by Helen Zia

This essay was first published on the Vincent Chin Institute’s website.

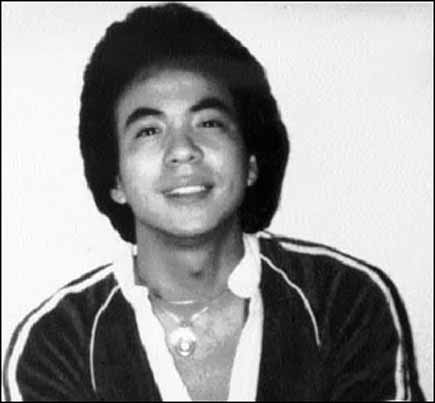

June 23rd marked another year since Vincent Chin was slain forty-two years during a terrible economic recession and an intense climate of anti-Japan, anti-Asian hate. Then, Vincent and other Asian Americans were blamed and scapegoated for the collapse of the American auto industry and the massive layoffs in Detroit.

BIG NEWS: Without explanation, the FBI also chose this week of remembrance to unload a batch of its 40-year old Vincent Chin case files:

I remember every bit of the time covered by these 602 pages, as well as so much more that isn’t in those documents. These documents revisit the information here on vincentchin.org and more definitively in the Vincent Chin Legacy Guide.

If you peruse the FBI files, you’ll read how, on June 19, 1982 in Detroit, 27-year old Vincent was out on his bachelor party at a sleazy bar, celebrating his upcoming wedding, only days away. How he was with three good friends: two white pals, a coworker Bob and Gary, his best friend since first grade; also his Chinese Canadian friend Jimmy.

How a white autoworker–a plant supervisor seated nearby with his stepson–reportedly directed racial slurs and obscenities at Vincent, saying, “It’s because of you mother—s that we’re out of work,” as though speaking his fellow autoworkers.

How Vincent stood up for himself to fight his harassers—who then stalked Vincent and his Chinese friend Jimmy, while ignoring his two white friends. How they crept up on the Asian Americans and fatally beat Vincent’s head in with four “home run” swings of a baseball bat. How the slaying, in front of a busy McDonald’s on Detroit’s main drag, was witnessed by dozens of people and two moonlighting cops.

If that wasn’t tragic enough, nine months later, the sentencing judge in the majority Black city of Detroit, looked at the two white defendants, and declared, “These aren’t the kind of people you send to jail,” and released them with probation and court fines—not even the funeral costs. They never spent a day in jail for beating Vincent to death with a baseball bat.

The 602 documents offer a snap shot and partial view of what the FBI was looking into as the Department of Justice investigated a possible civil rights prosecution. There’s some correspondence from community and Congressionals such as Senator Carl Levin. Missing are the inquiries by Congressmen Norman Mineta and George Crockett and many others, but this is only the first batch the FBI is releasing.

The FBI documents don’t include any of the Wayne County criminal proceedings, the noted failures to interview key witnesses such as the police on the scene, or the mistakes by the prosecutors, such as undercharging the killers and then failing to show up at their sentencing.

The FBI documents also don’t show the considerable efforts of the Asian American community to get the sentencing judge to meet with us. Or how, after weeks of requests, he finally allowed us to come to his courtroom and his first question to us was, Do you speak English?—as though we would show up and not know how to communicate.

Here’s what they do show: there are many scanned pages of the FBI investigator’s handwritten notes. Most are illegible notes and redacted, as are the other FBI internal documents. I didn’t remember the FBI’s meetings with some potential witnesses, such as the killer’s ex-first wife. Interestingly, there’s a short article (page 44) that mentions the often overlooked detail of how court psychologists and probation officers recommended jail time and psychiatric treatment for the killer, whom they assessed to be an “extremely hostile and explosive individual” with “uncontrollable hostility and explosive acting out.”

I found no “Ah-ha” files. However, among the documents are many media reports from local, national, even some international coverage. Reading these news chronicles together reveals how those entirely white and male print reporters simply did not/ could not grasp the concept of anti-Asian prejudice.

It’s truly a throwback in time to see the contemporaneous reports presented in an organized, mostly chronological manner. I was press secretary and later president of the Asian American efforts back then, struggling to get coverage that humanized our communities.

Looking back, I know why those reporters didn’t even bother to ask questions that might have opened their eyes to the existence of anti-Asian hate in the 1980s. It’s because they couldn’t and didn’t see us. We were that invisible to them and to American society at large. They didn’t even try.

Even today, Asian American communities are fighting, state by state, to get an iota of Asian Am curriculum taught in K-12 schools. Then and now, the miasma of ignorance surrounding Asian Americans is filled with the harmful stereotypes of the perpetual foreign enemy or the loathsome model minority.

The FBI files show the steady flow of articles by different reporters that always manage to cast doubt on how a “bar room brawl” could also have involved racial animus. They often wrote how they questioned that race was an issue—yet not one tried to answer their own question by asking Asian Americans how we experience bigotry. Instead, they selected facts that fit their bias.

For example, the first civil rights trial put Vincent’s three bachelor party friends on the witness stand. Two testified that they overheard racial slurs directed at Chin before he got out of his chair and pushed the older white assailant; but the headline predictably chose to throw shade (document p. 291): “Vincent provoked the fight, friend says at Chin trial.” The report didn’t ask why a groom-to-be, at his own bachelor party, would jump out of his chair to push a stranger if he wasn’t provoked.

I remember all of those reporters, especially the elder “alpha” court reporter from the News who wrote an unsigned op ed piece at the end of the first civil rights trial (document p.327). In it, he argued: Well, of course a belligerent drunk will use racial or anti-Semitic epithets toward a Black or Jewish person—that’s not racism or anti-Semitism because what else would you call them, he asks? If someone is overweight, you call out, “Fat Boy.” Of course, you would use Asian pejoratives against an Asian person–that’s not racism, according to this particular reporter.

The news clips in the FBI files show how other reporters’ views of the civil rights cases were influenced by that elder alpha court reporter. Not one of those many articles in the FBI files ask why the killers targeted Vincent—and his one Chinese friend, who was not involved in the fight. Not one of those reporters ever asked why the killers didn’t bother with Vincent’s two white friends who were there, same as Jimmy, the Chinese friend.

The documents also show how a local man testified that the defendants paid him to “get the Chinese guys.” Plural. The documents show testimony from the two officers, Cotton and Gardenhire, who witnessed the attack and testified that the attackers were intent on assaulting Jimmy; they had to order Ebens several times at gunpoint to stop (you can also find their video about this on the web).

The FBI files reveal how white reporters, FBI investigators, the lawyers in the federal case were all focused on what racial words may or may not have been said. Yet, significantly, they never asked or speculated on what words exist that could possibly indicate anti-Asian hate. Instead, they disregarded all the words that witnesses did report hearing.

Even today, with the huge pandemic of anti-Asian attacks that accompanied COVID hate, I’m sure that few non-Asians can think of any anti-Asian words that they would associate with the “n” word and its anti-Black racism.

These 602 files show that the FBI never explored how hate incidents and violence can take place without a single word being uttered. Nor did the court reporters, even though every marginalized person knows this to be true.

On June 23rd, Vincent Chin died from the four home-run swings of the Louisville Slugger baseball bat, Jackie Robinson edition, that his killer slammed against his head forty-two years ago. The 602 FBI files released this commemoration week offer many lessons about bias and prejudice, both unintended and deliberate. Read them with an inquiring mind and the question that still confronts us today: how to end bigotry and hate violence to create the beloved community where everyone can celebrate an upcoming wedding and live together with full human dignity for all.

Vincent Jen Chin: Rest in Peace. Rest in Power.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

Happy Lunar New Year. We’re almost there. We are now 69% of our goal of meeting our $5,000 matching grant challenge with less than 6 full days to go. Every donation will be matched dollar for dollar through Sunday for up to $5,000. All donations will go toward fully funding an editor position at AsAmNews and to support our reporting. You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.