromise in order to achieve the best for all, and by uniting through our shared experiences, I believe that many will find it is not so bad to “generalize yourself.” After all, “Chinese Korean American” is a bit of a mouthful, so I think I am content to be an Asian American.

(About the Author: Ellie Shin is a rising high school senior living in New Jersey. As a third-generation Asian American (half Chinese and half Korean) she believes that racism against Asians is far too normalized in America and that forming a joint Asian American community is the first step toward realizing our strength as a people. Ellie aspires to study biomedical engineering in college and beyond, with special interests in genetics and the visual arts. In her free time, she practices squash, listens to music, plays the piano, and spends time with friends and family.)

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.

Beautifully written. Kudos Ellie Shin!