By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.

Before she came to understand the symptoms of depression, Erika Mey thought she was lazy when she had trouble getting up some mornings. Feeling insufficient and even worthless despite her best efforts to be useful led her to the conviction that the world would be better off without her.

Science has shown that trauma trickles down through generations, affecting biology, mental health, emotions, and relationships. But Mey, born in the U.S. to parents who fled Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge genocide, did not realize the symptoms of anxiety, depression, and complex PTSD until young adulthood.

“You can just be sitting there and then all of a sudden it’s just like, oh, this reminds me of when I was little and this and this and this happened,” she said, in a conversation with AsAmNews.

Mey’s hyper-alertness and anxiety were learned behaviors. Her mother once jumped at the sound of a dumpster hitting the ground outside because the noise reminded her of gunfire. Both parents worried whenever Mey was out after nightfall.

The mental health experiences of Mey, her family, and other Cambodian Americans are often hidden within the aggregate Asian American narrative. Drawing from her own exposure to intergenerational trauma, Mey works to illuminate the challenges faced by the oft-marginalized Cambodian and Khmer communities and inject them into broader discussions about mental health and well-being.

What aggregated data hides and disaggregated data reveals

Cambodian and Khmer people and their experiences remain largely excluded from studies, policymaking processes, public messaging, and journalism because of their small numbers and lack of focus on their unique refugee journeys.

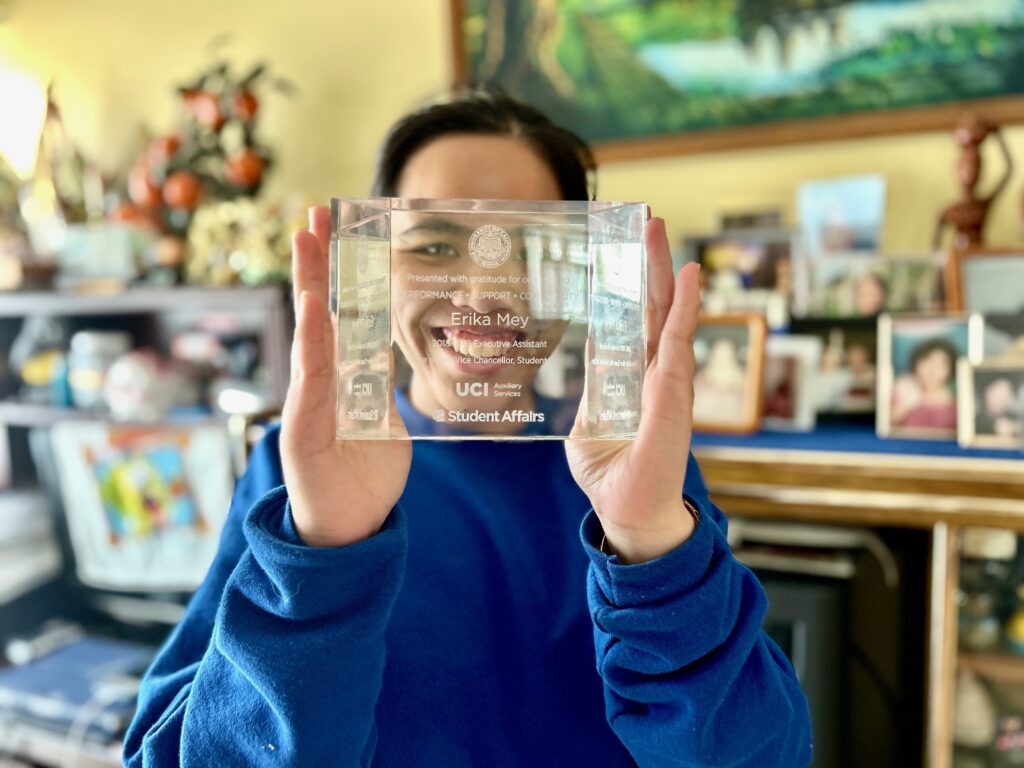

As a public health Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Irvine (UCI), Mey, 27, is among 5.9% of Cambodians in the country over 25 years of age who possess a graduate or professional degree.

She knows that data disaggregation and acknowledgment of trauma are required for American society to understand the realities of Cambodian and Khmer people.

Mey took on the task of designing and conducting disaggregated research necessary to find data-informed solutions to her community’s social problems.

Early last year, she responded to a call for a doctoral-level researcher of Cambodian American descent to help with a community-oriented study.

She got the job and joined a team led Dr. Peter Keo, the Cambodian American founder and CEO of the award-winning, minority-owned market research firm Rapid Research Evaluation (RPDRE).

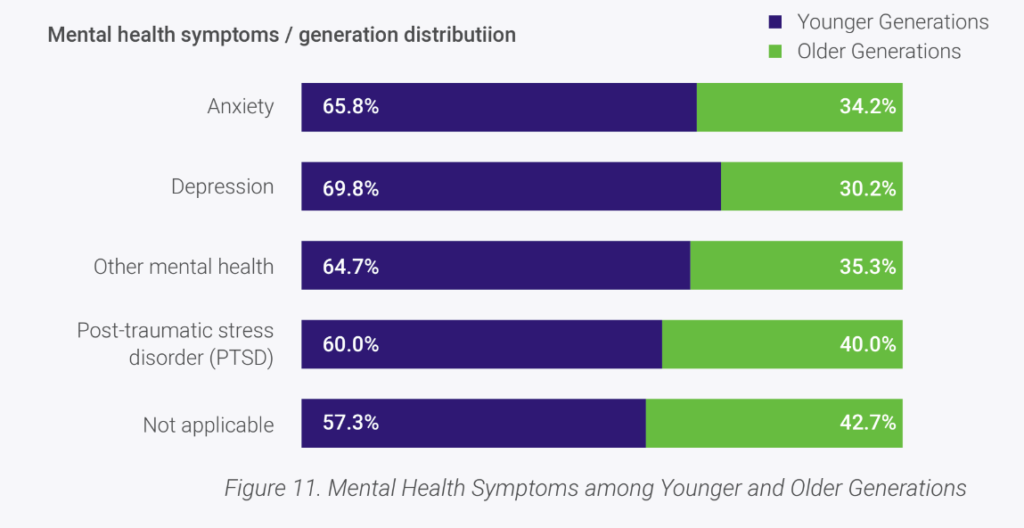

The resulting report, The State of Khmer Americans in Contemporary Society, revealed that about two-thirds of first generation Cambodian Americans like Mey live with anxiety (65.8%), depression (69.8%), PTSD (60%), or another mental health condition (64.7%).

Older Cambodians reported lower rates of anxiety (34.2%), depression (30.2%), PTSD (40%), or another mental health condition (35.3%) in comparison to younger generations, possibly due more to conceptual gaps on the part of the elders rather than better mental health status.

As major of a problem that intergenerational trauma is in the Cambodian American community, the research measuring it is infrequent and often accessed only by a small segment of society in academia and health.

The circumstances that drove Cambodian and Khmer people to the U.S. underlie the socio-economic challenges they have faced ever since. These differences become invisible when averaged across a general “AANHPI” experience.

The 2022 American Community Survey counted 280,862 Cambodians in the nation (0.08% of the U.S. population) and 93,847 in California (2.4% of the state’s population). Their small numbers have been met with persistent lack of focused research about the community even as calls for disaggregated studies about Asian groups increase.

Mourning past losses on the way to future intergenerational healing

Mey’s research activities increased her desire to capture the experiences of the people closest to her – those who were living with the originating trauma in her community.

She had analyzed the experiences of hundreds of Cambodian Americans but had yet to document the details of her own family’s stories.

She decided to formally interview and record her mother. She was glad that she could speak Khmer – most of her cousins and Cambodian peers had lost the language, further disconnecting them from their elders’ narratives.

On a Monday morning in April, on the eve of the Cambodian new year, Mey stooped over a chair in the L.A. apartment where she lives with her parents and younger brother. She propped up her smartphone on top of a shoebox on the seat and focused the camera on her mother, Khao Poy Keang, in her early sixties, who was sitting on the couch with her hands folded in her lap.

Before Mey hit record, Khao stood on her tiptoes to reach photographs and paintings stacked in containers on top of a bureau. She had pulled these treasures out of her bedroom for this moment.

She brought down and held up a painting of her mother, who died at age 38 of unknown sickness while Khao and her siblings were at their assigned labor camp away from their parents.

A white vinyl folder contained a portrait of a handsome young man – Khao’s eldest brother who had been killed by the Khmer Rouge. Underneath this was a smaller picture of two of Khao’s younger sisters. One of them had died of starvation in Khao’s arms. Another younger sister, unpictured, had been killed, too.

A photo of 14-year-old Khao sat in its own protective plastic sleeve, its edges speckled with water damage from raindrops that had fallen during the exodus from Cambodia.

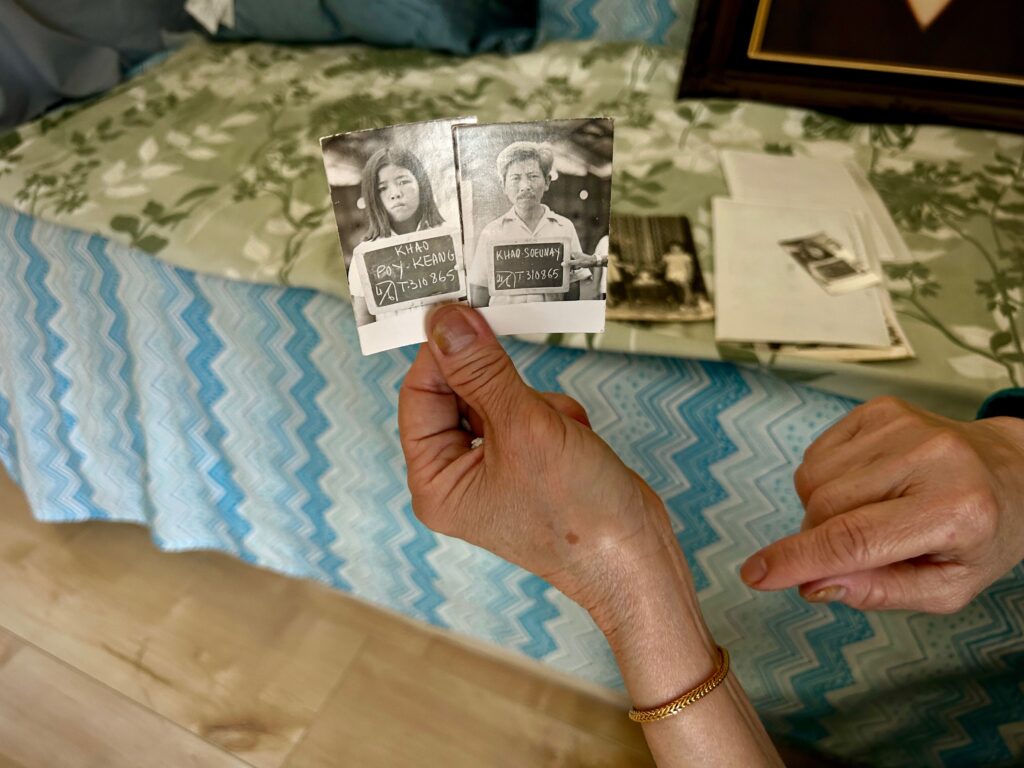

There was also a refugee camp intake photo of Khao herself, holding a sign with her name on it. A similar shot existed of her father, who had reunited with his surviving children after the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

Khao Poy Keang and her father, Khao Soeunay, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979. Photos by Jia H. Jung

Photos taken in the U.S. crowded the top of an armoire housing a tube television, plus glassed-in shelves of figurines, snow globes, and other memorabilia on its flanks. More mementos of Mey and her brother hung from the walls and stood between towering trophies and medals awarded for performance in basketball, kung fu, and Chinese lion dancing.

Mey had never seen the photographs from Cambodia and Thailand that her mother was showing her now.

When the interview commenced, Khao murmured in Khmer that she didn’t know where to begin before speaking more steadily, the toes of her bare feet curled against the immaculate wood floor.

At first, she sounded like she was delivering a recitation but soon became more animated.

She ran out of breath in many portions, gesticulating with her hands – scissors cutting cloth, things flying in the sky, knives slashing across the abdomen. A couple of times, her voice cracked.

When her mother cried, Mey turned incrementally toward her but did not reach out physically, as if pinned in place by the words she was hearing.

They laughed together once, when Khao listed the only English phrases she knew when she arrived to America: “Hello, how are you, good morning, and see you tomorrow.”

After the filming stopped, Khao went on.

She spoke of an elder who had died clutching an empty bowl to his chest, begging people who had nothing for food.

She shuddered as she recalled a real-life bogeyman of the Khmer Rouge whose eyes were always red from eating the hot entrails of the people he killed. As he stalked the streets for his next, everyone tried their best to hide.

Khao said, “I said I’m not going to cry, but the tears come.” Face crumpling, she said, “I still miss my mom.”

Khao said that she noticed much more support out there for refugees these days, but the people who needed the most help – those who were adults during the genocide – were almost all dead now.

Double disaggregation research design

Keo, the research professional who spearheaded the unprecedented study that quantified the extent of intergenerational trauma in Cambodian and Khmer communities, was born in the U.S. and raised in Houston, Texas to Cambodian refugees.

Both Keo’s parents had lost every single member of their families to the killings by the Pol Pot regime. Keo and his siblings grew up enveloped in their parents’ depression and anxiety.

“It’s a part of my DNA now; it’s always there,” he said.

Transcending every obstacle predicted for someone of his background, Keo grew up to become a successful entrepreneur and researcher.

With the help of Mony Nop, a community leader based in Livermore, Keo formed the philosophy of Data Disaggregation 2.0 – studying a specific ethnic subgroup separately from the “AANHPI” block and digging beyond standard indicators to reveal that community’s true needs.

Mey and the rest of the team conducted a literature review and found a RAND Corporation study which cited that 62% of Khmer adults experienced PTSD symptoms and 51% of Khmer American adults were severely depressed in 2005. This was compared to only 3% of the general U.S. population with PTSD and 7% with severe depression.

With this knowledge, the researchers designed survey questions that would hone in on the mental health status of Cambodian and Khmer Americans while also measuring other indicators of success and wellness. They recruited 320 respondents with the assistance of 46 grassroots community organizations.

The evidence of widespread intergenerational trauma exposed by the study and what it portended for Cambodian and Khmer youth and young adults in America alarmed the researchers.

The team’s analysis also revealed that individuals of Cambodian and Khmer descent who struggled with depression in their earlier years were 1.2 times more likely to experience depression when older compared to those who did not display prior symptoms of depression.

Erika Mey’s ongoing mental health story

Mey felt that the research for once reflected her own lived experiences.

She grew up insulated within her nuclear family in Los Angeles, an hour’s drive from the country’s largest enclave of Cambodian Americans in Long Beach. Khmer was her first language, leading to her placement in ESL classes throughout elementary school.

Thanks to enrollment in a special public middle school specializing in higher education attainment, Mey became the first in her family to attend college before advancing to Master’s and doctorate studies, all at UCI.

It was through her academic work and personal friendships that she came to understand how the trauma undergone by her refugee parents had shaped her life.

From a young age, Mey was the English interpreter for her family while struggling to read and communicate in the language herself. She cared for others while fending for herself emotionally. She had no opportunity to grieve her lost childhood – after all, she had never endured anything as bad as genocide or starvation.

Understanding and acknowledging the impact of intergenerational trauma have led Mey and a few other family members to seek therapy and other mental health resources.

Though Mey has healed considerably and knows that she has the will to live, she still gets blindsided by dark thoughts sometimes. The work to end these downward spirals continues.

Dr. Peter Keo’s continuing micro and macro-level quests

Keo has not yet been able to access the type of exchanges that Mey and Khao have begun to have His mother remains unable to speak about her past or its mental health impacts.

Now in his mid-forties, Keo started taking his inherited trauma seriously about a decade ago when he lost his father.

“When he passed away, I felt like he never had the resolution that he needed,” Keo said. He wrote a whole book about his father to cope with the loss.

Keo said that the micro-level progress of intergenerational healing shared by individuals in Cambodian and Khmer communities are critical but that his greatest quest is to bring about “macro,” or systemic, change.

He observed that the policymakers and legislators entrusted with the fate of everyone’s future are ignorant about the struggles of Asian people in general, let alone Cambodian Americans.

He wants leaders and entities to fund, replicate, and adopt the double-disaggregated method of data collection that he showed is capable of quantizing the saliency of intergenerational trauma in the Cambodian and Khmer communities.

When the Asian megagroup overshadows its subgroups

Keo worries that well-funded AAPI-interest organizations might make the same omissions in research that government entities and general nonprofits do when it comes to smaller Asian subgroups.

The Asian American Foundation (TAAF)’s AAPI Youth Mental Health study, being undertaken with Child Trends and other partners, is an example of high-stakes research that Keo is following.

TAAF, which launched in 2021 as a national organization serving the AANHPI community, is one of the highest-funded AAPI-focused philanthropies in history. The organization is currently wrapping up the qualitative portion of its research, which will in turn inform a quantitative survey aiming to be nationally representative of AANHPI youth.

In an email, TAAF representatives told AsAmNews that the project had recruited Southeast Asian Americans, including Cambodians, for focus group discussions.

The organization could not confirm the extent of Cambodian and Khmer participation or the content of their conversations within the landmark youth mental health research.

“We did not collect ethnicity information in our focus groups, so cannot comment on how many may have identified as Cambodian American,” TAAF data and research director Sruthi Chandrasekaran wrote to AsAmNews.

In a follow-up phone call with AsAmNews, Joy Moh, head of communications at TAAF, cautioned that the study was still in mid-flight and that further details would not be available until later this year.

Keo is keeping the pressure on TAAF and other organizations like it that have the motivation, funding, and influence to contribute to better knowledge about underreported Asian people.

“It’s important that powerful and bigger Asian subgroups don’t play into the erasure of underserved Asian subgroups like Cambodians,” he said.

Even when among allies who mean well, it is not easy to be a watchdog for such a small yet particularly impacted community.

But Keo is not going to stop demanding the rigor of Disaggregation 2.0 research that he has shown is feasible to execute and effective in bringing Cambodian and Khmer realities into AAPI and American social narratives.

So the struggles and losses were not in vain

“People like Erika and I, we love our parents and we want to make them proud. We want to make sure that their struggles and their losses and the deaths were not in vain,” Keo said.

Mey said that she is still digesting the interview session with her mother. Her mind is racing with ideas about how to fine-tune future survey questions to better capture the mental state and quality of life of the older survivors who had established her community.

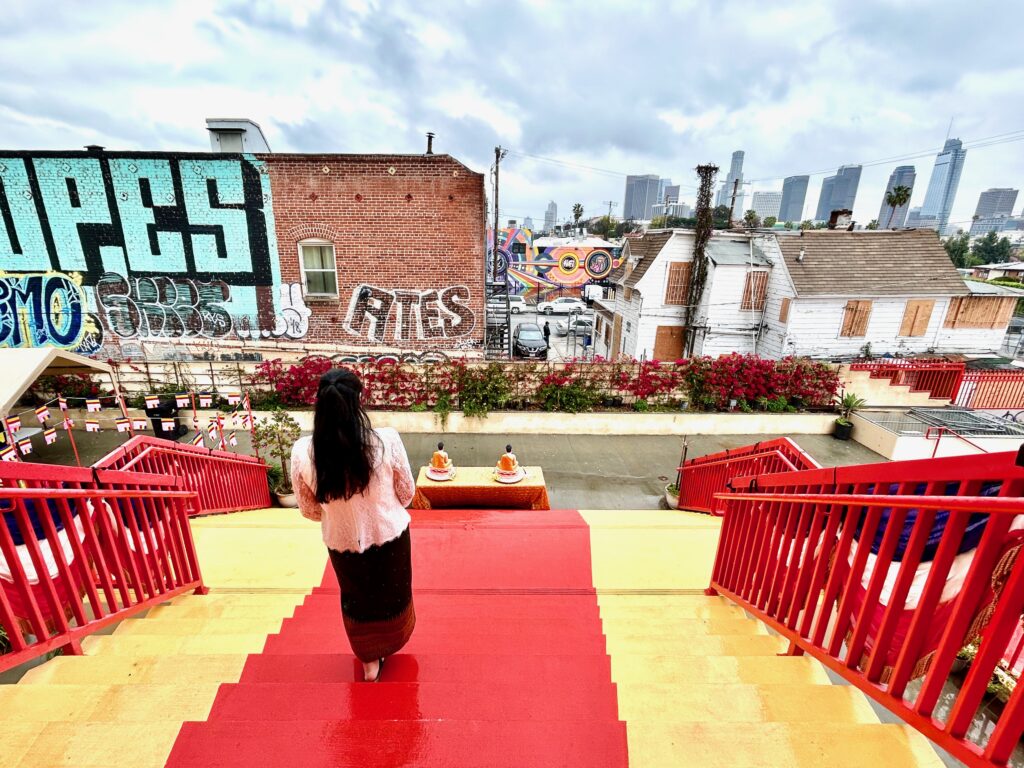

On the weekend, Mey and Khao went together to the Wat Khmer Temple Trigoda Jothignano – the only Cambodian Buddhist temple in the city – to celebrate the three-day Cambodian new year.

They stepped out onto a terrace in the rain and posed in front of an oversized poster of Angkor Wat. The scene appeared to foreshadow their month-long travel to Cambodia in a couple of weeks. Khao’s homecoming will take place after 40 years of absence.

Khao wants to see the pre-genocidal burial ground where some of her ancestors rest. She is prepared to find her village gone by now. But she wonders if the riverside still boasts the natural bounty she remembers from before the terror, in the form of hearty dishes made from a seemingly endless supply of freshly caught fish and just-picked vegetables.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.