By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

Pasifika women across the United States are taking a stand against wage inequality.

Last month, the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF) based in D.C. and Empowering Pacific Islander Communities (EPIC) organization seated in southern California co-hosted a virtual panel in honor of NHPI Equal Pay Day. NAPAWF defines this day as when NHPI women’s pay “catches up” to what white, non-Hispanic men earned the previous year. The date this happened this year was Aug. 30.

The talk popped the can open on wage inequality disproportionately experienced by Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women, the ramifications to NHPI communities, and what people are doing about it. Approximately 50 registrants tuned in and another 35 viewed the livestream of the meeting, the first of its kind.

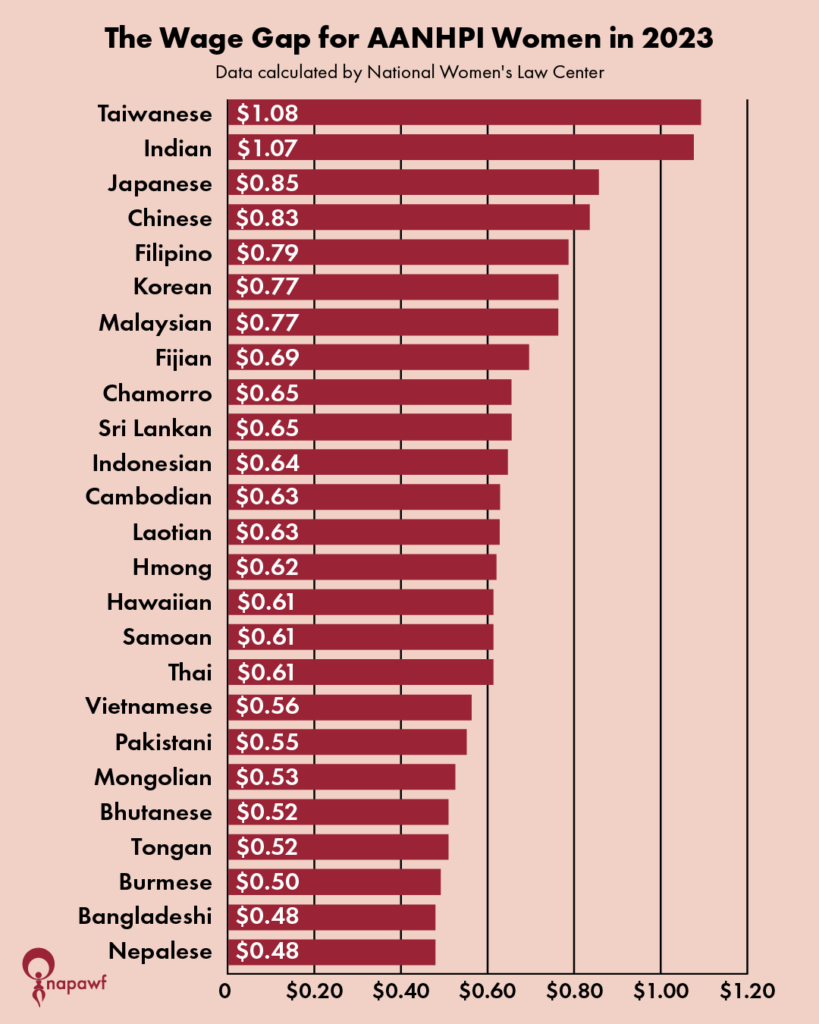

The nation’s latest wage data estimate that AANHPI women earn 80 cents for every dollar received by white, non-Hispanic males. The discrepancy is steeper for the NHPI part of the acronym. Women of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander heritage earn 61 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic males.

For some Pasifika women, surviving and succeeding under the systems that perpetuate this pay gap has entailed breaking free of them. They say that representation and communication are paramount to accessing the resources that provide the support, inspiration, and concrete assistance needed to advance in unfavorable conditions.

In the live streaming session, Estella Owoimaha-Church, EPIC’s executive director, Shadelle Ku’uipo Hooper, Founder of Aloha Youth Organization of Oregon, and Fuatino Ruta Lauleva Lua’iufi Aiono, founder & director of M.A.N.A. Pasefika shared how economic statistics look for actual people in NHPI communities.

“It’s not about just cents to the dollar, it’s about our real, lived experience,” Owoimaha-Church said, as she opened up the floor.

She stated that the wage gap among Pasifika women is only the beginning of a conversation about greater systemic injustices and inequities that require amplified NHPI narratives to be tackled in a real way.

Owoimaha-Church was born and raised in Tongva Lands, currently known as Los Angeles, by a mother from Independent Samoa who had been raised in South Los Angeles. Her father was an immigrant to the U.S. from Nigeria.

Owoimaha-Church’s mother came to the U.S. believing she would one day earn enough to take care of her family, village, and homeland. This American dream turned out to be evasive.

When Owoimaha-Church was a young adult, she was responsible for her youngest siblings, taking them with her to class in order to attain her higher education. College liberated her from the strict, traditional West African household in which she grew up while saddling her with student loans she continues to pay off today while serving as the primary caretaker for her elderly parents, being a mother, and running an organization.

An educator for nearly two decades before transitioning to her role at EPIC, she said she really noticed American society’s low valuation of workers of color as a teacher during the pandemic.

“Our bodies are beyond expendable, or at least that’s what folks think. Our bodies as Indigenous peoples, as PI folks, as people of color. We are seen as exposable, or disposable,” she said, alluding to the physical and emotional toll of the kind of work that NHPI women and other people of color do. She lost three colleagues – all Black men – not to COVID-19 but to stress and community violence.

Shadelle Ku’uipo Hooper spoke further to the toll of low-paying labor disproportionately borne by Indigenous and NHPI workers, and the vicious cycle that this causes.

Born and raised in Moloka’i with Black and Native Hawaiian heritage, Hooper went straight for housekeeping jobs once she moved to the mainland without a college degree.

“At the time that seemed like the route, the job for someone like me, like Black Pacific Islander and a female. And so, I knew for sure, oh yeah, I’d be hired, that’s like the go-to job,” she recalled thinking.

In the middle of the pandemic, her childcare duties as a single mother of four children forced her to choose between high-intensity, low-pay housekeeping and care of her family. She chose her family. The price of this was ending up on government assistance after depleting her savings.

“It’s like this trickle effect of like, you’re not trying to get to that point, but because of our status as Pacific women, it’s kind of the last resort, or like our only option,” she said, loathe to become reduced to the welfare family stereotypes.

“I honestly don’t think any of us want to end up like that. We just have this gap that we’re trying to get out of,” she said.

Shedding what she described as a Pacific Islander tendency to keep going no matter how bad things get, she stopped to ask herself how she could avoid working all day for someone else with only the leftovers for her family.

The old Hooper had gone back to work a week after giving birth. She had to hurry up and get money to take care of her family. She did not know that, by Oregon law, she could have received three months of paid leave and an additional three months if needed. “A lot of people that look like us don’t know that at all,” she said.

The new Hooper decided, “Yeah, we’re not working ‘til we die and have nothing to show for it. We’re tired of working; we’re tired of being in like this survivor mode of having to choose between our families and work. We can do two – I’ve seen people that don’t look like us do both, so why should we have to decide that?”

She entered the human resources department of a construction company, which is when she learned about the right to maternity benefits she had not known as a domestic laborer.

Becoming a benefits coordinator with no prior formal training emboldened her to try something else during the pandemic. She became a contractor for everything she was good at.

She began taking event photographs for Black and Pacific Islander events. She plugged into the Black Pasifika community and started earning money braiding hair. And this March, she founded a youth organization and recreational center in an unincorporated community called Aloha, Oregon, situated between Hillsboro and Beaverton. A large reason for starting the venture was to do work that would also allow her to watch over her children.

Reaching financial stability on one’s own terms, challenging as it is to achieve, has been a sweeter victory when drawing from cultural knowledge and community connections.

“We are Indigenous scientists and bridge builders and wayfinders,” Owoimaha-Church reminded everyone on and off the screen.

“We’re natural pioneers, we’re innovators, and that’s something during adversities. We always show up, we always create, and we always do something to make change,” Hooper agreed in her segment.

Often, what blocks women from leveraging this strength is being geographically distanced from the collective caretaking systems of their cultures and scattered throughout the American diaspora as the country’s most uncompensated caretakers – mothers.

Living far from her Pacific roots, Owoimaha-Church had less-than-ideal experiences becoming and being a mother. After a highly traumatizing birthing process, she contended with protracted postpartum depression. Looking back, she wished someone had told her that the postpartum period can last longer than three months of maternity leave – that recovery takes as long as one needs it to take.

“I actually didn’t hear those words from someone until very recently, when I was able to get a therapist who looked like me,” she said.

Hooper said, “representation matters,” and that this is why it is important for Pacific Islanders to speak up for themselves. She said that she learned quickly that her island accent is something to turn off if she wants to be taken seriously in rooms full of erudite people and low diversity.

“Somehow my accent gives off the vibe that whatever I say doesn’t matter,” she said, cautioning the panel audience to make sure to use their voices anyway.

Without the women and resources around her, Hooper said would not have been able to find her way out of the predicament she was in just a couple of years ago.

She shouted out to the KALO Hawaiian civic club in Beaverton that gave out food boxes and administered vaccines during the worst of times.

“That kind of work is how we close the gap, this kind of work, these panel discussions. Voices are being heard, and people are just bringing awareness to, hey, there’s still a gap, here. Generations have gone by and we’re still struggling,” she said.

Hooper said that many Pacific Islanders do not even know about the services that exist, leading right back to the paramount importance of representation.

She mentioned how hard it is just to find a workout video on YouTube. “It’s all full with white content,” she said, to the extent that she has to type “Pacific Islander trainer” or “Black trainer” into the search bar in order to locate videos created by diverse health professionals.

Resources for mothers

Fuatino Ruta Lauleva Lua’iufi Aiono, the third person on the panel, provides birth resources and services from Pacific Islander women for Pacific Island Women and wants to get the word out.

She greeted the gathering in the Samoan language and shared that she had grown up splitting time between Fasito’o Uta and Malie villages on Upolu Island in Western Samoa and the mainland. She now divides her presence between there and San Francisco.

In 2013, she became a traditional birth attendant and later became founder and director of M.A.N.A. Pasefika, a network of Micronesian, Melanesian, and Polynesian birth workers providing culturally grounded programs to Micronesian, Melanesian, and Polynesian parents before, during, and after giving birth. The concurrent mission of this work is to help Pacific Islanders maintain autonomy and ancestral knowledge from the Pacific Islands and apply these values and their benefits directly to the next generations being born.

M.A.N.A. Pasefika, holds Tama’ita’i Toa (“heroine”) healing space for mothers once a month and will soon launch a childbirth education series for expecting families, as well as Pacific Islander doula and birth navigator circles.

The network is inviting inquiries from ethnic Micronesians, Melanesians and Polynesians (including Native Hawaiians) interested in this programming, which includes guidance on specific aspects of childbirth and childrearing like labor positions, breastfeeding preparation, and pregnancy nutrition.

There is no geographical restriction to participation – the only requirement for registrants is that they be of Pacific Islander heritage.

She said that white women take up a lot of space in the birth industry.

“Having a natural birth, having a nice post partum…doesn’t feel like something that, in my experience, is something that seems like is for us,” she said.

“A lot of us are community-oriented so sometimes it takes like, ‘my cousin did this,’” she added.

Aiono expressed awareness that it is hard for low-earning NHPI people to invest time and money into learning about Pacific cultural practices and attending births, which occur around the clock. She said that she had had the support to be able to figure out what she wanted to do with her life after college.

“I think if I hadn’t had that space, it would have taken me a lot longer to find my way into holistic health, natural health, herbal medicine, natural birthing, all these kinds of things because I would have been in that survival mode that a lot of our families are in,” she said.

She echoed Hooper’s observation that Pacific Islanders still exist today within structures founded in colonialism forcing them to “literally work until we die.” For some, doing so sometimes even becomes a point of pride for some people in the community.

However, Aiono said she has noticed a huge shift in consciousness among Pacific Islanders understanding their positioning as Indigenous people in the U.S., and that there is a heightened demand to see and serve the “invisible ‘PI’ in ‘AAPI.’”

Owoimaha-Church presented a major question about how to respond to this demand.

“How do we get back to all the things that are us; how do we get back to all the things our ancestral knowledge has already gifted us with?” she asked, stating that fewer and fewer people remain on island to be an active source to inform collective community caretaking and cultural knowledge in the U.S.

Pacific Islanders, Aiono noted, sometimes have to live together in the States to be able to afford housing but still have less access to multigenerational living than in the islands.

“That’s how we live when we’re in our homelands, right? Everyone’s together – if we’re not under the same roof, we’re like under the same little circle of roofs,” she said. She reminisced about growing up with layers of extended family in Samoa and helping her “grammy” at the family store.

In addition to feeling a sense of community, she learned the tradition of responsibility from her grandmother, who taught her: you know a Samoan from the way they talk and walk and sit.

“I loved that way of living,” she said, despite the presence of one particularly “scary auntie.” She said that she longed for this sense of community when living with just her father and brother in an isolated area of upstate New York after moving to the States as a young girl.

She said that the work she hoped to achieve with M.A.N.A. is to reinforce multigenerational community structures in the Pacific Islander diaspora.

“How can the elders be empowered to share their knowledge when we’re living in diaspora, and be encouraged to bring things from the islands, and really share them and see that those things have value and worth, and that, frankly, white people will pay thousands of dollars to hear about in a workshop,” she said, sharing the puzzle that motivates her.

The panel was indeed just a beginning – EPIC is one of eight partners with NAPAWF in the new AAPI Gender Justice Collaborative gender justice movement seeking to bring voices of AANHPI people and organizations with shared values into policy making.

Public policy challenges

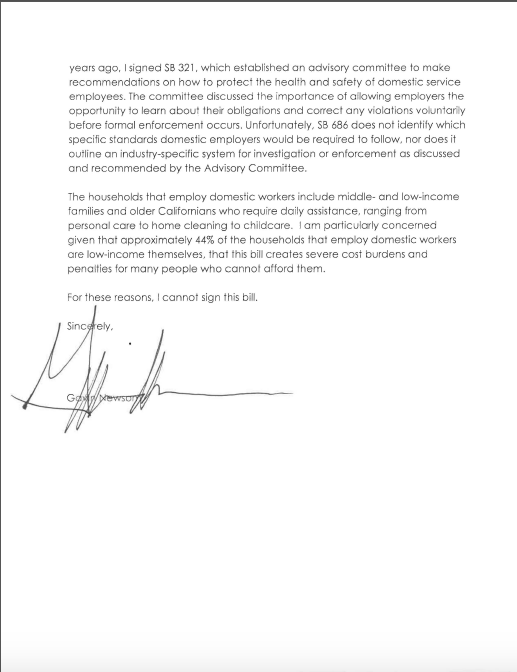

As a coda, just one example of a policy development in the country that could continue challenging NHPI women and others in low-paying, high-intensity jobs is the recent denial of Senate Bill No. 686 in California. Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the measure on Sept. 30, just days after the NHPI Equal Pay Panel.

If passed, the legislation would have held private household employers of domestic service employers such as nannies and housekeepers accountable to the state’s occupational safety and health laws.

Governor Gavin Newsom’s message explaining his decision stated that “private households and families cannot be regulated in the exact same manner as traditional businesses.”

The letter suggested that some of the upgrades required by the bill (e.g. the installation of emergency eyewash stations in homes for any worker handling household cleaning chemicals) were unreasonable to expect domestic employers to make by the Jan. 1, 2025 deadline proposed by the bill.

The governor issued a reminder of measures he had already taken to better protect the safety and health of domestic service employees and concluded by stating that 44% of households employing domestic service employees are “low-income themselves.” He said he worried that enforcing up to a $15,000 fine per violation of workplace laws upon this demographic could place more expenses upon those who are already poor.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. A big thank you to all our readers who supported our year-end giving campaign. You helped us not only reach our goal, you busted through it. Donations to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews are tax-deductible. It’s never too late to give.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.