By Jessica Xiao, AsAmNews Staff Writer

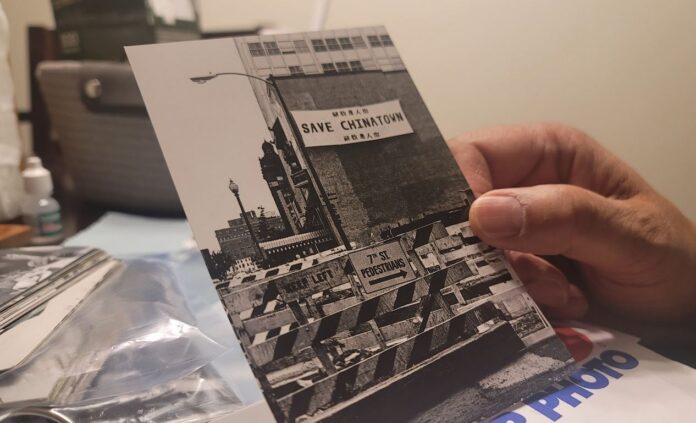

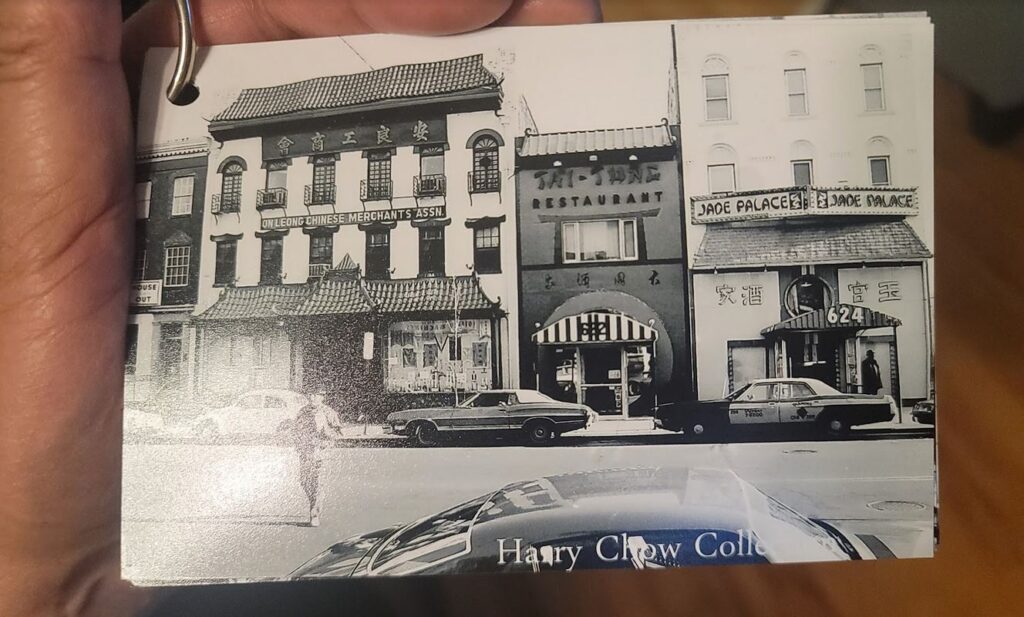

CHINATOWN, WASHINGTON, DC — Girls jumping rope. Unmarried older Chinese men standing around on the block. Neighbors visiting the Chinese herbal medicine shop. These are the scenes of everyday life that DC-born Harry Chow captured in the Chinatown he knew in Washington, DC.

Born and raised in the DC-metropolitan area, Chow and his parents lived in Columbia Heights, a neighborhood north of Chinatown, but he worked every summer in the laundromat his parents owned in Chinatown in the 1940s-50s. He briefly moved to Chinatown, and worked for DC Recreation and became involved in Chinatown youth programs after graduating from high school. All throughout his life, he took photos of daily life in Chinatown.

“In the mid-1960s, they passed the immigration law – more immigrants came in ’68, ’69, early 70s. A lot of Chinese were coming into Chinatown.”

That Chinatown no longer exists. Although the neighborhood today is listed by Rent.com as one of DC’s most popular, it is filled with luxury condo developments and empty storefronts, long devoid of the daily life of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans that once filled its streets.

According to DC’s 2008 Chinatown Cultural Development Small Area Plan, in 1970 Chinatown had 3,000 residents. In 2008, only 300 Chinese American residents remained. Just 18 percent of DC’s Chinatown residents today identify as Asian American. After a metro stop was built in 1976, the first convention center in 1982, and an entertainment and sports complex in 1997, Chinatown today bears few Chinese elements beyond a few surviving restaurants and architectural designs.

“All the businessmen in Chinatown wanted [the convention center and the sports center] – they thought they would thrive because tourists would come in,” Chow recalled. “I talked to one guy who used to live [in Chinatown]. They offered him so much money, he would be a fool to not accept it because they could send their kids to college and buy a house in the suburbs and go on vacation.”

Today, most Chinese Americans live in Montgomery County, Maryland, or in Virginia. And to find Chinese ingredients and groceries, any remaining Chinese DC residents have to travel to Maryland or Virginia. Chinese residents of the former Chinatown live mainly in two apartment complexes: Museum Square and Wah Luck House, the last vestiges of Section 8 affordable housing in the area.

Although Chinatown today may be unrecognizable from its most vibrant days, tenants of both have fought to remain in the neighborhood they consider home.

Wah Luck House was built to house Chinatown community members displaced by the construction of the first convention center in 1982. When the owner decided to sell, the tenants purchased the building with the D.C Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) by forming the Wah Luck House Preservation LLC in 2017.

Museum Square tenants, mostly African American and Chinese residents, faced displacement when the owner, Bush Companies, wanted to demolish the building in 2015 to build two new luxury apartment and condo buildings. As per TOPA, the building was offered for sale to residents, but at a hefty price of $250 million – or $800,000 per unit – an unattainable sum for low-income residents. Tenants sued Bush Companies, which claimed that was a reasonable valuation. The tenants won initially and in an appeals court. Given the development of new luxury condo buildings in the same neighborhood, it is only likely the valuation would continue to increase. No news updates have been published since 2017. It appears to still be in litigation.

What happened to DC’s Chinatown?

The first Chinese immigrants arrived in DC in 1851. Thirty years later, they settled in a neighborhood today known as Federal Triangle, south of Pennsylvania Avenue. They were displaced in the 1930s when the federal government decided to build several government buildings in the area.

The On Leong Merchants Association, a prominent tong society, moved to a new headquarters on H Street, a neighborhood that was predominantly German. Tongs, although sometimes associated with criminal activity, were primarily formed by Chinese immigrants as mutual aid networks providing services to fellow Chinese immigrants, especially in the face of systemic discrimination, language barriers, and racism. This neighborhood between 5th and 8th Streets and H and I Streets is where Chinatown is today. It’s also the Chinatown depicted in Harry Chow’s photos.

The Capital One Arena

Different former residents have differing theories on Chinatown’s downfall, but all of them are economic and related to the development of the sports/entertainment complex formerly known as both MCI Center and Verizon Center, and now as the Capital One Arena. It broke ground in October 1995 and was completed in December 1997.

“To live in DC and watch it degrade and not have any say in how things turn out is very disappointing,” says Richard Wong, former Chinatown resident who has seen it decline over the years and recalls going to meetings about the stadium development with other Chinatown leaders and business owners. He is currently a volunteer with several community organizations including the 1882 Foundation, a community organization that convenes around storytelling, building cultural awareness, and preservation of Chinese American culture.

Wong’s parents were Chinese immigrants who came over in the 1940s-50s. He was born in the US, grew up in New York, and went to the University of Maryland. He decided to stay and he became an economist who worked at various government agencies. But outside of his day job, he became a leader at the On Leong Merchant Association and other Chinatown community organizations.

“I can go to any Chinatown on this earth and feel like I was home. Chinatown is home no matter where I am,” said Wong.

His family has been associated with Tongs for many generations, so it felt like a natural pathway for Wong. His grandfather was president of a family association in Boston. His uncle was president of a New York branch and the national chairman.

According to Wong, many businesses closed after 1997 and didn’t have the chance to recover. Restaurants were bought out and overtaken by big box restaurants where the only Chinese characteristic about them was the name of the establishment written in Chinese characters below their English sign. Then, when even the corporate restaurants moved out during the COVID-19 pandemic, they left shopfronts empty.

The developers also made empty promises, Wong said. The Gallery Place mall, which connects to the stadium, was supposed to be extended from 6th St to 7th Street so that the Chinese businesses at the time could be located in the mall. Chinatown businesses invested, but the developers ran out of money and filed for bankruptcy. The mall was never fully completed, and many of the Chinese businesses couldn’t survive. In 2014, the remaining developers involved in the project sold their stakes, without being held to account for their promises. The mall has also declined since the pandemic and is now underutilized. It housed a bowling alley that shut down during the pandemic, and the Regal Theater in the mall just closed earlier this year.

“The demographic of the stadium-goers is different from the demographic with demand for the local businesses [in Chinatown],” says Wong. “All of those restaurants came into Chinatown and have left Chinatown. Those storefronts were American businesses – Fuddruckers, Panera Bread, and so on. Now they’re gone because the only foot traffic is from sporting events or the use of the stadium so they didn’t survive the pandemic.”

Promises were made to residents and businesses, but many say those promises were broken.

“Contracts were never written down on paper. They were word of mouth. Promises were nothing without a signed contract. Those signed contracts never surfaced,” said Penny Lee, a Chinatown documentarian who lives in Montgomery County.

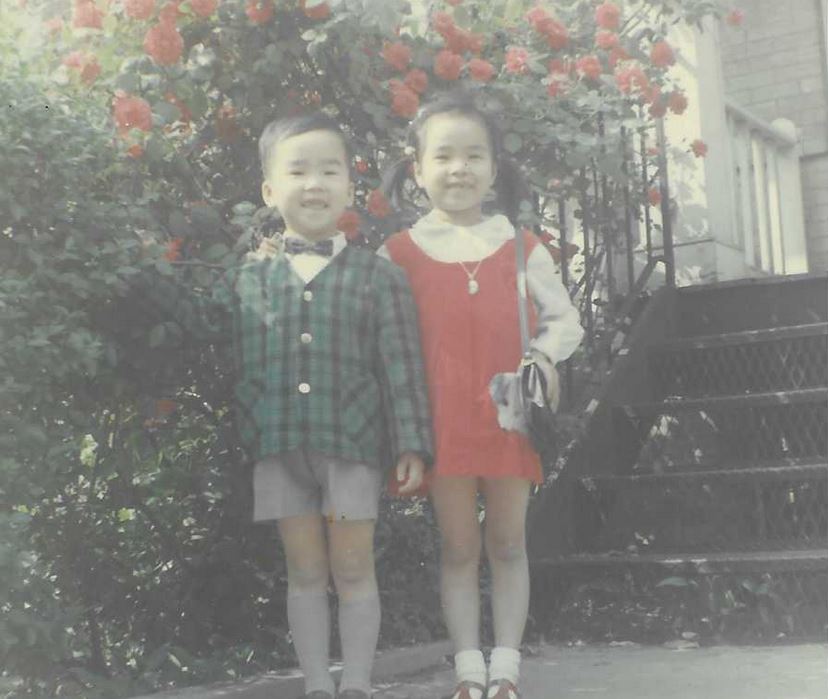

Penny Lee and her family moved to the US in 1967. Her dad opened a Chinese restaurant first in Columbia, South Carolina, and then relocated to Charlotte, North Carolina. Every summer she’d visit her great-grandmother in Chinatown, Washington, DC, and participate in the DC Rec programs.

At the time, she had a lot of friends in Chinatown, which was booming with young energy. A wave of Chinese families immigrated to the US from Hong Kong or Southern China in the 1970s after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (aka the Hart-Celler Act) abolished a racist quota system from U.S. immigration policy.

Lee saw many Chinatown residents’ homes bought out to make room for new development, including her own aunt’s home. Many residents couldn’t afford to stay and realize the new values of their homes because they couldn’t pay the increased property taxes. They felt they had no choice but to sell.

Lee believes that at the time of the stadium, DC had a lack of advocacy and lack of organized groups who could speak for the Chinese and Chinese American population.

“I was so young that elders would’ve looked at me like, ‘What are you talking about?’ A lot of the leadership at the time didn’t feel like their voices mattered. ‘We’re in the nation’s capital’ and Chinatown has been a small, secluded area – the leadership didn’t want to cause trouble or anger the government. There was a lot of fear and mistrust, and still, discrimination,” said Lee.

Today, she is a professional video editor. Lee uses her skills also to document the history of Chinatowns. “[A] passion I have is preserving stories – stories of DC Chinatown because every time my friends get together at funerals, weddings, baby showers, we always talk about growing up in Chinatown, what it was like back then. A lot of them don’t live in Chinatown anymore, they live in the suburbs. All those stories I felt would be lost because they weren’t being preserved or shared. I thought to myself, let me do a film and interview my friends and people I know born and raised in Chinatown, so they can retell their stories and recollections of what it was like.”

She’s produced three documentaries on Chinatowns. “Flashback,” her latest project in collaboration with the 1882 Foundation, features short oral histories of DC’s Chinatown.

DC Chinatown is a warning sign for Philadelphia as history continues to repeat itself

In July 2022, the 76ers proposed building a stadium in a mall in the Fashion District bordering Chinatown, Philadelphia. The team has a lease at Wells Fargo Center owned by Comcast, which just underwent a $400 million renovation, that ends in 2031. The development which will cost an estimated $1.3 billion is privately funded, although it would benefit from city subsidies for its proposed location in the Fashion District Mall.

This is not the first time the existence of Chinatown, Philadelphia, has been threatened—In 2003, a baseball stadium was proposed. In 2008, a casino was proposed. Philly advocates successfully fought them off. However, they were not able to fight off Vine Street Expressway, which split Chinatown in half, or a convention center that now borders Chinatown.

Debbie Wei, founder of Asian Americans United, one of the organizations central in fighting the current stadium proposal, and a local organizer for over 40 years, has seen it all and been on the forefront of many of these fights to preserve Chinatown, Philadelphia.

“What proposed development projects like the 76ers arena ignore is the unique and historic nature of our ethnic enclaves. Chinatowns have existed across the United States for nearly 200 years, created out of necessity by Chinese immigrants who retreated into self-contained districts in search of safety from the beatings, lynchings and massacres that were often their lot in the highly segregated cities of our nation’s past. Excluded from most jobs as a threat to White laborers, the Chinese undertook “women’s work” — running laundries and providing food service — to survive. From the fruits of this bitter history, Chinese Americans slowly fashioned a life and a future as part of the diverse American tapestry. Chinatowns became havens of linguistic and cultural security and familiarity,” Wei wrote in August last year for the Washington Post.

In 2009, in opposition to the proposed Foxwoods Casino in Chinatown, Wei told NPR, “Two hundred families have lost their homes. We lost like a third of our housing, a third to a half of the housing. It’s – you know, it’s a small community and you can only take so much. So, between the Vine Street Expressway and Convention Center and the Independence Rail Tunnel and the Gallery and the Greyhound Bus Station, you know, like enough is enough.”

Yet, nearly 15 years later, Philadelphia, Chinatown, continues to have to fight for every inch. Earlier this month, a coalition of Chinatown business and community leaders officially announced their opposition to the stadium.

In fall of last year, Wei and other Philadelphia Chinatown advocates brought Councilman Squilla to Washington, DC, and DC’s Chinatown community leaders gave them a tour. One resulting collaboration was a joint op-ed about the dangers of a stadium on preserving the heritage and homes of the Chinese community.

“We watched as these developments and promises led to the destruction of the community we once loved,” said a DC Chinatown leader. “Learn from our experience. Don’t make the same mistake. Do all you can to save Chinatown, and do not trust empty promises.”

Stadiums and Gentrification are a major threat to Chinatowns and other ethnic enclaves

Alex Peng, sportswriter for the World Journal, the largest Chinese language newspaper in the US, has observed how stadiums have affected different cities across America over time. “If you look at the history of sports stadiums, you will find that most of the teams cannot get funding from tax players, but still have a tremendous negative impact on regional and local development. Even if they don’t use public money, they have a detriment to local community.”

And as Wei notes in a recent op-ed for the Washington Post, “Chinatowns across the country have been decimated by sports arenas: the Kingdome in Seattle, Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, the Capital One Arena in D.C.”

The Chinatown in St. Louis was demolished to make way for the Busch Memorial Stadium. Seattle’s Chinatown, officially called the International District, was partly destroyed by the construction of a highway in the 1960s, and boxed in by the Kingdome Stadium. Asian American protestors disrupted the groundbreaking of the stadium – and held a larger demonstration two weeks later, leading to more funding for housing and increased Asian American community involvement in any developments in the International District.

“If we look back, we understand what we’re talking about. People worry such a big facility is going to kick everyone out because of the cost of land, but it’s not only that—it’s gentrification, because who was actually benefiting? Big companies. Only they have the money to play with and invest,” says Peng.

And ultimately, the benefits accrue to the developers, not to the community or the city. And the developers have become billionaires through less than morally upstanding means.

David Adelman, the billionaire developer leading the 76ers stadium project alongside the 76ers’ owners Josh Harris and David Blitzer, is the CEO of Campus Apartments, which has made its profits gentrifying college neighborhoods to build student housing, notably around DC’s Howard University and Philly’s University of Pennsylvania, displacing Black working-class populations.

David Blitzer is an executive at Blackstone Group, a firm that was singly named in a statement by UN experts condemning its “egregious business practices” and its impact on human rights, while Josh Harris is co-founder of Apollo Global Management, which has been linked to sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Wong cautions Philadelphia to not believe the promises of the developers. Although they promote job creation and economic opportunity in order to sell their vision, they don’t care about the neighborhood. “Monumental Sports, which runs [Capital One Arena] doesn’t care about the neighborhood.”

“The model doesn’t work, yet it continues to be the reason for more development. Restaurants, sports centers, convention centers do not bring in a regular flow of consumers. Residents do. Without residential properties and especially lower-income units there will not be a stable community in DC. Residents bring and support the need for more restaurants and infrastructure; not the other way around,” Wong added.

The Future of DC Chinatown

As for DC Chinatown? Some are skeptical.

“It takes a miracle to revive. If the government wanted to help us preserve this neighborhood, they would’ve done it years ago and offered tax breaks to residents still living there, but that never happened,” says Lee.

But DC’s Chinese Americans have not given up. 1882 Foundation and others have plans to build back Chinatown—which they believe is more about the special qualities that emerge from community cohesion than it is about a few blocks of geographical space. In 2021, the 1882 Foundation received a $500,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon foundation to support “transformation of the 1882 Foundation’s Chinatown headquarters into a story center and social workspace that will welcome allied non-profit Asian American and Pacific Islander organizations and partners in the Washington, D.C., area.”

In an 1882 Foundation statement, they dismiss the idea that DC Chinatown is dead.

“For decades, we’ve been inundated by speculations about D.C.’s Chinatown future by outsiders that have centered a narrative of a ‘dying Chinatown.’ It seems like every ten years, a newspaper article is written about the shrinking of our community. We have been here, we will always be here, and we are proud to be given the opportunity to enable greater visibility of the work we and our community of storytellers, educators, and culture-bearers do to support the Asian American and Pacific Islander community.”

Regardless of what DC Chinatown looks like in the future, it is certain that Chinese communities and advocates like Debbie Wei will continue to fight for their right to exist:

“Communities like Chinatown, built on the relationships and memories created there, nurture a commitment to cities that spans generations. When you attack the fragile ecosystem of urban life and disrupt that commitment, and destroy the diversity that is a hallmark of thriving cities, there is no going back. That is why we say no to this arena, and why we will fight, yet again, for Chinatown’s right to exist.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.