By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

How and why Koreans first began coming to America

2023 marked the 120th year of Koreans in America.

The first wave of formal Korean immigration to America began with 102 laborers who deboarded at Pier 7 in the Port of Honolulu on Jan. 13, 1903, long before Hawaiʻi was made a state.

The Koreans were escaping poverty, social turmoil, and Japanese colonization. They were also the next hope for American sugarcane and pineapple plantation owners who could no longer import cheap labor from China and Japan.

Plantations had begun putting people from Asia to work since before the U.S. annexed the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1898. But the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by the U.S. in 1882 cut off the companies’ access to laborers from China. And by the early 1900s, Japanese workers had grown strong enough to demand rights from their employers.

The corporations looked next to the troubled Kingdom of Joseon, as Korea was then known. At the time, China and Japan were vying for control over the Korean peninsula.

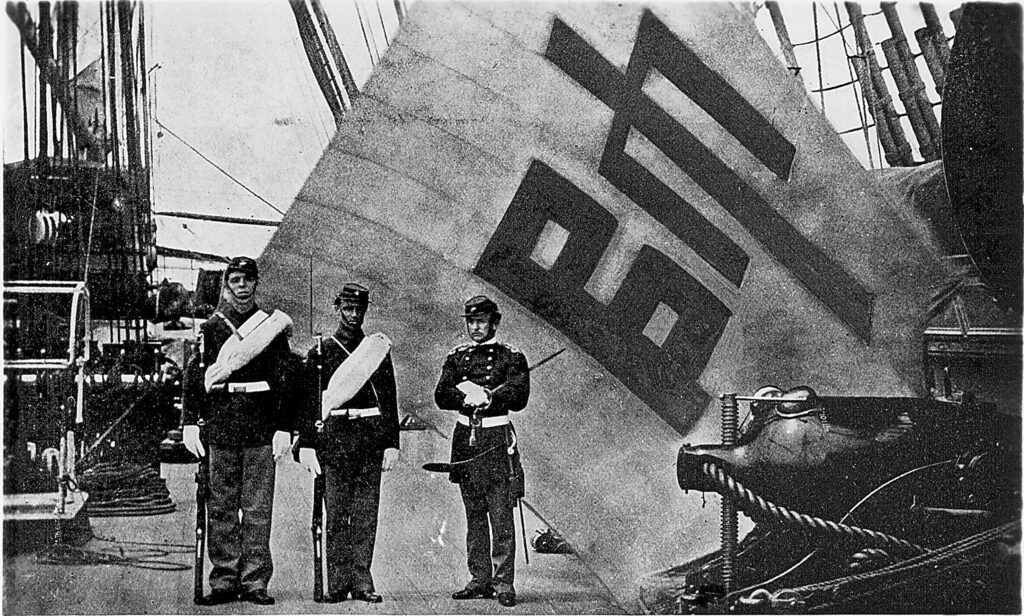

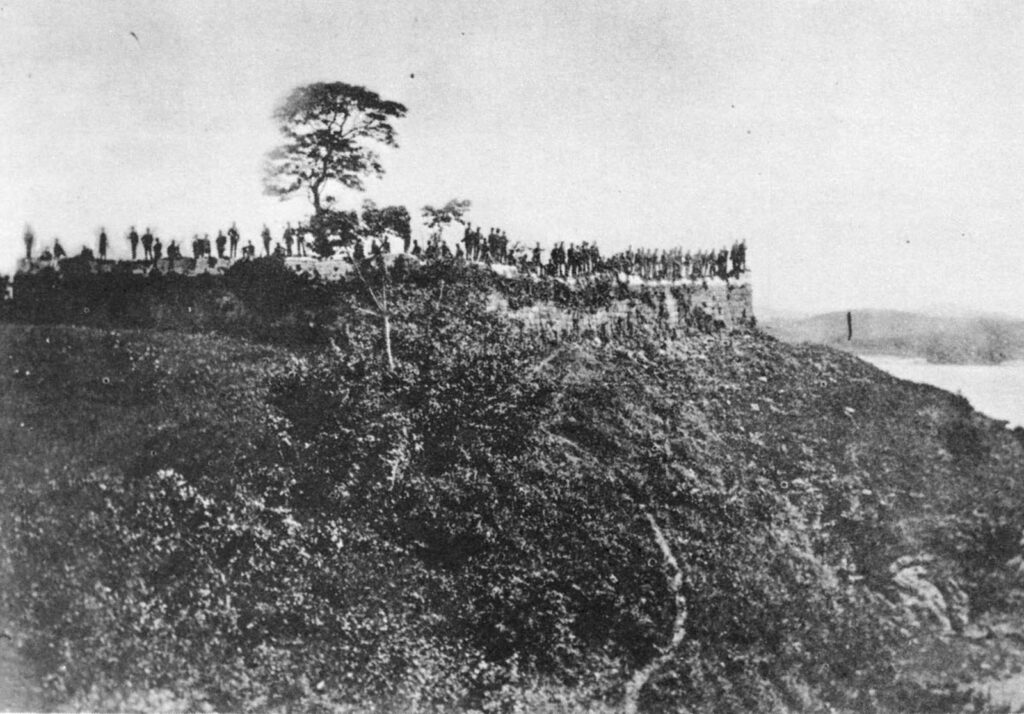

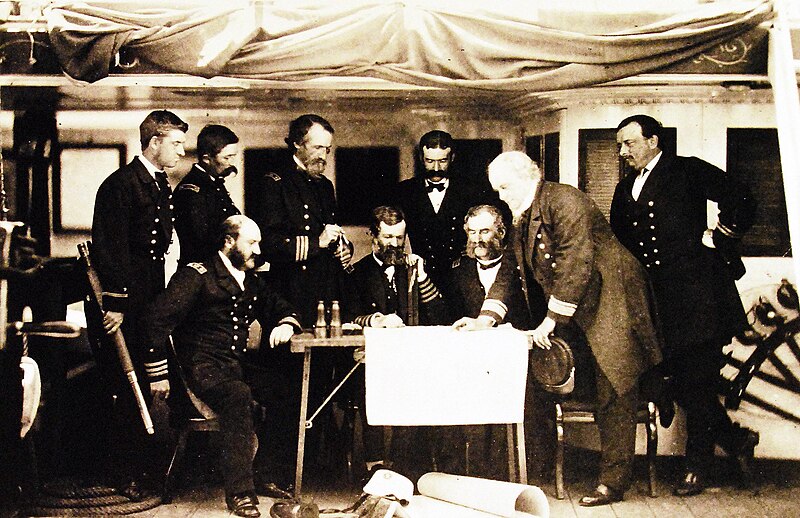

Joseon had also had scuffles with the Asiatic Squadron of combined U.S. military forces. Out-weaponed Koreans had already died in droves trying to defend its “Hermit Kingdom” from American expeditions interested in exploiting economic opportunities in Northeast Asia after the British and French began backing out of the area.

Public domain images of American interactions with Joseon, including pictures of the Sinmiyango ‘Western Disturbance’ in 1871 – Koreans’ first military engagement with the U.S. and its Council of War – nicknamed by U.S. armed forces as a ‘Weekend War,”‘converted Christians in Korea, an early Korean immigrant family in Hawaiʻi, and Koreans in Hilo on Hawaiʻi Island. Foreground: Joseon captives during Sinmiyangyo. Photos by Felice Beato, National Museum of the U.S. Navy.

In 1882, Joseon signed a Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation with the U.S. – one that allowed the first Korean movement to America and Hawaiʻi. Later, on Nov. 5, 1902, Korean Emperor Gojong granted Horace Newton Allen, an American missionary-turned-diplomat, permission to recruit Koreans to the islands.

The first batch of Korean voyagers set out from Jemulpo, Incheon on a ship bound for Honolulu, 4,000 miles away. Those who passed a physical fitness test at a stopover in Nagasaki, Japan endured 22 days sailing across the Pacific Ocean before arriving at their destination. Women and girls followed, mostly as picture brides. Between 1903 and 1905, over 7,000 Koreans populated Hawaiʻi.

This year’s perennial commemorations of Koreans in Hawaiʻi welcomed two full-length documentaries bringing unknown and forgotten history back to life.

Songs of Love conveys the hopes, hardships, and perseverance of the early Korean immigrants in Hawaiʻi with musical performances, scenery, animation, rare archival footage, and voiceovers in place of conventional sit-down interviews.

Unfinished Story follows a Korean celebrity as he salvages names of the departed at gravesites and pores over documents with historical experts to help honor unsung heroes of the Korean independence movement for liberation from Japan.

Singing the everyday existence of the earliest Korean Americans

Songs of Love is a documentary directed by Jinyoung Lee Won, a South Korean journalist and filmmaker who visited the islands in 2005 and decided to stay.

The film expands on Words of Wisdom from the Rainbow State, her series of oral histories from Hawaiʻi’s first Korean immigrants.

Won’s new film opens with a flyover of the barely preserved Puʻuiki Cemetery in Waialua, where 36 Korean plantation laborers’ families lie in eternal repose under sun bleached tombstones. French Korean violinist Ignace “Iggy” Jang, concertmaster of Hawaiʻi Symphony Orchestra, plays Song of Hope, sung by Koreans after the deadly failure of their bid in 1919 for freedom from Japan.

Jang continues with When Spring Comes, performed outside the acoustically resonant state capitol building in Honolulu while a montage highlights never-before-seen pictures of distinguished Koreans, including late Hawaiʻi state supreme court chief justice Ronald T. Y. Moon and three-term Hawaiʻi County mayor Harry Kim.

The episode closes with Jang playing Evergreen Tree under a rainbow aboard the Republic of Korea Navy’s Marado ship docked at Pearl Harbor as archival images of Chinese, Portuguese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrants of Hawaiʻi fade in and out of the picture.

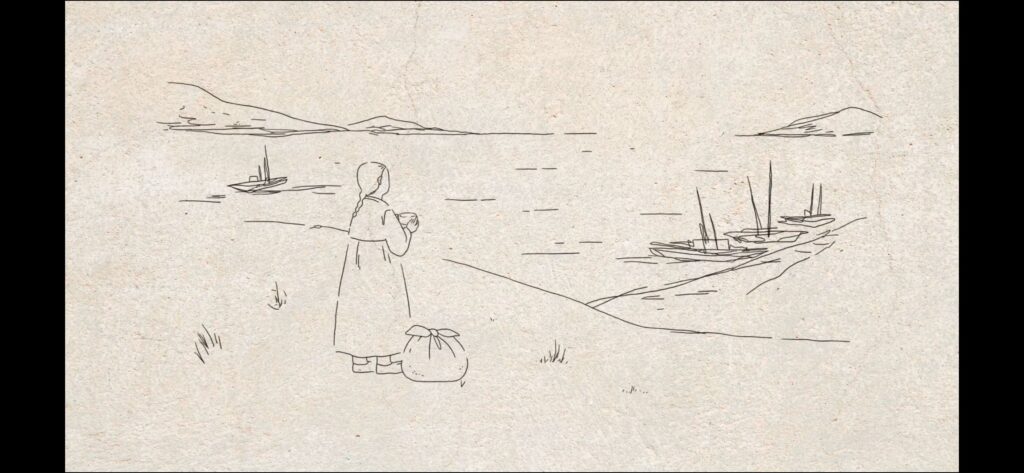

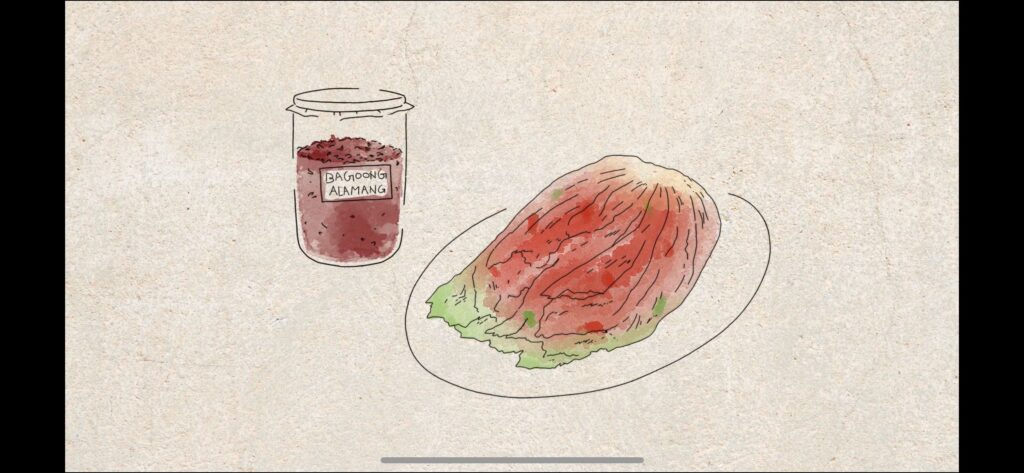

The second portion of the film tells the tale of Lim Ok Soon, a Korean woman orphaned as a little girl after Japanese authorities killed her parents for their activism. When Lim decides to become a picture bride in Powa, as Hawaiʻi was then known to Koreans, her caretaker sends her off with a brass bowl to keep full of rice.

A poignant animation by Korean designers Nam Hoonil and Kim Dasol plays along with a voiceover by an actor portraying Lim. Another voice is that of Lim’s grandson – third-generation Korean American Gary Pak, whose grittily real yet hauntingly surrealistic writing has infused the canon of modern literature with Korean American and Hawaiian American spirit.

Pak speaks about his halmeoni (grandparents) as photos of his grandmother and him play on screen. Later, he kneels at Lim’s resting place and helps his baby granddaughter sprinkle rice from her old brass bowl onto the grave.

Emmy and Grammy award-winning violist Richard Yongjae O’Neill, also of Korean descent, provides stirring musical performances from the low tide of Kuliʻouʻou Beach Park where Lim first landed in 1905 and at the foot of the majestic scenery of Kaneohe, where she often brought her grandson.

The concluding episode honors people exiled to Molokaʻi’’s Kalaupapa leper colony from 1866 to 1969. Out of the 8,000 people of diverse backgrounds who lived and died in isolation on Kalaupapa during this time, 57 were Korean.

Jang reappears with his violin at the seaside Papaloa Cemetery with Korean string musician Chee-Yun and renowned slack key guitarist Keola Beamer. In the hallowed grounds of a community where only eight people continue to reside, the musicians perform Going Home Where the Clouds Float Away, melding Where The Cloud Roams with Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 From the New World.

The musical finale is Aloha Oe (Farewell To Thee), a composition by Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last monarch of the Hawaiian kingdom.

Director Won wrote to AsAmNews, “The reception to the screening was truly heartwarming. The audience’s emotional connection to the stories and the music was palpable, and it made the premiere an unforgettable experience.”

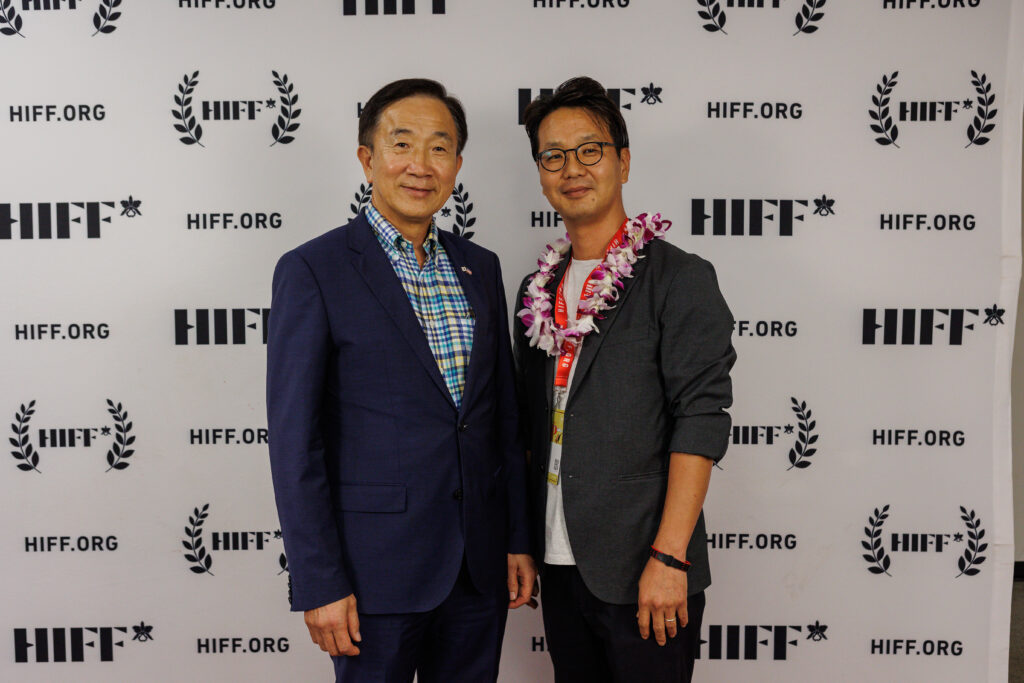

She said that the attendees of the international premiere of Songs of Love in October at the Hawaiʻi International Film Festival (HIFF 43) shared their personal stories and asked how to find the music, prompting the team to plan the future release of a CD soundtrack.

Unearthing Korean patriots from Hawaiʻi’s graves

The second documentary, Unfinished Story, also had its international premiere in its back-to-back screening with Songs of Love at HIFF 43. The film is a joint production of the KBFD independent Asian content channel in Honolulu, directed by Jeong Tae Lee and Byung Choon You.

After two years of reporting, the film unveils that the early Koreans in Hawaiʻi, like their handful of predecessors on the mainland, were not only immigrants, laborers, and survivors, but also freedom fighters for Korea’s independence from imperial Japan.

In 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Treaty of Portsmouth, allowing Japan to do what it wished in Korea in exchange for letting American interests have free reign in the Philippines.

Subsequently, Japan colonized Korea from 1910, not to leave until the end of World War II in 1945. Since then, the Japanese government has systematically minimized, erased, and denied its colonial history.

One way that Korean community groups and the South Korean government is attempting to upright this is by identifying and honoring Koreans independence advocates who lived in Hawaiʻi. Unfinished Story gives the audience an intimate look at these efforts.

The living protagonist of the film is Kim Seung-woo, an award-winning Korean actor and TV talk show host known globally for works like K-drama and film Iris and the Iris II sequel. He also happens to be a descendant of Kim Tae-ho, a Korean activist who fought against Japanese colonization.

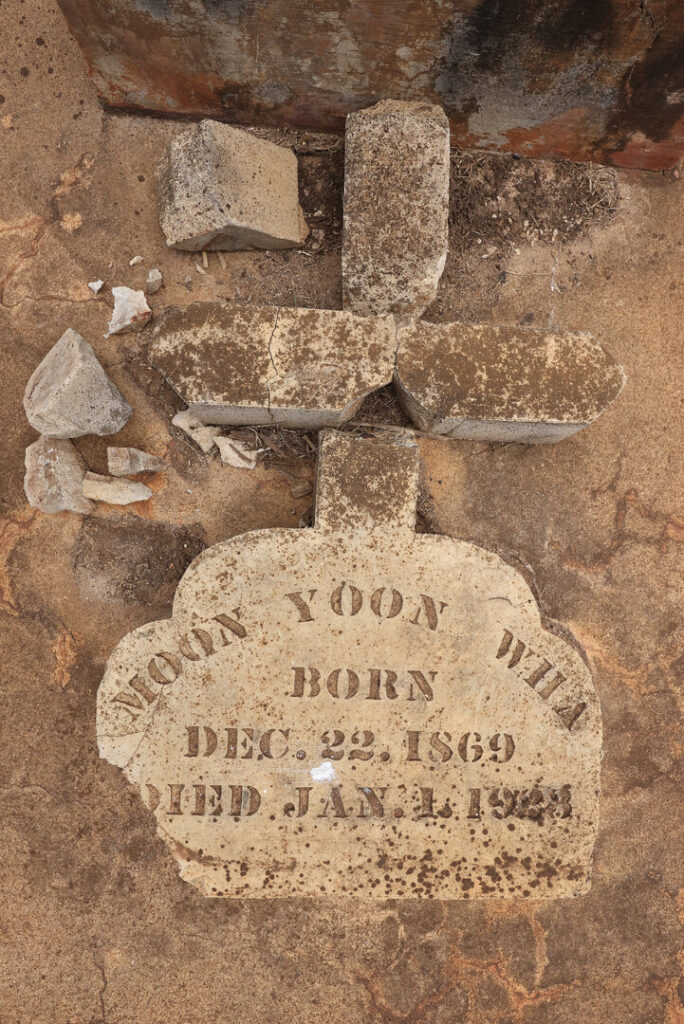

Upon an invitation by Seok Dong-hyun, Secretary General of The Peaceful Unification Advisory Council Hawaiʻi and the Christ United Methodist Church of Maui, Kim travels to the islands to participate in the Tombstone Rubbing Project.

The project, an initiative of the Korean American Foundation Hawaiʻi, preserves names from the dilapidated headstones of Koreans buried in the islands and immortalizes the life stories behind these names.

While making etchings of faded and cracked gravestones alongside artists and other Koreans in Hawaiʻi, Kim also talks with historians and notable descendants of the earliest Korean immigrants.

Kim Sang-yul, the director of the Museum of Korea Emigration History in Incheon, describes the Korean plantation workers’ lives in Hawaiʻi – a 4:30 a.m. wake-up call by siren followed by 10-hour workdays under the hot sun with half an hour in the middle of the day to eat their packed lunches. The laborers received $15 to $20 a month for their 6-day weeks.

Baik Tae-ung, director of the Center of Korean Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, shares in the film that the Korean laborers refused being listed as Japanese citizens in Hawaiʻi and chose instead to live as “men without a country” so long as Japan remained in Korea.

He says, “They thought that the way to confirm their existence was the process of helping the country achieve independence.”

Unfinished Story enumerates Korean leaders, organizations, schools, and fundraising initiatives in Hawaiʻi that supported Korea’s independence from Imperial Japan from half an ocean away.

The Hawaiʻi Hapseong Association, an anti-Japanese nationalist organization championing sovereignty in Korea, bloomed into 47 branches across the Hawaiian Islands after its establishment in 1907. The formation of the Korean National Association (KNA) followed in 1909, to give Koreans a self-governing body across the Americas.

A catalyst for this expansion was when two former Korean patriots and laborers of Hawaiʻi, Chang In-hwan and Chun Myung-woon, assassinated Durham White Stevens, on Mar. 25, 1908 in the San Francisco Ferry Building.

While on a tour in the U.S., Stevens, an American employee of Japan’s ministry of foreign affairs, had told newspapers that Japanese colonization was an improvement to the backwards and corrupt society of Korea. He had said that Koreans welcomed the invasion and neglected to mention the genocidal practices of Japanese officials and troops being applied to them.

Filmed among archives, Duk Hee Lee Murabayashi, president of the Korean Immigration Research Institute in Hawaiʻi, tells the actor Kim about how the Korean diaspora in the islands gave money for the defense trials of the assassins.

Donations from Koreans in Hawaiʻi ranged from 25 cents to 10 dollars, up to half of a monthly salary at the time. By 1909, the KNA was collecting 5% of participating supporters’ income directly out of their wages.

Koreans in Hawaiʻi also gave their earnings to the trial of independence leader Ahn Jung-geun after he assassinated Itō Hirobumi, the first Prime Minister of Japan, on Oct. 26 of that same year. Ahn was ultimately hanged by the Japanese government; the Republic of Korea posthumously gave highest honors to the martyr in 1962.

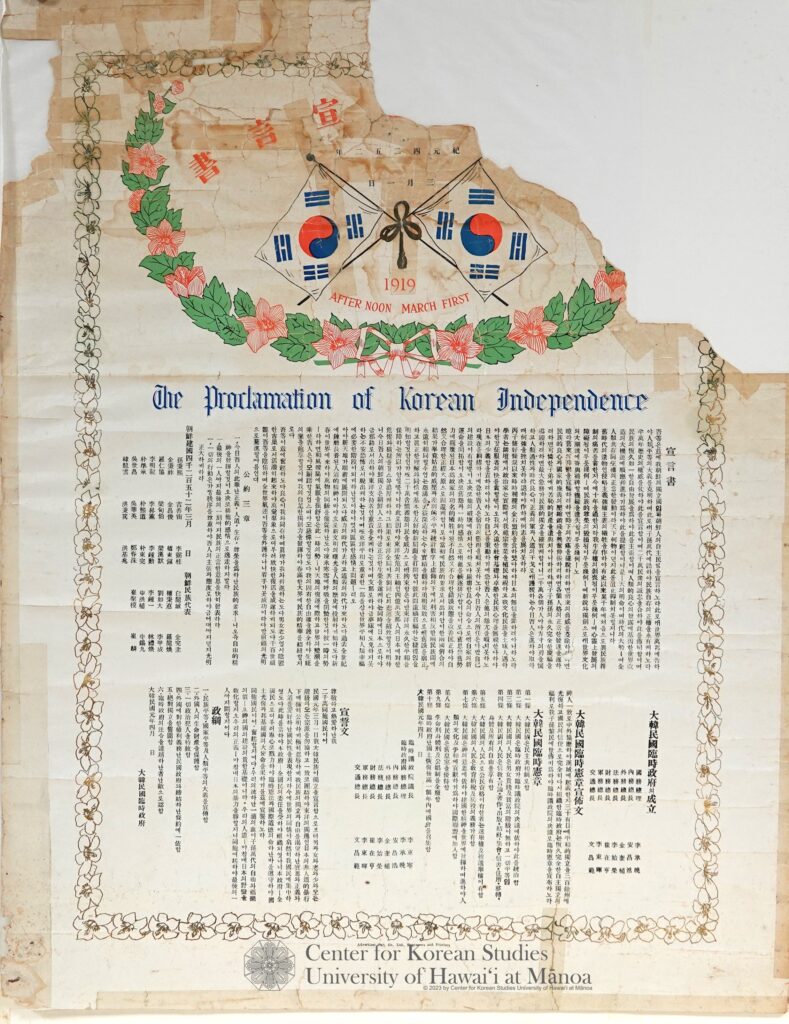

A decade later, on Mar. 1, 1919, 33 Korean leaders set up a provisional government in Shanghai and declared independence in an event remembered as the Samil (March 1st) Movement. Japan killed over 7,000 Koreans and destroyed irreplaceable Korean cultural sites to suppress the demonstrations that followed.

Koreans in Hawaiʻi responded by designing, printing, and selling posters with the Korean Proclamation of Independence printed on it. With this and other efforts, such as donations of nearly half of laborers’ monthly salaries, Hawaiʻi’s Koreans raised $35,000 – over $600,000 in today’s dollars – for aid to Koreans.

They also supported a Korean delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, though the representatives’ pleas for independence were ignored by the international community. They also threw a parade in Honolulu, becoming the only Koreans in the world to celebrate the independence movement on the year it occurred.

In the film, Lee Murabayashi shows Kim an original proclamation poster, a Korean flag hand-sewn in Hawaiʻi, and a registry with 4,000 names of Koreans in Hawaiʻi who backed freedom fighters in Korea.

Minister Park Min-shik of South Korea’s ministry of patriots’ and veterans’ affairs says in the documentary, “We cannot remember if we do not make a record of it.”

Until recently, Park’s department, responsible for honoring and commemorating Korea’s heroes, defined patriots as those who have been imprisoned for three months or more or been in combat for Korea. The requirements have been evolving to encompass women, non-military Koreans, and the diaspora in Hawaiʻi and elsewhere.

Koreans and Korean Americans are helping find more and more everyday people and independence fighters of Hawaiʻi to be honored and remembered.

Unfinished Story concludes by showing the tombstone rubbings on display at an exhibition by the Mayor’s Office of Culture and the Arts in Honolulu before they enter the Independence Hall of Korea.

The quest to make Korean Hawaiian history known and remembered

Approximately two million people of Korean descent reside in the U.S. today – a quarter of them live in Hawaiʻi. But unless directly related to the first Korean immigrants to the U.S., most still do not know about the history covered by Songs of Love and Unfinished Story. The documentaries are trying to change this.

KBFD has continued approaching film festivals around the U.S. to distribute Unfinished Story after airing the documentary on its public television network.

Meanwhile, Songs of Love went on after its Hawaiian premiere to screen at the 2023 Council on Korean Americans (CKA) Gala on Oct. 28 in Washington, D.C. and the “40 Years of Belonging” gala of the Los Angeles chapter of the Korean American Coalition (KAC) in Los Angeles on Nov. 11.

In an update shared to AsAmNews, Won said that the film team is actively seeking various screening venues and entry to festivals while pursuing TV and streaming distribution in the U.S., Korea, and beyond as they finalize the film.

Those wishing to learn more about and support the distribution, promotion, and sharing of Songs of Love to a wider audience can visit the donations page of Now Production Films, Won’s documentary studio.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are currently funded by our readers and such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.’

Find additional content on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram , Tiktok, X, and YouTube. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a tax-deductible donation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.