By Jeanne Mariani-Belding

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo– a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

There are defining moments in time when racism stoked by fear, ignorance and intolerance change the course of history—they also indelibly change the trajectory of lives.

For Japanese and Japanese Americans living in Vacaville prior to World War II, their lives changed almost overnight. After the war, their forced incarceration, and with a strong current of post-war racism in Vacaville, most chose not to return.

It was a seismic shift for a once-thriving community who made up a quarter of the town’s population at the time.

By the late 1800s, Vacaville was emerging as a force in agriculture, largely fueled by Japanese immigrants who were sought after to help harvest and grow fruits and crops that fed large swaths of the country. Vacaville is considered the birthplace of Japanese agriculture in California, at a time when Japanese farmers produced roughly 40 percent or more of the state’s agricultural crops.

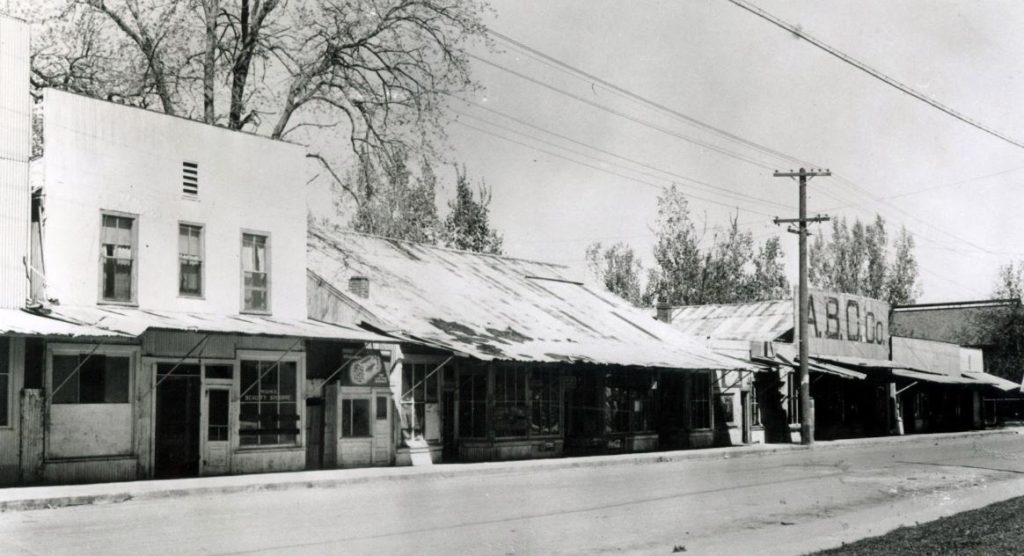

Japanese in Vacaville also planted deep roots in their community. They started their own farms and business, sent their children to school and church, and developed a thriving Japantown along Dobbins Street. Vacaville’s Japantown included a popular candy store, restaurants, barber shops, a Japanese language school, and a Buddhist temple, referred to by locals as the Buddhist Church. From 1936-1941 about one-third of Vacaville High School’s graduates were of Japanese ancestry. They were also some of the school’s top scholars, artists and athletes.

“It was a very robust Japanese community,” said Elissa DeCaro, president of the Solano County Historical Society. “Vacaville became a cultural hub for their community. Not only was this a place of worship, it was also a place to celebrate their customs and traditions. We are halfway between Sacramento and San Francisco, so we were a natural stopping place. We were known as the Tokyo of the West.”

All that would change, almost overnight.

Shortly after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese Americans quickly became targets of racist hysteria. That hysteria culminated in February of 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcibly imprisoning more than 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans, roughly two-thirds of whom were born in the United States. They were sent to prison camps, forced to live under armed guards and behind barbed wire. It marked one of the most shameful chapters in American history.

Like other Japanese and Japanese Americans at the time, Vacaville’s Japanese residents were given little notice before they were uprooted and forced to take only what essential belongings they could carry. They were sent to a temporary assembly center in Turlock, then relocated to prison camps at Gila River in Arizona where they would remain until the end of the war in 1945.

Floyd Shimomura grew up on an apricot orchard near Vacaville and remembers spending a great deal of time there as a child. His mother, father, grandmother and grandfather were all incarcerated as part of the executive order.

“Vacaville was one of the earliest agricultural communities. In 1895 it was the third-largest Japanese community in the U.S. after San Francisco and Sacramento,” said Shimomura, who also served as national president of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) from 1982-1984. He worked on redress efforts that ultimately resulted in The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided a formal apology and reparations.

After the war, when the makeshift prisons were shut down, racism kept many Japanese and Japanese Americans from returning home to Vacaville. The Solano County supervisors, the Vacaville Chamber of Commerce and the Vacaville chapter of the American Legion all passed resolutions opposing their return, according to an article in the Times-Herald.

“The Japanese American community there didn’t survive well after World War II,” Shimomura said. “That area, especially after World War II, was very hostile to the Japanese. It wasn’t just general sentiment. They were organized.”

In preparation for the expected return of Vacaville’s Japanese community, Vacaville citizens established the Anti-Japanese League in December of 1944. They gathered signatures on a petition, which more roughly 90 percent of Vacaville’s residents at the time signed, promising not to hire anyone of Japanese ancestry, and not to lease, rent or sell them property, according to written and oral accounts.

“It’s extreme racism, frankly, and fear. It’s a sad, reprehensible history that most people don’t really know about,” DeCaro said. “The positive thing I learned is most people who learn of this history want to make it better for the future. They don’t want to repeat those mistakes. When you get to know your neighbors one-on-one and you get to know your community, that’s what can prevent this from happening again.”

At the Vacaville Museum, the historical photos and impact of the Japanese community requires piecing together various entries and photos; the oral history has never been digitized and remains on cassette tapes.

“It’s kind of a dark spot for Vacaville. The way their entire district was immediately torn down right after internment, I expect they did not expect or want anybody to come back. It played a huge part in why they chose not to return,” said Kaitlyn Moxon, curator at the Vacaville Museum.

One of the last vestiges of Vacaville’s Japanese community can be found at the Vacaville-Elmira Cemetery. Tucked away in a far corner of the cemetery are Japanese graves with markers dating back to the late 1800s. The cemetery includes the San Gai Ban Rei stone marker relocated from where the Buddhist church once stood; it also includes the E Ko Jo Sho stone raised in 1957 in memory of Vacaville’s Japanese residents, according to Omo i de: Vacaville’s Lost Japanese Community, co-authored by former Vacaville resident Takashi Tsujita.

Tsujita’s book sums up what happened in Vacaville this way: “Nearly 60 years after our families were uprooted from Vacaville, scant evidence remains of our life here. Most of what is left can be found on the hillsides of the Vacaville-Elmira Cemetery.”

(About the Author: Jeanne Mariani-Belding is an award-winning former journalist and Pulitzer Prize judge. She is a Stanford University John S. Knight journalism fellow and served as national president of the Asian American Journalists Association.)

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

This article beautifully highlights an important piece of Vacaville’s history that deserves more recognition. The resilience and contributions of the Japanese American community are truly inspiring, and it’s crucial to continue preserving these stories for future generations. Honoring their legacy not only deepens our understanding of local history but also reminds us of the strength found in cultural heritage. Thank you for sharing this insightful piece!