By Janelle Kono, AsAmNews Contributor

When I was younger, I occasionally heard references to a long-lost relative. His name, Masao, was uttered exclusively in the context of his death, which was during combat in World War II. As I gained interest in my Japanese American ancestry, I asked around about him but found my relatives knew very little about the elusive Masao.

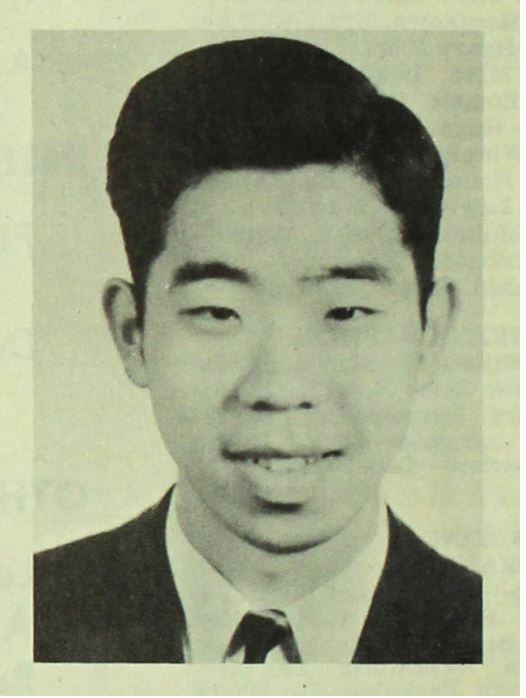

Recently I discovered the full name of what would have been my second cousin: Frank “Masao” Shigemura. I found that not only did he die in combat in the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat in World War II, but his life and subsequent death resulted in a cascade of events that continues to inspire individuals across America.

Frank was born on December 1, 1922 to Takejuro Shigemura and Kay Kono Shigemura. He grew up in Seattle, WA, and where he graduated from Broadway High School and eventually enrolled in the University of Washington majoring in economics and business administration. In February of 1942, in the midst of Frank’s studies, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which resulted in the internment of over 120,000 Japanese Americans including Frank and his family.

Frank and his family ended up in Minidoka, a major concentration camp located in Idaho. This was one of the largest concentration camps used to house Japanese Americans and held a total of 13,000 internees throughout its time as a relocation center. Important infrastructure had not been completed prior to the arrival of the residents. Water pipes broke, sewage could not keep up with the incoming inmates and overflowed resulting in a public health crisis. Construction continued in the midst of the living spaces of residents. Fortunately for Frank, he did not need to stay in these conditions for long.

Frank’s situation of facing an abrupt interruption to his studies was far from unique. In response to the forcible removal of Japanese American individuals from their homes, the National Japanese American Relocation Council was formed with the hopes of removing young adults from internment camps and placing them in colleges where they could finish their degrees. The council acknowledges the skepticism and discrimination these individuals would encounter at these colleges and hoped these individuals would serve as “ambassadors of goodwill” and thereby help improve the landscape of views internees would face in their eventual release from camps.

It is through this program that Frank found himself at Carleton College, a liberal arts college located in Northfield, Minnesota. He was the first student to join Carleton through this program in fall of 1942, but this did not deter him from delving in and making the most of his second chance at college. Frank jumped into campus life by residing in the dorms and joining Carleton’s swim team. Years after his death, his mother noted that Frank referred to his time at Carleton as some of the best times of his life.

One of the most remarkable parts about Frank’s story is that even with the unconstitutional treatment he received having been interned as a potential enemy of the state simply because of his ethnic heritage, Frank remained a staunch patriot. He joined the Army in the Enlisted Reserve at Carleton, and he fully intended on fighting in combat for his country.

In the spring after enrolling at Carleton, Frank reported to officer training along with 60 other members of the Carleton Reserve Corps. He alone got rejected. He was also the only individual of Japanese ancestry. Lindsey Blayney, who was, at the time, the Dean of Carleton, remembers Frank coming to his office in frustration, lamenting, “Why have I been refused? I was born here and love my country as much as my classmates.”

This incident elicited fierce indignation from Blayney. On Frank’s behalf, Blayney wrote a volley of letters to the Army, beseeching them to allow Frank to serve. In one such letter, Blayney wrote, “The sincere efforts being made by this young man to do his part on behalf of his country merits, in my judgment, the earnest consideration of the proper authority. The fact that he is now in the Enlisted Reserve instead of being in a Relocation Center has, as you will see from his letter, worked to his disadvantage rather than the contrary.” At the end, he added, “I quite sympathize with him in finding himself to be only one of the 60 members of the Army Enlisted Reserve at Carleton College not called to service on March 13th. He has made an excellent impression here and, in my judgment, there is no question about his patriotism.”

Just before the end of the school year, Blayney received the order for Frank to report for active duty on June 26th, 1943. After completing basic training, Frank joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated unit made of all “Nissei,” or American-born Japanese men. His unit was sent into northern Italy in June of 1944. After driving the Germans into the mountain ranges of northern Italy, the 442nd embarked on the mission that turned them into the highest decorated unit in terms of their size and length of service in the history of the US military.

In the battle termed “The Lost Battalion,” the 442nd was sent in to rescue a Texas National Guard unit. The Texans were stranded on a mountain range, trapped by approximately 6,000 Nazis in the Vosges Mountains in France. They were not the first unit to attempt a rescue mission. Two battalions tried and failed before them. Yet they were instructed to reach the Texans regardless of the cost. Despite miserable conditions, shells constantly raining down on them, and horrific casualties, the 442nd managed to reach and free the Lost Battalion of Texans through pure tenacity and ferocity. The number of casualties suffered by the 422nd far outnumbered the number of men rescued. 211 of the initial Texan unit were rescued. 216 of the 442nd were killed in combat during the rescue and over 850 were wounded.

Among those killed in this battle was Frank Shigemura. His mom wrote in a letter that Frank, “made his last effort helping his comrades to safety.”

After his death, an unexpected friendship formed between Frank’s parents, and Carleton College. This connection began after Lindsey Blayney, the Dean from Carleton that had advocated for Frank’s ability to serve, sent a letter of his condolences having heard of Frank’s death. Each time the Shigemuras corresponded with the college, they generously included a monetary donation. This money was put into a scholarship in Frank’s name that is still given out to an incoming Carleton student each year.

Carleton fought to ensure that Frank, and the other Carleton students that had lost their lives fighting in World War II, were not forgotten. They published a memorial booklet with the pictures of each young man who lost his life serving in World War II, as well as built a Student Union in their honor. Carleton was not the only college to remember Frank’s life and legacy. The University of Washington, Frank’s initial college, was also impacted by Frank’s death. The University of Washington Nissei Alumni Association built a Universtiy District home since Japanese Americans were not allowed to live on Greek row. This building was named SYNKOA to represent the first letter of the last names of each of the fallen men they recognized. The S, of course, represents Frank. A scholarship in Frank’s name is also awarded at the University of Washington.

In addition to these acknowledgements of Frank’s ultimate sacrifice within the colleges Frank attended, Frank’s story has been widely publicized. The unlikely friendship that formed between Frank’s parents’ and Carleton College around Frank’s legacy was featured in Reader’s Digest in 1950, along with several follow-up pieces. More recently, Fred Hagstrom, a current professor at Carleton College, learned about Frank’s story and hand-produced art books filled with silk-screened photos relating to Frank’s experience in incarceration as well as in the war. The book, Deeply Honored, is featured in special collections across the country. Hagstrom has also given talks across the country shedding light on Frank’s story. Having learned about the Japanese Internment in college, Hagstrom felt it was important that other people learn about this important piece of history. Each talk he gives, he hopes to educate others about this period of time seen through Frank’s story. “There’s going to be someone in the audience who doesn’t know about the Japanese Internment.”

Frank’s death left a strong impact on those he left behind. Most closely affected by his death were his parents. His mom wrote, “It is hard to realize that Frank will never return. I can only say that I am thankful, that he was able to serve his country, God, and us all. I shall always be proud to be the mother of a true American hero.”

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a contribution.

Thanks for sharing the information about your second cousin. His life continues to inspire through your words.

Janelle-we’ll done! I’ve read much of the historical information you cover in your article but have never heard of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council.

Having edited stories about your great uncles serving in Vietnam war, the focus on one individual during WWII is touching and unique. Thank you for sharing this well written historically accurate story. It is the kind of example I’d like to include in the family book we are collecting stories about your great uncles on the Sakura side of your dad’s family. Thank you for sharing.