By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

Ying Ze Wang (王英则) and her husband Jin Sheng Liu (刘金生), leaned against one another on Tuesday underneath a party tent set up in the garden of the Ayudando Latinos a Soñar (ALAS) cultural and social services organization in Half Moon Bay, California.

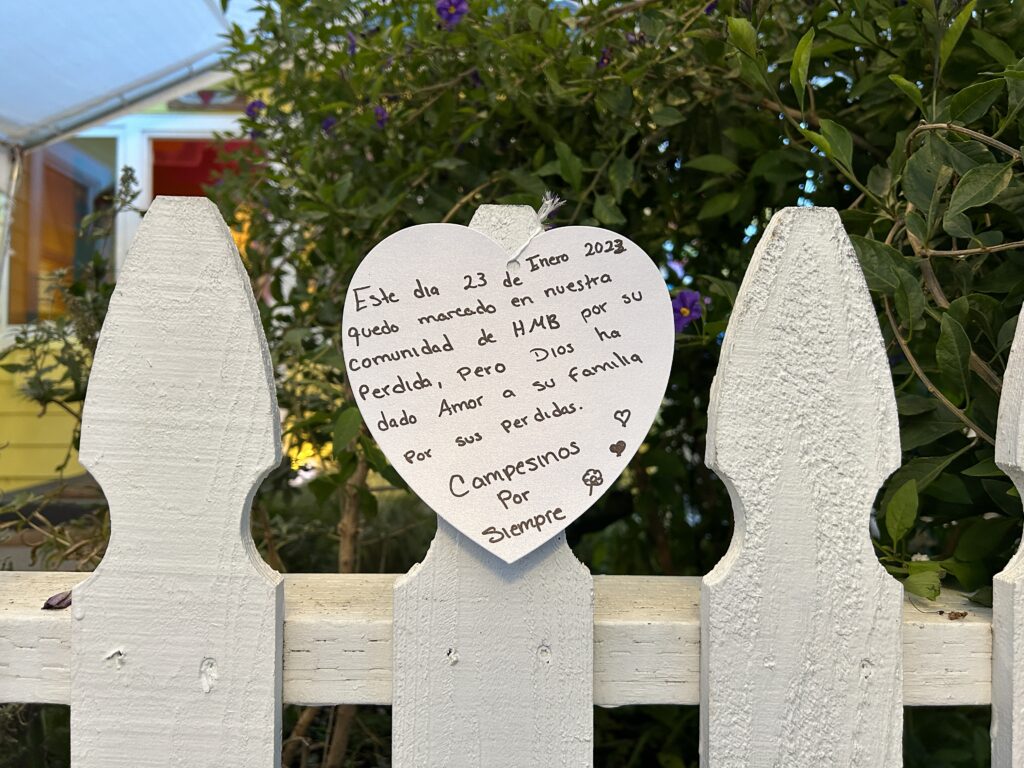

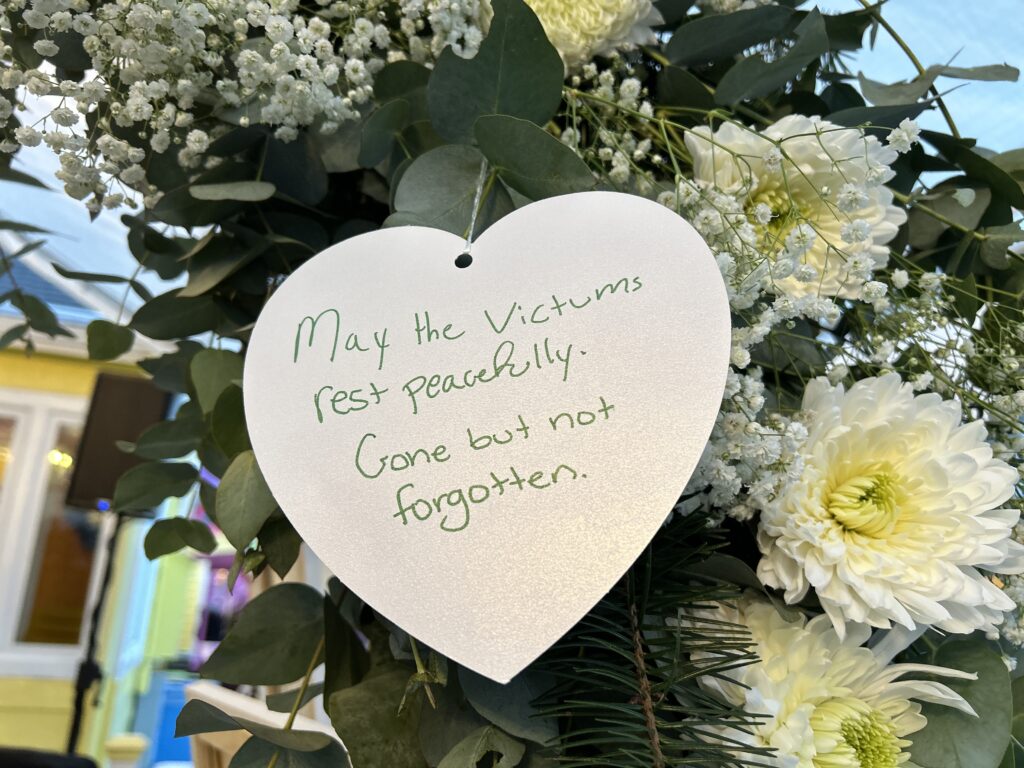

Wearing thick jackets as armor against the wet, cold evening, they watched a mariachi band open up the Corazón del Campesino Memorial Evening honoring five Chinese and two Latino migrant workers shot to death exactly one year prior. The suspect, Chinese national Chunli Zhao, has yet to be arraigned after a delay in the court proceedings Tuesday.

Then 66, Zhao was living at Mountain Mushroom Farm (now California Terra Garden) and working as a forklift driver. He had been in the U.S. for 11 years, had a green card, and legally possessed his semi-automatic handgun.

On the afternoon of Jan. 23, 2023, possibly triggered by a disagreement with former boss Huizhong Li over who would pay $100 in equipment repairs, prosecutors say he gunned down four fellow workers and injured one at California Terra Garden before proceeding to Concord Farms, where Wang and Liu both lived.

The couple heard gunshots and then saw their three bloodied friends on the ground. Liu had worked as a farmer for six years alongside the victims and tried to help them.

“It was terrifying. I was thinking that they were alive. Some of the coworkers called 9-1-1- but they were dead,“ Wang said to AsAmNews at the memorial a year later.

She recalled that one of the victims’ families came by but could not enter the farm. Workers were stuck at the site and waited for hours with the bodies until the farm closed and the gates opened.

Afterward, Wang and Liu became one of 18 families displaced from their farm dwellings. They have not returned to work because of post traumatic stress. The humid conditions at the farm had stiffened Wang’s joints; she used a walker to get to her seat.

After a separate commemoration last Sunday, Liu, still on medication for trauma, couldn’t sleep because of flashbacks. Wang had also started feeling anxious and depressed as the one-year anniversary began to near.

“I wanted to come here to show my remembrance,” she said, explaining why she and her spouse showed up anyway to the memorial.

Sao Leng U, Director of Social Services at the Self-Help for the Elderly, provided Mandarin-to-English interpretation for Wang as she spoke to the respectfully swarming press before the event began.

The San Francisco-based nonprofit, powered by bilingual social workers, advocates, and volunteers, played a crucial role in working with ALAS, emergency assistance groups, local leaders, and other relief entities to deliver basic needs, temporary housing, government funds, cash donations, and mental health care to the Chinese survivors.

She said that the ALAS workers were compassionate, tireless people who had already been supporting both Chinese and Latino farmworkers. When disaster struck, they went out of the way to find Asian community workers who could ensure that Chinese survivors and loved ones of the victims received the same care as everyone else.

According to the 2020 census, Half Moon Bay, a small coastal city in the San Mateo County of California, is 73% White, nearly 25% Latino, a little over 5% Asian, and less than 1% Black. But a common refrain among city officials and the Asian community alike after the mushroom farm shootings was that nobody knew about the Chinese population out in the fields until some of them were killed by another Chinese worker.

U, taken by surprise by the deadliest attack ever to take place in San Mateo County, has remained in close contact with Wang and Liu, along with a younger couple and single person who still work on the farms and fear being identified.

She has also been helping the shooter’s wife cope with the aftermath of the shootings. Before law enforcement found Zhao lying in his car next to his weapon and took him into custody, where he remains without bail, she received a text message saying that he would see her in the next life.

In what District Attorney Stephen Wagstaffe told CNN was a coincidence, Zhao’s hearing took place on the same day, on the one-year anniversary of the shootings. After indictment by a grand jury on Friday, Zhao was arraigned on seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of attempted murder, with the special circumstance allegation of multiple murder.

A continuation requested by Zhao’s public defense attorney Jonathan McDougall will take place in February, when the defendant will be able to enter a plea. If convicted, Zhao could spend life in prison or be sentenced to death, though California governor Gavin Newsom placed a moratorium on capital punishment starting in March 2019.

It was a long day for the Half Moon Bay, which also hosted a discussion called the Half Moon Bay Cross-Sectors Leaders Roundtable: Remembering and Advocating One Year Later at noon at the ALAS Sueño Center on Main Street.

Survivors, farmworkers, dignitaries, officials, residents, reporters, and loved ones filled the white wooden folding chairs, stood around the perimeter of the vibrantly orange-painted room, and crouched on the floor to listen to the speakers.

The event began with the reading of a statement from President Joe Biden and recorded greetings from acting labor secretary Julie Su. Representatives from The White House’s AANHPI initiatives, California governor Gavin Newsom’s offices, and the United Farm Workers appeared in person.

Julián Castro, the Obama-era Housing and Urban Development Secretary and former Democratic candidate of the 2020 presidential elections, attended as new CEO of the Latino Community Foundation.

He sat beside U.S. Congresswoman Rep. Anna G. Eshoo (D-Palo Alto) of California’s 16th Congressional District. Eshoo promised that she had secured “serious funds” for the Half Moon Bay Farm Worker Resource Center and other projects important to the city and its people, pending the President’s signature.

She said, “You know, no local government has the money for everything. We just don’t. It requires a partnership. But let me say something to you. None of these dollars and future dollars would be coming into this community if it was fighting with each other.“

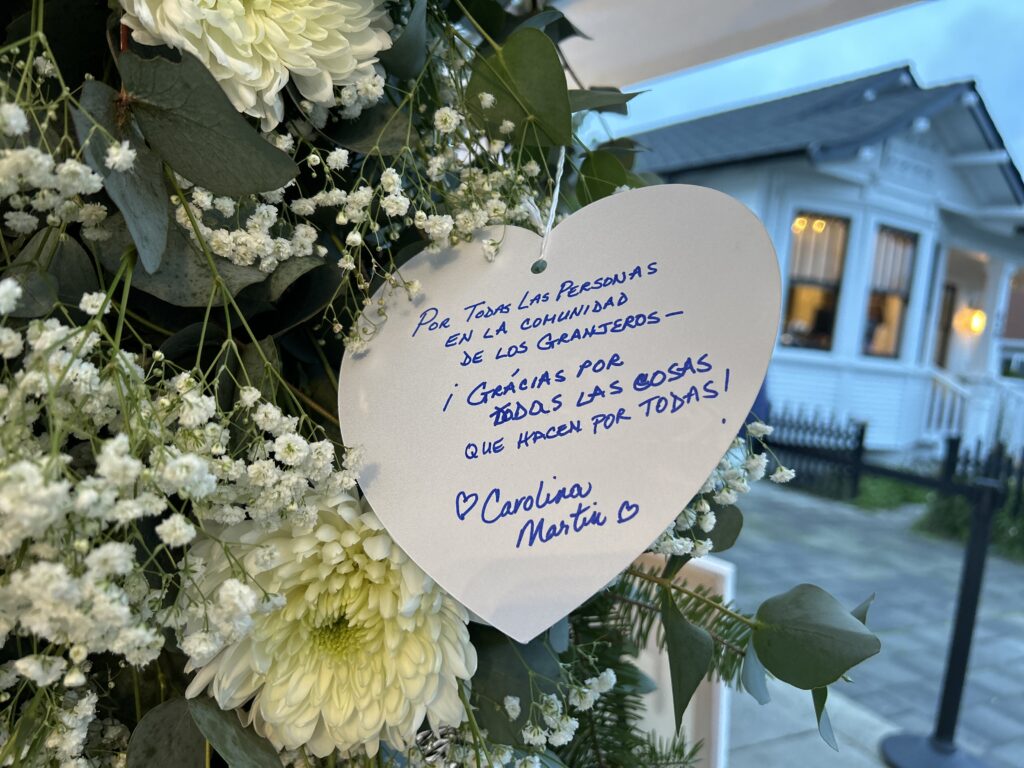

Apropos to this, local leaders and grassroots community workers flexed the loving cooperation that has made the city, county, state, region, country, and world pause to behold the plight of Latino and Asian farmworkers in America in the wake of the shootings.

Half Moon Bay’s first-ever Mexican immigrant mayor Joaquin Jimenez took the floor, with his long braid swinging in an arc behind him.

Also the farmworker program director of ALAS and farmworker outreach and liaison specialist at Puente de la Costa Sur, Jimenez reported that he had engaged with farmworkers all over the country in the past year.

“What we saw in Half Moon Bay is nothing compared to what’s happening in other states,” he said. He shared how most migrant workers in this country are undocumented and live in tents, without a voice.

He concluded, “Change happens here at home. Because when change happens from here, it ripples into other communities. It gives them the hope to speak up. It gives them the hope to … for somebody to step up and amplify their voices. For what? Just the basic needs, with just the basic needs. I’m saying: Half Moon Bay, we are becoming a model community to other communities.”

Jimenez had a message for politicians as elections approach: “Don’t use farmworkers when you’re planning your next move. They are not your pawns. They are the kings and queens are the fields. And we have to respect that.”

Testimonies from family members of the killed followed, showing how fresh their losses remain.

Pedro Romero, the brother of victim Jose Romero Perez who had been critically injured in the shootings, said that he, his father, and his brothers had come to the U.S. from Mexico to have a better life and build a home. They were not able to do this.

“I need your help because now I only have to think about this tragedy that happened. My brother, Jose Romero, was with me and now he’s no longer with me,” he pleaded.

After speeches by a few other community workers, Marisela Martinez-Maya spoke about her “Uncle Martian,” her nickname for Marciano “Martin” Martinez Jimenez, 50. The farmer, who volunteered his free time to a local free clinic in Half Moon Bay, was watering mushrooms when Zhao shot him in front of a coworker.

She attended the burial of her uncle in Oaxaca in her parents’ stead because they could not make the trip. Martinez Jimenez had spent 28 years in the States – saddened relatives back in Mexico hardly knew him anymore.

“I just had a sudden realization that this was not okay. This should not have happened,” Martinez-Maya said, describing her thoughts while walking in a procession accompanying her uncle’s casket from the church to the cemetery. “This was not the way my uncle and I were supposed to go back.”

“I just want to say my part with my experience because that’s something that no one here knew about. No one here knows everything we went through on that day,” she concluded, before thanking all those present for their support.

Her father, Servando Martinez Jimenez, the victim’s brother, followed up with statements in Spanish while the audience sniffled.

None of the Chinese survivors or family members of Chinese victims was there to share their memories or information about how they had laid their beloved to rest.

Dr. Belinda Hernandez-Arriaga, EdD, LCSW, executive director and founder of ALAS, said that the stateside family members of the Chinese victims told her that they still felt unable to speak because of the enormity of their grief. She emphasized the need for the most vulnerable to tell their stories so others can help.

Groups representing the Asian community included and were not limited to Stop AAPI Hate, and the Asian Pacific Fund, and Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA), which had raised and distributed $200,000 directly to the affected families.

Rather than closure, there was a prevailing sense of beginning – the start of a shared resolve to keep the momentum going for Latino-Asian solidarity inadvocating for change on many fronts.

Cynthia Choi, co-executive director of CAA, said, “No one should feel alone. No one should feel because of their immigration status, or their inability to speak English, that they don’t deserve to get support and help…this politically charged environment has made it very fearful for people to seek services. And that’s just the reality.”

She added, “These tragedies bring attention to our communities, it brings a spotlight. But once the media attention once these anniversaries pass, we cannot forget about the ongoing needs of the community. And that is our collective responsibility.”

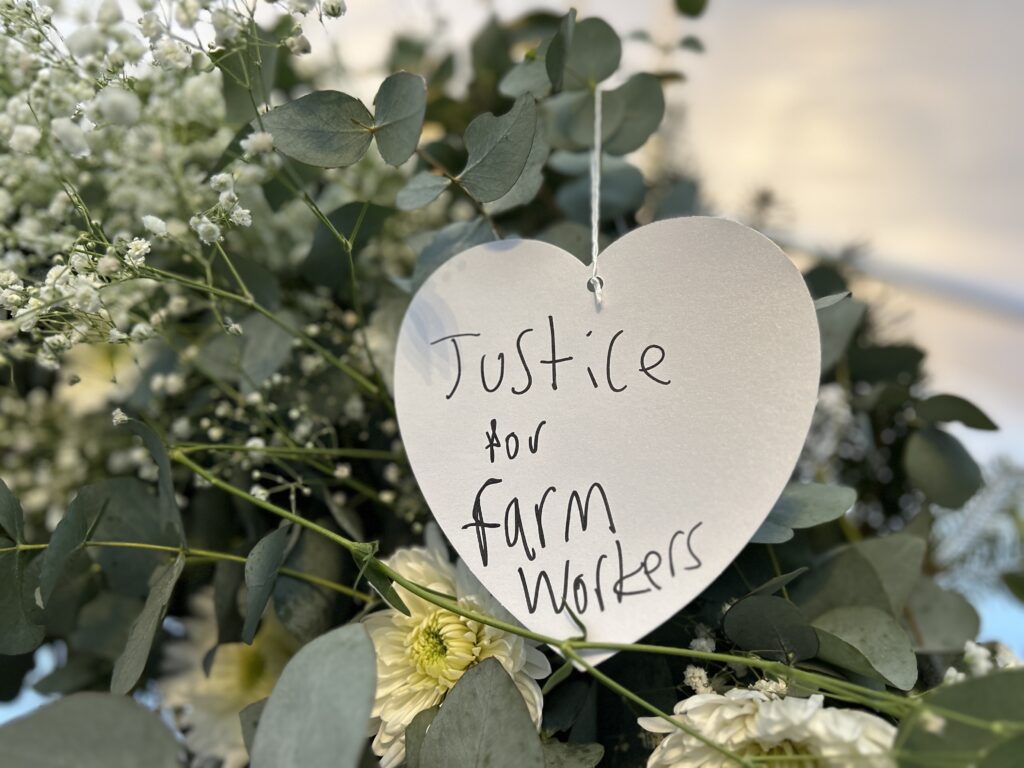

Judith Guerrero, granddaughter and daughter of farmers and the executive director of Coastside Hope, echoed this, saying, “There is one piece that I’ve noticed that it’s always missing. And it’s an immigration reform, because a lot of farm workers are afraid to speak up, thinking that they will lose their job. Whether you believe it or not, there’s still owners of farms that will use that as a measure of fear. So I do hope that there’s a permanent solution coming soon.“

The examination of farmworkers’ rights provoked by the shootings also led to workplace safety and labor justice accountability, the fast tracking of badly needed affordable housing projects, revived demands for clean water, emphasis on language services for non-English speakers, and better data to know who lives where and what they need.

Half Moon Bay’s calls for gun control have also gotten louder. The U.S. has more guns than people at a ratio of 120.5 firearms per 100 people – the highest level of civilian gun ownership by far in the world. Asian gun ownership has increased in response to quadrupling hate crimes against people of Asian and Pacific Islander ethnicity, among other factors. And more incidents of mass shootings are being perpetrated by Asians – a horrific new normal Asians in America are being forced to face.

“I was shocked. I never thought this would be an issue in our community,” U said later at the ALAS casita and garden.

Last but not least was a spotlight on mental health services for the hard-working poor. The Latino and Chinese mushroom farmers were discovered to have worked and lived under stress, fear, and inhumane conditions before they lost their friends, companions, and fellow laborers to a man who said in court that he had not been in his right mind.

“Health screening, mental health screening is really important for all the population because if we cannot reach them when screening is happening, then we cannot provide services,” U informed the crowd.

Eshoo interjected and asked whether the Chinese survivors felt more connected to and confident in the Half Moon Bay community after the outpouring of services, care, and housing that had come their way so far.”

U responded, “They feel nervous. They feel as anxious because now, this is the transitional period. But they can see the hope.”

Antonio D. Lopez, Mayor of East Palo Alto, who had traveled to Oaxaca to pay his respects to Martinez Jimenez last year, closed out the session with a spoken word performance.

As afternoon turned to night, cold rain misted outside the wide-open back door of the ALAS center’s casita. Sitting at a vacated desk in a room glowing with a soft mix of electric and natural light, U waited for one of the organization’s workers to return with single dollar bills to place into red Chinese funeral envelopes embossed with gold Chinese blessings.

When the dollar bills arrived, she stuffed one into each sleeve with a piece of wrapped hard candy. Recipients of the envelopes were to eat the treat and spend the dollar as soon as possible for good luck.

As she worked and answered incessant texts lighting up her phone, U explained how she had ended up here.

“I would say my whole life is a social worker,” she joked.

She was a social worker for 20 years in Hong Kong before she came to the U.S. six years ago to raise her children in a less stressful environment. Her mother was already living here.

She found her way to Self-Help for the Elderly and works in a branch in San Francisco with 64 staff members. Over 400 personnel total span 10 senior centers and healthy meal sites all across the Bay Area.

When ALAS contacted her because there were no Chinese-speaking providers in Half Moon Bay, she knew she had to do something. She had been thinking about the importance of mental health resources for her community, too.

“Asians, we are all silent, ‘I’m good, I’m good,’ until the day you’re not good and you do something crazy,” she muttered.

The City of Half Moon Bay soon contracted Self-Help to provide language interpretation for the Chinese survivors. U went from being floored by the existence of Chinese-speaking farmers to being on the inner circle of migrant workers who remain unidentified to the public. They have divulged that other Chinese migrants not only work at their farms but occupy managerial positions.

As they arrived, U rushed to greet them and help them to a seat. Té de canela cinnamon tea and café de olla spiced coffee perfumed the air as others began sitting down and the vigil began.

After opening remarks and a moment of silence, U and Hernandez-Arriaga read the names of the departed.

U read:

- Zhishen Liu, 73

- Qizhong Cheng, 66

- Yetao Bing, 43. Bing had narrowly escaped a previous incident of gun violence at California Terra Garden when Martin Medina allegedly shot through his manager’s trailer. The bullet went right through the walls and entered Bing’s trailer, where he lived with his wife Ping Yang.

- Aixiang Zhang, 74

- Jingzhi Lu, 64

Hernandez-Arriaga read:

- Jose Romero Perez, 38

- Marciano Martinez Jimenez, 50

After another reading of Biden’s letter, Julián Castro reappeared before the community to express commitment to the Latino community of Half Moon Bay.

San Mateo county supervisor Ray Mueller took the platform next.

He asked for the community’s forgiveness and affirmed the county’s vow for continued transparency about the poor living and working conditions of farmworkers discovered on the night of the shootings and beyond. He said he was sorry for how people had been cooking under tarps in the rain, particularly after heavy flooding that preceded the shootings.

He said that multiple housing projects, including one devoted to the elderly, have been progressing, and that the displaced farming families would be first to move in. He also announced the purchase of two more 50-acre plots for housing.

He ended by saying that the greatest insurance that history will not repeat itself is the community’s voice. He reminded workers about the new Office of Labor Standards Enforcement that takes anonymous calls from workers fearing retaliation by employers.

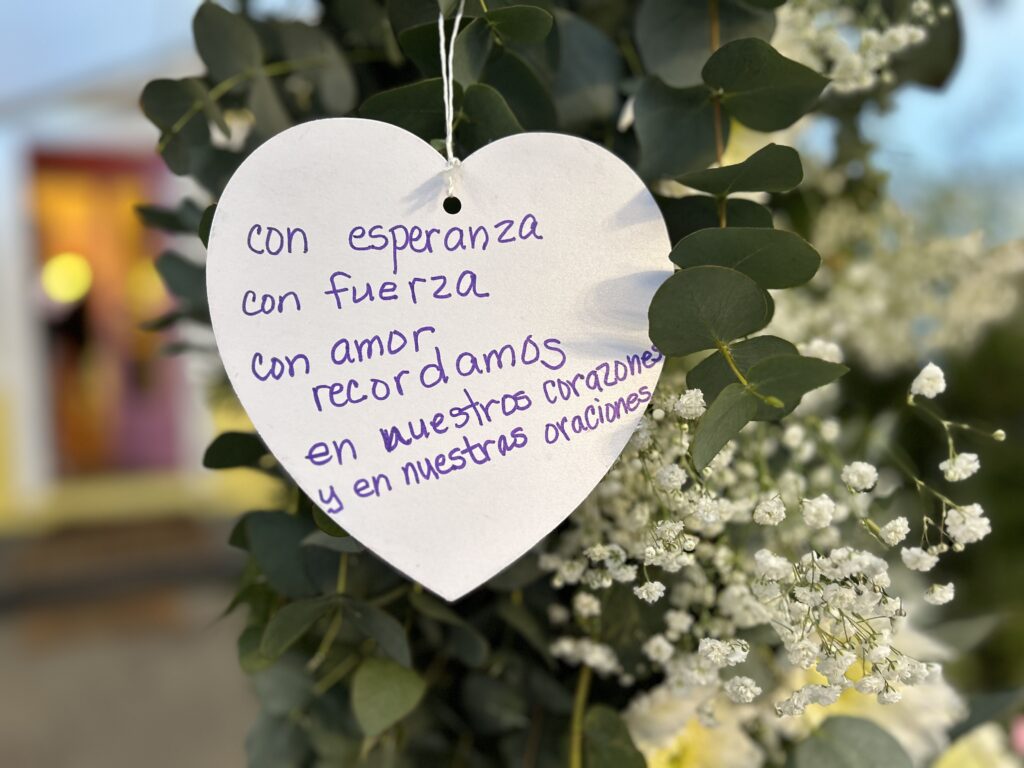

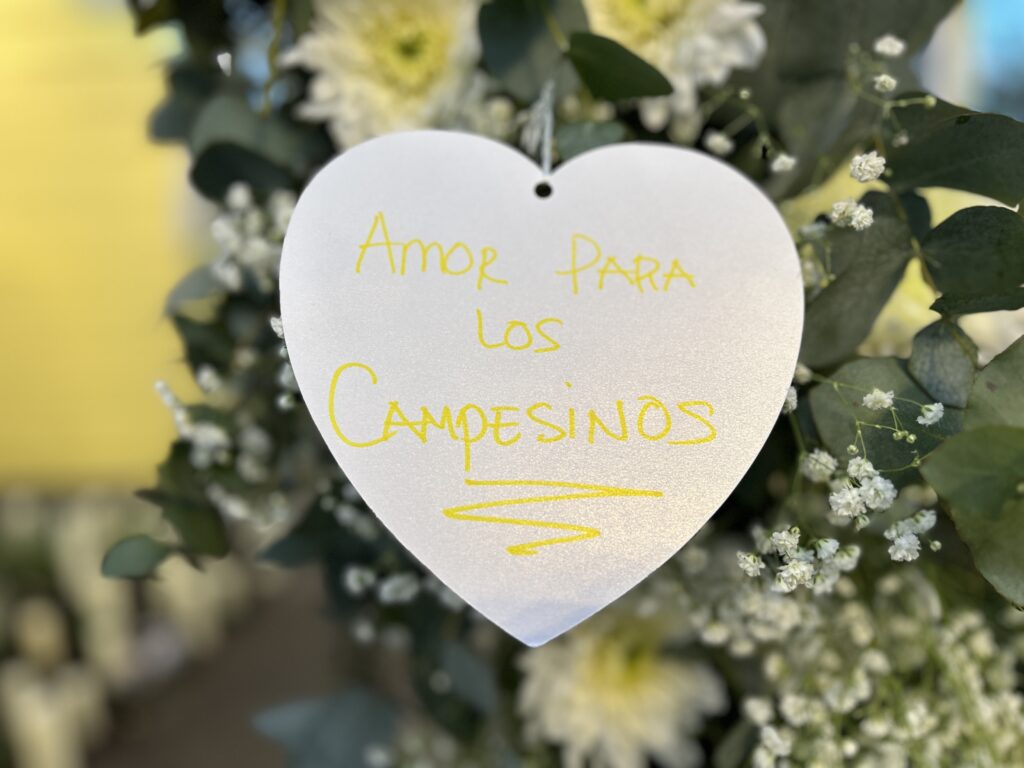

U addressed the farmworkers directly at the evening event. She said, “We want to show our love. You come here because you care, because you are one of the members of this community and the United States. We come here because we don’t want to set a border – ‘oh, you are coming from Latino population, you are coming from Chinese population.’ We are all united and that makes us strong. Hate is no longer here. We want to say thank you to all the victims – they sacrificed their lives but they will always be in my heart.”

Jorge Sánchez and Norma Zavala, case managers for ALAS, shared their remembrances of the Latino and Chinese farmworkers whom they had gotten to know so well before their deaths.

Sánchez, sporting a green ALAS hoodie that boasted “OUR VEGGIES ARE MOON RAISED,” said that language barriers had been a minor obstacle to overcome in order to provide love and share laughter with the Chinese migrants.

“We remember the most beautiful part of them,” he said.

“I could say a thousand words about all the memories,” continued Zavala. “We are always going to remember their smiles, their joys, the difficulties they shared…they are always going to be here.”

Antonio De Loera-Brust, communications director of the United Farm Workers (UFW) union brought things back to the macro level. He quipped, “You can’t pick a tomato over Zoom.” He counted the ways that the pandemic, forest fires, floods, and high temperatures had repeatedly made more Americans acutely aware lately that “this is what people who put food on our table are going through.”

He declared, “Our goal is not just to make the poverty of farmers manageable; our goal is to eliminate poverty for farmers.” Everyone applauded and cheered.

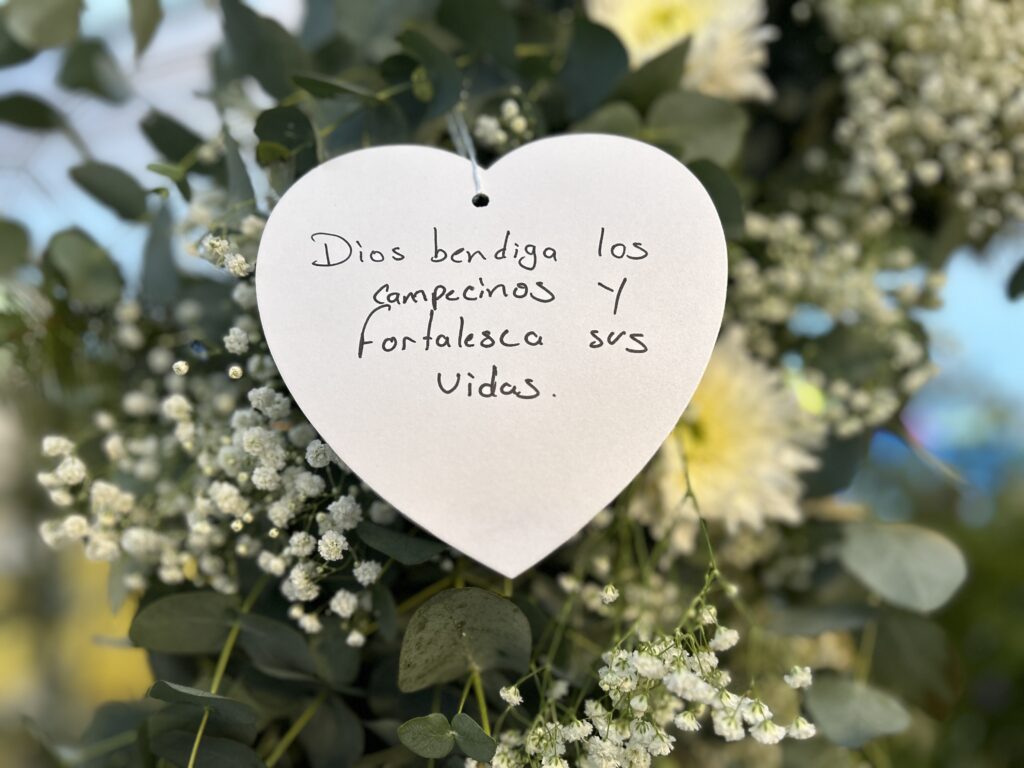

The audience lit each other’s candles, which they had received from volunteers before the event commenced.

A healing program of art and music followed. Hernandez-Arriaga mentioned to the audience how accordion instruction had been helping Pedro Romero cope with the death of his brother.

Then, in a much-awaited moment, sculptor and Redwood City resident Fernando Escartiz unveiled Corazón del Campesino (Farmworker’s Heart), the namesake of the memorial.

Speaking in Spanish with a translator, Escartiz explained that his art piece, a flaming heart with wings and fresh flowers at its center, was an enlarged milagro – Mexican “miracle” religious charm for good luck and protection.

The wings symbolized immigrants who at one part of their lives decided to fly far from their roots, which nevertheless grounded at their origin. The flames represented the fiery passion with which farmers work the earth every day. The heart symbolized the unity and love promoted by ALAS – the elements that unite a community.

He added that the tragedy had hit him all the harder because his partner is Chinese and he has connected with that culture in addition to his own Mexican heritage. He said that the heart stood just as much for the union of the Chinese and Latino communities affected by the shootings.

Finally, he said, “This piece has a part and a section where you can actually put a live flower in it, so that the community maintains the live flower.” He hoped keeping fresh flowers in the sculpture would make sure no one ever forgets the tragedy or the farmworkers who continue to live and work across the country.

“They are the essence of life,” he said.

Jeff Gee, Chinese American mayor of Redwood City, followed up with a short statement that Asians and Latinos had to keep working together the way Filipinos had marched with César Chavez in the 1965 Delano Grape Strike.

He praised the mariachi band and introduced Sandy Li, who played a tribute of a Chinese piece on the guzheng plucked zither, followed by a light reprise of “Amazing Grace.”

As the crowd disbanded and milled about, ALAS workers served up the comfort of buttery pork, chicken, and mild spinach tamales, along with concha confectionary bread and paper cups of warm atol de elote masa-based drink.

Before getting food for herself, Grace Jin, a second year medical student with a curriculum split as a Root Division artist, exchanged numbers with Escartiz in hopes of collaboration.

Dr. Rona Hu, medical director of the Acute Psychiatric Inpatient Unit at Stanford Hospital, had called her in for translation help days after the shootings. Jin, born in the States but raised back and forth between Connecticut and Southern China, had the bilingual language skills that were proving to be painfully rare in a time of emergency.

Jin’s involvement awakened her to her community’s blind spot in regard to its own people.

“It was clear that there was a disconnect between communities that were migrants, that came as migrant workers and railroad workers that built this country. They were forgotten within our own communities and diasporas,” she said.

Working with the survivors led to ponderings about the grief and collective trauma of diasporic Asians who have lost places to talk about and honor ancestors left halfway around the world.

“Forging a space for this is an antidote to that displacement,” she told AsAmNews, in front of Escartiz’s sculpture.

For last year’s Qingming – a “Tomb-Sweeping” festival celebrated in early April in China as well as by ethnic Chinese around the globe, Jin created the Diasporic Tombsweeping art project and event.

The artist displayed traditional Chinese calligraphy on mulberry fiber banners and burned joss paper and spirit money by the Angel of Grief on the Stanford campus.

The installation attracted interactions from people of diverse backgrounds such as Indian and Vietnamese. Together, they shared how they mourn and honor their ancestors and roots.

“It’s kind of isolating here in Half Moon Bay,” she mused, imagining what it would be like to be a Chinese farmworker. She plans on making paintings and installations as altars to the Sino diaspora – a method of “bearing witness and alchemizing memory and history.”

By the time she left to drive back to the Bay Area, stragglers were carrying away the last chairs and picking up stray candle stubs and mini water bottles off the ground.

One of the last people standing was Matthew Chidester, city manager of Half Moon Bay. Between bites of a tamale that steamed into the night, he shared how he had grown up in the city and noticed a slow increase in Asian residents but not the hidden network of Chinese migrant workers.

He said that he hoped and expected that visibility of Asian and Latino farmworkers would only increase from here on out.

“And then we’ll find the next group, probably,” he admitted, staring off into the unknown.

All photos by Jia H. Jung

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. This holiday season, double your impact by making a tax-deductible donation to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews. Less than $5,000 remains in matching grant funds. Donate today to double your impact and bring us closer to our goal of $38,000 by year-end.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.