By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

Occupational therapist Kelly Toy, OTD, OTR/L teared up in the audience as she watched Every Day After at the Silicon Valley Asian Pacific FilmFest (SVAPFF) in October.

She thought of her own life as she watched the 35-minute documentary, which follows a 13-year-old boy named Jary in the Masbate province of the central Philippines before, during, and after his surgery for cleft lip and palate (CLP).

Toy was born in with a bilateral cleft. She is one of the people that the world’s largest cleft-focused nonprofit Smile Train says is born every three minutes with the condition, in which the lip and both hard and soft parts of the roof of the mouth do not close fully during fetal development.

Research has correlated CLP with genetic, environmental, and nutritional factors but there is still no certainty about what causes the condition that makes eating, breathing, hearing, and speaking difficult and requires a lifetime of restorative surgery for those who manage to access and afford it. The facial differences of cleft affected children also expose them to alienation, taunting, bullying, and even abandonment by families and caretakers.

After opening scenes, Every Day After transitions into an animation about how Jary’s parents rejected him at birth before cutting back to the present day.

Jary lives with his older sister Jessa, who sticks by him and cares for him in addition to her own husband and child. The family dwells in a shack with a leaky tin roof on a muddy hillside that is treacherous for worn rubber slippers scrambling under monsoon rains.

Though Jary is shy and nearly silent throughout his everyday existence, he expresses himself at night by dancing alone or with trusted family to hard-driving techno beats in a dirt floor area behind his home.

One day, he gets the surgery he needs to close the cleft in his palate and upper lip. But as the title of the film suggests, his road to physical and emotional healing has only just begun.

When Toy was growing up in the Bay Area, one other child her grade had lip scars – a boy with a unilateral cleft who was very kind to her. People associated the two with one another, which helped prevent either one of them from being singled out.

Still, she once struggled to make eye contact with others – just like Jary, who is seen in the film often looking down at the ground instead of at people or the camera. Facing people directly used to only remind Toy of her biggest difference and insecurity.

“What hurt the most, being cleft affected, was going out in public and the stares I would get from everyone. Babies, children, teenagers and adults would all intensely stare at me and it definitely made me feel ‘other’ and self-conscious,” she said, in a written interview with AsAmNews.

Toy preferred the questions of “What happened to your lip?” and “Why do you look like that?” in comparison to stares. Questions showed a degree of willingness to learn. But sometimes, the questions got old, too.

Fortunately, she had a strong group of friends who were ready to stand up for her. Once, they told classmates, “Hey stop asking her questions, she’s tired of it.”

And she considers herself extremely lucky to have mostly avoided bullying. In fact, people usually held her up as a “good” student to emulate. At school, teachers asked her to stick by peers who needed additional social support.

“At the time I didn’t understand why I was being asked, but as an adult, I get it,” she said.

Toy loved Every Day After. Not only did she relate to Jary, she felt the love and care of her own family and friends radiating through the actions of Jessa. The documentary also made visible what she knew about CLP.

Toy began researching CLP in high school for a biology paper. One of the first things she discovered was that CLP affects Asian people more than any other ethnic group. She found this interesting because most people she knew with CLP were not Asian.

She was dismayed that the solution to CLP for a lot of cultures seemed to be to abandon or hide cleft affected children. She also encountered Asian folklore attempting to give moral and superstitious explanations for why CLP occurs.

“Some Asian cultures thought the mother had a great sin and passed it on to their children. Other Asian cultures believed a mother looked at a rabbit and passed the ‘harelip’ on,” she said.

To Toy, the documentary was evidence that the ignoring or abandoning of cleft affected children continues today all around the world.

“It’s sad, especially because in more rural and remote locations, this has been happening for decades and maybe even more. Most parents that are in underserved populations don’t know how to handle a child with special needs or don’t have the bandwidth or resources to get the help they need, which is why Every Day After is so important,” Toy said.

From banishment into the spotlight

Toy, who was volunteering for the SVAPFF for her sixth time, spoke out about some of her experiences after the film played. So did her mother, Cindy Toy, who happens to be chair of the festival.

And in the post-screening fireside chat with NBC Bay Area news anchor Janelle Wang, executive producer Dave Liu revealed that he himself is cleft affected and only started talking about it three years ago.

As an advisor, author, entrepreneur, investor, filmmaker, and philanthropist with a combined 30 years of experience raising billions of dollars on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley, Liu got into film production through his avid support of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders in all sectors of society. [Full Disclosure: Dave Liu is on the AsAmNews Board of Directors and is a major donor to the outlet.]

Through his philanthropic activities, Liu became a supporter of Smile Train long before he was “out” about his own CLP.

Notably, the organization was founded with a global mindset by naturalized Chinese American billionaire, businessman, and philanthropist Charles B. Wang, who passed away in 2018. Wang was determined to establish local healthcare for cleft affected children instead of depending on Western doctors to fly out to other regions.

A little over two years ago, Liu rose as chairman of the Smile Train’s philanthropic advisory council. When he heard about a film project based on a boy named Jary who was being treated at a hospital in the Philippines supported by the organization, he raised his hand to help however he could.

Liu worked with Emmy award-winning director and producer Elisa Gambino, who envisioned the film, veteran global health and international community cinematographer and editor Neal Broffman, Philippine-based producer Elaine Jose Bobadilla, and the One Production Place Films studio in Atlanta, Georgia owned by Gambino and Broffman.

After the SVAPFF screening, he confided to his interviewer that he used to be full of anger in his youth from the rejection brought on by being facially different from CLP and surgical scars. He said that it was the love of his mother that had kept him from “spiraling into some downward black hole.”

He also used the fury to build up his emotional armor and determination.

“I really channeled all that energy into trying to be the best that I could be, and a little bit of trying to show other people I’m not some freak – I’m not someone who’s going to end up in some dungeon somewhere,” he told Wang.

Once hoping for more public awareness, now vying for Oscars attention

Every Day After became eligible from the point of its world premiere at the HollyShorts Film Festival in Los Angeles in August because it won Best Documentary Short Film. Winning an Oscar-qualified event meant the film entered the database of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

If the doc even reaches the shortlist of 15 titles from which the Academy will choose its five nominations for Best Short Documentary Oscar, cleft affected people around the world could be on their way to receiving more pop culture visibility and understanding than ever before.

Liu is eager to use the film not just to increase awareness of the medical response demanded by CLP but to call out how the entertainment industry unfairly depicts facially different people or those with scars on their faces.

Lists of famous cleft affected people include actor Leonardo DiCaprio, football player Peyton Manning, Reverend Jesse Jackson, and musicians Cher and Florence Welch among other rich, famous, and influential figures. But these examples usually highlight people who managed to blend into the mainstream undetected.

People with more prominent facial differences have long been prey to society’s mocking or typecasting, such as by using makeup and prosthetics to put facial differences on actors playing villains or pariahs.

Liu gave an example of the first episode of the hit Apple TV series Pachinko, in which Hoonie, the father of protagonist Sunja, appears with a cleft. The Korean actor playing the role, Lee Dae-Ho, has no cleft in real life even if the original character in Min Jin Lee’s novel does.

“Kind of like Yellow Face or Black Face for White people – very triggering for cleft people,” Liu texted to AsAmNews.

Liu thinks that any woman, person of color, or anyone else outraged about stereotypes or distasteful depictions of them in media and entertainment are natural candidates to advocate for the fair representation of facially different people as well.

He hangs onto rare positive examples of CLP representation, like Passages (2023), starring cleft affected European actor Franz Rogowski in his first major English language performance, and M. Knight Shyamalan’s Knock At The Cabin featuring 9-year-old Kristen Cui as Wen, a cleft affected Chinese adoptee.

Cui is not cleft affected and there have been some criticisms from the cleft affected community about the role she played. But CLP is a matter of substance in the movie, not a visual insinuation of certain character traits.

Liu set out hoping that Every Day After would contribute toward ending negative tropes for facially different people once and for all. Initially, the plan was to circulate in as many festivals as possible. After HollyShorts, the team shifted toward making sure to get considered seriously for Oscar nomination.

For the past past month and a half, the film crew has been focused on getting the attention of any of the hundreds of mysterious members of the Academy worldwide. There are about 100 qualifiers already in the Academy’s portal; many will never be seen once by the members.

“If we win the Oscar that’s worth a thousand of these festivals in terms of exposure, right? Not even winning, I mean, just getting to the shortlist,” Liu said.

Every Day After teamed up with short film Nisei and short documentary Between Earth and Sky to host “For Your Consideration” screeners giving Academy members the chance to see three Oscar-qualified films in one sitting.

Since its debut, the film has also appeared in Albuquerque, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Cannes, Amsterdam, and the San Jose International Short Film Festival, where it also won Best Documentary Short.

The film’s last showing of this calendar year was another For Your Consideration event on Dec. 5 at the Lincoln Center in New York City, on the tails of a Nov. 29 screening at the Crescent Theater in Los Angeles.

Now, it’s time to wait and see what the Academy decides.

The face behind the man: Dave Liu’s story

Smile Train cites the global rates of CLP incidence as 1 out of 1,200 for Black people, 1 out of 700 for White people, 1 out of 500 for Asian people – highest of all.

As common as CLP is for his ethnic demographic, Liu grew up feeling totally isolated.

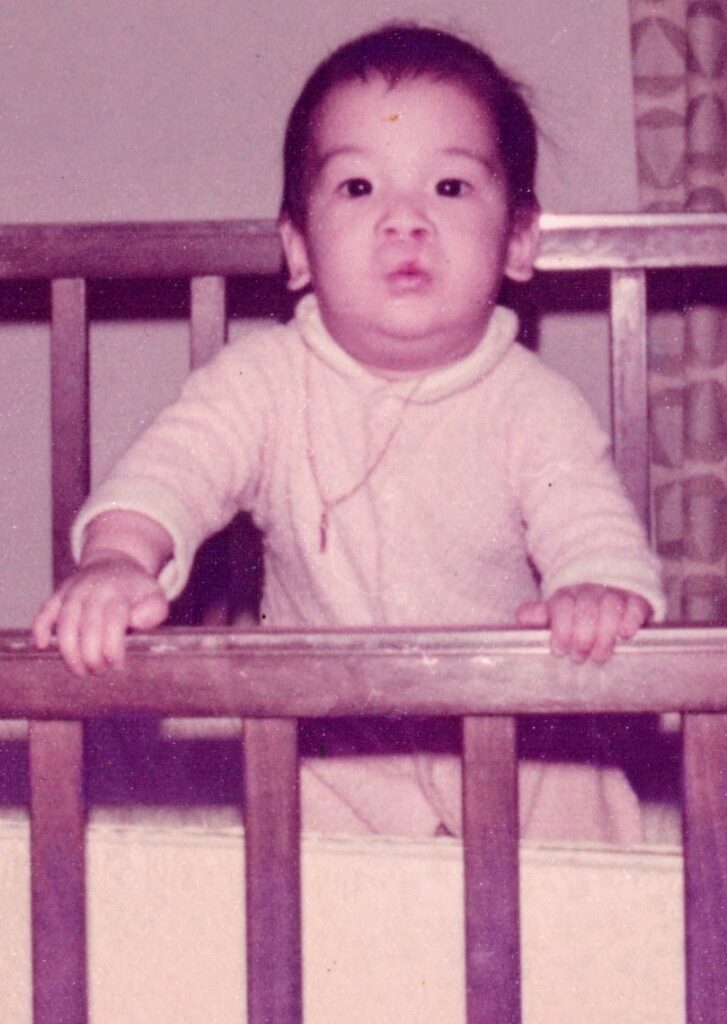

He was born in Houston, Texas to a Chinese father from Hong Kong and a Filipino mother. When he was two, his father brought the family back to Hong Kong to pursue his business.

Liu was the only cleft affected child in their community there. Other children teased him constantly, calling him “Elephant Boy” and “Monster.” The overt attacks stopped by high school, but the stares did not.

In a conversation with AsAmNews, he likened being the recipient of the constant stares to what a woman might feel from the worst possible version of the male gaze.

“It’s like, people look at you like, you’re a frickin’ freak, right? And you feel it at your core. Like, wherever you look, people are staring at you,” Liu said. Even the teachers did it.

During this period, he made only one friend, with whom he remains close today. The largely unverbalized care and normalcy with which his mother and brother regarded him were his life buoys.

At 15, Liu returned to the States for education, unfazed by being one of the only Asian people in the room in addition to being the only cleft affected person in the room.

“I was like, okay, yeah, I’m a minority here. But who cares? I’ve lived my life as a minority of one,” he said.

At the same time, he had instant, built-in empathy for the challenges faced by Asian Americans and felt uniquely suited to understand and advocate for the community.

At 16, Liu entered the University of Pennsylvania as a mathematics major in the liberal arts school. When his father cut him off financially after a downturn in business, Liu transferred into a track to earn dual engineering and Wharton business degrees. He got a job at Goldman Sachs at age 19, the summer before graduation. After finishing a five-year program in four, he went straight to Wall Street.

Facially different people representing facially different people

To break through the “bamboo ceiling” of limitations Liu saw for Asian professionals in the realm of finance, he consciously transformed his introverted self to into an all-out extrovert.

The change was gradual. He bought a suit to accentuate his six-foot-tall frame. In his thirties, he grew a beard. When everyone stared at him in the boardroom, he made sure to say something smart, useful, and memorable until he had a seat at every table and rose steadily up the corporate ladder.

Years later, he was writing The Way of the Wall Street Warrior: Conquer the Corporate Game Using Tips, Tricks, and Smartcuts, selected as one of Bloomberg’s best books on business and leadership in 2021.

He began talking about life as a cleft affected person because he had to do so in order to explain how he had become tenacious, developed a thick skin, seized opportunities without waiting for anyone’s permission, and leveraged unwanted attention.

The advice, originally meant for his two sons, also offered insider’s information to help women, people of color, and anyone else used to being that lone person in the room achieve advancement.

As a young adult, Toy went on to earn a doctorate degree in occupational therapy. Last December, prior to graduation, she published her capstone paper and an accompanying poster about the role of occupational therapy in CLP treatment.

She also submitted the work to the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (APCA) that sets guidelines for CLP surgical procedures but was turned away. She might try again but wonders whether the scientific community thinks CLP is such a common topic that it fails to leave room for the study of individual experiences living with the condition.

“We’re just a statistic, so it’s hard for people to relate and be empathetic and understanding,” she said. “I think films like Every Day After is great because it gives context and humanizes the person with CLP.”

Toy believes that this representation is especially important for kids who are cleft affected.

Ethnically Chinese herself, she said, “I think for being cleft affected, I find myself drawn to Asian people that are cleft affected more often than not, but we all go through similar experiences.”

Early in her life, her parents showed her a film about a Chinese girl with CLP. ”It made me feel seen,” she said. Later, she was part of a Discord group, a few Facebook pages, and Operation Smile’s community. But Discord’s members were mostly European, Facebook served mostly parents of cleft affected children and Operation Smile had a younger crowd that she felt she aged out of after college. She was just as happy with her pre-existing group of friends.

While searching for participants for her post doctoral research, though, she met an 18-year-old cleft affected girl from Bhutan on Facebook. The girl reminded Toy of herself but had not yet undergone palate repair surgery. As a result, she was extremely self-conscious about how she sounded and worried about her employment prospects. She still practices speaking daily; Toy stays in touch with her as far as their schedules allow.

She connected with Liu before and after seeing Every Day After and intends to remain in contact with him, too, as she continues learning more about CLP and finding others who live with it.

“Every Day After is really just a small snippet of what happens in someone’s life that is cleft affected,” she said. “Everyone will experience their cleft differently, and no matter how you experience it, it’s all valid.”

Not one and done

“Smile Train is leveraging the film to raise awareness about clefts and the need for all cleft-affected individuals to have access to effective, safe and timely comprehensive cleft care,” the organization wrote to AsAmNews.

Smile Train, the Every Day After film team, and Liu also want people to know the story does not end there.

“We want to just educate people that it’s not just one surgery, or even two surgeries, it can be a lifetime of surgery. Like for myself, it’s been 13 craniofacial surgeries, and hopefully I only have one or maybe two more. And I’m 51, so it’s been literally half a century of surgeries,” Dave told AsAmNews in a video chat just weeks after his latest operation.

Before Liu began speaking out about his CLP, only his closest circles knew about all the medical procedures he underwent.

“I had to break my face twice a day,” he recalled, of a previous surgery that drove him consume opioids to manage his pain.

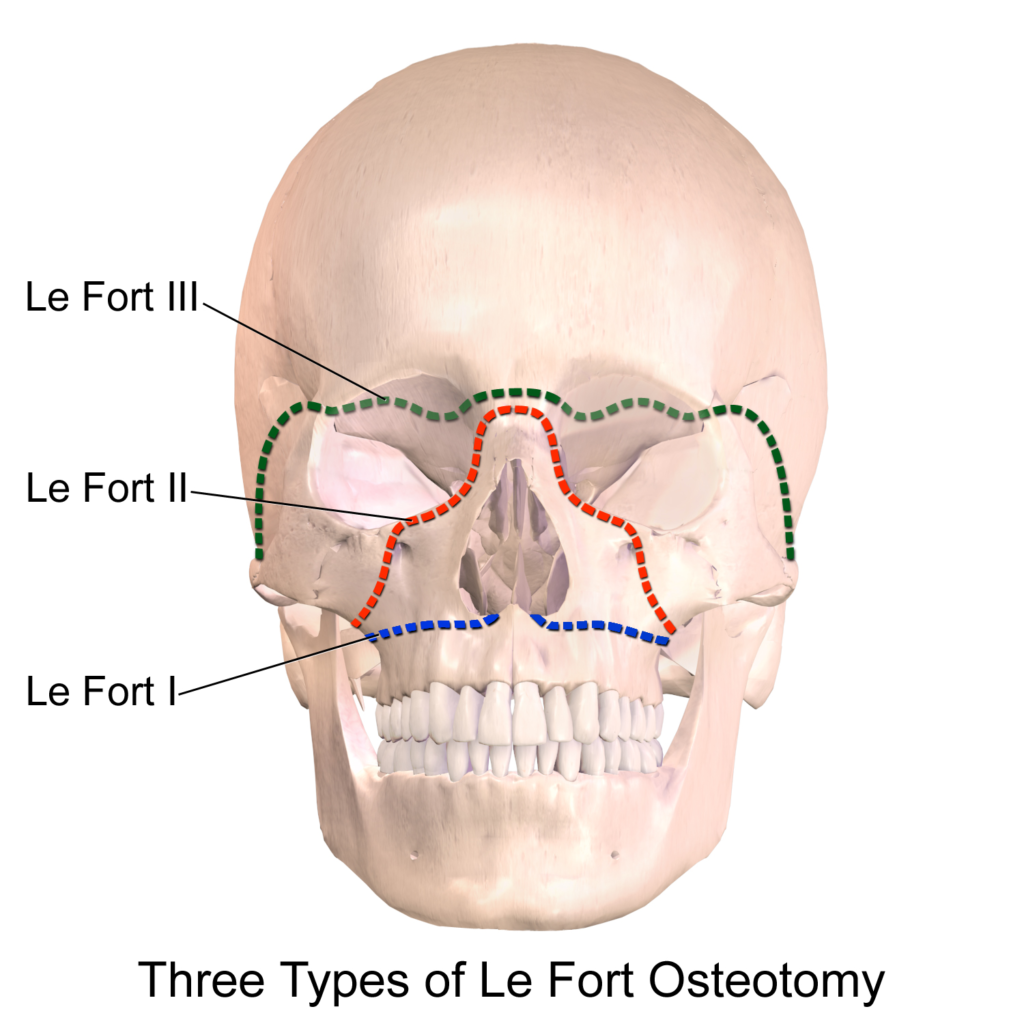

He described the Le Fort osteotomy adjusting his jawbones as “medieval” – the procedure involves sawing open the face to leave tiny gaps so that blood and cells can flow into it, generating new bone.

For months afterward, a Le Fort osteotomy patient must periodically turn a little crank to keep cracking healed bones apart again to create more growth.

Liu’s wife helps him turn the crank.

This time, the doctors inserted titanium plates into Liu’s face – these will be permanent unless infection calls for extraction.

Liu’s face always feels numb after surgeries like this. Half the feeling comes back after six weeks. Then, he starts to feel random zaps like electric shocks across his face as severed nerves regenerate and find new pathways.

Offline in an email, Toy told AsAmNews that she has had more than five surgeries so far.

Memories from the early ones blend together. She remembers vomiting after waking up from surgery because of the blood she ingested. Drinking her lunch out of a thermos. Hobbling around after a surgery that removed bone from her hip to graft onto her palate.

She holds onto the kindness of a volunteer named Matt, who found her in the surgical prep area when she was a little girl to give her a brown stuffed bear with a red ribbon and a sticker that said “courtesy of the volunteers.”

Ahead of her most recent surgery for her jaw and nose about ten years ago, she had the foresight to ask the team to pump the ingested blood out of her stomach this time before she woke. And after discharge a couple of days later, she texted friends through the night when facial swelling made it difficult to sleep.

Like Liu, she had hardware to twist twice a day, three to four revolutions each time.

She did it herself – it hurt.

The neverending quest to heal

Now 29, Toy continues her work as a pediatric occupational therapist at an outpatient clinic, collaborating with other occupational therapists, as well as physical therapists, feeding therapists, and speech language pathologists.

She helps children with special needs play, dress, eat, go to school, and do anything else important to their “occupation” of being a kid. She helps her young clients fasten buttons, pull zippers up and down, and put on shirts, pants, shoes, and socks. She also teaches emotional and sensory regulation strategies to help improve their attention and independence.

“I haven’t come across anyone that’s cleft affected yet, but I’m hoping to one day,” she said.

She wants to eventually get into occupational therapy and feeding in relation to people with CLP. In the meantime, she is exploring background on how CLP and mental health affect social participation and engagement in desired activities. She wants to learn as much as she can before going deeper into advocacy, preferably for groups that help cleft affected people explore interests and activities that they might not normally feel comfortable pursuing.

As for Liu, he said, “I strongly believe in the power to film to change people’s minds. As such, I will continue to show our film and use it as a conversation starter to change people’s perceptions of cleft and facially different people.”

While prioritizing the Oscars until the Academy’s announcements expected the end of this month, the Every Day After team is also seeking distribution opportunities, especially in classrooms full of young, impressionable students.

People interested in learning more can go to www.EveryDayAfterFilm.com to sign up for a mailing list for news, future screening alerts, and ways to support the film and cleft affected people who need care and recognition.

Next March, Liu will be part of a panel entitled “Changing Faces: Media Representation and the Path to Positive Portrayals of Facial Differences” at the South by Southwest (SXSW) conference in Austin, Texas.

And he wants to do more, so much more, not only for the cleft affected, facially different, or Asian communities.

Beyond films, investments, and physical recoveries, the ultimate project for Liu is one of personal emotional healing.

In 2021, he was interviewed for an online edition of Smile Train’s annual Cleft Con. Toward the end of his segment, his interviewer asked for parting words.

“When you have a cleft, you really feel alone. And you wonder, ‘will I always be alone,’” Liu began. His voice cracked slightly as he spoke about meeting his wife and having his family.

“You will find love,” he assured the audience, briskly wiping away the tears that had begun to escape his eyes. He laughed and said incredulously that it had been about 35 years since he had last cried. He realized then that he was not fully healed.

When Liu had a video chat with Jary after the screenings to tell him about the impact of Every Day After and to tell him everything would be all right post surgery, the boy cried. Smile Train reports that Jary recently received his second cleft surgery to close his cleft palate – Liu met digitally with the boy before he went under.

Just as for Jary and his loved ones, there will be more to come to terms with for Liu and his family, too.

‘“The gravity of what I had to go through only really hit them in the face when they saw my film,” said Liu, whose older son hugged him tightly after a screening.

“Talking about this, you know, just sharing my story, making this film – these are all things that are just making me more and more whole,” Liu said.

Though in good health, he is optimizing every day like it’s his last – something former isolation, deeply rooted health care needs, and major surgeries have taught him to do.

“What the cleft has really made me do among a lot of other things is, I really do live my life,” he said.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are currently funded by our readers and such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.’

Find additional content on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram , Tiktok, X, and YouTube. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a tax-deductible donation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.