By Jana Monji, AsAmNews Contributor

The second episode of Asian Americans, A Question of Loyalty, debuted Monday night and while this episode centers on one exceptional Japanese American family, it also looks at how other Asian American families dealt with World War II as well. The title refers to the loyalty questionnaire that divided up the Japanese American community, but also the racism behind it.

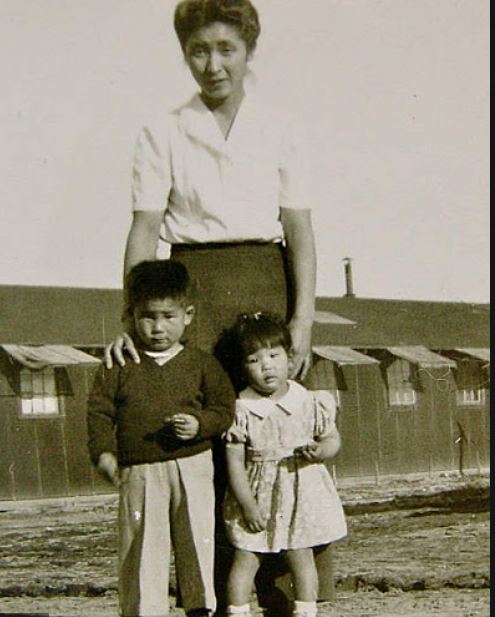

Visually, the documentary makes it very clear that the Japanese Americans were treated like criminals. They were fingerprinted and had mug shots. Even orphaned babies with as little as one-sixteenth Japanese ethnicity were considered a danger to the West Coast. There was one family who was just like a classic Civil War story, as descendant, Roberta Uno described them. George Kumemaro Riki (Kita) Uno’s family was a Christian family with ten children. The eldest son, Buddy, frustrated that his race limited his career options, goes to Japan and becomes a reporter for a mainstream newspaper there. One of his brothers, Ernest, will survive the war fighting in Europe as a member of the 442nd. Two others, Howard and Stanley, will become part of the Military Information Service. Howard would later meet his brother Buddy when Buddy was a US POW. . The youngest brother, Edison, would become a civil rights activist and his sister would outlive him to help complete his work.

For Korean Americans, the US was a safe haven from Japanese imperialism. Ahn Chang Ho (Or Ahn Changho) used the pen name “Dosan” in his anti-Japanese activism. Dosan would be imprisoned and tortured by the Japanese several times, ultimately dying in Busan in 1938. His daughter Susan Ahn Cuddy (1915-2015) was born in Los Angeles and became the first Asian American woman to join the US Navy. Post World War II, she defied anti-miscegenation laws to marry Francis Cuddy and worked on top secret projects. Her eldest brother Philip Ahn (1905-1978) was a pioneering Asian American actor, finding World War II a booming time because actual ethnic Asians were used to play evil Japanese military men.

The documentary also notes that “almost half of the male Filipino population in California” enlisted in the military. Dixon Campos remembers that some older men lied about their age to enlist. The documentary, unfortunately, does not add a bitter twist. The US would “retroactively annull the benefits promised to the veterans and their widows and children.”

In the first episode Breaking Ground, Bhagat Singh Thind who was also a former vet was mentioned, but he was one of several hundred who were denied citizenship supposedly promised for military service. The Nye-Lea Act later granted 500 World War I vets from “barred zones” citizenship in 1935, just a few years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and 17 years after the end of World War I.

Breaking Ground also outlined the racist character of the emerging Hollywood so you won’t be surprised that despite the fantastic Asian American stories seen in the Ahn and Uno families, even now, in 2020, there are no major motion pictures about either.

The question of loyalty is particularly timely as the country re-opens and some people use the word “patriot” to be defined by support for the current president.

Historian Brian Niiya notes that “we tend to frame these things in terms of loyalty: are you for or against us,” but for the Japanese Americans or any US citizen or resident whose family immigrated to the US, the issue isn’t that simple. “There are no good answers in a lot of cases.”

Roberta Uno states that going to the country of one’s ancestors can bring up a “feeling of no longer being a marginalized person, a minority” and for her, “a way of defining my loyalty is by speaking up.”

For some Asian Americans, that means speaking up about the South Texas Family Residential Center–the largest immigrant detention center in the US. That Dilley, TX facility opened in 2014 and is about a 40-mile drive the Crystal City internment camp where two Unos were until 1947, two years after the war ended.

One point that has become more timely with COVID-19 and the rise of anti-Asian hate incidents, is the efforts the Chinese and Korean Americans made to indicate they weren’t Japanese. While there are t-shirts available on websites like Redbubble to insure that people don’t mistake one as Chinese, there seems to be a greater rise of Asian American unity this time around.

Here are some notable people you’ll meet in episode 2:

Japanese American

Satsuki Ina was born in the Tule Lake Segregation Center. She has a private psychotherapy practice in the San Francisco Bay Area, but she is also an activist, writer and filmmaker. Ina was the producer of the 1999 documentary Children of the Camps and the writer, producer and co-director of the 2005 From a Silk Cocoon. Both films are about the Japanese American internment camps. From a Silk Cocoon won a Northern California area Emmy Award.

Edison Uno (1929-1976) was a Nisei civil rights activist. Born in Los Angeles, he initiated the JACL redress resolution which called for compensation. He also campaigned for the pardon of Iva Toguri (D’Aquino) who had been convicted of treason as “Tokyo Rose.”

Kazumaro “Buddy” Uno (1913-1954) was born in Oakland. He began writing a column for the Rafu Shimpo and was a member of the San Francisco Japanese American Citizens League. As an adult, he began working for the Press Bureau of the Japanese Army as a journalist in Shanghai in 1940. The same year, he was briefly conscripted into the Japanese Army and lost his US citizenship as a result.

Korean American

Ahn Chang Ho has an official website where he is described as an educator, social activist and “a central figure in the Korean Independence Movement.” His five children are pictured and his grandson manages (Cuddy’s son, Flip Cuddy, who is a biomedical researcher) manages the Facebook page.

Philip Ahn (1905-1978) might be best known for his role as Master Kan in the TV series Kung Fu. Locally, he helped make Los Angeles a sister city to Pusan and bring the Korean Bell of Friendship to San Pedro, CA. Philip opened Moongate with his sister Soorah. He was the first Korean American actor to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Susan Ahn Cuddy (1915-2015) also has her own website. The website provides both her and her husband’s bio. Eventually, Cuddy returned to the Los Angeles area and there’s more information about the family restaurant, Moongate, mentioned in the episode. Cuddy’s motto: “Be a good American citizen, but don’t forget your heritage.”

Notable People

Jane Hong is an assistant professor of history at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Hong just published her first book, Opening the Gates to Asia: A Transpacific History of How America Repealed Asian Exclusion (University of North Carolina Press, 2019). The book is about the transnational movement to repeal America’s Asian exclusion laws in the context of black civil rights struggles at home and U.S. military intervention in decolonizing Asia.

Carl Mydans (1907-2004) Was a Life Magazine reporter who in 1944 took the famous “I shall return” photo of General Douglas MacArthur striding ashore in the Philippines in 1945.

Brian Niiya is the content editor for Densho Encyclopedia. He was formerly a curator at the Japanese American National Museum.

Laws

was issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942 and authorized the evacuation of people who were deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast. While this series deals only with the Japanese nationals (who couldn’t become naturalized) and the Japanese Americans (who were citizens by birth thanks to United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)) but to a lesser degree some Italian and German Americans were also interned.

Anti-Miscegenation Laws

California was the first state to repeal its anti-miscegenation law since Ohio did in 1887 (White people banned from marrying Blacks). In California the law applied to Blacks, Asians and Filipinos. Roldan v. Los Angeles County in 1933 allowed the marriage of a Filipino American man, Salvador Roldan, and a White British woman, Marjorie Rogers. By 1933, the California State Legislature amended the law to include “members of the Malay race.” This law will become more important in Episode 4, Generation Rise, because it explains why the Filipino men were single. The California Supreme Court case of Perez v. Sharp dealt with a Latina wanting to marry a black man. At the time, Latinos were considered White. Perez v. Sharp ended anti-miscegenation laws in California in 1948 and was cited as a precedent for Loving v. Virginia by Chief Justice Earl Warren who had been the Governor of California (1943-1953).

RELATED:

Episode 1: Breaking Ground

Episode 3: Good Americans

Episode 4: Generation Rising

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.