By Raymond Chong

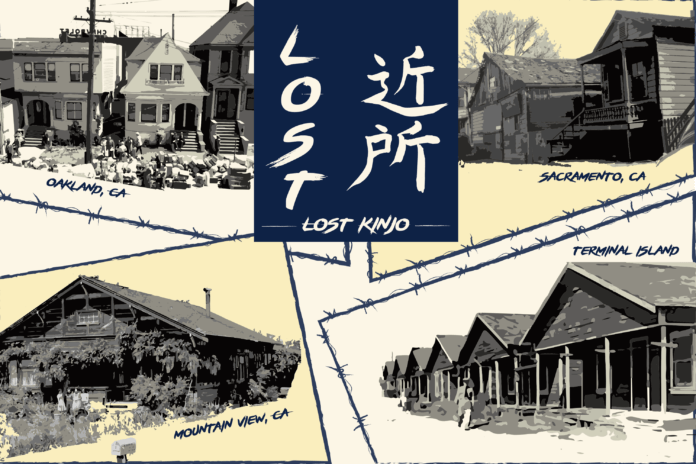

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II not only disrupted their lives and violated their constitutional and civil rights, it destroyed their neighborhoods.

Historian Raymond Chong will share stories of the more than 40 communities that disappeared after WWII during an 8-city speaking tour that begins Sunday, May 5 in Oakland.

Lost Kinjo is a year-long project of AsAmNews funded by the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.

It’s the forgotten history of the Lost Kinjo – The Lost Japantowns in California. Audiences will hear about the systematic discrimination, scapegoating, intimidation, appropriation, segregation, exclusion and dehumanization of Japanese Americans in California.

From 1890 to 1942, the Japanese Americans, Issei and Nisei, thrived in the Japantowns,

aka Nihonmachis, across California. Every Japantown was a social and cultural center

with its activities and events. The businesses catered to their needs for services and

goods in their segregated world.

In today’s American society, other Asian American, African American, Latino, and Native

American communities are under threat through gentrification and are in danger of vanishing too. We will connect the neighborhoods’ impact on cultures and livelihoods in the context of civil rights,

similar to the lost Japantowns in California.

The White oligarchy engaged in legalized but unconstitutional discrimination against the Japanese Americans:

1880 – The California state legislature amended the miscegenation law under

the Civil Code to prohibit the issuance of a marriage license to a white person

and a “Negro, Mulatto, or Mongolian.”

1894 – A United States district court ruled that Japanese immigrants could not

become citizens because they are not “a free white person” as the 1790

Naturalization Act requires.

1906 – The San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution to segregate

children of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean ancestry from the majority population.

1908—Japan and the United States agreed (Gentlemen’s Agreement) to halt the

migration of Japanese laborers to the United States. Japanese women are

allowed to immigrate if they are wives of U.S. residents.

1913— The California state legislature passed the Alien Land Law, forbidding “all

aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land. This later expanded to include

the prohibition on leasing land as well.

1922 – The United States Supreme Court ruled on the Ozawa case, reaffirming

the ban on Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized United States

citizens.

1924 – The United States Congress passed the Immigration Act, effectively

ending all Japanese immigration to the United States.

1942 – President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing military

authorities to exclude civilians from any area without trial or hearing. The order

did not specify Japanese Americans – but they were the only group to be

imprisoned as a result of it.

From late spring to mid-summer, * will speak at eight

venues in California. At every venue, I will expand the speech to cover the unique

Japantowns in the region.

The talks are free; however, you are encouraged to register in advance. Scan the QR code to register or email [email protected].

Oakland, Buddhist Church of Oakland, Sunday, May 5, 2024, 2:00 PM

Fresno, Chinatown Fresno Foundation, Saturday, May 18, 2024, 1:30 PM

Sacramento, Sacramento History Museum, Saturday, May 25, 2024, 2:00 PM

San Jose, Japanese American Museum of San Jose, Saturday, June 15, 2024,

1:30 PM

San Mateo, San Mateo Japanese American Community Center, Sunday, June 16,

2024, 1:30 PM

Los Angeles, Japanese American National Museum, Saturday, July 13, 2024, 1:30

PM

Guadalupe, Guadalupe Veterans Memorial Building, Sunday, July 14, 2024, 1:30

PM

San Diego, San Diego Central Library, Saturday, August 10, 2024, 1:30 PM

In crafting his Lost Kinjo speech, Chong discovered many remarkable aspects of the

Japanese American experience in California:

The White authorities segregated several Japantown and Chinatown “on the

other side of the tracks” along the Southern Pacific Railroad Company tracks to

separate the Orientals from the White population.

The “Picture Brides Era” (1908-1920) resulted in marriages for the male Issei

pioneers and the subsequent boom of the Nisei generation. The Japantowns

changed from catering to a bachelor society to a family society.

The Japanese American farmers successfully grew vegetables, fruits, and

flowers in the Central Valley and California Coast valleys. The White agricultural

industry viewed them as a threat. Because of the California Alien Law, most Issei

farmers only leased their farms as sharecroppers.

During the settlement from the concentration camps after 1945, the White

majority viciously crushed the returning Japanese Americans with their ugly

hostility and harassment in Lompoc Japantown in the Santa Maria Valley.

Given the current climate of hatred in America, the Asian American Native Hawaiian

Pacific Islander community must be vigilant to protect their American civil rights. We

have recently seen the Presidential Executive Order that banned Muslims from

immigrating to America, the State of Florida Alien Land Law against the Chinese, and

the Siskiyou County California ordinance that banned the delivery of water to Hmong

farmers.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana (1905)

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

I recently attended a memorial tribute to the Japanese pioneering Winters,CA.The w

Winter’s Historical Society sponsors a nice local museum recognizing the contributions of the Japanese to the areas agricultural cornerstone. A memorial plaque was installed,at the site of the former “kinjo”, located at the railroad tracks where the Chinese also preceded this community, eventually being mysteriously burned as was the Japantown during the evacuation. The local cemetery also had a Buddhist shrine installed. curiously I would think these cemeteries, mostly segregated, are an open source for future research as many towns in the West had established communities but no longer standing except for the buried descendants.