By Defang Zhang, Ilena Peng, Chuqin Jiang and Vera Shang

Former residents like Julie Chen, a 27-year-old Chinese American, have fond memories of growing up in Manhattan and are still regularly in the area, but have both since moved to other New York City boroughs.

Chen, who was born in Manhattan’s Chinatown, grew up in the area until moving to Elmhurst, Queens with her parents in 2012.

“Growing up in Chinatown was my youth,” Chen said.

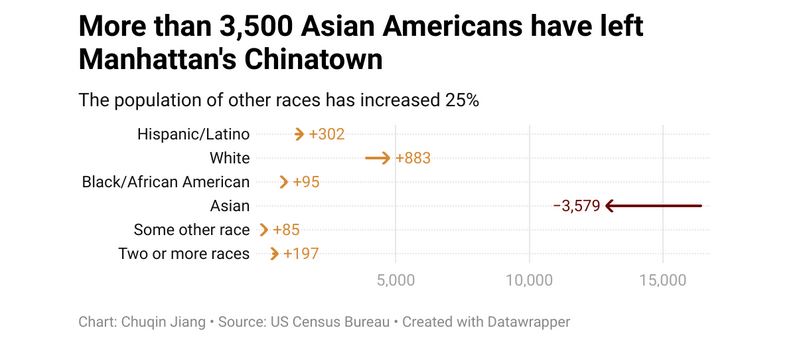

Chen and her family are among the over 3,500 Asian residents who have moved out of the three Census tracts that made up the bulk of Manhattan’s Chinatown in the past decade, according to the 2020 Census. The area is about 63% Asian, compared to nearly 73% Asian in the 2010 Census.

The area has seen losses in total population as well. But in all three Census tracts, the decrease in Asian population outpaced the decrease in total population. In Census tract 41, an area bordered by Bowery and Centre Streets that also covers Little Italy, the total population fell by 3.76%, while the Asian population fell 23.43%.

This decrease in Chinatown’s Asian population is occurring amid a period of growth in New York’s Asian population otherwise — Manhattan’s Asian population increased by 23% from 2010 to 2020. New York State’s population increased by 36%.

Victoria Lee, the co-founder of Welcome to Chinatown which is a local non-profit organization rooted in Chinatown, said some younger Asian Americans are now opting for apartments elsewhere that offer more amenities at a similar or lower price, instead of trying to afford rent in Chinatown’s newly developed high-end buildings.

“I have friends who have moved out. It’s not because of the extreme circumstances, but it’s more about choosing for their quality of life. They wanted to have more space,” Lee said. “They feel like their money goes farther out of outer boroughs than it does in Chinatown.”

Chen would agree with that.

“Vegetables [in Chinatown] are more expensive than the vegetables I find in Elmhurst,” said Chen of a recent grocery trip. “We have like two Chinese supermarkets here, two or three. And they’re all cheaper relative to Chinatown.”

Karen Kostiw, a real estate salesperson at Warburg Realty, said Brooklyn, New Jersey, and areas of Queens, like Long Island City, have become popular destinations for those moving out of Chinatown and the Lower East Side

“The further out you go, the more space you’re going to be able to get,” said Kostiw, who did not comment on specific populations within Chinatown and the Lower East Side to not violate the Fair Housing Act.

New developments like One Manhattan Square, the first of four new planned luxury towers, will change the area’s landscape, Kostiw said. The building and its million-dollar apartments have drawn widespread criticism from residents of color in the area.

But Kostiw said increased green spaces and other ongoing projects like Essex Crossing, which aims to offer affordable housing and retail spaces for local businesses, might help maintain a sense of community even in a gentrifying area.

“We’re trying to retain the historic districts. You can even see [that] little Italy and some of those other areas, they did get smaller over time,” Kostiw said. “But I think what creates a draw to Manhattan [is] having some of these wonderful areas and places to go. There are a lot of people working to maintain that culture and livelihood.”

Despite those efforts, many former residents say they aren’t seeing the results.

Growing up in Manhattan’s Chinatown, 21-year-old Ricky Yang and his family resided in the area for more than two decades. Yang said gentrification in the area has led Chinatown to lose some of its small businesses and their innate character.

“As the neighborhood gets more and more gentrified, you’re going to kind of lose a lot of that authenticity,” Yang said. “Chinatown ten years ago looked completely different from Chinatown now. It sucks. I would prefer Chinatown to be as it was a long time ago.”

Though Yang now lives in Park Slope, a neighborhood in Brooklyn, he remains rooted in Chinatown. He is a member of Protect Chinatown, a local advocacy group aiming to provide safety measures against anti-Asian hate crimes. He has also opened two restaurants in the area: The Dough Club and Taiyaki NYC, both located in the heart of Chinatown.

“Being able to have a store here that represents Asian culture and Asian values, it was kind of our way of bringing back some of that — like reverse gentrification,” Yang said.

The neighborhood was historically built upon locally owned businesses. For Yang, having a locally owned business is part of maintaining the area’s cultural identity.

Nelson Mar, a lawyer in Manhattan’s Chinatown and the president of 318 Restaurant Workers Union, said displacement might be another driving force behind this demographic shift.

“The pressures that real estate developers are putting on, both residential and commercial tenants, it’s causing rents to go up for both residents and for small businesses,” Mar said.

He explained that Chinatown is a hub for many Chinese immigrants since they can navigate the community by shopping in Chinese grocery stores and services that were tailored for their culture.

“Over the last few years, given all the pressures on the commercial tenants, a lot of those small mom-and-pops, which basically were the ones that were serving the Chinese immigrant community, a lot of them had to close,” Mar said. “You can see a lot of ‘For Rent’ signs all over the storefronts.”

Mar explained that rising land prices in Manhattan lead to an influx of luxury stores and buildings into Chinatown, leaving family-owned small businesses unable to stay open, eventually driving people away from the community.

“Even if you can afford to live there, if you have a rent-stabilized apartment, you can’t afford to actually shop [in Chinatown],” said Mar.

Methodology

We selected the census tracts for Manhattan’s Chinatown — tracts 16, 29 and 41 — based on Statistical Atlas. To look at the change in the Asian population in these census tracts, we looked at redistricting data from the 2010 and 2020 decennial censuses. Because tract 29 was split into 29.01 and 29.02 in the 2020 Census, we added counts from tracts 29.01 and 29.02 to draw comparisons between the 2010 and 2020 Census. Our analysis of geographic mobility was based on American Community Survey data from 2010 to 2019, using data from table B07204_001E.

All data and analysis for this project can be found on GitHub.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a contribution.