By Raymond Douglas Chong

The Project

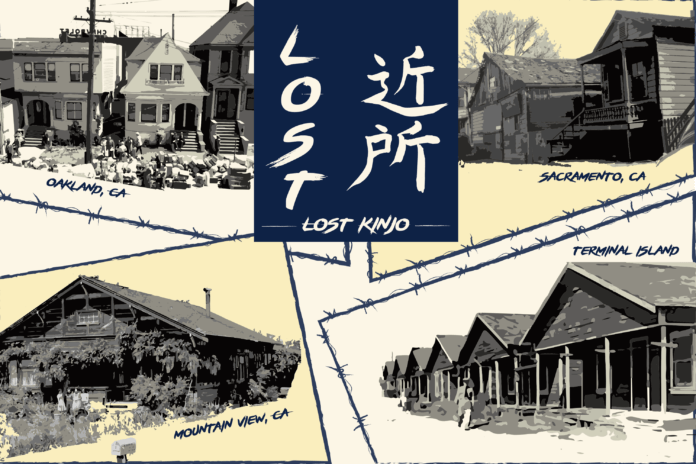

The California State Library’s Civil Liberties Public Education Program awarded a grant to AsAmNews for its Lost Kinjo (Lost Neighborhoods) project.

The incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II resulted in the loss of civil liberties and the disappearance of some 40 Japanese American kinjo (neighborhoods) in California. Through a series of videos, online articles, and first-hand accounts, Asian American Media Inc. will introduce its readers to some of these lost communities, the long-term impact of their disappearance, and why those that survived remain threatened. The articles will also examine the parallels between the kinjo and what is happening today in the Black, Hispanic, Native American, and other Asian American communities.

Diaspora from Japan

In their diaspora, the Japanese pioneers (Issei) immigrated to California, mainly via the Port of San Francisco. They were a new Asian labor force that grew after the enactment of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which restricted Chinese labor. The Issei built the railroads, logged timbers, caught and canned fish and abalone, and raised crops on farms, vineyards, and orchards.

Japantowns (Nihonmachis) formed in cities and towns across California to serve the surrounding communities. The Japanese managed hotels, restaurants, laundries, healthcare facilities, grocery stores, nurseries and other establishments. The business catered to Japanese cultural needs: boarding houses, restaurants, barbershops, bathhouses, gambling houses, and pool halls.

At community halls, they held Japanese celebrations and Japantown festivals. Japantowns usually had Japanese language schools for the Issei children (Nisei), Japanese language newspapers, Buddhist temples, Christian churches, and Japanese hospitals.

The 1940 census shows 93,717 Japanese people living in California before the Pearl Harbor Attack.

Systemic Racism

The Japanese pioneers and their descendants encountered systemic racism of White supremacy. During the transition from cheap laborers to wealthy business and farm owners, they faced blatant Anti-Japanese sentiment under the scourge of Yellow Peril and Xenophobia.

Federal laws discriminated against the Japanese:

- The Nationality Act of 1790: Congress limited those eligible for citizenship by naturalization to “free White persons.”

- Gentlemen’s Agreement: In 1907, the Japanese and American governments concluded the “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” in which Japan agreed to limit emigration to the United States.

- Ozawa v United States: In 1922, in Takao Ozawa v. United States, the United States Supreme Court ruled to definitively prohibit Japanese from becoming naturalized citizens based on race.

- Immigration Act of 1924: Congress imposed severe restrictions on all immigration from non-European countries, which effectively ended Japanese immigration.

California State and municipal laws further discriminated against the Japanese:

- Miscegenation laws: In 1880 and 1905, the Legislature amended Sections 69 and 60 to add “Mongolians” to the list of persons Whites could not marry to extend miscegenation against Japanese.

- School segregation: In 1906, the San Francisco School Board adopted a policy segregating Japanese schoolchildren into Oriental schools to keep them from White schoolchildren.

- California Alien Land Law of 1913: The California Alien Land Law of 1913 was specifically created to prevent land ownership among Japanese citizens residing in California.

- State Political Code: State legislature amended the State Political Code in 1921, allowing separate schools for children of Indian, Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage.

Japanese could not buy homes in specific neighborhoods. They were barred from choice jobs in industries. Many unions prohibited them from membership.

Incarceration

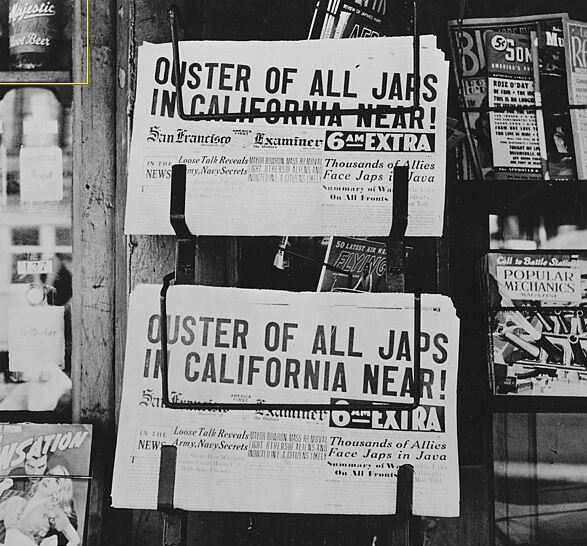

After the Pearl Harbor Attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) enforced an exclusion zone along the coasts of California. Oregon and Washington against Japanese Americans. They forcibly relocated and incarcerated 125,284 people of Japanese descent.

The WRA incarcerated them in ten fenced and guarded “relocation centers” at remote and desolate locales. The relocation centers included Tule Lake and Manzanar, California; Poston, Arizona; Minidoka, Idaho; Topaz, Utah; Heart Mountain, Wyoming; Granada, Colorado; and Rohwer and Jerome, Arkansas.

They endured three years of misery under desolate and primitive conditions in the barren deserts of the American West.

The Disappearance of the Japantowns

After the World War II incarceration, the WRA released the Japanese released into American society. It discouraged their return to the West Coast.

But many Japanese Americans returned to their Japantowns. They endured racial prejudice and hatred by White Americans. They were denied jobs. They had difficulty finding housing. Their neighbors were unfriendly and distant.

The Japantowns in California significantly declined (Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose) or disappeared (more than 40).

Preserving California’s Japantowns

Preserving California’s Japantowns (2008) by Jill Shiraki and Donna Graves documents historical resources from the numerous pre-World War II Japantowns. They developed this list of more than 40 communities to include representation across the state’s many regions and ensure that distinctive economic characteristics and cultural features associated with diverse Japantowns were represented.

Lost Kinjo

In our Lost Kinjo or Lost Neighborhoods project. AsAmNews will examine the loss of these more than 40 Japanese American communities after World War II.

We will look at where members of those communities dispersed, why they left, and how the disappearance of these neighborhoods affected their culture and livelihoods. We will also compare what happened after World War II to communities in danger of being lost today from the Asian American, African American, Latino, Latino, and Native American communities.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.