By Raymond Douglas Chong, AsAmNews Staff Writer

Hundreds of families and individuals sleep in safe, clean, affordable homes in neighborhoods around Little Tokyo of Los Angeles. Hundreds of economically insecure families and seniors receive assistance from a non-profit social service agency in Little Tokyo. And hundreds of Asian youths from the greater Los Angeles area participate in sports in a newly built sports and activity center on Los Angeles Street in Little Tokyo.

They all can thank “The Worst Boss in the World.” The worst boss set a meandering path for a pious man to discover his passion and placed him in a position to alter the development course of one historical neighborhood in Los Angeles.

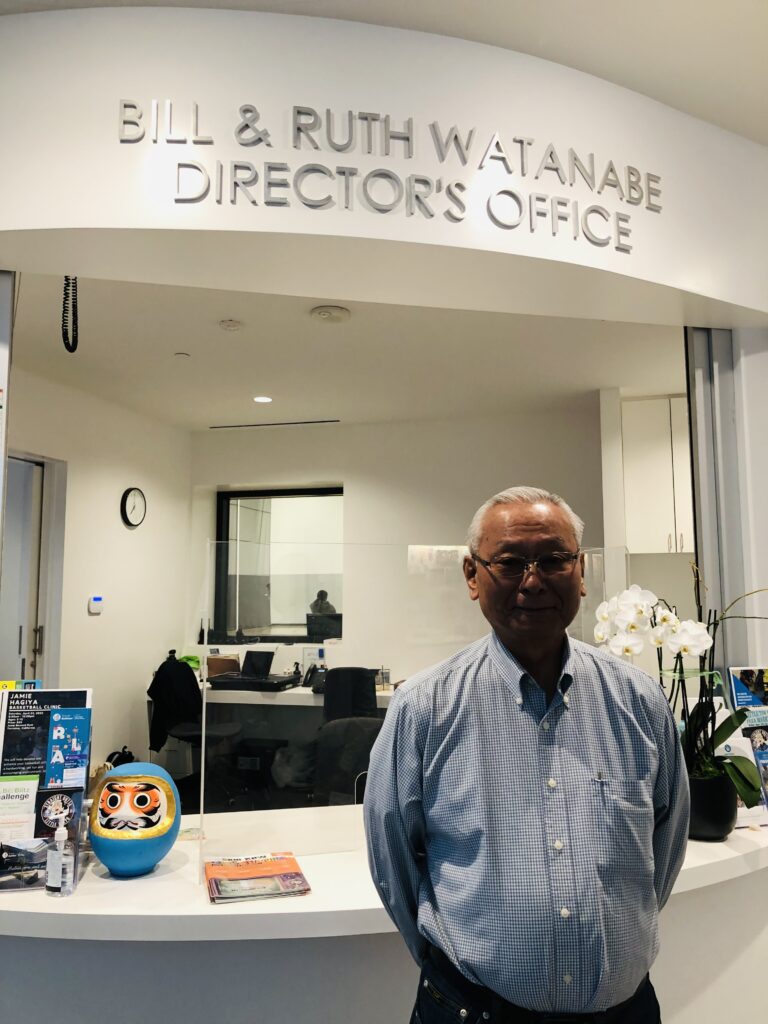

Our man is Bill Yoshiyuki Watanabe. He humbly served the Nikkei community of Little Tokyo in Los Angeles for much of his working life. He is widely recognized as a visionary leader and community servant, serving as the founding Executive Director of Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC).

During his LTSC tenure, Watanabe strived to preserve the Japanese American heritage of Little Tokyo, provide social services and affordable housing, and other amenities to the Japanese American community of the Southland, and help disadvantaged peoples of color in LTSC’s neighborhoods.

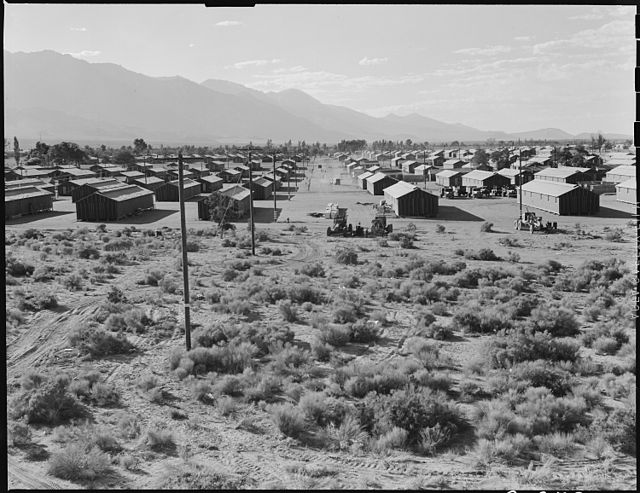

Manzanar Concentration Camp (1944 to 1946)

Watanabe, a second-generation Japanese American or Nisei, had four siblings, Kinichi, Kinjiro, Takeshi, and Yoshimichi. Rokuro Watanabe, his father, and Katsuye Watanabe, his mother, raised him under challenging conditions.

Before the war, his father was farming leased land in Sun Valley. He built two homes on a packing shed for the flowers.

During World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which evacuated over 120,000 Japanese American citizens and Japanese immigrants on the West Coast. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) confined them in isolated, fenced, and guarded concentration camps. The WRA forcibly relocated all Japanese to concentration camps inland. Little Tokyo became a ghost town.

Watanabe mused: I was born in Manzanar Concentration Camp on January 5, 1944. So I have no recollections of the Concentration Camp experience, although my older brothers were old enough. My family was extremely fortunate to have a kind and honest landlord. The white landlord promised to look after the farm until the war ended and even visited the family on several occasions while at Manzanar!

Manzanar is at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in the Owens Valley of California. WRA imprisoned 11,070 people at Manzanar, mainly from the Southland. Under harsh and crowded conditions, they lived within a 540-acre housing section of 36 blocks. Military police operated eight guard towers. They patrolled the camp’s barbed-wire perimeter fence. People crowded into barrack apartments, ate in communal mess halls, washed their clothes in public laundry rooms, and shared latrines and showers with almost no privacy.

Recovery in the Southland (1946 to 1965)

After the end of World War II, in 1946, the Watanabe family returned to their home on the flowers farm in the San Fernando Valley. Watanabe reluctantly attended Japanese language school on Sundays.

At 14 years old, he became a Christian. He remembered: I became a “born-again Christian” at 14 while attending a Japanese American Christian church. I had a religious epiphany. God opened the door for me to become a professionally trained social worker and serve Southern California’s Japanese American and Asian American communities.

During junior high school and senior high school, he participated in gymnastics. In 1961, Watanabe graduated from San Fernando High School.

The Watanabe family visited Little Tokyo during weekends. Founded in 1884, Little Tokyo, a Japantown near Los Angeles City Hall, is the heart of the Nikkei community in the Southland. At its peak, about 35,000 lived in this thriving neighborhood, the largest Japantown in the US. Now, about 1,000 Japanese, primarily seniors, live in Little Tokyo.

Watanabe recalled Little Tokyo:

But my parents did visit Little Tokyo at least once a month, drive in and do some shopping. We would eat at a restaurant maybe, then go home.

I remember one of my early recollections: a few times, I can remember seeing streetcars, and so they were going up and down First Street, and people would wait for them right in the middle of the street. There would be a small island. I thought, wow, because you never saw anything like that in the valley.

It was a little seedy in the city. And the city was different from the farm.

It was always like an adventure, something different. My father would get a haircut at the barbershop here, so my brother and I, of course, had gotten bored, and we were running around, but it was right here on San Pedro Street in the Firm Building, which Little Tokyo Service Center now owns. But we would go there and get a haircut, and he would talk to his friends. The barber would know each other for many, many years.

So that kind of thing, and then go shopping at the Asahi Shoe Store or pick up a shirt or something, then go to the grocery store and pick up food. And then it would be dark, and we have dinner somewhere; then we’d make our way back home. So that was probably at least a monthly trip.

Wandering Years (1966 to 1979)

Watanabe attended San Fernando Valley State College in Northridge. In January 1966, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering.

He joined Lockheed Missile & Space Division near Moffett Field in Sunnyvale. During the Cold War, Lockheed was building missiles against the Soviet Union. He deferred the military draft as a college student and critical worker in the defense industry.

Watanabe realized:

After one month of working as an engineer, I realized I was not a good engineer, and I just did it because I could not think of what else to do. But I knew I was not a good engineer, and I would never be a good engineer. I could be, at best, a mediocre engineer, but that was not attractive to me.

After a few months on the job, I realized I was not cut out to be an engineer and was desperate to “find my passion,” but I had no idea what that could be. I was a Christian from my youth, and I realized that I had chosen to go into engineering strictly as a matter of practicality.

After he left Lockheed, Watanabe explored his Japanese roots. In September 1967, he attended the prestigious Waseda University in Tokyo. Kokusaibu, Waseda University’s International Division. With Kokusaibu, American students experienced the Japanese language and culture in the classroom, around the city, and across the country for a year.

He returned to the United States to ponder: I was soul-searching, meditating, and praying about what I should do with my life. To earn some money in the meantime, I applied for a job with the City of Los Angeles. He worked as a junior engineer for the City of Los Angeles in the Department of Engineering/Public Buildings from December 1968 to September 1970.

I kept waiting for the day I could quit the job and leave. My boss was so horrible that my blood pressure shot up by 40 points, and I got rejected when I reported for the Army draft physical! Finally, I left the City and ended the worst 18 months of my life — and then began the best time of my life as a social worker in Little Tokyo, which turned out to be my life’s passion!

While working for the City, he took night classes at California State University, Northridge, in social work. While walking to his car after class, he encountered his professor. During the chat, the professor suggested that he apply to the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Social Welfare since the school was seeking students of diverse backgrounds. The professor offered to help him get into the program. Watanabe took this as a sign from God that he should be in social work. He started in October 1970 and graduated in June 1972 with a master’s degree in Social Welfare.

From 1972 to 1978, he was involved with an urban Asian American Christian commune, Agape Fellowship, in Echo Park of Los Angeles. About 30 young Christians formed a collective like the first-Century church immediately following the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. . On the West Coast, the Jesus movement was a generational backlash against the rigid Christian doctrine.

From 1977, Watanabe worked at the Japanese Community Pioneer Center in Little Tokyo to earn money for Agape Fellowship. He coordinated welfare services for Japanese-speaking seniors.

Little Tokyo Service Center (1979 to 2012)

After leaving Agape Fellowship and working for the Pioneer Center, Watanabe helped the incorporation and beginning of the Little Tokyo Service Center, a non-profit organization, in 1979. The Board of Directors hired him as the founding Executive Director of LTSC in January 1980. He and the pioneer staff (Yasuko Sakamoto and Evelyn Yoshimura) worked at Japanese American Cultural & Community Center offices. Little Tokyo is one of three remaining Japantowns in the United States.

Watanabe recalled that:

We needed a program that could serve everybody, so that is how LTSC started. The goal was to establish a one-stop, multi-purpose social service agency. At that time, the only community service providers in the Nikkei community were those aiding Japanese seniors.

I had great faith that God had led me to social work, so I was confident that God would provide for me if I remained faithful to that calling. I prayed to God for wisdom and guidance for almost all my career decisions. I helped start the Little Tokyo Service Center in 1979. This was the next step in my career as a social worker and community organizer. Of course, the main challenges in starting a new nonprofit organization are funding and how to build the structure that would ensure a viable program for the long haul.

During the early years, LTSC mainly served Japanese American seniors in this enclave of about 3,500 residents. The changing demographics in Little Tokyo have resulted in an ethnically diverse community with an aging population. The plurality of Little Tokyo residents is Asian; Blacks represent the second largest demographic group, followed by Hispanics. In 2010, Asians accounted for almost 40 percent of Little Tokyo residents.

He envisioned providing basic human needs for limited English-speaking Japanese seniors in Little Tokyo. Then his vision grew to develop a multi-purpose agency that could address the unmet needs of the broader Japanese American community, revitalize and preserve Little Tokyo, and collaborate to help other low-income neighborhoods in need throughout Los Angeles. LTSC promoted the economic revitalization of Little Tokyo while preserving Little Tokyo’s history and culture.

By 2012, Watanabe had developed an array of programs for Little Tokyo: Child Development, Family Services, Youth Services, Senior Services, Affordable Housing (13 properties with 600 units), Small Business, and Discovery Center. He led LTSC to build Casa Heiwa, apartments for very low income disabled, seniors, and working families. He guided the renovation of the Union Center for the Arts, home of the East West Players, and the landmark Far East building, with its iconic CHOP SUEY neon sign.

On Saturday, March 12, 2022, Watanabe proudly joined the grand opening of Terasaki Budokan, a Little Tokyo Service Center community recreation facility. It represented a culmination of his 30-year dream and perseverance that brought the vision to life.

Lastly, one project that stands out for me is the construction of the Terasaki Budokan, a multi-purpose sports and activity center that held its Grand Opening on March 12, 2022. The Budokan took 28 years of effort. I am confident the facility will be crucial for ensuring the future survival of the historic Little Tokyo neighborhood.

In 2012, Watanabe retired from LTSC.

Epilogue (2012 to now)

After a decade, Watanabe constantly remains busy in the Little Tokyo community, even as a tour guide. He enjoys the golden retirement with Ruth, his wife, and Natalie, his daughter. He lives in Silverlake near downtown Los Angeles. For leisure, he enjoys trout fishing, Trivial Pursuit game, and Star Trek television series and motion pictures.

I believe if each of us does our part for social justice, even if it is a small part, it can add up like drops of rain becoming a mighty river.

“The Worst Boss in the World” made it possible for a man to be placed in a position to provide for the community’s needs.

From Manzanar Concentration Camp, Bill Yoshiyuki Watanabe, a faithful servant of God, is a towering legend with Little Tokyo and in the Southland, for the next generations.

AsAmNews is incorporated in the state of California as Asian American Media, Inc, a non-profit with 501c3 status. Check out our Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a tax-deductible financial contribution. We are committed to the highest ethical standards in journalism. Please report any typos or errors to info at AsAmNews dot com.