By Yiming Fu, Report for America corps member

When the house next door went up in flames, Michele Lincoln’s husband screamed “you’ve got four minutes to get out!” She didn’t have time to pack anything up and instead went through each room in her house looking for her cat.

Unfortunately, she couldn’t find her cat and left only with her dog. To escape last August’s Lahaina fires, Lincoln drove straight into the fire, through smoke and flames hot enough to melt cast iron. She repeated a bible verse over and over to safety.

“Even though we drove through smoke and flames and lost everything, we made it out with the clothes on our back,” Lincoln said. “I do not have nightmares about that at all. I do have nightmares that we’ve rebuilt and the fire comes back.”

Lincoln is not alone. Many fire survivors rebuilding after the August 2023 fire feel frustrated with the lack of fire prevention efforts. Lahaina residents in neighborhoods that avoided the fires feel unsafe. They think they could easily lose their homes or schools should another fire spark up.

Wildfires are not an anomaly in Lahaina. A fire in 2018 burned about 25 structures. Another fire in 2022 went up over the mountains, avoiding the town. Lahaina is hot and dry and remains at extreme risk for wildfires.

The landscape is characterized by steep slopes, rough terrain, strong trade winds and highly ignitable invasive grasses. The August 2023 wildfire was sparked by a faulty electric pole that ignited on unkempt grasses and was fanned throughout Lahaina by high winds, burning 2,170 acres and impacting 65% of the properties in Lahaina.

Fifteen months after the August 2023 fires, residents say the possibility of the next fire is nerve-wracking. And they have not seen enough fire prevention measures or changes in their communities to reassure them.

Bubbling frustration

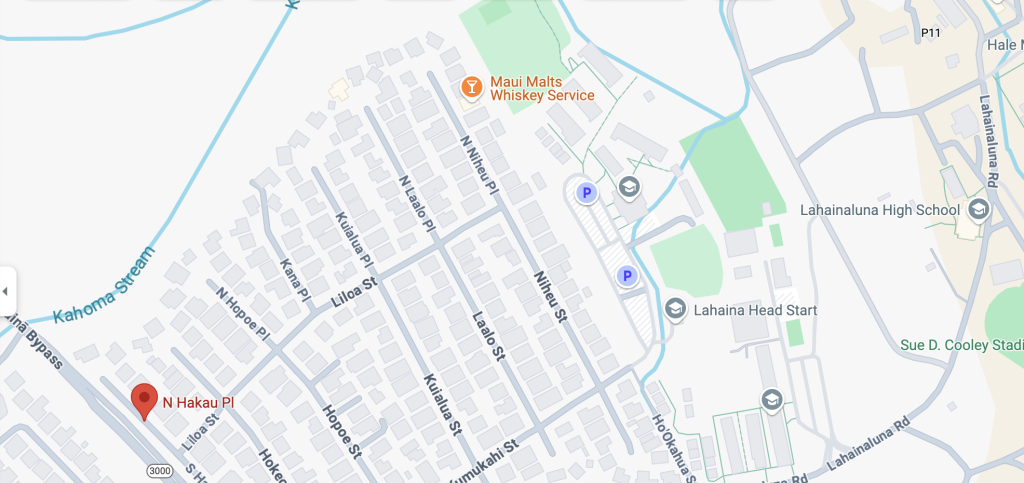

Josephine Quesada lives on Hakau Place, in one of the neighborhoods off Lahainaluna Road that did not burn in the August 2023 fires. Quesada, who retired in 2017, is an immigrant from Manila. She’s lived in Lahaina since 1984, when she and her husband bought the house on Hakau Place that she still lives in today.

Quesada scrubbed toilets at the Royal Lahaina for more than 30 years to support her four children. She has one lung and limited mobility in her knee, meaning she often needs a hand to hold to walk around.

Quesada doesn’t think she’ll survive if fire strikes again. Just above the Lahaina Bypass, Quesada’s neighborhood includes six parallel streets to the highway that all share one exit to the main road. She estimates there’s more than 400 houses in the neighborhood, and most houses have three generations of families living in them. Cars line both sides of the narrow streets, turning most roads into one-ways.

“No one can move!” Quesasa said. There’s no way out. No way in. We’re stuck. We cannot move.”

Quesada’s neighborhood just barely avoided the 2023 fires. She remembers watching the flames dance against the stone wall in front of her home. She packed a bag of her husband’s clothes, threw a bag of rice into their truck and was ready to leave.

While their house didn’t burn, her roof blew off, solar panels blew away and water was leaking everywhere in her home.

“Every time I smell smoke, I panic,” Quesada said. “I’m traumatized from what happened.”

Lack of urgency

The County of Maui has fire prevention plans. In the first draft of the county’s long term recovery plan, there is a project titled Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation. The plan, which is called a “living document” and can be changed with resident input, calls for a multiagency approach to establish a green break or fire break.

A fire break is a strip of land without combustible materials and/or a green break is planted with fire-resistant plants to slow the flames. Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation is categorized as a “mid-term” project, which means it will take 3 to 5 years to complete.

But many Lahaina residents are tired of plans and want action. Rick Nava is the president of the Rotary Club of Lahaina, Executive Director of the West Maui Taxpayer’s Association and Chairman of the Board of Maui Chamber of Commerce. He was born in the Philippines and moved to Lahaina in 1970, where he has lived ever since.

Nava thinks the timeline for fire prevention is too far out.

“Fire prevention, it shouldn’t even be a short-term goal,” Nava said. “It should be an immediate goal. The fire could happen today. The fire could happen yesterday.”

Lincoln is similarly frustrated with the long-term recovery plan putting fire prevention at a three-to-five-year timeline. She understands the whole project would take three to five years for completion, but she thinks the county should have started last year after the fire. Lincoln said she usually tries to be understanding with her feedback, but she was critical in her feedback for the recovery plan.

“We’re rebuilding now,” she said. “It’s not acceptable to say we’ll deal with that three to six years from now in your long-term plan. I wrote ‘are you waiting for all the schools and rest of the residences to burn down before you actually do something?’”

Lincoln has been advocating for fire prevention since 2014. She attends every meeting she can and writes letters to newspapers and local, county, state and federal officials to pump recycled water up to support agriculture and nourish the dry grasses in Lahaina. This idea would bring lush green spaces and prevent Lahaina from burning as easily. Twelve months before the 2023 fires, she sent three letters to the editor advocating to get recycled water for green breaks.

Similarly, Quesada has been advocating for exits in her community since 2014. There is a second exit gate a couple yards from her house. But it’s been locked by Maui Police Department. Residents can call the police to open the gate, but she doesn’t think there’ll be enough time for the police to come open the gate in an emergency.

She’s written letters to her representatives and met with Hawaii State Sen. Angus McKelvey outside her home to share her concerns. But nothing ever happened.

“I go because I’m the only one,” she said. “There’s nothing we can do. I feel like I’m just a piece of stick working myself against a brick wall. I cannot do anything.”

Lahaina’s Filipino community doesn’t often speak up, Quesada said, because they’re more focused on their day-to-day lives and supporting their families. She hopes the future generations will be able to advocate for their hometowns.

The ideas in the long-term recovery plan are not new. West Maui’s Community Wildfire Protection Plan from 2014 recommends vegetation management coordinators, utility company adherence to fire prevention standards, greenbelts and native reforestation to create fuel breaks.

AsAmNews asked the County of Maui and MPD about fire prevention measures implemented since the 2018, 2022 and 2023 fires. The county did not respond to multiple inquiries before deadline.

Community Solutions

Lincoln says she doesn’t really love warm weather. And she doesn’t stay in Lahaina for the “vacation paradise” image either. Instead, she said the town is special because of its people, who are among the warmest and friendliest in the world. She loves Lahaina’s rich history and diversity, where residents of different backgrounds share cultures, overlap and intermingle.

To keep her community safe, Lincoln’s short-term fire prevention ideas include a controlled burn, setting up grazing fields for livestock, getting irrigation and planting bananas or other moisture-dense plants to stop the fire. She also knows of groups that have begun to plant native trees along the mountains and would love to see a Native plant nursery in Lahaina.

Nava, who would often go to Quesada’s house after school, said homeowners should have a key to open the gate. He also said the street congestion in Quesada’s neighborhood could be tough to deal with. The county plans to widen some roads, but he suggests the town enforce parking on only one side of the street and provide consistent and reliable public transportation so residents don’t depend on cars to get around.

To make Lahaina feel more safe, Nava would like to see officials clean up dry grasses, switch the old wooden utility poles to concrete or run the electrical wires underground. While opponents to undergrounding utilities say it’s too expensive, could take too much time or would risk tunneling into sacred Hawaiian land, Nava said time and money should not be barriers when lives are on the line.

“Don’t put money in front of lives of people. We lost 102 lives in this fire. Now we’re going to do the same thing and pray it won’t happen again.”

Lincoln adds that underground utilities wouldn’t have to be everywhere. Electric companies can put them in areas where fires tend to start.

She knows the county has been making progress in the background, but that’s not enough for people to feel safe. Lincoln said she understands why a green break takes time. It’s hard to plant without water, and piping the recycled water up the mountain will take time and money. Still, that’s not an excuse to delay.

“They always say it’s so expensive,” Lincoln said. I’m like so is rebuilding a town.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. A big thank you to all our readers who supported our year-end giving campaign. You helped us not only reach our goal, you busted through it. Donations to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews are tax-deductible. It’s never too late to give.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.