By John Faye

Can you stand at the intersection of two heritages and not feel particularly connected to either?

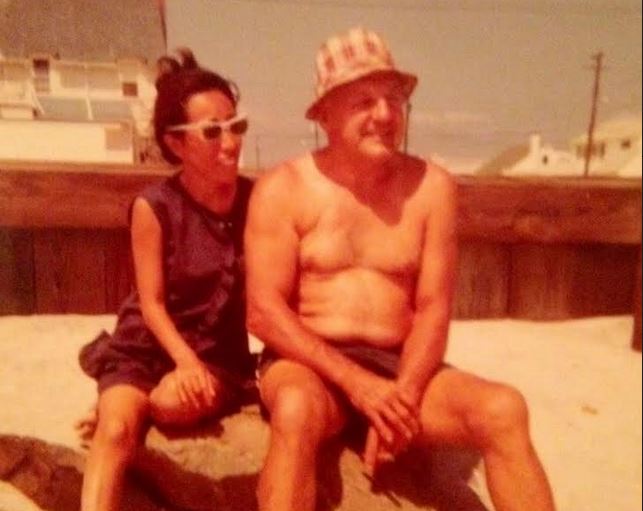

That was my reality as a boy growing up in Delaware in the 1970s, the unlikely

lovechild of a 62-year-old Irish father and a 40-year-old Korean mother. At that time, I was a long way from becoming the lead singer of the alternative rock band The Caulfields, and being one of the only mixed-race Asian American frontmen to sign a major label record contract in the 1990s.

Instead, in the 1970s, in terms of heritage, I was unmoored. Culturally adrift.

Was I Irish? Yes, but I didn’t feel Irish. Was I Korean? Yes, but I didn’t feel Korean. I

definitely was American, born in Philadelphia, and so for a while I saw myself as just like any other American kid. I loved apple pie as much as anybody, I can tell you that.

But with things being as they were in the era just after the Vietnam War, enough

ignorant people planted enough seeds of doubt in me to convince me that I was

different, and not yet in a good way.

Case in point: One time I attended a Sunday brunch with a friend’s family when the

friend’s grandmother turned to me and offhandedly asked, “So… What part of China are you from?”

After an uncomfortable pause, I mumbled with a mouth full of eggs, “I’m from

America.”

I didn’t correct her presumption of my being Chinese.

This was a tactic I came to use a lot whenever people asked me “where I was from.”

Even if they were genuinely curious about my background, I always viewed this line of questioning as suspect, an attempt to paint me as the alien I already felt I was.

And often things would veer from microaggressive to downright hostile. As a boy, I endured my share of bullying, including racist taunts that exposed ignorance and

disregard for which Asian country my mother’s side of the family came from.

These bullies clearly had no desire, and perhaps no ability, to distinguish among Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or any other Asian heritage.

To be honest, though, I wasn’t making a lot of distinctions in those days myself.

Lack of Asian Influences

When I wrote my memoir, The Yin and the Yang of It All: Rock ‘N’ Roll Memories from the Cusp, as Told By a Mixed-Up, Mixed-Race Kid, I started the book by noting that my childhood might have benefited from some of the Asian representation that came much later––K-Pop, Pokemon, Squid Game, Kim’s Convenience.

The country also hadn’t yet declared an entire month—May—as Asian American and Pacific Islander Month, nor were Asian Americans the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the United States, as we are today.

Instead, around the time of the bicentennial, America had nothing that would make growing up Asian, or even part Asian, seem remotely appealing.

And Irish-Korean? That there was a real conundrum.

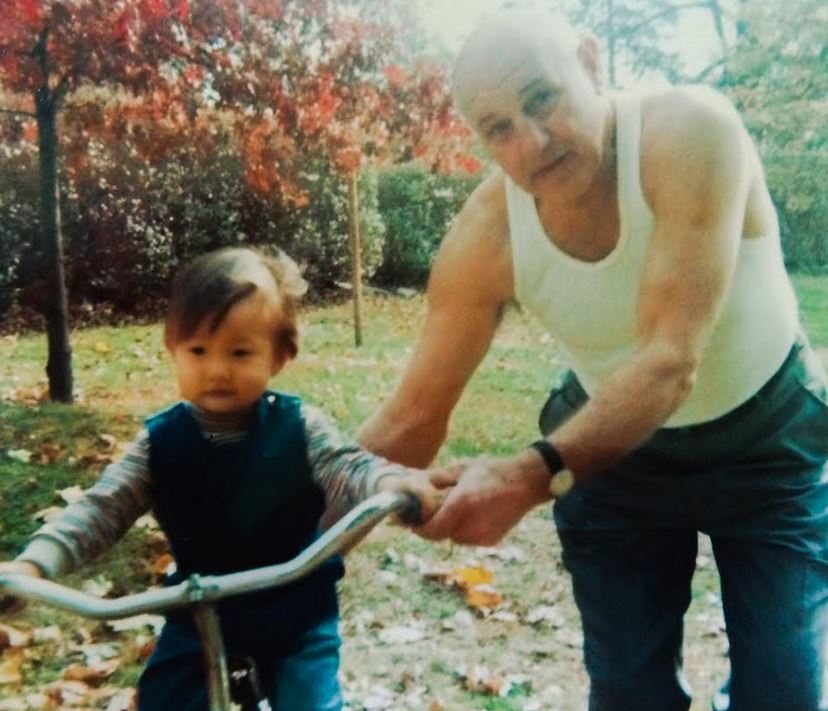

My search for an elusive mixed identity was derailed after my father died of cancer

when I was 6. That left my mother to raise me on her own, along with my three older half-sisters.

Exposure to my Korean side came mostly in culinary form––I eat kimchi with just about everything to this day. My mother, however, set a culture of assimilation in our house, steering me and my sisters to speak English as well, or better, than those who might look at us as outsiders. Sometimes when I got out of line, though, mom would scold me, peppering her own sometimes broken English with Korean curse words that often had her fighting back a smile as she chastised me.

I never learned the language, and did not connect as a kid with what it meant to “be” Korean or Irish, but the ambivalence I felt in my formative years actually set me on a path to find a connection that runs far deeper than my Korean-Irish roots.

It’s true that when most people picture a rock musician in their heads, that image doesn’t look anything like me. But fortunately, I became the anomaly and found my identity––and my salvation––through music.

Music gave me my voice—not just the physical transmitter of the lyrics and melodies from the songs I write, but my place in this world, my sense of belonging somewhere and believing in something.

A Symbol of Two Heritages

None of this happened overnight and I was well into adulthood before I began to truly come to terms with who I am. And yet, I’ve never felt more at ease with all the complexities and contradictions inherent in the unlikely union between the parents who made me.

Many things along the way helped me get to this place––events small and

large that together pointed me toward an understanding, although rarely in the

moment.

When I was 13, I took my only trip to Korea, a month-long stay with relatives, and at that age I didn’t at all appreciate my exposure to the culture as much as I would have had I been older. Since my mother’s passing in 2012, my relationship with my sisters and my curiosity and connection with mom, who she was and where she came from, have deepened.

When I was in my late 20s, just after having returned from recording my debut album for A&M Records, my mother presented me with a black document bag and said, “Here, honey. Learn about your father.” Inside the bag were my father’s birth certificate, newspaper clippings about his career as a semi-pro baseball player and boxer, and–– most revelatory of all––photographs of half-siblings I didn’t know I had.

I met my half-brother and my niece for the first time just last year––I had never met a single relative from my father’s side before then.

In the absence of feeling deep familial connection earlier in my life, my songs served as the portal to explore my identity, often reflecting the duality as turmoil, my two halves in conflict. But finding my voice through songwriting was, in its own way, a journey toward self-acceptance.

I wanted my songs to have the power to persuade a short, stocky, shy

kid that he’s good enough, lovable as is, with his warped sense of humor and racial

makeup as random as a mix tape that segues Close to You by the Carpenters into Holiday in Cambodia by Dead Kennedys.

In the sunset years of her life, my mother, watching me struggle to discover myself, would often summon me to her den to share a quote from the philosophies of the Dalai Lama or Lao Tzu. As a parent of two children of my own, I can only now fully appreciate what must have been my mom’s frustration as the words of these great thinkers fell on my deaf ears.

As experiences and revelations built on each other over time, I finally began to

embrace my Korean-Irish identity and came up with what I consider the perfect way to visually articulate it. I visited a storied tattoo parlor in Philadelphia, where I asked my artist to tattoo on my upper arm a black-and-green yin-yang symbol, but with shamrocks where the small circles usually would be.

Two visual clichés of my Asian and Irish sides would come together into one unique representation. Three hours later, after thousands of needle pricks in my arm, I walked out of the shop with a tattoo that sums up who I am better than just about any of the more than 150 songs I’ve recorded.

The seemingly incongruous and contradictory forces within me were now joined

together, in Technicolor ebony and emerald.

Two heritages, two seemingly disparate worlds, a singular, circuitous journey––and now I was connected to all of it.

About John Kim Faye

John Kim Faye (www.johnfaye.com), author of The Yin and the Yang of It All: Rock ‘N’ Roll Memories from the Cusp, as Told By a Mixed-Up, Mixed-Race Kid, is a music“lifer” whose career spans four decades and counting. As a recording artist, producer, mentor, open mic host, and recently retired songwriting professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Faye has seen the music industry from every conceivable angle. His various musical iterations – the Caulfields, John Faye Power Trip, IKE, John & Brittany, and his solo works – have yielded over eight hours of recorded music, song placements in film and television, and substantial commercial and satellite radio airplay.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.