By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

Phanat Xiong (“pa-na zhong”), 35, still has nightmares about the house in Oroville, California, that he and his family moved into right before he entered high school.

That’s when and where his troubles began, long after he had stopped believing in the spookier of the Hmong stories that his mother used to tell him at bedtime.

One night, he made his way upstairs with his older brother not far behind him. The building, built in the early 1900s and towering over the others on the block, creaked underfoot as the boys ascended to the second floor and proceeded down the hallway.

Xiong entered the room first, got under the covers, and shut his eyes. He heard his brother arrive, close the door, turn off the lights, and get into his own bed a few feet away. But something was wrong. His brother, usually talkative at night, was completely silent.

Just as Xiong decided to see what was going on, he heard a rustling noise, as if his brother had cast his blanket off and risen. When Xiong opened his eyes, there was indeed a blanket on the floor. But no one else was in the dark room, and the door was still closed.

A beat later, his brother opened the door and flipped on the lights. Seeing the look on his younger sibling’s face, he turned right around and ran out with Xiong on his heels.

The Internet is full of singular yet not dissimilar stories like this one, amplifying a phenomenon of widespread scary storytelling across the Hmong community that is in no way confined to Halloween.

A Facebook page plainly titled Hmong Ghost Stories has 43,000 followers. Though not all of the followers are necessarily of Hmong ethnicity, the following amounts to 13% of the total Hmong population in America.

Sites like this have inspired retrospection, like clips from throwback Hmong horror films of zombies in ethnic dress climbing out of dirt fields and graves.

Txiv Nus Tooj Thus Thiab Muan Kkauj Sees, Vang’s International Video Production

On YouTube, Leng Vang, an intensive Care Unit nurse in Merced, California, doubles as a Hmong scary story content creator. His videos, narrated exclusively in the Hmong language, center around myriad themes, like haunted places, natural features, spiritual or religious figures, historical events and, of course, things healthcare professionals have witnessed.

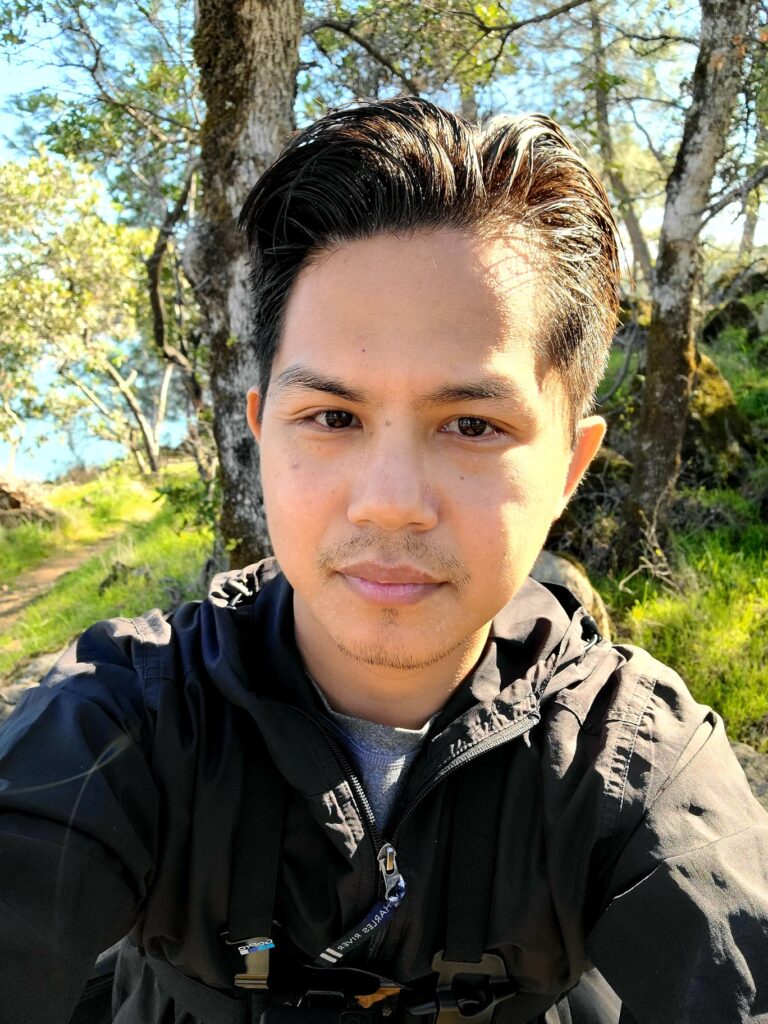

Last year, Xiong became a contributor of scary Hmong content when he launched a website called HmongTales last October.

He put his college degree in graphics, multimedia, and web design to use to create a submissions-based site for news and events important to the local Hmong community. Readers started submitting horror tales along with news, and soon, statistics revealed that site visitors were roughly 90% more interested in scary stories than in anything else.

To understand Hmong obsession with the horror genre, one must backtrack along the Hmong American experience; a tangled intersection of roots in ancient oral traditions, spiritual beliefs, wartime trauma, displacement, refugeeism, immigration and the power of storytelling help cope with the past and perpetuate cultural identity across generations.

Xiong, whose family belongs to the Hmong clan of the same name, was born in Phanat Nikhom, the largest holding center in Thailand for refugees of the Vietnam War and the Secret War in Laos, followed by the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia who were cleared for resettlement in the U.S. or Europe.

Xiong’s parents were from Laos, fleeing the vengeful wake of U.S. withdrawal from the region after thousands of Hmong people had fought on America’s behalf in the “Secret War” against the Communist Pathet Lao.

With nine boys to raise, Xiong’s parents told several cautionary tales that were all-out ghost stories. One favorite was a warning never to speak loudly at night or utter one another’s names. Otherwise, a dab (“da”), a spirit, would come to get them, impersonating a sibling to get close.

“I mean we were terrified, you know? It definitely kept us quiet at nighttime,” Xiong told AsAmNews over the phone on a Sunday afternoon, while on break from his shift on the transportation team at a rehabilitation center. He laughed, talking about how he used to deal with the jitters.

“I would go to sleep and make sure I slept kind of close to my brother because I’m scared. And I’m sure I’m sure they were scared too. So there was like three of us sleeping on one bed. You either wanted to sleep by the corner or you’ll sleep in the middle, but you don’t want to be the guy sleeping on the edge of the bed,” he said.

Eventually, his childhood fears calmed until that one night in the creepy house. After that, the strange visions and incidents continued and intensified. Xiong, who believes in science, kept thinking of explanations for why these things could be happening to him. Maybe he was tired. Maybe his mind was just playing tricks on him. At the same time, he was truly afraid.

“So I used to talk to my dad about it. And he was just like, ‘You know, it is real. You just have to face it, and then maybe one day, it will go away.’”

Sure enough, the paranormal activities stopped, allowing Xiong to once again reconcile with his firm belief in science … for the time being.

Spiritual traditions and shamans

For some Hmong people tormented by paranormal experiences, it can be because they are being called to ua neeb (“ua neng”), the practice of 5,000-year-old shamanistic traditions.

This was the case for Billy Lor, 25, who has been a txiv neeb (“tse neng”), a master-father of spirits, for over a decade.

He didn’t grow up in the tradition.

Lor’s parents, both now deceased, were also Hmong refugees out of Laos. They met at the refugee camps and were arranged into marriage because of a favorable relationship between their families. Lor’s mother had ties in the U.S., but his father had nobody. So once in America, he began bringing the family around to churches to try and restore a sense of community after their multiple displacements.

Consequently, Lor’s upbringing in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, was completely cut off from Hmong spiritual traditions or knowledge. But during his preadolescence, things started getting weird on their own. Instead of having strange visions or experiences like Xiong had had, Lor started having bouts of physical sickness and pain.

By this time, Lor’s parents were divorced. Freeing herself of the Christian framework, his mother began contacting local Hmong shamans through her side of the family in 2009, when Lor was 11.

Four years later, when Lor was starting high school, he began undergoing tests to see if his ailments meant that he was supposed to be a shaman.

For the test to work, he had to cross paths with a shaman who had the right qhua neeb (“koa neng”), or “spirit guides,” for lack of a better translation. These are the spirits that are attached to and assist each shaman.

“There’s shamanism, but it breaks out into tons of different branches, tons of different lineages,” Lor said. “So you need to find a master who has the same spiritual lineage as you and this is hard because there’s no ghosts whispering in my ear telling me what lineage they are. So you’re just guessing and guessing and guessing until you find the right one.”

When Lor found his xib fwb (“see-fu”), or compatible spiritual teacher, he walked into a regular suburban home and took a seat on a bench that signifies a flying horse by which a shaman rides through other worlds.

The attendants at the test put a red cloth mask over Lor’s face, fit donut-sized tswb neeb (“churh neeb”) brass bells over his index fingers, lit incense at an altar set up against a wall, and hit a gong.

“They hit that gong and right away, in an instant, you can’t feel your body. Like, you literally cannot,” Lor recalled. He likened what happened next to being on a high that was not entirely pleasurable, either. He was completely conscious as he madly jumped on and off of the bench, gasping for air. Yet, he had no control over his body.

“So in my mind, I’m dropping F-bombs left and right, because I’m terrified. I’m confused,” he said.

Three adult men had to hold him down to force blessed water down his throat. Then, boom, he was back.

As a shaman, Lor helps people in his community bless homes, open businesses, lay the dearly departed to rest, honor ancestors and welcome babies. He also provides holistic healing for those whose physical ailments or emotional problems are because one of the 12 souls inhabiting each human individual is out of alignment.

Going by the content creator name Hey Billy, Lor appears at events like the recent “2nd Annual Story Night of Terror” at the Hmong American Center and teaches courses about Hmong shamanistic beliefs and practices.

One of these practices is hu plig (“hu plee”), or soul-calling, for lack of a better term. This takes place during the Hmong New Year. To be celebrated between early November and Dec. 31 in different parts of the U.S. this year, this occasion is the busiest for txiv neeb.

During hu plig, rituals, chants, and offerings of food serve to call all ancestor spirits back to their proper realms. All souls of the living come back home to their proper humans to make everyone whole and start off the upcoming year on a positive, balanced note.

Scary moments abound in the calling of a shaman. In his interview with AsAmNews, Lor told a story about one txiv neeb who was flown all the way out to Paris by a man and his new wife to bless their house. Unfortunately, he forgot to start with protective chants once he got there. The furious ghost of his client’s deceased spouse stalked the shaman while he was in France and even followed him back to the U.S. – a fright too much to bear. The shaman left the practice.

Lor also shared a time when he was helping a family honor its ancestors and had to exorcise an eight-foot-tall monster that surprised him at the opening of a stairwell and kept nearing him while he performed a routine healing ceremony for the matriarch of a family.

“At one point it seemed like the room was so dark that the only things I could see was the light at the window and the candles on my altar. But everywhere else, you know, I would look like five feet backwards and it’s just darkness and when I would take off my veil it’d be just a normal room. So I knew the spirit was was pressing me down with energy and shifted the ceremony from a healing to a full blown exorcizing the spirit out of the home,” Lor said. His students that day helped by physically surrounding him while doing their own chants.

Lor could fill a book with these stories, and he intends to. Like non-shamans his age, though, he also knows about Hmong urban legends far removed from the traditions he practices. He said that everyone has heard the one about a cute ghost girl who hitchhikes along a California freeway, only appearing dead once her hapless ride-givers peek at her through the rearview mirror. After dying on the road years prior, she is still trying to get home to her worried mother.

Xiong has taken to curating more of these modern “hearsay” submissions from the Hmong American diaspora for HmongTales now that he has confirmed how popular they are. He also knows of old-world classics unrelated to shamanism but baked into Hmong folklore and mythology that precede the everyday scary stories of today.

His grandparents back in Laos taught him about Phim Nyuj Vais, a powerful being that Xiong describes at the top of the spirit food chain. With a gorilla’s body, a wolf’s head, and a red spot on the chest, the shapeshifter can also pose as an elder seeking tobacco to decide whether someone is good or bad, like a metaphysical trick-or-treater.

The spirit can also impersonate others, luring people into their domains in the jungly mountains. A person might also see Phim Nyuj Vais in monkey form, munching on something. They won’t know until it’s too late that this means the spirit is eating their insides, feeding off flesh and blood to fuel its immortality.

“Some say strong gusts of wind announce their presence along with their cries that can make you bleed from ears or eyes,” added author and illustrator Tou Her in Great Lake, Minn., who chatted to AsAmNews by text.

Hmong people are known to burn chili peppers or stick knives deep into fires before waving them around to ward off such beings. They also avoid cooking animal intestines so as not to attract hungry spirits.

In the U.S., Her’s friends have left food out to appease Phim Nyuh Vais while camping. They were always too scared to verify whether the source of the noises outside in the middle of the night were wild animals or spirits.

Her has also heard of Phim Kong Koi, the one-legged rival brother of Phi Nyuj Vais. The jungle ghost takes on the form of a bird, a bat, or sometimes a bobcat that cries,” Kong koi, kong koi!”

Her’s brother scared him with stories of Phim Kong Koi when they were younger.

“He would say that if we didn’t tuck the blanket under our feet at night, a monster would lift our blanket and suck our blood through our feet. The monster would make a thumping sound because it only had one leg and would have to hop around. I believed my brother’s story and tucked the blanket until I was 12,” he admitted.

Both Her and Xiong said that Hmong Americans do not really claim to have direct encounters with these beings. Xiong said, however, that Hmong American hunters invoke Phim Nyuj Vais to effectively keep competitors off their turf.

These myths and spiritual philosophies that coexist alongside them are part of an animistic belief system that runs so deep that the question of whether it is “real” can become moot.

The most salient example of myth blending with reality is dab tsog (“da chaw”), a demon that attacks by night, sitting on people’s chests and sometimes attempting to strangle them. That’s the PG version – Xiong says that a Hmong belief is that these spirits also copulate with their sleeping victims, causing infertility in men and women over time.

From the late 1970s through the early 1980s, 117 Hmong refugees in resettlement communities around the U.S. died in their sleep, often after a period of resisting sleep to avoid nightmares and flashbacks. A peak 92 deaths all occurred between 1981 and 1982.

Only one of the deaths was that of a woman. Everyone else was a physically healthy male. The men’s median age was 33, and they had only spent a little over a year and a half U.S.

Medical authorities first dubbed the mysterious circumstances as Asian Death Syndrome before researchers came up with Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS), still without scientific explanation. Hmong elders said that dab tsog got them before anyone could help.

Retrospective analyses wager that the wave of sleep deaths was caused by a combination of war and refugee trauma, severance from spiritual support networks, shame among male providers at not being able to provide for or protect their families, and, yes, dab tsog. Or at least the belief in it.

Scientists have replaced arcane monikers like “voodoo death” with “nocebo effect” – the power of belief to kill with terror.

The deaths catalyzed a project of late horror filmmaker Wes Craven, who directed the popular Scream franchise. Less known as the bird lover and philosopher he also was, Craven’s first film in 1972, The Last House On The Left, was an allegory for his opposition to the Vietnam War.

As a boy, Craven had had his own bad dreams while growing up in Ohio with an alcoholic father in a repressed fundamentalist Baptist home. This personal history plus the plight of the Hmong people prompted him to make Nightmare On Elm Street in 1984. The film launched a blockbuster franchise of terror reigned by Freddie Krueger, who, with his melted features, holey striped sweater, lewd threats, and blades for hands, hunted down and killed kids in their dreams.

Some speculations about the Hmong night deaths have cited a lack of spiritual, emotional, and communal outlet for the refugees after they were thrown into Western society. This leads to the substantive part of even the silliest Hmong scary stories – they are but part of the critical role of storytelling overall in the Hmong civilization, which did not have a written language until the 19th century.

Even the txiv qeej (“tse kheng”), lead player of the qeej (a bamboo reed mouth organ) at ceremonies, is considered to be a storyteller and spirit-caller because the instrument is an extension of language. Each note is a word.

At funerals, the txiv qeej plays to awaken the soul within the dead and send them on their proper paths. According to artist Her, one soul stays with the body and becomes an ancestral spirit. Another goes into rebirth, ideally into the same family. A third goes to the spirit world and wanders ever after.

The Secret War

Her, born in the refugee camp of Ban Vinai in Thailand and who immigrated to the U.S. in 1985, talked about what the Secret War and its aftereffects did to the Hmong people and their traditions.

“The stories about the secret war haven’t really been taught at all, he said. But, we do hear tidbits about it. The US pulling out made it hard for those left behind and fleeing to Laos was the only recourse,” he said.

Her grew up in central Wisconsin, “sort of stuck between two worlds as a first gen.”

He said, “It was a tough transition period where the Hmong had to learn how to live by the rules of Western society.”

Growing up, he heard many stories about curses and hauntings in the Hmong community that happened because of malevolent spirits generated by unfulfilled or broken promises.

“Hmong people in general hold onto grudges for a long time,” he said. “So it carries into the afterlife in the form of hauntings and bad luck.”

Her’s illustrated book, Perilous Journey, is a wrenching documentation of this exodus, based on real accounts of parents accidentally overdosing their children with opium in their attempts to keep them quiet at night while being chased by the Pathet Lao, or losing infants to the rushing waters of the Mekong River in a crossing.

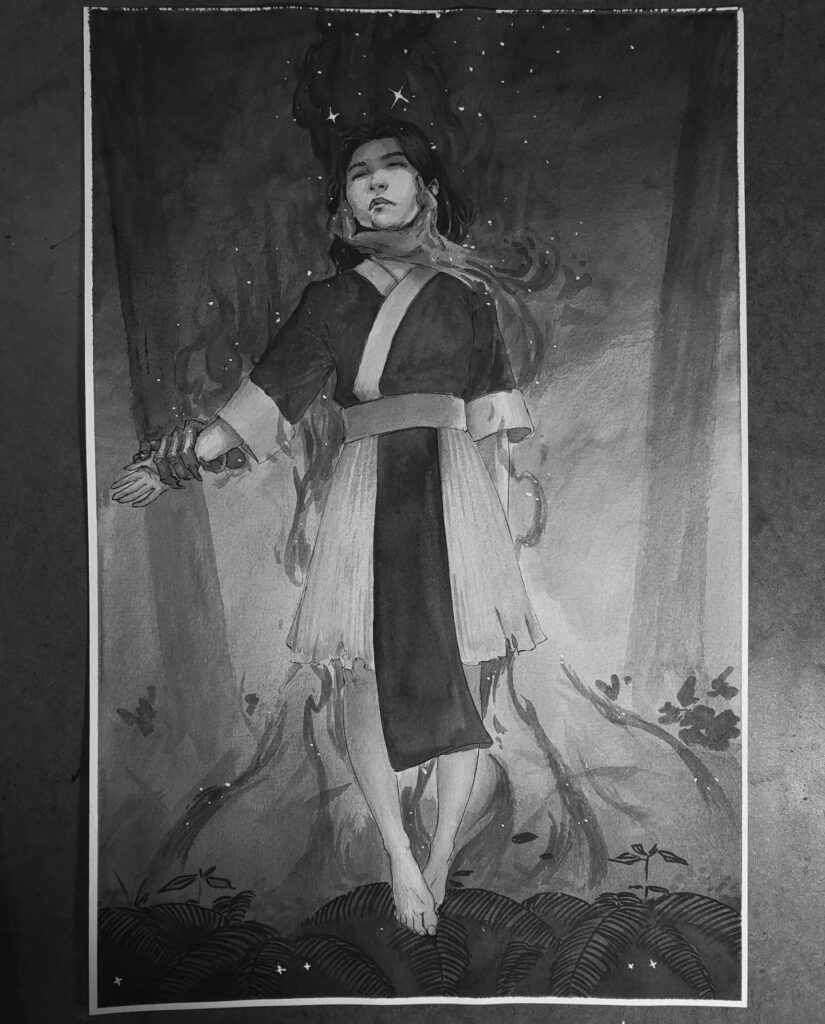

One of his drawings in the book depicts the death energy that flowed along the path when the Hmong were fleeing Laos. Sharing the image in an Instagram post last year during an “Inktober” campaign to make a drawing for every day of October, he wrote:

Along the trails, the emanation of death permeated the earth. All the emotions that accompanied the dying drew in all sorts of spirits. Some deaths even birthed new spirits to haunt the living. Each night the spirits chased after their loved ones, not wanting to be left behind.

Directly or indirectly, scary storytelling may continue helping Hmong Americans process experiences, fears, and beliefs within an accepting community. Scary stories that survived a harrowing shared history can also carry forward traditions and a sense of identity even an ocean and generations away removed from pre-war Hmong society.

Tshajlij Xiong (“jja-lee zhong”), no relation to Phanat Xiong, grew up in Fresno, Calif. but moved to Minnesota over a decade ago to be around a higher concentration of Hmong people. In an effort to preserve the intangibles of what it means to be Hmong, he formed Tshajlij Productions with no film experience but a group of creative friends who shared his mission.

Whether injecting elements of comedy or romance into serious stories, the company strives to take different twists on old narratives to help people in the present relate to and remember some of the oldest and most fascinating Hmong stories.

Their 2022 short film, Wb Lub Tsev (“ou luchay”) – Our Home, is based on an old Hmong belief that people blocked from being with the person they love can commit suicide and come back as spirits luring the object of their lover into the underworld. When this happens, shamans need to bring back the souls of the surviving lovers before they die in the mortal world while following their ghost partner into eternity.

In the movie, a young couple goes on a journey populated with frights such as poj ntxoog (“bbun zong”), child demons and dab tuag (“da tua”), the undead. A surprising ending brings out the romance and poignancy behind something normally thought of as purely terrifying.

As for Phanat Xiong, he began to really research all things supernatural a few years ago. He took on the study with even more vigor a couple of months ago after he started having strange experiences again, like seeing a heavy mug of tea sliding across a café table or finding a dark portal the size and shape of an American football open in his hallway during the daytime.

What he wants everyone to know is that other cultures have their own dab tsog, spirits, ghosts, monsters, and unexplainable things. They just might not talk about it as freely as he now does.

Xiong has stopped disbelieving himself.

“In the Hmong community, there’s going to be believers, and there’s going to be people who don’t believe. For me, I’m not trying to convince anybody to believe me. I just want to tell a story,” he said. Having gone through a solid period of life when he did not believe any of these ghostly stories, he understands if people do not believe him. And that’s all right.

Despite the fact that he is sliding toward becoming a believer again, he thinks that he will spare his daughter from the scary stories he grew up with. Today, Halloween, is only her first birthday.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.