By Emil Guillermo

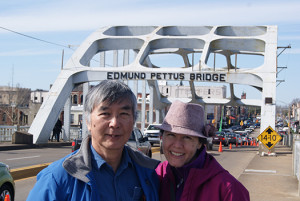

Photos by Vincent Wu

At face value, Vincent Wu, 73 years young this week, looks like many successfully retired Asian American engineers. At Atari, the company that brought the world “Pong,” Wu led the effort to bring “Donkey Kong” home–to the home PC, that is.

Remember the floppy disk version? That was Vincent.

But ask him about the real highlight of his life, and he’ll point to his soul and to Selma.

Fifty years ago, you might say Wu helped bring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. home.

Wu was a volunteer marshal in the historic final march from Selma to Montgomery, where he walked alongside Dr. King as a member of his security team.

At 5-feet 9-and-a-half inches and 155 pounds, Wu said he wore a blue chambray work shirt and jeans, no uniform and definitely not a suit. Only a blue armband made out of plastic, like that of an air mattress, distinguished him as a member of the volunteer perimeter security team. They were never more than 10 or 20 feet away from Dr. King on the march to the Alabama capitol.

“We were jubilant because this was a triumphant event,” Wu told me about the voting rights march. “We were finally reaching our objective, our goal. It was an honor to assist him, to protect him.”

Did King ever speak to him? Wu only laughed. “I’m just a foot soldier,” he said of his days volunteering in the historic march. Wu was a 23-year old in grad school at Illinois in 1965. Like other Americans, he was outraged by the scenes on the TV news from “Bloody Sunday.”

“We answered the call of Dr. Martin Luther King to come down to Selma to bear witness and to stand with the people who were oppressed,” Wu said. “My motivation was for my love of American ideals. It was a moral as much as a political stand for me. I believe in the value of non-violence and respect for every human being. So it stems from a sense of morality and ethics. . .as a human being. . .I was there not as an Asian American student but predominantly as an American citizen.”

Wu was a minister’s son born in the Yunnan province, China, but his family made its way to Hong Kong. At the time, the immigration quotas prevented many Chinese from coming to America. But as a minister, Wu’s father was given special passage to the U.S. to serve at the First Chinese Presbyterian Church in New York City.

In 1951, Wu was just 9 and attended P.S. 59.

“We lived in a mostly white neighborhood, one of only two Chinese families in the school,” he said.

When I said it sounded like Fresh off the Boat, he laughed. As an immigrant with an accent, he could probably relate to both American-born Eddie Huang and his parents.

From midtown Manhattan, Wu moved to San Francisco, right on the edge of Chinatown, and his education resume was typical for many Bay Area Asian Americans: Francisco Junior High, Washington High, San Jose State. But then came Illinois for grad school, and Selma for activism.

He was one of seven in a VW bus, organized by a Unitarian Church. In nine hours, he was in Selma, the start of what would be two weeks that would change his life.

He didn’t see any other Asian Americans. But he did have a sense of danger.

“We were kind of scared,” he said, reminded of the images of the Selma police and Bloody Sunday. “When we drove through, we did not dally

downtown because it was a dangerous place.”

They went straight for the black neighborhoods where they were welcomed, put up in people’s residences in public housing, fed, and treated well.

It was a lot more hospitable than the Montgomery County jail.

You can read the rest of Wu’s fascinating story on Emil Guillermo’s blog in AALDEF.