By Raymond Douglas Chong, AsAmNews Staff Writer

On Valentine’s Day in 1965, at Los Angeles International Airport, a 73 years-old man, with his son, tearfully welcomed a frail elderly woman. After 43 years of estrangement, Moi Chung, my grandpa, finally reunified with Cun Cheun Wong, my grandma, at the terminal gate. They renewed their long-lost love. Gim Suey Chong, my pa, quietly rejoiced.

In 1923, Moi Chung anxiously departed from our peasant village at Hoyping county in Sze Yup region of Kwangtung province of China for Gum Saan – Gold Mountain, aboard a steamer toward Boston. He sadly left a young mother, my grandma with a toddler, my pa.

Five generations of my Zhang forefathers were bitter victims of America’s Chinese exclusionary immigration laws. The U.S. cruelly restricted Chinese immigration, denied citizenship by naturalization, and separated families. Moi Chung was a false student. Gim Suey Chong was a paper son, an illegal immigrant.

My family’s hardship was typical for immigrants of color who faced America’s discriminatory immigration laws before 1965. Minority advocates lobbied Congress for decades to reform immigration without success.

The civil rights movement by African Americans was an impetus for Congress to decisively reform American immigration laws. It was their long struggle for civil rights to raise the awareness and conscience to the power structure that America was not a just and equitable society as envisioned by our Founding Fathers. During the early 1960s, a confluence of civil rights movement events finally compelled Congress to enact civil rights legislation to mend the racial injustices.

Exclusionary Immigration

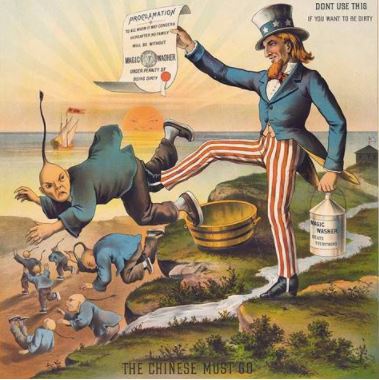

The dreamy myth of a nation of immigrants was a false illusion for America. White American feared the Yellow Peril of Eastern Asians and the Hindu Invasion of Southern Asians, strangers from a different shore. Before 1965, the quota system for race and national origin allowed eighty four percent of American immigrants from Northwest Europe.

Since 1789, United States Congress enacted a series of immigration acts to restrict immigration by non-Whites by racial exclusion to maintain a society dominated by Whites of Northwestern European descent.

- 1790 – Naturalization Act allowed eligibility for citizenship by naturalization to free White persons.

- 1875 – Page Act prohibited the recruitment to the United States of unfree laborers and women for “immoral purposes” but was enforced primarily against Chinese prostitutes.

- 1880 – Angell Treaty with Kingdom of China allowed the United States to restrict the migration of certain categories of Chinese workers.

- 1882 – Chinese Exclusion Act law targeted Chinese immigrants for restriction which severely limited legal entry and ineligibility for citizenship.

- 1892 – Geary Act renewed the Chinese exclusion laws and required Chinese to prove their lawful presence in the United States by carrying a certificate of identity or be detained and deported.

- 1904 – Extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in perpetuity.

- 1907 – A negotiated agreement between President Theodore Roosevelt and Empire of Japan that limited the immigration of its own citizens

- 1917 – Barred Zone Act created a barred zone extending from the Middle East to Southeast Asia from which no persons were allowed to enter the United States.

- 1924 – Johnson-Reed Act established extended national origins quotas.

- 1934 – Tydings-McDuffie Act imposed immigration restrictions on Filipinos.

- 1943 – Magnuson Act repealed of Chinese Exclusion laws but with annual quota of 105 Chinese.

- 1945 – War Brides Act enacted exceptions to the national origins quotas to help World War II soldiers and veterans bring back foreign spouses and fiancés.

- 1946 – Luce-Celler Act extended naturalization rights and immigration annual quotas to 100 Filipinos and 100 Indians.

- 1952 – McCarran-Walter Act provided quotas for all nations and ended racial restrictions on citizenship.

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a long struggle for social justice by African Americans to gain equal rights under the public laws in the United States. It was a valiant war against institutional racial discrimination.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in case of Brown versus Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

For the next nine years, the civil rights movement actively exploded in a series of events. They included the murder of Emmett Till in Mississippi; the defiance of Rosa Park which inspired the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama; the integration of Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas; tje sit-ins at segregated businesses and public facilities across the South; the Freedom Rides in the Deep South; and the integration of Mississippi universities. By 1963, hundred of cities were rocked by peaceful protests and the violent police response.

After the integration of University of Alabama, on June 11, 1963, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy addressed the nation with his famous civil rights speech. He asked Congress to pass civil rights legislation and asked American citizens to embrace civil rights.

I hope that every American, regardless of where he lives, will stop, and examine his conscience about this and other related incidents. This nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds. It was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.

Today, we are committed to a worldwide struggle to promote and protect the rights of all who wish to be free. … It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color.

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities; whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.

President Kennedy proposed immigration legislation for Congress to phase out the national origins quota system, end the Asia-Pacific Triangle (annual quota of 100 visas per country), and institute new entry criteria based on an immigrant’s career path and family status.

On August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in front of the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, his earnest call to end to racism.

After the assassination of President Kennedy, President Lyndon Baines Johnson influenced Congress to act on Kennedy’s civil rights legislation, as well as immigration reform.

Gabriel Jack Chin, immigration law professor at University of California at Davis said:

I think every sensible person in 1965 knew that the sources of immigration would change, … The more fundamental change, and the more fundamental policy, was the articulation by many legislators that it simply did not matter from where an immigrant came; each person would be evaluated as an individual. That kind of argument was novel, but consistent with the anti-racism of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Immigration and Nationality Act

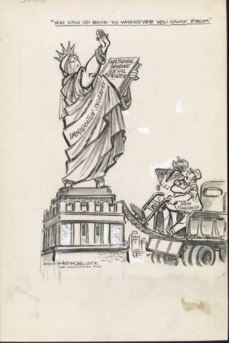

Five decades and five years ago, on October 3, 1965, at Liberty Island in front of the colossal Statue of Liberty in New York City, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as Hart-Celler Act. The public law abolished the national origins quota system that was biased for Northwest Europeans and directly excluded immigration of Eastern and Southern Asians to America. In 1965, the Asian American population in the United States was one million.

This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power. Yet it is still one of the most important acts of this Congress and of this administration. … This bill says simply that from this day forth those wishing to immigrate to America shall be admitted on the basis of their skills and their close relationship to those already here.

— President Lyndon Baines Johnson

Amid the crowd at the signing ceremony was United States Senator Daniel Ken Inouye (D-HI), a World War II hero, along with Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA).

Passage of immigration reform will implement more fully the ideals of equality and justice on which this democracy was founded. … And it will bring truth to the statement that we are indeed a nation of immigrants.

– Senator Daniel Ken Inouye

In his 2003 Becoming American: The Chinese Experience documentary, an epic immigration saga of the Chinese in America, Bill Moyers, a White House press secretary during the Johnson administration, poignantly recalled that signing.

What is striking is how little I remember of that day. So much was afoot in the White House, so many bills were getting signed, that this was almost routine. On October 3, 1965, at about 1:30 pm, we headed to New York’s Liberty Island.

My job as press secretary was just to make sure reporters and camera crews had a clear view of LBJ as he signed a new immigration act into law. Actually we did not consider it such a big story.

I remember as we left, the President put his arm around me, leaned over so no one could hear, and said, “Bill, if this was not a revolutionary law, what the blank did we go all the way to New York to sign it for?”

It turns out, he need not have worried.

None of us knew it at the time, or even intended it, but that bill would take racial bias out of our immigration laws. America had always thought of itself as white – despite its large black minority. Now this would become a country of all shades and tints and hues. The law helped change the country’s identity, the idea of what it means to be American.

And another people would emerge from the shadows; their story would take its place in the making of America.

Years later we could see: the immigration law was a turning point – no – the turning point. Once this last legal obstacle was dismantled, the Chinese were free to come into their own.

The Immigration & National Act of 1965 opened America to more diverse races, beyond White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP) . The Hart-Celler Act set the main principles for immigration regulation. It allowed new categories of immigrants: family members of American citizens; skilled laborers and professionals; and political refugees. The Act greatly changed the fabric of America.

Legacy

Along with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ranks as major achievement during the civil rights movement. It was a catalyst for Asians to freely immigrate to America that led to tremendous growth at its urban centers. Now, United States population of Asian Americans stands at 23 million, versus 1 million in 1965. Congress finally included Asians in America.

The 1965 immigration and nationality act eliminated the national origin provisions of previous acts. Race and ethnicity would no longer be a criterion for immigration and citizenship. President Lyndon Johnson at the signing ceremony beneath the Statue of Liberty stated that previous provisions based on race were un-American in the highest sense. The 1965 act opened large scale immigration to Chinese finally addressing the reunification of families long separated because of Chinese exclusion laws and began the formation of new families among a people who had been largely forced into bachelor Chinatown societies.

– Ted Gong, Executive Director, 1882 Foundation

The former United States Angel Island Immigration Station was constructed to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and similar national policies that sought to impede immigration from most Asian and Pacific Island countries. While the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, it was not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that the US permitted a more diverse mix of countries to finally enter the country in larger numbers. The new Angel Island Immigration Museum will serve as an important reminder not only of our nation’s complex history of exclusionary immigration policy, but also of the important accomplishments and contributions that immigrants have made to the United States.

– Edward Tepporn, Executive Director, Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation

We are living in the world directly shaped and made better by Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 . Without it, we would not see the Chinese American community we have today. We as a community suffered most from the past immigration bill, that is, Chinese Exclusion Act; and we today benefit most from the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. What a chance and what a turnaround! America with diversity is America with dynamics!

– Shue Haipei, President, United Chinese Americans

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was our turning point in immigration for all Asians in America. We passionately believe in American values, while we truly pursue our American dreams. We will overcome racial discrimination with our national unity. America has been built by immigrants who believe in the idea that all men are born equal and free. Our democracy is an experiment trying to achieve that idea. The Asian Americans, just like all immigrants before us, have and will continue to contribute to making America a better country for all to achieve those American dreams.

– C. C. Yin, Founder, Asian Pacific Islander American Public Affairs Association

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was a momentous immigration reform in America. Since 1965, the public law radically transformed the racial diversity of the nation. Asians, including my Zhang family from China, are now included in a multicultural America. Asian Americans are deeply indebted to the civil rights movement by African Americans for their struggles and sacrifices.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story.

Although the article lists very important milestones in the history of civil rights, I was disappointed not to see reference to early achievements of Chinese American civil rights organizations in the late 19th century. Appealing anti-Chinese rulings up to the U.S. Supreme Court, they established milestone judicial precedents of racial “due process” (Yick Wo-v-Hopkins 1886) and birthright citizenship (US-v-Wong Kim Ark 1898). – Buck Gee, board president/Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation