By Thomas Lee

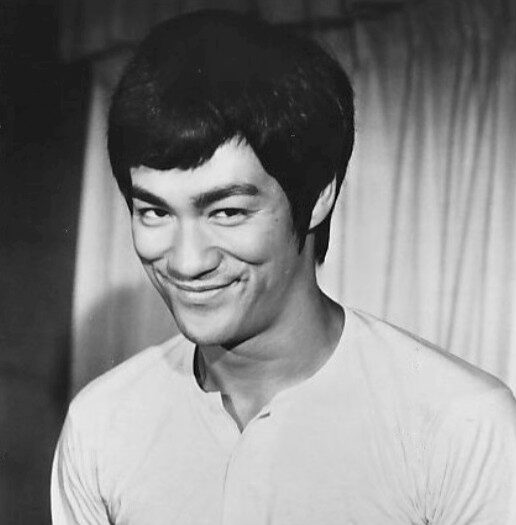

As we mark the 50th anniversary of his death on July 20, 1973, the circumstances of Bruce Lee’s sudden death in Hong Kong continue to attract breathless speculation.

For the record, the official cause of death was brain swelling, prompted by an allergic reaction to some medicine. But conspiracy theories abound, since Lee paid enormous — some might even say obsessive — attention to his health. A recent study even suggested that Lee drank too much water, which caused his brain to swell.

But I wish the conversation would shift from how Lee died to how he would have lived had he woken up from the nap he took on that fateful summer afternoon. What would he be doing today? What would he be saying?

Lee’s global fame and infamous death have unfortunately distorted what really made the martial arts legend so special. Despite spending much of his life in Hong Kong and speaking with a pronounced accent, Lee was as American as they come, both legally and spiritually.

He was born in San Francisco in 1940, which automatically made him an American citizen. But even as a young man, Lee immediately grasped the can-do entrepreneurial spirit that has long defined this country’s image of itself.

“Fortune, in the sense of wealth, is the reward of the man who can think of something that hasn’t been thought of before,” Lee wrote to a friend. “In every industry, in every profession, ideas are what America is looking for. Ideas have made America what she is, a done good idea will make a man what he wants to be.”

In reality, Lee was not interested in wealth and fame. He didn’t even want to pursue a film career. But Hollywood offered the best and most effective way to realize his ultimate goal: connect East and West by spreading his love of kung fu martial art to the masses.

“I like to let the world know about the greatness of this Chinese art,” Lee wrote. “I enjoy teaching and helping people; I like to have a well-to-do home for my family; I like to originate something; and the last but yet one of the most important is because gung fu is part of myself.”

Lee was truly a child of two worlds and wanted to see those worlds connect. In that way, he predicted China’s decision in 1979 to establish formal diplomatic relations with the United States, a consequential move that brought closer two countries with polar opposite economic systems and political ideologies.

Over the decades, both countries benefited from the relationship as China grew into an economic powerhouse, mostly by cheaply manufacturing goods for Western companies. Cultural exchanges naturally followed, with China even opening dozens of language and culture centers throughout the United States called Confucius Institutes.

Unfortunately, the relationship between China and United States today is at an all-time low, beset by mutual suspicion, economic rivalry and possible military confrontation.

Under President Xi Jiping, China has adopted a highly nationalistic policy that sees a declining America as trying to contain China’s rightful emergence into a dominant global power. Indeed, the fate of Taiwan could lead to a disastrous war.

On the other side, the United States has once again embraced its worst xenophobic instincts, blaming China for Covid-19 and accusing seemingly benign Chinese companies like Shein and TikTok of espionage. Such rhetoric, of course, has led to bigotry and even violence against Americans of Chinese descent, especially during the pandemic.

Lee would be absolutely devastated at what he sees today. He dedicated his short life to bringing the East and West together. I can only imagine that Lee would feel torn between the nation of his ancestors and culture and the country that he loved for its energy and opportunity.

The question is what Lee would do, if anything, about it. He wasn’t overtly political or active in social causes, even though he came of age during the Civil Rights Movement and opposition to the Vietnam War in the 1960s and early 1970s.

In truth, Lee seemed more interested in developing his career. Despite his global fame today, his resume was rather thin: a role in the television series The Green Hornet, which was canceled after one season, and five films that opened in Hong Kong, one of which, Game of Death, was released years after this death.

It’s likely that Lee wanted to feel more secure in his professional and financial persons before participating in politics and social issues.

Asian Americans were (and, despite some improvement, currently are) virtually non-existent in white-dominated Hollywood. Studios could have easily blackballed him the way they ex-communicated directors, writers and actors suspected of Communist ties during the Red Scare of the 1950s.

Ultimately, Lee would have stepped onto that soapbox if he was alive today. He just had too much to say to not say anything. He always saw the big picture and earnestly believed he had a mission to do great things with his life.

I believe Lee would be harshly critical of China. For one thing, he spent little if any time on the mainland. He grew up and extensively worked in Hong Kong, which was under British control at the time.

It was only under those relatively free conditions that Lee was able to pursue his career and generate wealth and fame. As an artist, he had the freedom to fully express himself and spread his deeply humanistic beliefs of fulfilling one’s potential. That individualistic philosophy, represented through Jeet Kune Do, seems incompatible with China’s focus on loyalty to the Communist Party and what its leaders view as the greater good.

When Great Britain handed back Hong Kong to China in 1997, the latter had promised to preserve much of the city’s autonomy under its “one country, two systems” policy. But under Xi, China has cracked down on Hong Kong’s freedoms in recent years, crushing dissent and punishing critics.

Had China done something similar to Hong Kong in the late 1960s and 1970s, when Lee was alive, I very much doubt he would have become the martial arts legend that he is today.

Thomas Lee is a longtime business journalist who currently writes for The Boston Globe. His recent book, The Bruce Lee Code: How the Dragon Mastered Business, Confidence, and Success, was recently named a finalist in the International Book Awards’s Best Motivational Business Book category. He also served as lead curator and editorial director for the We Are Bruce Lee museum exhibit in San Francisco Chinatown.