By Nathan Reddy, Community Works Magazine

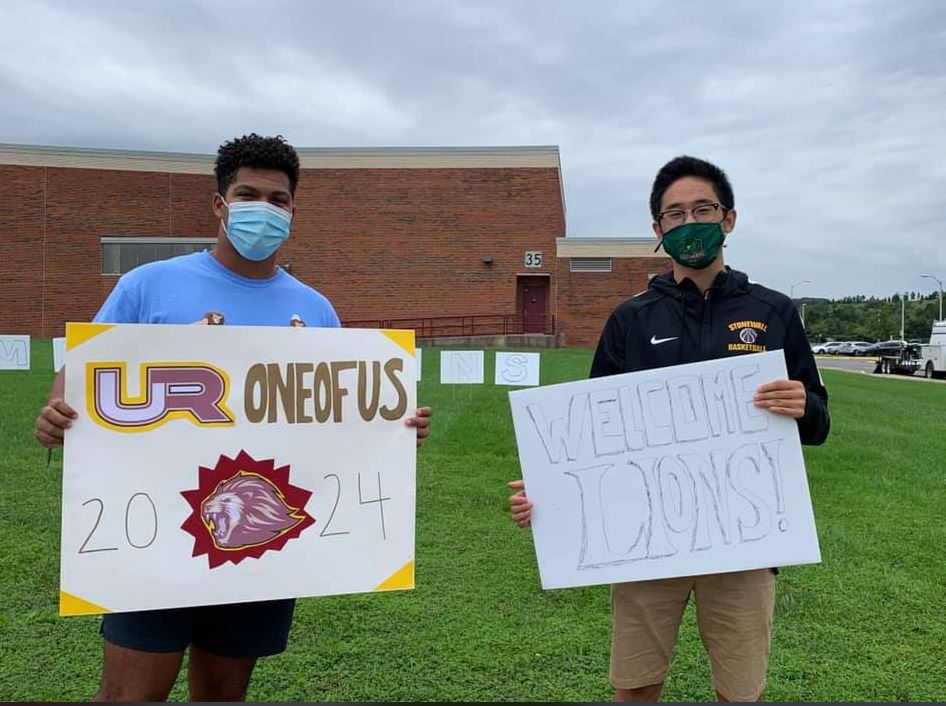

I went to Stonewall Jackson High School in Manassas, VA, the alma mater of Dr. Ibram Kendi, fun fact. But that’s not the only reason it’s notable. “Stonewall Jackson” is no longer its name. It was changed to “Unity Reed” as a result of the recent mobilizations for racial justice (Stonewall Jackson was a notable Confederate general), starting with the murder of George Floyd. “Unity,” representing what we would like to accomplish at the school and ultimately society, and “Reed,” to honor a beloved and late custodian.

I did well at Unity. I graduated as the Class of 2014 Salutatorian. I believed that I had worked hard, and I did. It was a grueling several years of balancing a perfect GPA, attaining a high SAT score, all while engaging with multiple extracurriculars. It was hard. As a child of immigrants, my high school success meant redeeming the sacrifice my parents made in coming to this country from India. The American Dream. I worked hard for their approval. To psychologists, especially those specializing in Asian American psychology (which has its own journal), this dynamic may seem toxic. But it’s more complex than analyzing the immigrant child’s psyche; mine was not created in a vacuum, but like everyone else’s, was formed within a sociopolitical and socioeconomic context. Many reduce that context to “culture” as a way to explain Asian American success, but to do so is a disservice to racial justice, as it advances the model minority myth. This myth that pits minorities against each other and justifies oppression against other people of color, especially Black and Latinx people.

So, to be clear, this analysis of my positionality as a Unity Reed high school student and its local racial politics is yet another effort I make towards freeing myself from the model minority myth. Let’s start with when I was most immersed within it, as a student at Unity Reed.

I did work hard; I won’t deny that. But as I implied, I was working within a privileged context that allowed my hard work to be validated through social structures that paved my way towards material and professional success and mobility. I am a child of immigrants, but my father works as a scientist for the federal government, a stable and high-paying job. As a result, we had the resources to live in a middle-to-upper class neighborhood, which is majority White (like the projects, the suburbs have been diversifying too—which is not ameliorating the severe economic stratification of society, I might add). I was freed to devote all my time to academics and extracurriculars, while most Unity Reed students were low-income and Latinx.

They simply did not have the time to take the work-intensive International Baccalaureate classes and do multiple extracurriculars because they had their hands full helping to support their families. They worked hard, but their hard work was not an investment in their own academic success, it was to help their family get by. In this way, privileged students who attended Unity Reed were able to climb to the top of the ranking ladder, while I almost made it to the apex. To be clear, there were many students from all different socioeconomic backgrounds doing well at Unity Reed, even valedictorians on free or reduced lunch. The school administration also did a great job in furthering access to IB courses with their introduction of the IB Honors program, which had less requirements than the recognized Diploma program. As a result, the IB classes were relatively diverse. Those individual successes, and programmatic policies, however, do not justify the injustices of systemic racism that prevent most Unity Reed students from engaging in academics as much as I did.

Therefore, students who lived in my neighborhood had the upper hand at Unity Reed. However, this wasn’t even enough of an incentive to get them to stay. While I was at school, there was a “social movement” to have my neighborhood zoned to another school. That school is, unsurprisingly, majority White, just like the demographics of my neighborhood. This is an American story. Many of the reasons to move centered around “home values,” their children not being able to stay friends with their middle school buddies, etc. Apparently, academics didn’t matter because the IB Program at Unity Reed is literally world class. It even was TIME Magazine’s School of the Year 2001. The accolade, however, could not diminish the fear White parents had. Apart from the official reasons stated at town halls as to why they believed Unity Reed was not the school for my neighborhood, I knew about their race-based fears.

Since the early 2000’s, the area had experienced a wave of Latinx immigration, primarily as a result of intense development and the working-class people needed to accomplish it. As a result, Unity Reed enrolled an increasing number of minority students each year, and White parents grew increasingly uncomfortable. Parents grew concerned for their children’s safety, as Unity was alleged to count gang members among their ranks. I knew this because at my middle school, children innocently spoke about what their parents said behind closed doors. The particular gang that they were scared of was MS-13, which is now famous because the Trump Administration used it as a political strategy to deter progressive immigration reform. Well, parents in my neighborhood were ahead of him. I heard rumors that students at Unity wore red and black, repping their gangs in full view of their teachers.

I am part of the Indian American community here in my neighborhood, and the parents were open about safety concerns at Unity too. They were also worried that their children would not be able to get into “good” schools if their children attended Unity. For the record, that is a legitimate concern, at least in so far as the reader cares about US News college rankings. The more well-funded a high school is, the more students are admitted to prestigious colleges. Unity is the least funded high school in Prince William County.

I attended this county town hall one of the times I visited home during college. It was about the multimillion-dollar investment in athletic luxuries, and the building of more schools (with swimming pools). The people who spoke talked about how their teams weren’t getting as good equipment as that other school, etc. This was not the place for my comment, but I made it anyway. I said it was great that these schools were getting these amenities (to be polite), but I was an alum of Unity, and that school was frankly falling apart (in terms of infrastructure and maintenance). Because politicians love coded messages, I ended mine with one. The United States, including our area, is getting increasingly diverse whether we like it or not. How about we stop fearing it and seeing it as a negative, and viewing it more as an opportunity to create a more healthy, functioning democracy?

I received a lot of mean stares from others. I made my point.

Let’s call it what it is. They did not want their children interacting with their Latinx counterparts. This is an American story. Why don’t these families want their children to attend Unity for the sake of having them understand how to engage in a globalized society, and gain a deep appreciation of diversity and its interrelation with democracy? If such questions sound ludicrous, then that only highlights the problem. There’s more than one American story, and another one in particular is the one about integration. People in prior generations put their lives on the line, and some died, to realize Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream. Now, however, we completely accept deep racial segregation as a given. It is not.

I wonder if any of these parents read a copy of How to Be Antiracist. If they did, it is ironic that they are receiving instruction from an alum of Unity, a school they are fighting to have their children not attend. They’re not racist! They’re just concerned for their children’s “safety,” and they have a Black friend. This irony points to a profound political truth: that anti-racism is akin to pro-democratic efforts, and the story of America that we all should be living for is the one where people from all different backgrounds and experiences come together, living and working together, the “beloved community.” That is the America that I want to live in, and I regret that it was not the America I grew up in. But that regret has profoundly influenced what I want to do in my life, and that is be an elementary school teacher in the Manassas area. I want to do my part to realize Dr. King’s dream for myself. To immerse myself in the company of children who have different experiences and identities than mine, for the sake of learning from each other. Unity is the story of America, but it will take more than a name change to fight the inherently anti-democratic forces of White supremacy. It will take a change in consciousness, a consciousness which understands that the greatest education is one of immense diversity, because without difference there would be nothing to perceive, and therefore nothing to know.

Even though their efforts to get rezoned multiple times were struck down, I heard that the very latest one was successful. Great. Regardless, for years parents figured out ways to transfer their students to other whiter and more Asian schools anyways. So, I guess the movement “won.” The Civil Rights Movement lost, and Dr. King’s dream is becoming even more of a fantasy day-by-day. At the very least, at least I have a new American Dream.

About the Author

Nathan Reddy recently graduated from Cornell with a BA in American Studies, with minors in Asian American Studies and Public Service Studies. At the same time of graduation, he had also completed the Cornell Public Service Center Scholars Program, the University’s service-learning program which he says, “personally made college worth it, intrinsically and because it inspired me to become an educator myself.” He says that this essay chronicles his experience details as someone with an Asian American identity grounded in service-learning principles, and how that perspective informs the way he operates in the world, now and in the future. Nathan is a regular contributor to Community Works Journal and is currently a Fellow with Community Works Institute (CWI)

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.