By Rhiannon Koh, AsAmNews

Despite being part of the United States’ story, the Asian American community and their diverse experiences have been largely ignored and sanitized in educational materials. This limited narrative has had devastating consequences, especially since the highly politicized outbreak of COVID-19.

Paired with the social justice protests that surged after George Floyd’s death, the conversations of race and immigration gained more traction in the United States when it came to whose stories were told—or not. At the heart of this transformation is the Immigrant History Initiative (IHI), a non-profit organization dedicated to creating a curriculum that celebrates and highlights the centrality of immigrant experiences in the American identity.

AsAmNews had the opportunity to speak with co-founders Julia Chang Wang and Kathy Lu.

“We started the organization back in 2017 after seeing what the [2016] election had done to normalize the rhetoric against immigrants and against people of color,” Wang explained. “We felt that learning history was really an important piece to understanding why certain stereotypes and certain kinds of discourses are really problematic.”

“For us, it just seemed like our mission and our work was more relevant than ever,” Wang continued. “We had always emphasized the intersectionality of experiences raised in immigration and gender.”

Both women graduated from Yale Law and their studies in law and history have shaped the organization’s direction. Julia received a Gates Scholarship to study and obtain her Masters in History at the University of Cambridge. She has published several articles on immigration and Asian American identity. At law school, Kathy led the Asian Pacific American Law Student Association and the Immigration Legal Services clinic. She has worked as a nonprofit attorney with Asian survivors of gender violence and vulnerable families of color.

Through the Immigrant History Initiative, they’ve crafted workshops, courses, and resources that work to change how society learns, talks, and thinks about race, migration, and social justice. As the children of immigrants, Wang and Lu also stress the importance of building community through education and preserving such narratives for future generations.”

The IHI offers a wealth of resources from AP United States History lesson plans to anti-Asian racism and COVID-19 resources. The organization works across several states in the Northeast including New Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Developed materials align with the respective states’ curriculum standards. The IHI also has a national reach through its website and social media.

During the uptick in attacks against the AAPI community, Wang and Lu shared that demands for their organization’s services dramatically spiked.

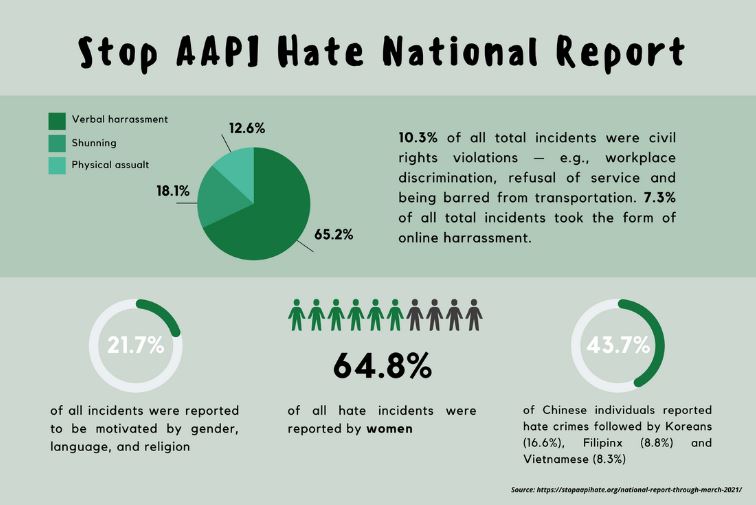

Between March 19, 2020, and June 30, 2021, the Stop AAPI Hate movement recorded a total of 9,801 reports of hate incidents against the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. The FBI also reported a 76% increase in hate crimes against Asians within the last year alone.

“I remember we had dozens of requests from Asian American parents asking us for resources on how to deal with anti-Asian violence, on how to understand it, and how to talk about it with their children because they had never had these conversations before,” Lu said. “Parents would say, ‘I want to know how to talk to my kids if they see me get attacked on the street, if they see me get spat on, or cursed at. I need to know how to talk to my kid about it and help them the process that trauma.’”

Lu said that the IHI put together workshops that specifically focused on the AAPI family space. The discussions facilitated intergenerational conversations that supported children and their parents. She said, “We also gave the parents some of that needed space to reflect on experiences that happened even before the pandemic… it was heartbreaking.”

The IHI also provides parents with a guide on how to talk to their children about Asian American identity and racism. The guide comes in 7 different languages including English, Hindi, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, Nepali, Tagalog, and Vietnamese.

The IHI is currently working on expanding its resources. One such plan is to create materials for K-5 children. Curricula about Asian American & Pacific Islander histories are often taught at high school or university levels. Consequently, the IHI plans to remedy this by introducing age-appropriate stories to early audiences.

Wang also shared that the IHI is working to create a hub of resources not only in Asian American history, but also for African American, Black, Latinx, and Chicanx history. Additionally, the IHI is planning to launch a community pilot program.

“At our core, we really believe that historical knowledge shouldn’t just be in schools. It should be across institutions, and it should be with the communities for whom their daily lives are affected by this history,” Wang said. “We want to launch a program that provides AAPI communities with tools to think about what it means to be leaders and activists, especially for this next generation. AAPI individuals and communities clearly have a stake in racial justice.”

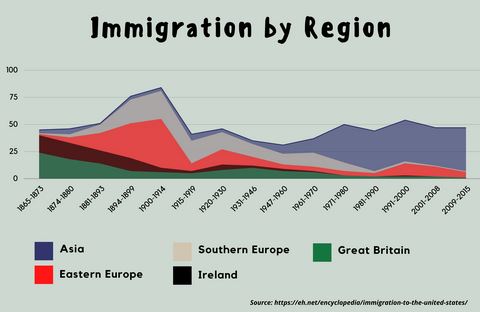

Wang and Lu chronicled the United States’ virulent history towards immigrants, particularly Asians. The Chinese were the first ethnic group to be explicitly banned from immigrating to the U.S., a legal decision known as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. The legislation was continually refined and culminated in the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, an immigration nationality act that banned all immigrants from Asia in addition to setting very strict quotas for Eastern European immigrants.

“When you look at the rhetoric and the depictions of Asians in the speech that John F. Miller made to the Senate in support of the passing the Exclusion Act,” Wang said, “Asians are depicted as vermin. They’re depicted as rats. They’re depicted as machines. You see a lot of this very early on.”

The Exclusion Act was officially repealed in 1943. Both Wang and Lu believe that these six decades were critical in shaping anti-Asian sentiment, which effectively condemned Asians as ‘perpetual foreigners’ in the centuries to come.

“America’s first immigration enforcement team was created specifically to find and expel Chinese immigrants,” Lu elaborated.

“This was in the very early 1900s where they put this team of agents together at the border. They called themselves ‘Chinese catchers’ because that’s what they were doing. These ‘Chinese catchers’ were tasked with finding these Chinese migrants and then deporting them. This is literally America’s first iteration of ICE and CBP. We did not have these government agencies before this time and they were literally put into existence to expel Chinese people and later, other Asian people.”

Wang added that these events were products of nativist movements that stemmed from the early 1860s and 1870s. Along the west coast of the United States and Canada, there were massive riots and mob violence that were specifically targeted to drive Asian communities out of town. Wang cites the 1885 Rock Springs Massacre in Wyoming where over a dozen Chinese men were lynched.

“When people say, ‘Why is there such violence now? Why is there such virulence against Asian Americans?’” Wang said. “It’s because it’s been embedded in this history for hundreds of years. It’s no wonder that it’s so easy for Asian Americans to be vilified today because, in a lot of ways, they’ve always been a target.”

American military intervention in the last half-century has also been equally influential in shaping perceptions of Asians at home and abroad.

Most of the Asian Americans in the United States today did not come until the 1965 Immigration Nationality Act. Furthermore, American military involvement in places like Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Laos sparked a mass exodus of refugees fleeing war and conflict.

For the IHI, this topic is something they’d like to include in future curricula. “How these military interventions affected migration are rarely studied,” Lu explained. “Particularly our refugees from these places that have been very much devastated by war and other forces. And so, when we look at the Southeast Asian population, there is a large percentage that came to the US during this time.”

Lu continued, “The AAPI community is treated as this monolithic story while these numbers cover the real story behind how people come to this country without any wealth or resources. There are huge income disparities and huge differences in experiences across the AAPI community.”

Another dimension to consider in the conversations of race and migration is gender. Subsequently, Asian American women suffer a double burden of discrimination. Lu is also an immigration attorney outside of the IHI. She cited the Atlanta shootings, and how it triggered many of her clients who had been in similar situations.

“You can clearly see how these intersectional prejudices against Asian American women so often lead to sexual violence,” Lu said. “This is directly tied to the US military occupation of bases in Asian countries where this theme of conquest very often crosses over into sexual conquest as well.”

Climate change has already raised questions about climate refugees. Wang and Lu were asked what projections for this future would look like—and if it would change what society thinks about migration.

“My hope is that it would change the way people talk about migration and race because we know that climate change is going to affect everybody,” Lu said. “It’s not only going to affect some people. However, my fear is that it will not really change anything because of the way that climate change works. It affects certain populations more than others and it is very much dependent on that community’s level of privilege.”

Wang, who has also done some legal work with climate justice, added that the problematic narratives of the perceived ‘global south’ and ‘global north’ need to change. To her, climate justice is very much about racial justice. And at the heart of that is how migration can be recast and talked about.

“Climate change is happening whether or not you accept it,” Wang said. “We need to think about how we can protect and preserve our futures. I think something more fundamental and structural is needed for us to be equipped in thinking about climate migration as an inevitable, global phenomenon.”

The Immigrant History Initiative is committed to sharing the intersectional diversities of all the communities within the United States. As they continue to work with educators and activists to develop complete narratives, consider supporting their work here.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story or making a contribution.