By David Hosley

A photographer’s vision is peeling back the layers of four Japanese communities in Placer County, where an extraordinary community project presents Japanese American history tied to railroads, refrigeration and hate crimes.

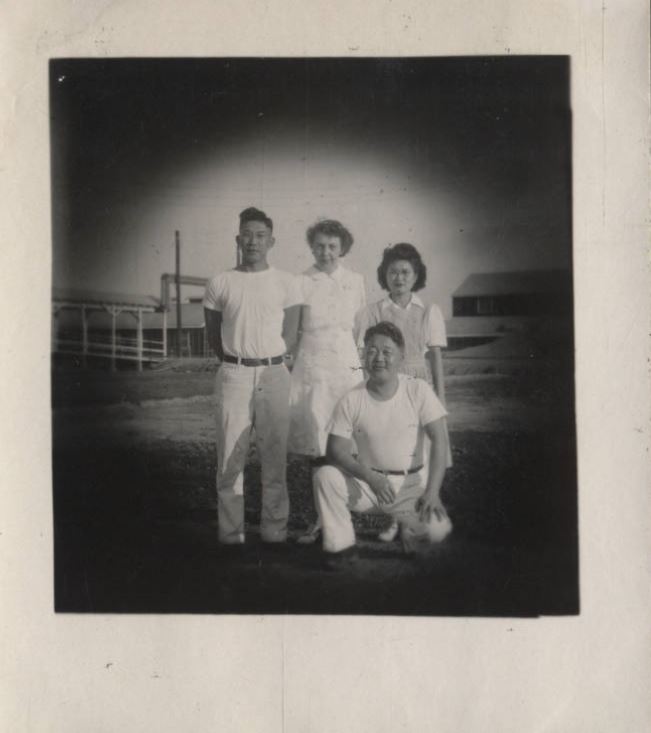

Rebecca Gregg has a unique perspective on the Japanese American impact on Placer County in California’s Sierra Nevada foothills. As a photographer, she has captured images that help viewers understand events of a century ago. She does so by photographing buildings still standing today. Then she matches them with historic black and white pictures taken many decades ago when the county’s towns along the Lincoln Highway had Japanese neighborhoods linked to surrounding fruit tree orchards. The before and after photos reveal where the Japantowns were, and even show some of the people who lived and worked in them.

While the Japanese American population in Placer is a shadow of what it was before World War II, Gregg senses it in abundance. “The Japanese influence hasn’t gone away,” she observed a few years ago at a public forum on the Japantowns of Placer County. “In fact, it’s just gotten wider.”

Her photo project is called Beyond Japantown, and she says the Japantowns that have lasted best in California are ones in historic downtowns. The neighborhoods are still there, even while the buildings’ purposes have changed and the Japanese occupants displaced by government hysteria, its tragic aftermath and modern highways.

A good example when looking beyond the current use is Serendipity, a gift shop at 135 Sacramento Street in Auburn. The building formerly housed K. Tsuda General Merchandise, founded in 1918 and closed in 1942 because of forced removal. Some years after the war, the Tsuda family purchased a Buddhist Church building about a block away and opened Tsuda Grocery, with descendants operating it until 2007. The structure is now a tap room and restaurant. A historical marker about the Tsuda’s enterprises can be seen at Lincoln Way and Sacramento Street in Auburn.

Loomis Mutual Supply Company was one of Placer County’s oldest Japanese businesses. It dates back to the early 1900’s in several locations, but the building today at Taylor and Horseshoe Roads was operated from 1962 by Benji Takahashi and his nephews George and Milton until closed in 1988. It offered everything from milk and meat to blue jeans and boots.

Another building still standing, but with a different use, is located at Taylor Road and Walnut Street in Loomis. For 73 years it was the home of Main Drug Store, opened in 1945 after Hiroshi “Doc” Takemoto and his spouse Tsugie “Rose” Takemoto, along with his mother Kikuyu. Doc and Rose both came from retail backgrounds, as his father owned a pharmacy in Sacramento’s Japantown and she grew up in her father’s grocery store in Penryn where she worked as a butcher. Doc had gotten his pharmacy degree from the University of California’s San Francisco campus in 1940 and went to work with his father before Pearl Harbor changed everything for Japanese Americans.

Main Drug sported a soda fountain, which made it popular with teens, but also the regulars who gathered to catch up on local news and see their friends. Both were active in the community, including Doc being a stalwart member of the Lions Club, and raised their family in Loomis. Their son Gordon became the third generation of pharmacists in 1968. Doc died in 1981 but Rose worked at Main Drug until she was 97, passing away just five years ago at age 102. Gordon and his wife JoAnn closed the store in 2018. It is now an ancillary building for Ace Hardware.

In Roseville, the Roundhouse Deli is now in a building that was a Japanese grocery store. There is a map denoting Placer County Japantowns and key buildings.

Standing Guard

One reason the story of Japanese settlers in Placer County is so accessible is an initiative that Rebecca Gregg and others helped foster as faculty members of Sierra College. Standing Guard: Telling Our Stories was inaugurated in 2002, for the 60th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 which ordered the evacuation of Japanese Americans to incarceration camps. A broad coalition of faculty, students, historians and community members set out in 2000 to document and communicate the presence and impact of Japanese and Japanese Americans in Placer County. Besides Gregg, some of the early supporters of the campus-wide initiative included history professors Lynn Medeiros, Debra Sutphen, Dean of Liberal Arts Bill Tsuji, and local nursery owner Hiroshi Matsuda. The results ranged from a commemorative Standing Guard Remembrance Garden on the college campus and a new history course, to establishment of Sierra College Press, with an initial publication being a book of oral histories featuring local Japanese Americans. Standing Guard: Telling Our Stories sold out its initial printing in four months.

The Standing Guard project has a long tail. Sierra College Press is still a unique entity in the world of community colleges. The garden is an icon of the Rocklin campus. And the oral histories, most of them recorded by students, unlocked some of the silence about Japanese incarceration. Photo albums, museum exhibits, public forums, and videos followed in subsequent years. The mission has broadened to include protection of civil rights for other groups who have been the target of ethnic hate. A writer’s conference marking the 20th anniversary of the book in 2023 featured Maxine Hong Kingston, Paul Tran and futurist Kim Stanley Robinson.

A volunteer offshoot group, Still Standing Guard, is planning another book of oral histories and photographs for publication in 2024. It will also detail the enduring impact of Japanese on Placer County’s history. Still Standing Guard is holding two community events later this spring at Del Pro High School Auditorium in Loomis. On May 11 at 7 p.m., Of Civil Rights and Wrongs: The Fred Korematsu Story will be shown. On May 17 at 7 p.m., a panel discussion is scheduled on Standing Guard: Telling Our Stories.

Third generation Placer resident Julie Hanson appreciates the sustained effort to document the Issei and Nisei. “I love that projects like this happen in our community,” Hanson told AsAmNews. “These people were leaders in our community. They are an important part of our history.”

And what a story there is to tell in Placer County. It is different in a number of ways from Japanese immigrant narratives elsewhere in California, but shares the connectivity to Chinese who came before them and experienced sustained racial bias.

Following in Chinese Footsteps

Japanese settlers in Loomis, Penryn, Newcastle and Auburn arrived in significant numbers well after the impact of the Gold Rush, but were part of a second economic boom driven by agriculture. Chinese workers in Placer County had lived and labored in dangerous conditions in the 1860’s to construct the transcontinental railroad, and after that was done, build other train tracks in the Central Valley and foothills, with Roseville soon a transit hub. Some of the workers became field hands and modified water delivery systems established during the Gold Rush. The water irrigated a burgeoning fruit tree industry, which spread from Loomis at 400 feet above sea level east to Auburn at 1,300 feet elevation. The Placer County towns were all situated on former mining camps, Penryn on Stewart’s Flat and Newcastle on Secret Diggings.

Before 1880, there were only 150 Japanese immigrants in the U.S. That same year also marked the population peak in California of the first generation of Chinese immigrants, who had faced a growing hostility in the state for decades. The Chinese Exclusion Act of1882 prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers for ten years. While a federal measure, it was primarily the result of competition for jobs in the western U.S.

Farmers in California thus needed to replace Chinese workers and looked to Japan for a solution. Japan had reluctantly opened to international relationships in the 1850’s but the Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought further Nippon modernization that drove increased urbanization. It also caused a decline in the vitality of agricultural regions, and ensuing starvation and poverty accelerated migration from southern Japan to America in the 1890’s. A number of sojourners would wind up in the Sierra foothills, just a dozen miles or so from the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony established in 1869 near the site of Sutter’s Mill.

Carving Out A Deciduous Niche

The Japanese immigrants adapted the Chinese labor boss system to tending the orchards of plum, pear and peach trees. The first generation Issei often lived or visited merchants in or near to Chinese neighborhoods in Placer County towns. Men who could speak both English and Japanese and had networks in Japan could recruit workers and also negotiate terms with growers. They prospered as middlemen and even provided clothes and tools needed for farm work, and tips on where to stay.

The railroads opened new markets for California products, and that included crops grown in the Central Valley and Sierra foothills. The first train that carried only fruit crates went east with 15 freight cars in 1886. In 1888, ice was added to some loads, reducing spoilage and enabling produce to go all the way to Chicago. Seattle, Portland and Los Angeles were within reach, too. In 1906, an ice plant was built in Roseville, allowing fruit to be pre-cooled before loading onto refrigerated rail cars. The operation expanded and became the biggest in the country. Japanese also became maintenance workers on the tracks in the region.

By 1910, half of the Japanese population in U.S. was working in agriculture. A relative subset of that workforce was maintaining and harvesting orchards, but in Placer County Nisei dominated agriculture. In 1915, 55 of 68 fruit ranches in the Penryn area were operated by first generation Japanese immigrants, most of them leased.

Increasing Opposition To Japanese

While Placer County was becoming famous for growing fruit that fostered a growing Nisei community, opposition to Japanese had been rising. Anti-Asian sentiment had been transferred in a number of ways from the Chinese to the Japanese newcomers. They were different in culture and language, but that distinction seemed lost on most non-Asians. It may have been more about retaining power in all the ways it can be wielded in a society. A good deal of the leadership on political actions to suppress Issei residents came from the Golden State and was mirrored in measures passed in other states and federal bodies. California’s legislature in 1905 adopted resolution against immigration from Japan.

The Gentleman’s Agreement, an informal U.S. pact with the Empire of Japan in 1907, limited Japanese immigration. A Second Gentleman’s Agreement in 1908 stopped two-step immigration from Hawaii, then a nation. The peak of immigration from Japan was between 1910 and 1924. In 1925, the U.S. Immigration Act halted all Japanese immigration.

A series of alien land laws restricted ownership in California, but had been amended in 1913 to allow short term leasing. An opponent of Japanese land ownership was state senator Ernest Birdsell, who leased orchards to Issei while representing Placer County in Sacramento. In Penryn, 90% of Japanese farmers were tenants.

Some found a path to ownership. Seven Nisei farmers formed Placer Fruit Company and made the company’s manager, who was a U. S. citizen, the owner.

Robust presence in four Placer communities

Western Placer County Nisei farms centered around towns of Loomis, Newcastle, Auburn and Penryn, which had the largest Japanese business district. No orchards were more than five miles from the rail line. Whites owned almost all of the distribution companies, making a living on the mark up from farm to consumer.

A Japanese American Citizen League chapter started in 1928 had grown to 100 members. Thomas Yego was the chapter’s first president, and worked tirelessly to grow JACL as a national organization.

The Japanese Methodist Church founded in 1916 in Loomis was complemented by Buddhist Churches in Penryn and Auburn which had Saturday instruction in Japanese for children whose parents worried that they were losing the language. Similar classes were taught in Newcastle and Lincoln.

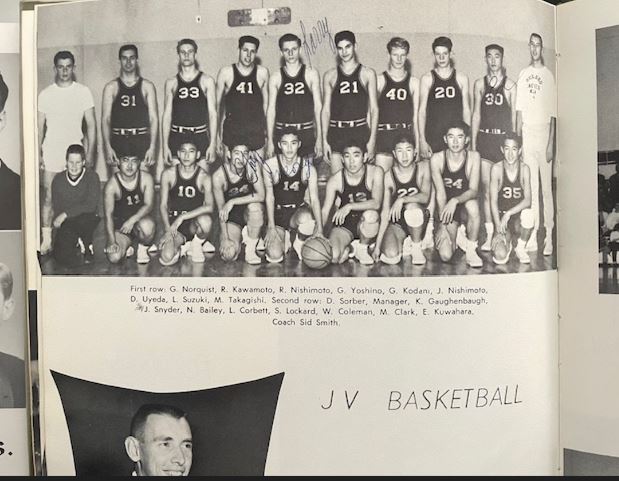

Unlike part of the Sacramento Delta, public schools were not segregated in Placer County, and in some schools during the Depression Japanese Americans were one-third of the students. Half the farms in America in 1935 had no laborers besides the farmer’s family. Everyone worked, including children who had chores before and after school. Half of California’s farms were under 50 acres, a quarter under 20. But even during an economic disaster in the U.S., farm families at least could grow some of their own food.

By 1940, there were about 1,900 residents of Japanese descent in Placer County. With the Nazis waging war in Europe, and tensions with Japan rising, the U.S. began building up its armed forces, including registration for the draft. The Placer Herald reported on July 5, 1941 that 86 young men had registered. Almost half were Japanese Americans.

Pearl Harbor and Executive Order 9066

George Yonehiro was out in the yard of his parents’ home in Gold Hill, outside of Newcastle, on December 7, 1941. A graduate of Roseville High School, he was now attending Sacramento City College, where he was also part of the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Yonehiro recalled he was doing some hoeing, cleaning up the yard, when his sister burst out of the house with the news from the radio about the attack in Hawaii.

At the time, his older brother Horace was on active duty in the Army. George’s father was an Army veteran who served in the infantry in World War I, and an American citizen.

Young Yonehiro went back to his classes, but soon heard that he was prohibited from flying out of Sacramento Municipal Airport. The military had taken over airport operations, so a Japanese American pilot was grounded. Travel restrictions by car, bus and train were also issued by the government, but Yonehiro was still able to go to nearby Sacramento.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which set in motion removal of all those deemed a threat to commit espionage and sabotage in time of war. The three Pacific states were divided into zones for enforcement of the restrictions. Then, Japanese families were asked to relocate voluntarily from a handful of areas. Civic leaders of Placer County were observed to be slow to call for removal of the Japanese American neighbors.

Placer County’s Japanese immigrants and their children were mostly in Zone 1, which included all of the coast, with a smaller number in Zone 2, which included most of the Central Valley. On March 29, 1942, the Army general in charge of carrying out the order issued a proclamation for forced removal of all Japanese and Japanese Americans in the two zones on very short notice. George got a phone message saying his father wanted him to return home.

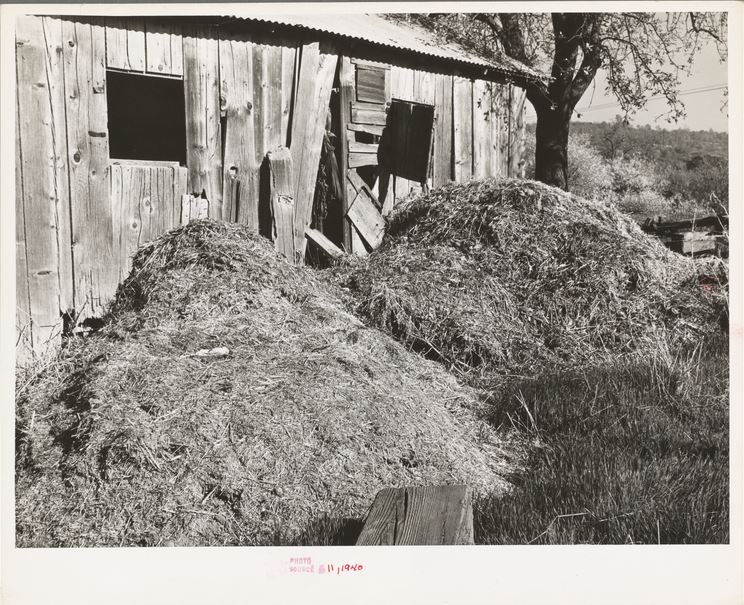

In Placer County, Caucasian owners of several fruit processing and packing companies argued for delaying displacement of local Japanese families until after harvest. It was to no avail. Some Japanese Americans who owned properties came together and incorporated their holdings as Placer Farms and Placer Orchards and named managers to act in their absence. Others individually asked a trusted non-Asian employee or friend to take over. Yonehiro was told to complete the term’s course work. He had six days to do that.

Time was short, and those facing incarceration sold their business and household goods as best they could, sometimes for pennies on the dollar. Treasured belongings were stored in churches, temples, and garages. In an oral history, Frank Kageta recalled he had seven days to pack, putting his goods in the Loomis Japanese Methodist Church for safe keeping.

Dorothy Tsuda of Auburn was a 19-year-old business student in Sacramento when the order was issued. Two of her siblings were studying in Japan, and they would not return until after the war. The Yanehiro family put most of their belonging in an outbuilding, leaving their appliances in the house. Their chickens and food on hand were given to a neighbor.

The initial Placer group to be incarcerated was to report to an assembly center five miles southeast of Marysville on land owned by the Yuba County Irrigation District, starting May 11, 1942. They would be held just a mile from John Sutter’s Hock Farm. Those further east in Placer County made the same 30 mile trip a few days later, totaling about 1,500 from the foothills. They were assigned spaces in one of three blocks, each block with five living areas whose walls did not reach the ceiling.

Construction of the Marysville Assembly Center had started in late March, but spring rains made for delays, and when the Placer groups arrived they found their temporary housing had been built on uneven ground that was muddy. Standing water created hotbeds of mosquitoes, and the pit toilets weren’t dug deep enough and soon filled up. According to oral histories, the stench was overwhelming.

Groups from Elk Grove, Florin and the southern outskirts of Sacramento arrived in mid-May and were assigned to Blocks 4-6, with four other buildings dedicated to medical facilities and recreation. There was no school except daycare. Everyone had to be in their assigned spaces daily at 8 p.m. for a head count. On May 26, 1942, a graduation ceremony was held with 36 teenagers receiving a diploma from their high school principal, and nine graduating from Placer Junior College.

The peak population was 2,451 in early June. At a rate of about 500 a day, the entire group was transferred to Tule Lake Relocation Center the last week of June. Buses took them to a nearby railroad siding where a train was waiting for the 260 mile journey north to just below the California border with Oregon.

Pat Morita Was The Placer Exception

There was one Japanese American left behind in Placer County that spring of 1942. Noriyuki “Pat” Morita was born in Isleton, but developed spinal tuberculosis as a toddler and spent most of the next nine years in medical facilities, the bulk of it at Weimer Institute in Placer County. He spent years in a full body cast, but after surgery on his spine at Shriner’s Hospital, Morita re-learned how to walk in 1943 at age 11, and was immediately transported to join his parents and siblings at the Gila River Relocation Center. After more than a year in Arizona, the Morita family was moved to Tule Lake.

Decades later, Pat Morita broke barriers in Hollywood as a star in The Karate Kid, Mr. T and Tina, Ohara and Mulan. He credited his time in Weimar for helping him develop as a comedian, describing launching spitballs at the sanatoriums ceiling while flat on his back, and using a sock as a puppet to amuse himself and other patients.

Resistance Behind Barbed Wire

Placer County residents of Japanese descent had been forced out from one of the most prized agricultural areas in California. They were now incarcerated in a hostile land. Just a few miles from the place where the Modoc War had been fought in the lava beds, the Tule Lake Relocation Center was east of the lake at about 4,000 feet in elevation. Winters were cold, with windswept snow and rain. Dust and dirt blew through the walls of the 40 hastily constructed blocks of buildings.

The groups held at the Marysville Assembly Center had come together with relative ease. They were farmers, and all had lived in proximity to the familiarity of greater Sacramento. At Tule Lake, they were in the middle of nowhere. And the mix of mostly strangers from the three coastal states compounded the difficult adjustment to loss of freedom and civil rights.

Towards the end of their first winter at Tule Lake, an already difficult existence got worse. The government decided to administer a survey, which was supposed to determine levels of loyalty, including willingness for able men to serve in the U.S. military, and women to serve in auxiliary services. The survey had many questions, a number poorly worded with compound sentences. Many in the first generation of Japanese immigrants particularly struggled to comprehend what was being asked of them. Their children, products of the baby boom between 1915 and 1930, felt torn between their parents’ views and their own as citizens. Officials tallying the survey results put respondents in categories, primarily labeled loyal or disloyal. Forty two per cent at Tule Lake refused to answer the survey questions or replied “no” regarding entering military service and renouncing Japan. It was the most negative response of the 10 facilities.

Feelings ran hot. There were strikes and demonstrations. The government cracked down, renaming the facilityTule Lake Segregation Center, and sending many of the 4,000 deemed loyal to other incarceration locations while bringing in “no-no” respondents from the nine other facilities. Most of the Placer County group were sent elsewhere. Dorothy Tsudo from Auburn went first to the concentration camp near Jerome, Arkansas and then Gila River in Arizona. Her father was sent to the Fort Lincoln Detention Center near Bismark, North Dakota, a holding place for Tule Lake dissenters. Some others from Placer went to Heart Mountain, Wyoming, which had numerous “no-no”s heading to Tule Lake.

Wartime Handling Of Evacuee Property

For the Japanese American owned farms and ranches in Placer County that had not been placed into a protective corporation that could manage them, the U.S. Farm Security Administration sought replacement farmers in the spring of 1942. It wasn’t an easy recruitment, but by June the agency reported the operations of 856 Placer farms had been transferred. The new operators got half the proceeds of the harvests, a windfall since fruit and grapes had the highest value of all the crops in the state and the new operators had been in place for just a few months.

For those incarcerated in the concentration camps release was possible, especially for younger adults. Dorothy Tsudo was able to attend cosmetology school in Chicago and got a job as a hair dresser, for instance. Volunteering for U.S. Army became an option, if the draft didn’t get you first. Besides the Army units that would go on to fight in Europe, fluent Japanese speakers could join the Military Intelligence Service, which provided further language training in preparation for translation and interrogation roles in the Pacific theater. The majority of former Placer residents still incarcerated were released in January,1945, long before the Tule Lake concentration camp closed in the spring of 1946.

Arson and Attempted Firebombing

Anti-Japanese American sentiment had continued in Placer County, and California, even when American citizens of Japanese descent and their parents were removed.

In 1942 the county registrar of voters had purged from the rolls of eligible voters all who hadn’t voted in the previous primary and general elections They would have to re-register. So a number did while imprisoned at Tule Lake, with 130 voting by mail in the 1942 fall general election.

A hospital was built in Auburn for the U.S. Army in 1943. It was named after General John DeWitt, who had recently been replaced as head of the Western Defense Command, his role in the incarceration destined to be cast in controversy. Patients began arrived at DeWitt Hospital in spring of 1944. Ironically, some were injured Japanese American veterans of the Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Soldiers convalesced there as the war came to a close. Later, the complex became a mental health facility, and then Placer County took over the site.

In 1944, the Placer County Board of Supervisors expressed that it “unqualifiedly opposes the return to California of all Japanese, both alien and native born, excepting those in the armed services.” Other northern California city and county bodies passed similar resolutions. The Placer County Citizens’ Anti-Japanese League was also founded. The San Francisco Chronicle wrote that 300 residents of Auburn had signed a petition vowing to avoid fraternization with those returning from incarceration, and a shoe store owner posted a sign saying “No Japs allowed to trade here.”

One of the first Nisei to return to his family’s home was Army veteran Sumio Doi, who had fought with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Italy. Two of his brothers were still in the military. He got a sobering greeting as his family was resuming agricultural operations. A local bartender, 38-year-old James Watson, along with two brothers, 20-year-old Alvin and 18-year-old Elmer Johnson, decided to destroy the ranch’s packing shed. The Johnsons were Army privates at the time, absent without leave. On January 17, 1945, five gallons of gas were poured on the shed and lit, but Doi was nearby and put out the fire with a hose. The next night, three bullets were shot into the building.

On January 19th, using nine sticks of stolen dynamite, a third attack was made but the fuse went out before ignition. Charged with conspiracy to possess dynamite, and illegal possession of dynamite, the trio’s Roseville lawyer Floyd Bowers presented a defense focused on retribution for Japanese war crimes. In his closing to the jury, Bowers stated: “This is a White man’s country. Let us keep it so.” Unanimous acquittal by an all-White jury was the outcome. Bowers went on to be elected a Placer County Superior Court judge.

Eight bills were introduced in the California legislature in 1945 to prohibit Japanese American land ownership. In the summer, the legislature placed Proposition 15 on the 1946 ballot to enshrine the existing Alien Land Law in the state constitution. Approval was advocated by the California Chamber of Commerce, Native Sons of the Golden West, Native Daughters of the Golden West, California Grange and the California Farm Bureau. Opposition was led by the Japanese American Citizens League and ACLU. The measure lost in the November election by 300,000 votes out of a total of about 1.9 million. Real estate covenants denying ownership to Japanese and other Asians lasted until 1948. The state’s Alien Land Law wasn’t repealed until 1956.

Most of the first generation returned to their Placer County communities, and many of the second generation, too. Those who owned land felt it was their best economic choice. Lila Yamamoto Sasaki of Rocklin said in an oral history that Gene Fowler had been caretaker of her family’s ranch, and he had made sure all of their stored possessions were intact when they returned home. Others took temporary shelter while they waited for leases on their farms to expire, or looked for other work in the area.

Education and Employment Opportunities Post War

The social upheaval in the first half of the 1940’s changed the world, including the United States It also transformed the Japanese American community in countless ways. For the first generation, the Issei, most emerged as senior citizens with their children, the Nisei, now adults who in many cases had sought work or an education away from the West Coast, or served overseas in the military. As Dorothy Fuji said in an oral history interview, “A lot of Japanese families lived in ranches up here, but after the war, they didn’t come back.”

The elders had trauma, often unspoken about, and many lost a way to make their living. Those who were in the first wave of immigrants in the early 1900’s were worn down by the hard life and subsequent loss of freedom. Family structure had been fundamentally changed during incarceration, with newfound freedom from parental control.

The younger generation had some doors opened as the military further integrated, the interstate highway system started to be built, which increased mobility, and the government stressed equal opportunity in hiring at the federal level. Suburbs grew at the edges of big cities, sending echoes of a growing Sacramento population into the Sierra foothills.

Sierra Junior College, started in 1936, remained a place for local high school graduates to access higher education. In 1947, Sacramento State College opened on the site of Sacramento Junior College. A new campus was built in 1951 on a former hops farm and peach orchard in south Sacramento. Top Placer students could attend the University of California, which a number of Japanese Americans did in the 1950’s and 60’s. War veterans could use the GI Bill to pay for college, as well as provide financing for housing.

But immediately after the war, it was a mix of the familiar and rapid change. Fruit trees needed to be pruned, commercial relationships confirmed, and Boomer families begun. Japanese American Citizens League members came together once again, churches and temples held services. In 1946, Placer County reported 176 Japanese voters in the general election. In 1950, 276. Vocations listed for those voters included farmers, ranchers and housewives. More voters would come in 1952 with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Issei were finally allowed to become naturalized U.S. citizens, including George Yonehiro’s mother.

The interstate transportation system championed by President Dwight Eisenhower further transformed Placer County. Enacted in 1956, the initiative aimed to build 41,000 miles of highways across the country. Mostly following the route of the Lincoln Highway through Placer County, the project increased vehicle access from the Central Valley, Bay Area and Nevada. In 1958, Newcastle’s Japan Town was leveled to make way for U.S. 40. It’s successor, Interstate 80, extended the opportunity in the 1960’s for people to live in Placer County and work in Sacramento and other cities to the west.

New businesses were formed, including rancher Sam Ikeda’s partnership with another local fruit grower, Everett Gibson. They built a fruit stand along the new Highway 40 in 1950. When Gibson stepped aside, Sam and his spouse Sally put their family’s name on the business, and their sons joined in later on with new ideas for products and marketing. When Interstate 80 was established, Ikeda’s became a favorite stopping place for travelers hungry for a hamburger or fruit pie.

The decorated heroes from WWII were profiled in a 1951 move, Go For Broke, in black and white. By then, the war vets in Placer County had also benefitted from the G.I. Bill’s financial help with their educations, or buying a home. As the Boomer years went on, observed one community leader, the fruit trees increasingly gave way to roof tops as new housing sprang up.

George Yonehiro was one of the last born and raised Japanese Americans to return to Placer County. He had served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and received a Bronze Star before returning to Chicago and then Colorado. Along the way he attended law school. When his Midwest employer asked him to look into land development opportunities in California, he thought Placer County was just the place. In 1964, he successfully ran for a judicial office and later won elections to Municipal Court and then Placer County Superior Court. He kept a framed poster on his chamber walls which ordered him and others of Japanese heritage to report for incarceration in 1942.

Julie Hanson compares the yearbooks for her mother’s years at Del Oro High School in Loomis in the mid 60’s and her’s at the same school two decades later. The decline in the percentage of Japanese American students is significant. “It looks about 15%” for her mother’s time. For her years in the 80’s, “just a handful.”

In the 2020 decennial census, 1% of the Placer County population was reported to be of Japanese descent.

Support our June Membership Drive and receive member-only benefits. Help us reach our goal of $10,000 in new donations and monthly and annual donation pledges by the end of the Month.

We are published by the non-profit Asian American Media Inc and supported by our readers along with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.

Thank you David Hosley for this amazing series of Lost Japantowns in California. Your writing and detailed research brings lost history to life. Looking forward to more!

Thank you AsAm News for providing a platform.

My shipmate, Howard N, from my Navy days has been gracious enough to share the history of Japanese positive influence in Sacramento and the surrounding areas. Shared with the positives, he has shared the disruption, and in more than few cases the destruction of families, personal & business ! We owe our respect and thanks to the entire Japanese American community for not just packing up and leaving. We are a better Country because they didn’t.