Possibly Hoshi Dan group at Tule Lake concentration camp, c. 1943; Photo by Frank Abe via Densho

By Derrick Hills, AsAmNews Intern

December 7, 1941.

Many Americans know the significance of this date: The day the Japanese navy launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The day the U.S. officially joined World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it “a date which will live in infamy.” And for all Americans, it was. But for over 280,000 Japanese American civilians throughout Hawaii and the continental United States, the attack on Pearl Harbor further made them targets for growing anti-Japanese hate and discrimination.

Facing heightened wartime hysteria, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed EO 9066. With this order, the U.S. government forced more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast to leave their homes and livelihoods behind. Pushed onto crowded trains and buses, Japanese Americans were then shipped out to one of ten hastily-built Japanese concentration camps in the country’s interior.

79 years later, many stories of WWII Japanese American incarceration are preserved through the memories of camp survivors and their descendants — as well as several Japanese American cultural institutions, museums, and organizations throughout the nation.

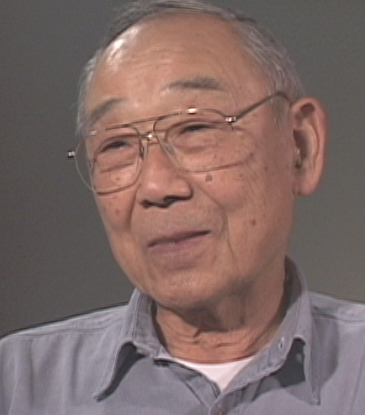

Following the release of Campu in September, AsAmNews interviewed a survivor of one of these concentration camps, Homer Yasui. Reflecting, Yasui shared about his life as a Japanese American during the war years — and now, in 2020. The interview can be read below:

Derrick Hills / AsAmNews: Please introduce yourself. What is your background? Where/when were you born, and which camp(s) did you or your family spend time in? If it’s okay, would you be able to share a little bit about what you or your family did before, during, and/or after camp?

Homer Yasui: My name is Homer Yasui. I was born and reared in the little town of Hood River, Oregon in 1924. I was one of 9 siblings born to Masuo and Shidzuyo Yasui, both of whom were immigrants from Japan. My father came to America in 1903 and my mother in 1912. At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, there were only four of us living at our home in Hood River: my father, my mother, my youngest sister, Yuka (then age 14) and me (then age 16). My father was arrested by the FBI/HR Sheriff on December 12, 1941 and interned at various INS camps until mid-January, 1946.

(Note: INS = Immigration and Naturalization Service)

On May 13, 1942, My mother, Shidzuyo, and Yuka and I were sent by train to the Pinedale “Assembly” Center, which was located about 5 miles north of Fresno, CA, which held the Fresno “Assembly” Center. There were over 500 of us Nikkei on that prison train. Around 490 of us were from the Hood River Valley, but there were other Nikkei from the little town of Mosier, The Dalles and from Wasco County in Oregon, and from White Salmon, Bingen, Mary Hill and Dallesport, Washington.

(Note: Nikkei = a person of Japanese ancestry living outside of Japan)

I worked as an Orderly in the Pinedale Infirmary, and was paid $8 a month, because that was considered to be “unskilled” labor — any fool could do it. The semi-skilled workers, such as typists, clerks, assistant teachers were paid $12 a month: and professionals, such as doctors, pharmacists, teachers, ministers, lawyers, were paid $16 a month.

I also worked as an Orderly at the Tule Lake camp hospital. This was a sort-of, put-together wooden hospital, although I doubt very much that it was accredited by the American Hospital Association. Here I was paid $12 a month for the same job that I had done in Pinedale. The semi-skilled got paid $16 a month, and the professionals were paid $19 a month. $19 was the top pay in the “camps”, because I believe that the WRA didn’t want us camp “colonists” to be paid more than the $21 a month that a Private in the U.S. Army was getting paid… or so I heard.

Temporary hospital barracks at Manzanar concentration camp, c. 1942 by Dorothea Lange via Densho

I was in the Tule Lake WRA (War Relocation Authority) camp until around September 23, when, with 3 other college bound students, we left for the University of Denver aboard a bus.

I attended the University of Denver (also sometimes called Denver University, or “DU”) until around August 1945, when I left for Philadelphia, PA to attend the Hahnemann Medical College and Hospital. During the war years, most colleges had “accelerated” their curricula to carry on even during the summer months, so it was possible to earn a college degree in three years. And on and on and on.

DH: What are you doing or where are you residing now?

HY: I live in a retirement complex for seniors (“elders”, as they call us) at The Lakeshore, which is located in unincorporated South Seattle at the southern tip of Lake Washington. Since the COVID lockdown, I spend maybe 4 – 6 hours a day at my computer, watch a whole lot of CNN, and mess around fixing different Japanese foods that I have a craving for. Also, doing a lot of writing for my descendants about our family history in America.

DH: Why did you decide to share you and/or your family’s stories? Has sharing your story changed or influenced your life at all?

HY: I’m one of the “camp” survivors, and my memory is still pretty good, so I want my family, particularly, to know about our family’s history in general, and our wartime history in particular. However, I want more than just my family to know about our wartime “camp” experiences — I want everybody to know about that.

I’ve been involved with the Japanese American community and its/my/our activities since 1970, when I joined the Japanese American Citizens League in Portland, OR. Over the years, my late wife and I had talked to, and held slide show presentations to, many different groups, mostly students ranging from elementary schools through college.

Sure, getting ready for those presentations required a lot of reading and researching, so today I am quite comfortable talking about the “camps” and my experiences in those “camps”.

DH: What do you hope is gained or learned through projects like Campu which share the Japanese American camp experience?

HY: I’m not great on podcasts, mainly because while I know that the people are saying something, I have a heck of a time [hearing] what he/she/they are saying. As a result, I rarely listen to podcasts…

Still, I approve of projects like Campu, because it passes on information that people should hear and learn about, because it happened in our great land of freedom — and knowledge like that should be the first line of defense to keep it from happening again.

DH: In your opinion, how has the Japanese American community transformed throughout your life — or if not, how has it stayed the same?

HY: It’s changed — just like almost everything else in the United States. I think that the Nikkei communities have gotten much more liberal — more progressive — than the old Issei-led Japanese communities that Nisei like me grew up in.

Much of the Meiji-era Japanese dialects and language, customs and traditions brought over from the old country by our Issei parents are no longer observed or understood — as in any other immigrant communities who come to the new world.

But what has NOT changed, in my opinion, is our attitude towards Japanese food. I think that most American Nikkei like rice far more than they like bread; and I think that we Nikkei are completely satisfied that nobody can fix fish like the Japanese.

DH: If applicable, how did you feel about the Japanese American community throughout your life as compared to now? Have your perceptions of the community or your perceptions of yourself changed?

HY: For me, my perceptions have changed… a lot. In my younger days — up until the time when I got married at age 25 — I thought that the epitome of success was to be a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant male — the classical WASP.

But I haven’t felt that way in years, because I realized that’s a manifest impossibility, and besides that, maybe being a WASP isn’t so grand, after all, judging from the actions of great Americans such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Earl G. Warren — who were responsible for putting the West Coast Nikkei in those abominable “camps” during WWII.

So for years I’ve identified myself as a Japanese American who is very proud of his Japanese heritage.

DH: Is there anything you think is done particularly well about Japanese American Studies and the telling of Japanese American wartime stories today? Is there anything you wish you could add, change, take away, or improve?

HY: The two Nikkei organizations that I think that have done especially well in telling the story of the Japanese American experience in the United States are Densho and the Japanese American National Museum.

Of the “Camp” experience, I think that the Heart Mountain Foundation does it the best.

I think that the Japanese American Veteran’s Association (JAVA) and the Go For Broke Foundation tells the story of the Nisei Soldiers’ stories the best.

I have no opinion as to which of the Asian American Studies programs in academia does it particularly well.

More information about the Pearl Harbor attacks and its effects on people of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii and throughout the United States are available on Densho, including additional interviews with Homer Yasui and other Japanese incarceration camp survivors in the Digital Repository.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.