By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

Nyob zoo xyoo tshiab (“nyaw zhawm hyown cha”) – welcome the new year!

On the precipice of 2024, Hmong alums who attended College de Samthong, Lycée de Vientiane, Dongdok, and other education institutions in Laos from 1960-1975 gathered in an annex of the Fresno County Fairgrounds in Central California.

Sporting bell bottoms and shoes with a lift as a throwback to their student days, they came from across the U.S., as well as from Laos, Thailand, France, China, and Australia to be together. Some of them had not seen one another for nearly 49 years.

The reunion was a poignant finale to Fresno’s Hmong Cultural New Year Celebration from Dec. 28-31. For all those who attended the four-day affair, it was a time of looking back while moving forward, of trying to remain authentic to Hmong culture while popularizing it.

Every year, Fresno celebrates the Hmong tradition of honoring ancestors and rejoicing in a completed harvest in the late fall and early winter. Other Hmong communities across the U.S. host events as early as September to optimize their cities’ scheduling and avoid conflicting with one another.

Dr. Toulu Thao, leader of The Hmong, Inc. the nonprofit that won the contract to run the 2023 edition of the Fresno Hmong New Year, was part of the big student reunion, too.

He left the mountains of Xieng Khouang province in Laos when he was about 11 years old to attend school in the capital of Vientiane.

Prior to World War II, Hmong children had elementary instruction before moving on to the school of life, where they learned from the oral traditions and practices of the community. Thao’s mother had been one of the first Hmong children to access formal schooling after she descended from the highlands to attend a French institution in the center of the Lao kingdom.

Years later, Thao was one of a few hundred Hmong children after her to make the long journey to the schoolroom.

As a male, the alternative would have been to pick up a rifle and fight in the Laotian Civil War between the royal Lao government and the communist Pathet Lao from 1959-1975.

When the U.S. became involved in Laos circa 1964 by way of the Vietnam War, the CIA began recruiting ethnic Hmong men and boys from their peaceful, agrarian societies to its ”Secret War” to destroy the Pathet Lao and its supply lines to Vietnam. Preadolescents were not off limits for drafting.

“I remember those days. If you walk in the street and you don’t carry your student ID, you disappear and you go into the army,” Thao said, in a phone call with AsAmNews.

In order to attend school so far from home, he entered a dormitory where there were no parents around. “We were just kids, basically, trying to care for another,” he remembered.

1975 was the last class of Hmong graduates in Laos for a long time.

This was the year that King Savang Vatthana of Laos abdicated his throne. The Pathet Lao took over and established the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos. The U.S. abruptly left the region after the end of the Vietnam War.

The vengeance that the Pathet Lao exacted upon the Hmong people for fighting on behalf of America turned the Hmong people into refugees who went to camps in Thailand before migrating to the U.S. and other far-flung destinations around the globe.

Reuniting Hmong alums in Fresno found that many of their former classmates had already passed away. But the remaining people were glad to see one another alive and well, having survived a lot more than the march of time.

“It was so beautiful to see each other after all these years. We smiled – we still lived,” said Thao.

Thao came to the U.S. in 1982 at age 16 and went on to earn advanced degrees and become a pioneer and activist of the Hmong American community. He was a long-time federal employee at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development before his recent retirement.

He said that the experience of adapting to life in Vientiane in the 1960s and 1970s as boys was what gave him, his peers, and the earlier first Hmong refugees the strength to migrate to the U.S. and establish the Hmong American community.

Before the festivities, he told Fresnoland that he took on the New Year festivities in Fresno to give back to the community.

The state’s farm-rich Central Valley, from Chico down to Fresno, is the seat of many Hmong communities. According to the Pew Research Center, 35,000 Hmong people reside in Fresno – the largest Hmong population in America second to St. Paul, Minnesota, which celebrates the Hmong New Year on the weekend after Thanksgiving.

Hmong New Year is a time to rest and revel after endless hard work. Fresno’s celebration also helps perpetuate tradition and make sure culture and stories do not fade away in the Hmong diaspora. The event has become a way for the Hmong community to check in with itself as it evolves.

Fresno’s celebration at the end of each calendar year is the largest Hmong cultural event in the country, drawing hundreds of thousands of people, mostly of Hmong, Lao, and Thai heritage, from around the country and the world.

The City of Fresno has stated that pre-pandemic week-long celebrations used to bring in well over 120,000 visitors. The first post-pandemic event in 2022, cut back to four days, was attended by approximately 44,000 people.

The 21st District Agricultural Association (DAA), better known as The Big Fresno Fair and administrator of the celebration venue, did not respond to AsAmNews’s inquiry for details about attendance, vendor participation, and revenue in 2023-2024.

But tens of thousands of people certainly showed up despite hard, unpredictable rain showers that periodically pelted the normally drought-tormented San Joaquin Valley region on day three.

For more than three decades, various community groups such as the Hmong Cultural New Year Celebration, Inc., the Hmong International New Year Foundation, and the United Hmong Council have shared responsibilities in coordinating festivities.

In some years, the process of running the largest gathering of the Hmong community and celebration of Hmong culture in the U.S. has been hotly contested between organizations.

Having won the sole rights to manage this year’s festival, The Hmong Inc. undertook its first large event since its formation a few years ago.

Fresnoland reported that the nonprofit expended over $439.020 in hopes of upholding the standards of the past years’ events while taking programming to another level.

One historical highlight was attendance by Sisavath Inphachanh, the Ambassador of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic to the United States. Thao invited the Ambassador at the behest of both Hmong and Lao community groups.

Fresno Center CEO and president Pao Yang told Fox 26 News that this was the first time a Laotian ambassador attended the event.

Inphachanh’s presence symbolized progress from decades of tension between Hmong and Lao people in the wake of the U.S.’s Secret War in Laos, during which it dropped 2.5 million tons of cluster bombs across the land, particularly in the mountainous area where most Hmong people lived.

The warfare killed 200,000 Lao civilians and soldiers – a tenth of the population at the time. The Hmong American Center estimates that the conflict also killed approximately 35,000 Hmong – a tenth of the ethnic population.

The Legacies of War project that spreads awareness of the historical events that have continuing ramifications in the present, counts that unexploded ordinances (UXOs) have killed another 25,000 since the “secret war.” UXOs continue to maim and kill people every day in what remains the most bombed place on Earth.

“It’s been fifty years. We died, they died, and I think it’s time to heal,” Thao reflected later, noting how humble Inphachanh had been for such a high-ranking official.

“History is history – it cannot change history, but we can move forward,” Inphachanh told the crowd, as quoted in many local news sources after the opening day of the Hmong New Year celebration.

Opening day featured a ribbon cutting at the entrance arch and parade of community and cultural groups with remarks by various leaders. Mayor Jerry Dyer, who has attended the event for the past 30 years, was there. So were assemblymen from throughout the Central Valley, along with a representative from California Governor Gavin Newsom’s office.

In the following days, people continued arriving in droves, gracefully stepping over any puddles that only served to reflect their radiant ethnic clothing and jewelry more. Tiny bits of silver, beads, and charms twinkled and jingled like tiny crystalline bells as friends and family walked around in groups.

The path to the fairgrounds entrance was flanked by beauty and health product vendors, and large tents sponsored by a church offering free Korean lessons for the growing number of Korean cultural fans who want to learn the language.

The pastor of the church had approached Thao leading up to the event and loved the spot he was given.

Not much farther inside, lines of Hmong men and women faced each other, tossing balls back and forth in a traditional courtship ritual. They seemed to symbolize the true gateway into the festival.

The air in the huge, open fairgrounds was fragrant with rain mist and food smoke, living up to the holiday’s alternate name of Noj Peb Caug (“noh pay chow”) for “eat 30” – a call to eat enough for each day of the month at the end of the final month of the year.

Over gigantic coal and propane grills, local joints like the one-year-old Hungry Hippo of Fresno, decades-old businesses, and visitors from other parts of the state and country churned out favorites such as Hmong and Lao sausages, grilled chicken quarters, and sticky rice steamed in gigantic bamboo shoots. Elders and youth ran whole sugarcanes through juicers and tea stands served up milk drinks jammed with rainbow slivers of gelatin.

And, of course, there was qaib vom (“kai vau”) boiled chicken, which many Hmong people also have at home with fresh chickens to accompany hu plig (“hu plee”) soul-calling and feasting with ancestors’ spirits.

Billy Tou Ger Lor, a practicing txiv neeb (“tse neng”), or traditional Hmong shaman, video chatted with AsAmNews from Minnesota after a lot of “unhealthy eating” over the holidays. He said that eating plenty of meat during Hmong New Year symbolizes wealth and wishes for prosperity, going back to the days when meat was a rare luxury in Hmong homelands.

He reported that he had been consuming whole chickens starting in November with families who sought his help in calling for all ancestral souls in their lineage to come back home.

To do this, families prepare a live chicken or sometimes a hen-and-rooster duo, plus nearly 50 to 60 raw eggs to feed everybody. The eldest father calls forth every known ancestor in the lineage before the burning of ntawv nyiaj (“dah-euh nia”) – joss paper money often folded into imitation gold and silver bars – in a special pan.

The shaman slaughters the fowl, asking the souls of the animals to assist in rounding up the ancestors. After feathering, the families blanch the birds with their bodies intact. The txiv neeb looks at how the chicken’s toes curl to predict how the year will go in terms of relationships, business, and obstacles. Hens’ feet predict the fate of men in the family. Roosters’ feet predict the fate of the women.

Lor, who learned how to slaughter a chicken for food when he was four years old, said that some people dip their sacrifices into the boiling water feet first and try to adjust the toes into favorable positions.

“Do what you need to manifest,” Lor shrugged, chuckling.

In the second calling, the family names the ancestors again, inviting them to the table. They send the chicken souls into the incarnate and consume every part of the animal, along with a side of just-boiled eggs.

At the New Year festival, Lao American and Fresno resident Intha Phomkhai recalled her memories of helping her siblings and parents cook at prior Hmong celebrations. She said that vendor stations were not as formalized as they are now. People used to just show up.

At the same time, it still took the entire day before the event’s opening to transport supplies to the site and receive orientations and inspections from food, health, and safety officials.

For Phomkhai and her family, the festival was a changeup from the usual grind of preparing food at a deli behind the Asian Village mini-mall in Southeast Fresno, the struggling neighborhood that became the epicenter of Hmong re-migration within America in the 1980s.

General Vang Pao, who led the Hmong in the war in Laos, resettled in Fresno, where he led the Hmong American community. An elementary school in the city bears his name, and the New Year parade now commences at his statue right on the fairgrounds. The concrete form of a young Pao sitting in the fields was unveiled at the festival of 2013, after his death in the nearby town of Clovis on Jan. 6, 2011.

Once Phomkhai’s parents passed away, also in 2011, she and her siblings stopped working the event. She had not been back to the fairgrounds for five or six years and noticed that 2023 featured a lot more kinds of food, including non-traditional items that weren’t Hmong, Lao, or Thai. Junk foods. Boba tea. Carts with Korean and Mexican influence.

But there was an expansion in traditional food options, too.

Phomkhai said every papaya salad was unique per maker. As if to verify this, several stalls offering seemingly the same thing had long lines that luckily moved fast.

Sitting at a picnic table with an oil-dotted to-go bag of Hmong barbecued pork belly from one vendor and Lao comfort foods from another, Phomkhai pointed out her selections. Pale, little meatballs on a bed of shredded cabbage with a side of sweet and sour sauce. Khao poon red curry chicken broth noodles with pork blood cubes after a difficult choice to forego khai piak sen, Lao chicken noodle soup.

Then, there was khai being, Lao-style eggs-in-the-shell, perfectly skewered on a stick. Phomkhai detailed how the cooks siphon raw egg matter out of tiny holes in the poles of intact shells with a syringe before adding seasoning and piping it all back in, threading them onto a piece of bamboo, and baking them whole.

Beyond the strip of food stands, dry goods merchants toggled fluidly between Hmong and Lao languages, calmly and informatively hawking foods and wares from Laos, Thailand, and China.

Several areas had fresh piles of locally grown roots, herbs, and spices, most utterly mysterious to non-Hmong perusers. Others had handwoven baskets to steam rice and short chilies. Others had irresistible piles of soft, pliable brooms made of thick bunches of dried wild grasses, going for five or six dollars each.

A few vendors of K-pop and Japanese anime paraphernalia also stood sentry on the main concourse, attended by small clusters of young people in Hmong dress and a few non-Hmong people in plain clothes.

One Hmong couple peddled powdered lotus and collagen supplements chock full of dried fruits, nuts, grains, and rose petals that all came to life as a hearty gel with a bit of boiled water. They had a sample center behind all their stacked pastel canisters and did not skimp when luring prospective buyers with tastes of whatever flavors piqued their curiosity.

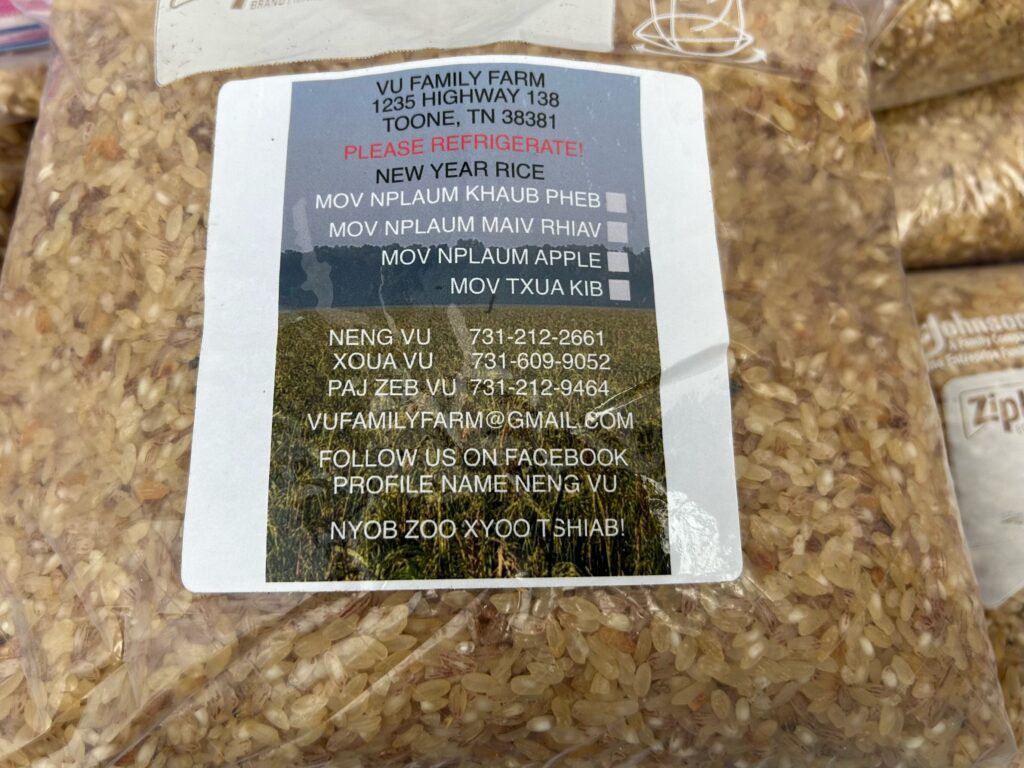

A special area near the exit had new year rice – grains from the first harvest. One of the several uncooked sticky rice vendors was Vu Family Farm from Toone, Tennessee.

Paj Zeb Vu, the elder of the Hmong American family that owns the business, asked in English whether Phomkhai was Hmong. When she said that she was Lao, he kindly exclaimed, “I thought, that’s a pretty Hmong!”

He launched into fluent Lao for his customer, who bought a bag of pre-roasted sticky rice grains.

In a separate encounter, Lisa Lee Herrick, who in 2019 authored a post for BOOM California entitled Eating Thirty in Fresno: Finding Home at Hmong New Year, spoke with Vu’s son, Xoua. She said he explained how to prepare the rice in his slight southern twang.

Finding sticky rice grains from the heartland farm reinforced her impression that the 2023 event had fewer international vendors and attendees but more regional and national vendors to make up for it.

One strain of sticky rice promising a hint of apple flavor caught Herrick’s eye. She was seeking the special rice because she always makes a New Year’s dinner with it, along with a plate of savory Hmong or lemongrass-packed Lao pork sausage, papaya salad, soup with mustard greens, and a condiment made of her aunt’s own blend of homegrown chilies, cilantro, scallions, garlic, and shallots.

Dessert was her mother’s pounded sticky rice cakes, lightly toasted to develop a thin, crispy shell on the outside, leaving a gooey center on the inside. She used to dip them in maple syrup as a child.

“I’d never had rice grown in Tennessee soil before. Rice often takes on the terroir of wherever it’s planted, so imported Thai rice often has a vanilla-coconut nose while rice grown in California lacks those subtropical aromas,” she informed AsAmNews later, in an email.

She remarked that the biggest, most exciting changes she could detect in the Hmong American community nowadays was the steady increase in agriculture, entertainment, creative art, fashion, and textile businesses incorporating Hmong motifs, idioms, folk wisdoms, and clothing. As more Hmong American entrepreneurs enter the open market that exists for these cultural remixes, they find avid support from Hmong consumers.

At the festival, Herrick bought a t-shirt from the Hmong-owned, Stockton-based Eezymade Print. The black-and-white design on the tee had an inside joke any Hmong American would understand. The shirt displayed how to make rice using your finger as a measuring device, with a sidebar about Hmong bride price speculation.

Meanwhile, special programming took place inside the Industrial Education, Industry Commerce, and Agricultural buildings in lieu of one large open-air stage.

People enjoyed live music performances or stepped up to stage themselves in relaxed open mic sessions. Others worked off the food in badminton and volleyball tournaments out on the concrete.

Thao joined an executives-versus-youth match. “I have to tell you the score,” he said, stating that the score was 21-0 in favor of the young athletes, and then 21-1 after a rematch.

“It was nice to play with the young folks – they loved us for that,” he laughed.

In one of the annexes, audiences screamed wildly for numerous groups vying for top place at the two-day-long senior and junior dance competitions.

The inaugural Miss Hmong Grand International pageant, considering Hmong entrants from all over the world, also happened during the New Year festivities.

In the self-design showcase, Paj Lee wore a gigantic semicircle poster board that radiated in an arc over her shoulders. The front was appliqued with pieces of fabric illustrating the Hmong refugee experience. The back featured photos of Hmong veterans and refugees.

Ultimately, the best self-design prize went to Hnub Ci Xyooj, who was also second runner-up for the pageant.

Hnub Ci Xyooj, Nkauj Hli Muas, and Houa Hawj received designations as Miss Popularity, Miss Photogenic, and Miss Congeniality, respectively.

All contestants had to answer the question of how Hmong all over the world could unite.

The first runner-up was Taylor Moua, and the woman to be crowned Miss Hmong Grand International 2023-2024 was Paj Tshiab Xyooj, also the best talent winner and recipient of a $10,000 sum.

An unjudged pageant of a different kind took place all around outside. Regular guests paraded around in a staggering array of traditional dress – potentially, clothing from all 18 Hmong clans, divided into “green” and “white” categories based on colors and patterns of clothing plus type of dialect spoken.

Institutions, bloggers, and forums have loosely likened the linguistic distinctions between “green” and “white” Hmong language to the difference between British versus American English.

Lao, Thai, and Chinese Hmong dress, and everything in between, was also part of the full spectrum of traditional to modern forms of clothing at the fair.

Herrick said that she and many Hmong people have felt unamused or even hurt by non-Hmong/Miao fashion designers or businesses reappropriating Hmong textile designs without attribution for mass appeal.

“Hmong are deeply independent people who value mutual respect, and many handmade textiles and clothing are considered sacred and deeply personal. There is a deep desire to not have Hmong culture flattened and commercialized merely for profit, especially by designers from outside the Hmong community,” she said.

Many other vendors were not appropriating clothing, but sold more economical polyester or printed cotton clothing in place of the hand-woven, embroidered, indigo-dyed hemp of Hmong tribes.

Just so, jewelry stations twinkled with costume jewelry because real silver versions of ethnic jewelry are hard to come by. A lot of the Hmong shoppers made do with these more accessible, affordable representations of their culture and still found authentic items, such as heavy, thickly smocked natural white hemp for funerals.

Xeng Yang, of ProjectX Collections, LLC, was an example of one Hmong American designer who is applying her wildest imagination to traditional clothing and making designs that are more accessible to all, but with attribution.

Born in a refugee camp in Thailand, she came to the U.S. in 1993 and lived in Fresno until she fell in love with someone from Stockton and moved there.

“I never liked Hmong clothes until I got married,” she declared, to AsAmNews.

As the youngest daughter in a family from a clan that wears a black and blue tunic and pants set, she had no one younger than her to dress up. When she married her husband, she learned the joys of dressing up her many younger sisters-in-law for the Hmong New Year.

She was working as a hairstylist and makeup artist with a penchant for photography and was already designing her own clothes for photoshoots. After five years of photography, she decided to design and sell her own creations.

“I want to see people live my fantasy. New trends or any trends, it’s all in my head or mind. I’ll daydream or sketch or research. The eyes and brain will create something crazy,” she said.

Some of her clothing adheres closely to tradition. Other pieces are modern mashups. Yet others render the lavishness of old vintage style in futuristic palettes of neon colors, dripping with translucent beads, sequins, and marabou trimming.

Yang worked hard – she described herself as someone who gives a thousand percent to what she wants to do and believes everyone else must find the one thing they are meant to do in order to be creative and productive.

Her business has rapidly grown into a team of 20 – two in California, one in Thailand, and 17 in Laos, including her sister, who sews every piece by hand.

Together, the workers cross oceans and borders to buy materials – U.S., Laos, Vietnam, China, and Thailand. They drive hours at a time to various cities in search of fabrics and paj ntaub (“pa dao”) “flower cloth,” Hmong hand embroidery or fabric. Yang has yet to go to Laos, though the Laos team members have met her in Thailand before.

She has been a part of the Hmong New Year in Fresno for five years now. “I can’t wait for the new year to come,” she said.

She said that she is glad to have made it through the disruptions of 2020. In fact, more and more women are wearing her designs for cultural events, for vacations, and even everyday wear. She wished the Fresno New Year could go back to being seven days long again because she could not get enough of seeing people dress up.

“I’m very happy seeing others dress in Hmong. I love it. I smile. I will love to see more,” she said when asked how she feels about non-Hmong people wearing her creations.

This year, she is expanding her repertoire of children’s and men’s clothing.

Phomkhai looked through Yang’s collections and asked questions just as she did under other tarps, poring botanicals and elixirs she still did not know about.

“It’s the same country but we have no knowledge. They’re up in the mountains,” she said, incredulously, referring to the distinct Lao and Hmong cultures.

From his vantage point in the Midwest, where the largest Hmong population actually resides, txiv neeb Lor said that Hmong and Lao societies in the U.S. and abroad to have a “very respecting relationship.” He added that the Ambassador’s visit at Fresno’s opening ceremonies was probably a big milestone but that the two cultures have had fluidity for a long time.

He mentioned that Hmong people are on the 1000 Lao kip (₭1000) bill, worth half a U.S. dollar. He also held up his arms to show two red strings tied around his right wrist and one white string tied around his left.

These were from the khi teb (“khi tes”) blessings for good fortune delivered by elders and parents – a migration into Hmong culture and, in different forms, to Thai practices, from Lao baci soul-calling that is rooted in pre-Buddhist animist traditions.

“It’s not very formal and can be personal, very fond, a way to show love,” Lor said, explaining that white was for blessings and red was for protection. Often, the red and white strings are braided together. At the festival, Hmong and Lao alike wore the strings under their cuffs, just like they may have worn real money pinned to the insides of their clothes.

Members of the Lao community in Fresno will have their pi mai, or songkran, new year in April – perhaps local Hmong will join in. But, Phomkhai said, the Lao celebration has always been far smaller than the Hmong event.

“In general, we need to promote our identity more. Lao, Hmong, Khmer are lagging behind. We need to work together to promote ourselves and try to be a resource of our own,” Thao said, reflecting on the first Fresno Hmong New Year he coordinated.

To help in this as an individual, Fresno-based Herrick is working on her memoir with support from the Elizabeth George Foundation. She hopes to publish the book in 2025, the 50th anniversary of the first Hmong exodus from Southeast Asia in 1975.

Her father will be a major figure in the book.

“My father was part of that early first wave, and much of my love for learning and humanity comes directly from him,” she said.

Herrick is also a founding sponsor of the Hmongstory Legacy Project, a curated experience executive produced by Fresno-based graphic designer and HmongStory40 founder Lar Yang. The team is preparing an interactive exhibition of eyewitness accounts and family artifacts that document community impacts and evolutions of the overseas Hmong community in America.

And if all goes well, The Hmong, Inc. will continue with its contract through 2027, running the sort of homecoming experience that Phomkhai, Herrick, Yang, the Hmong students of 1960-1975, and so many others enjoyed.

Thao said he felt confident that next year’s fest will be even better than this first. The group quickly became wise to regulatory specifications and outside insurance requirements that caught the organizers by surprise and almost resulted in event cancellation.

Such debacles were unbeknown to the happy guests, and Thao gave the rather smooth running of programs an “A+.”

The Hmong community has started 2024 excited to continue not only the continued remembrance but also the spread of the labyrinthian Hmong culture into the future.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

Happy Lunar New Year. We are now 40% of our goal of meeting our $5,000 matching grant challenge with less than 8 full days to go. Every donation will be matched dollar for dollar through February 16 up to $5,000. All donations will go toward fully funding an editor position at AsAmNews and to support our reporting. You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.