By Raymond Douglas Chong

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Until 1942, a tiny Japanese American community in Central California thrived in Guadalupe Japantown, “Gateway to the Dunes,” on the Gold Coast, near Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes along the Santa Maria River. According to the 1940 federal census, 914 Japanese Americans lived in Guadalupe.

Background

The pioneer Issei arrived as farm laborers to toil the rich fields of Guadalupe around 1899. They initially came for jobs with the Union Sugar Company in the sugar beet fields or its plant in Betteravia. They eventually became owners and sharecroppers to harvest the rich crops. They owned farms with their packing sheds.

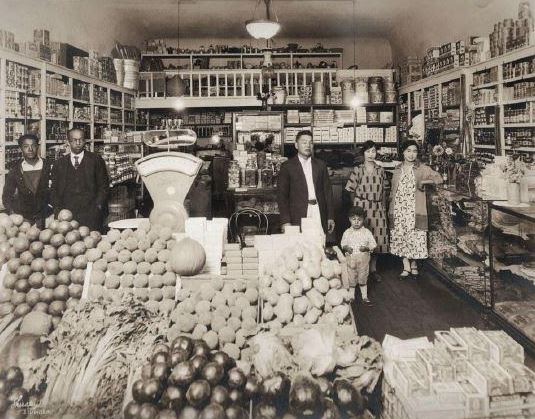

Guadalupe Japantown emerged as a farming center for the Nikkei community. In 1940, 81 businesses and organizations flourished along Guadalupe Street, the town’s main street. They included four hotels, one boarding house, twelve restaurants, three pool halls, three doctors, two fish markets, and over a dozen more stores. They also included the iconic Masatani’s Market, the Guadalupe Buddhist Church, and the historic Royal Theater. The busy produce-packing district was at the south edge of town.

Setsuo Aratani of Guadalupe Produce Company and Yaemon Minami of Minami and Sons, pioneer Issei, operated their produce empires. Arantani was the first grower to ship lettuce from Guadalupe to the market. He developed an agricultural empire of 5,000 acres of vegetables, a chili dehydrating plant, a hog farm, a fertilizer and chemical factory, and an international trade company. Minami was known as the “Lettuce King.” The three large Japanese grower shipping companies were led by Aratani (Guadalupe Produce), Minami (H.Y. Minami & Sons), Tomooka and Tsutsumida (Santa Maria Produce).

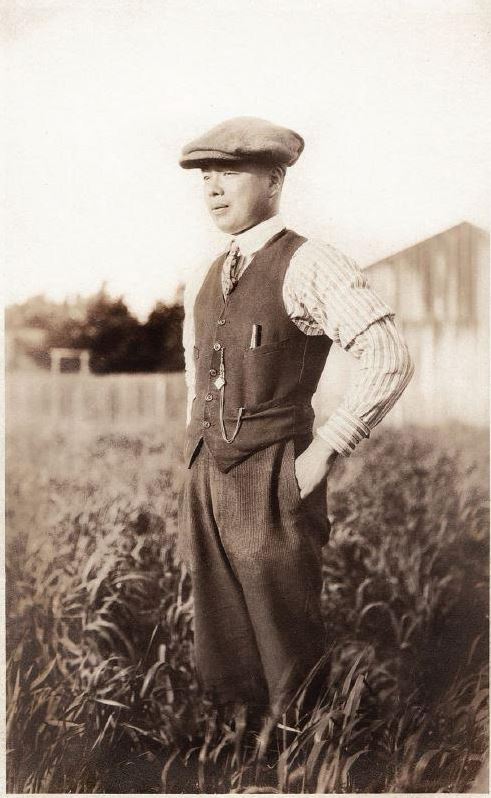

Yoemon Masatani opened Masatani’s Market on 898 Guadalupe Street in 1922 while he operated a trucking business for produce. He catered to Japanese farmers and families from 7 AM to 10 PM every day. He married Teruye Ethel Otha in 1923. They became parents of Harry Yoshino Masatani in 1926 when he was born.

The Guadalupe Buddhist Church began in 1909. Junjo Izumida served as the first Reverend.

The historic Royal Theater is a critical piece of the future Guadalupe Visual and Performing Arts Center.

In his dissertation, Dr. Kent Edward Haldan wrote “Our Japanese Citizens: A Study of Race, Class, and Ethnicity in Three Japanese American Communities in Santa Barbara County, 1900-1960 “ (2000). He noted that the produce enclave in Guadalupe inspired entrepreneurs. Their niche businesses catered to the agricultural sector and Issei single men. He recognized that occupational and employment hierarchy with the associated economic and social relations, along with the Guadalupe Buddhist Church, within the Nikkei community.

Harry Yoshino Masatani is the second-generation owner of Masatani’s Market. Born on August 21, 1926, in Santa Maria, he helped Yoemon Masatani at the grocery store.

Harry Masatani recalled his life in Guadalupe Japantown with Lucia Stone on June 11, 2003, as part of the Guadalupe Speaks Oral History Collection, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California.

Stone: When did you start helping out with the store?

Masatani: Oh, practically all my life. I grew up in the store. You saw that picture when I was about four, five years old.

Stone: When did they open the store?

Masatani: My dad started in 1922.

Stone: Describe what the inside of your house was like? What was your room like?

Masatani: Being an only child, I had the front room facing the Dolcini house. Just normal furniture; gas stove, sofas, tables and stuff like that. We used to have a parrot. My grandma bought this parrot from a sailor in Terminal Island – where the ships come in. Think she paid five dollars for this parrot. She brought it to me when I was born. On the train, she came by train. She missed it so much that she decided she was going to buy another one. She bought another parrot from a Chinese sailor. This parrot spoke nothing but Chinese I heard. [Laughs] That’s the story I heard. This parrot was kind of fun because it would imitate people’s voices, holler out. It was fun having a parrot.

Stone: Your parents – what type of behavior did they expect you to have? What rules did you have to follow?

Masatani: They were too strict on me. No, no. Weekends I got to go to movies. Just a lot of playing: biking, skating. Childhood games; all kinds of games we used to play, like kick the can, cops and robbers, cowboys and Indians, marbles. There was one game called “cut the pie.” We would make a circle in the dirt and we each would have our pocket knife – we’d open it up, flip it and stick it in the dirt. The side of the blade determined where the line was. We drew a line and would try and accumulate as much of the pie as we could. One time it was my turn. I stuck the knife; it went through my friend’s shoe. Right through the leather shoe. I says “Boy oh boy am I in trouble; I must of cut his toe off.” It had gone right between his big toe and the next toe. Not even a scratch. That was the thing I remember. There was a lot of toys. We played with homemade kites, scooters. Stuff like that – just homemade, not store bought.

Marion Perales: You said you went to the movies, where? The Royal Theatre?

Masatani: You know where the Basque house used to be? Geno’s Restaurant? That was the only theatre in town at one time.

Perales: So the theatre before that.

Masatani: Just before the war they built that theatre uptown. I think it was fifteen or twenty-five cents for the theatre. And they’d show a movie and then show a serial. Like ‘Flash Gordon,’ something like that. At the end of the show, he’s about ready to get hammered and it cuts off. It’s continued the next week. So we had to go back next week to see what happened. It was a serial.

Stone: What values did your parents emphasize? Did they emphasize Buddhist beliefs?

Masatani: They weren’t that religious.

Stone: Conservatives?

Masatani: They’re conservatives. They weren’t too religious.

Stone: What kinds of occasions or holidays did your family…

Masatani: We observed all the holidays. [At] Thanksgiving the Merkin Bakery would roast our turkey for us. Christmas we always had Christmas trees. We observed all the holidays.

Stone: Did you celebrate them with your neighbors?

Masatani: Yes, neighbors would come over.

Stone: Fourth of July?

Masatani: Fourth of July was a time for fireworks. Firecrackers. They’re illegal now I think. You know, firecrackers used make a big pop. You know when you light those up.

Perales: What about Obon? Did they celebrate the Obon Festival [inaudible] at that time?

Masatani: Oh, they used to have it here. The Buddhist church used to be on the Guadalupe Street, where the Seventy-Six station is now. They owned a playground where the new one is. It was an open field. I think they used to have it opened there but it got so big they had to move to another area, larger facility.

Perales: Do you remember a typical Obon celebration? When you were growing up did you participate [inaudible]?

Masatani: It’s very similar to what they do today. Sell dinners and dance around, stuff like that.

Stone: I’m assuming that’s a Buddhist celebration?

Perales: She doesn’t know what the Obon is.

Masatani: That’s a Buddhist celebration to remember the people that’s gone. People that died.

Stone: It’s like a festival?

Masatani: Yes, it’s a festival

Stone: Did they have a parade?

Masatani: They have it in Santa Maria. It’s coming up, in fact. If you want to go and take a look you can. It’s free.

Stone: Where was your house?

Masatani: I don’t remember the address – the second house on the corner on Olivera Street. That’s Ninth, Ninth and Olivera. So I grew up in the same block here.

Stone: What was school life like?

Masatani: When I graduated eighth grade the American Legion presented me with an award. It was called American Legion scholastic award. It was presented to me by Henry Dolcini. That’s your grandpa?

Perales: Yes.

Masatani: One more thing. Maybe thirty or forty years later when my daughter graduated from eighth grade she won the same award, the American Legion scholastic award.

Stone: What a typical school day for you? How early would you get up and how would you get there?

Masatani: We walked because we lived just two blocks away from the school. School was fun, recess especially. We played all kinds of games.

Stone: What about when regular school ended? What did you do?

Masatani: We spent an hour or so playing. A lot of marble playing. We used to play for keeps. You’re not supposed to gamble but we used to play for keeps.

Stone: When did you start going to the Japanese language school and what was that like?

Masatani: I think that was once or twice a week. After grammar school we had to march down to the Buddhist Church, where they had a Japanese language school. Our parents made us go whether we liked it or not.

Stone: What was the language school like?

Masatani: It was mostly Japanese kids, but there was a few Mexican kids too, that were interested. Like the Amarillas [sp] girl. They studied Japanese too, I heard. But it was okay. Didn’t learn too much but we didn’t put too much effort into trying to learn.

Stone: Who were your friends when you were young? And what did you do together?

Masatani: One of my best friends was named Patrick. His parents owned a cleaner uptown here. His pictures are in there; I’ll point them out to you later. We used to play marbles and bike riding, skating and all that kind of stuff.

Stone: And is there any particular grammar school memory or language school memory that’s your favorite?

Masatani: Grammar school, but not especially. I remember talking about Mrs. Abernathie [sp], eighth grade teacher. She was known for her twelve-inch ruler. If you did something wrong she would make you stick your hand up; not palm up, palm down. And she would get that ruler and smack you a couple of times. I never got smacked.

Stone: What would be your happiest childhood memory?

Masatani: Just playing, carefree. Bike riding. One time without our parents knowing we took a bike ride out to the ocean, to the beach. That was a no-no. One of the kids was a boy scout and he baked some little hard biscuits. We made biscuits and came back. We’re not telling our parents anything about it.

Stone: Did you get caught?

Masatani: No, we didn’t get caught.

Stone: What is your saddest childhood memory?

Masatani: I’m trying to think, but nothing really sticks out in my mind.

Stone: When was your very first job? And how much did you make?

Masatani: I worked in the store since childhood. But I didn’t get a salary or nothing. My first job was in camp. That’s later on, in the Internment Camp. One summer I worked washing windows at the hospital. The pay was twelve dollars per month. I was figuring out a few years ago how much it was and it came to about four cents an hour. Wow, four cents an hour. [Laughs]

Stone: So did you think Guadalupe was a good place to grow-up?

Masatani: Very nice, very nice place. The depression hit and we didn’t think about it. I guess other parts of the country was depressed but not here. Everything’s normal.

Incarceration

The War Relocation Authority shipped Masatani and his parents to Amache (Granada) concentration camp on a wind-swept prairie in southeastern Colorado near the Arkansas River. The arid land was home to wild grasses, sagebrush, and prickly pear cactus. The prisoners operated a silkscreen shop, cooperative store, and agricultural enterprises.

Masatani graduated high school at Amache concentration camp.

Stone: So your good memories were making lifelong friends while you were there. It was almost fun and free because you were young.

Masatani: It was fun, yes.

Stone: Did you ever have bad memories that stuck out from the camp? Were they violent at all there?

Masatani: No. Things were pretty quiet in our camp. Some of the other camps had troubles. I think some of the guys resisted the draft, stuff like that. They were saying, “Why should we serve when our parents are locked up?” and “Why are you saying the Pledge of Allegiance? Freedom and justice for all seems kind of hollow.” Saying stuff like that. So that’s what some of the objectors were saying I think.

Stone: What would you consider your worst memory there, then? Bad food?

Masatani: A lot of neighborhood kids were dying off in the war. In Italy, next door barrack neighbors. Here and there, all over, you know.

Resettlement

When the Japanese resettled in Guadalupe Japantown after their incarceration in 1945, they found housing challenges. Their properties had all been sold or confiscated. Whites had burglarized or vandalized their remaining properties during their incarceration.

Stone: How long after you left camp did your parents head back to Guadalupe?

Masatani: As soon as the camp closed my dad and mom came back here.

Stone: So was that a year after you left?

Masatani: I left in forty-four and camp must have closed around maybe forty-six; I’m not sure what year exactly. I can’t recall what date.

Stone: How did they get back to Guadalupe and what did they tell you about their experience when they got there?

Masatani: I heard that they came and the government had given them each twenty-five dollars in cash. They got off the train depot and didn’t have anywhere to stay, so they stayed at the old Buddhist Church. They said they weren’t too welcome because somebody shot through the window when they were staying there. Nobody got hurt but somebody did shoot through the window.

Stone: So the community changed?

Masatani: Yes.

Stone: From the time they left, when they were still their friends, to when they came back?

Masatani: I guess these were older people maybe. I don’t know.

Perales: Were other families that came from other camps in the church until they kind of got…

Masatani: Most of them are people that used to live here.

Perales: But your parents weren’t the only ones there. There may have been…

Masatani: There were other families. Families that didn’t have a place to sleep.

Stone: Who in the community helped your family?

Masatani: They just helped themselves.

Stone: Any specific loyal family friends that come to mind?

Masatani: They just made it on their own.

Stone: Was it generally the Japanese community that was helpful?

Masatani: A lot of them kind of stuck together. It was tough starting a new store. Merchandise was scarce after the war. The wholesalers wouldn’t sell to a new store. We were a new store I guess. They had a little bit of trouble, struggle.

Stone: Did your parents ever tell you about anyone making it hard on them? Making their situation harder than what it was? I mean for example, if whoever shot that bullet owned a store…I don’t know.

Masatani: I know somebody shot through the upstairs window too. A few years ago. There was a hole in the window and those old green shades we have up there. There’s a bullet hole there. The bullet was lodged in the wall right above this board of the bedroom upstairs.

Stone: Do you know who did it? Do you know why?

Masatani: We don’t know who, we don’t know why.

Stone: Is it like a BB or a bullet?

Masatani: No, a bullet.

Stone: How did your dad rebuild the store and how did he come up with the money to lease it? Or did he own it?

Masatani: I guess he had enough money saved to start. Just start out small, you know. Gradually built it up.

Stone: Who did he lease the building from this time? Where was it?

Masatani: This time it was the Shimizu [sp] family. Shimizus [sp] used to own some property across the street there. Mr. Shimizu [sp] was an American citizen born in Hawaii so he was able to have property before the war, you know.

Perales: He was able to hold on to it.

Masatani: Yes. Mr. Shimizu used to have a Chevrolet dealership before the war. This was the largest Chevrolet dealership in Santa Barbara at that time.

Stone: When he rebuilt the store, how was it different and how was it the same? [Any] similarities and differences between the first one and second one?

Masatani: Different type of customer. It’s all mostly Hispanic.

Stone: By the time they came back?

Masatani: Most of the Japanese didn’t come back here. Before the war, we’d sell tons of rice. There were hundred pound sacks of rice. We used to get a truck and trailer load, that’s how many hundreds of sacks. There was flower seed company camps all over. We used to sell a lot of rice to Arroyo Grande and Oceano flower seed companies. They would buy twenty-five, maybe more, sacks of rice every so often. [We] would have to deliver. But times have changed. Now we’re selling five pound bags at the most. The biggest. Used to be hundred pounders.

Stone: How did the merchandise change?

Masatani: That’s what I mean. It’s not too many Asian foods, some Filipino and whatever the customers want. You have to cater to the customers.

Stone: Was it less of a mercantile or strictly grocery second time around?

Masatani: Yes, just food.

Stone: Who was your competition then?

Masatani: Campodonico building, “Jeff’s Market.” Then “Homefood Basket,” where the bend in the road is. That was a Japanese store before “Homefood Basket,” come to think of it. Fish market – Paul Kurokawa had a fish market. That’s about it after the war. Oh, another one there where “L.A. Liquor” store used to be.

Stone: No more? Moisho? What was the guy kitty-corner from you? The first round?

Masatani: Oh, Miyoshi? No, their father bought his property on West Main Street before the war and they moved away. You know where the depot street is it? The street through there? Used to have a main street drugstore. One of the sons was a druggist there. They chopped up their property with that road.

Stone: So was it common form, at this time, to have Japanese markets or Japanese business owners?

Masatani: There was only two Japanese: “Homefood Basket” and ourselves, just the two of us. There used to be about five or six. All together there was about thirteen stores when I was a kid. Some mom and pop, some a little larger, grocery stores. I think it was thirteen stores. In a little town like this.

Stone: Where did you go after the service?

Masatani: I came home and helped my dad. I said, “I got this GI bill of rights, might as well take advantage of it.” So I told my dad “I think I’ll go to school.” That’s when I went to L.A.

Stone: When you first came back to Guadalupe, what were the biggest changes you noticed? Since you hadn’t been back since fifteen, right?

Masatani: Hardly any of my friends were here anymore. They were scattered all over. Some in the Midwest, some back East. Most of them didn’t come back at all.

Stone: Who was here?

Masatani: Who was here, let’s see [Pause]. There’s a couple of Japanese families that came back. Maenagas, I don’t know if you know Maenagas. Sammy is a classmate of mine. And Shimizus. Not too many actually.

Stone: Who were the new faces?

Masatani: Not too many Japanese if you’re just talking about Japanese. There were all kind of Hispanics. Some of the Hispanic kids I went to grammar school with.

Stone: Did they then become the majority-minority?

Masatani: Majority-minority.

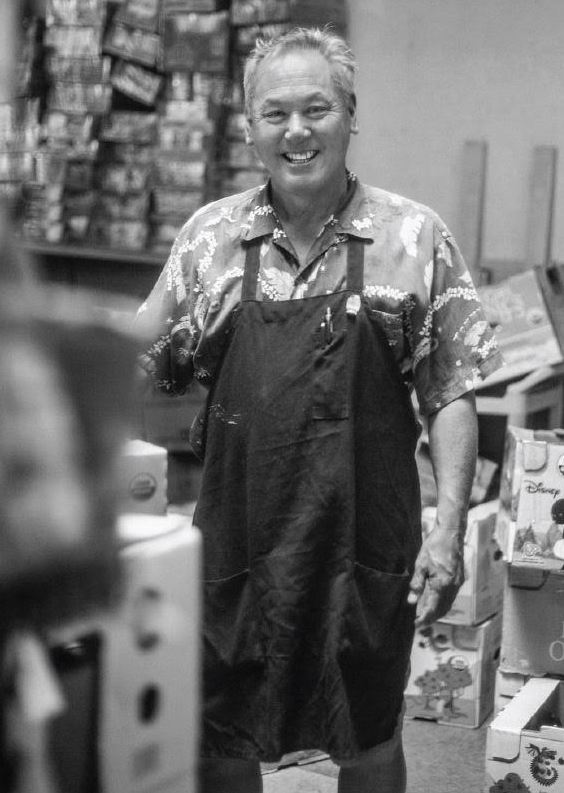

Mastani’s Market

Masatani’s Market is a grocery store that has adapted to changing times. It sells Asian and Hispanic groceries, a wide range of groceries, and market products. Its focus is on quality and variety in its selection of fresh produce, pantry staples, and other grocery items.

Mark Velasquez wrote “Masatani’s Market 1922-2022: Celebrating 100 Years of a Local Treasure and the Family that Created It.”

This book celebrates the past hundred years of Masatani’s Market in Guadalupe, California. The family-run store has been a second home to the residents of the Central Coast, with the name Masatani being synonymous for hard work, reliability, philanthropy, and above all, humility. It is one of the oldest businesses in Santa Barbara County still owned and operated by the family of its original creator. If you are a fan of history and reading about examples of families living the American Dream, you’ll appreciate this personal story.

Valasquez vividly narrates the one-century saga of the iconic Masatani’s Market through three generations: Yoemon, 1st generation; Harry, 2nd generation; Steven, Brian, Tina, 3rd generation. His book covers The First Years, A New Beginning, Steven Masatani, Brian Masatani, Tina Masatani, Time Marches On, A Community’s Loss, The Fourth Generation, Employees, and The Market Today.

Royal Theater

The historic Royal Theater is located within the lost Guadalupe Japantown. It is a rectangular two-story Art Moderne-style building designed with specific Art Deco elements. The Royal Theater can seat 530 people.

Arthur Shogo Fukuda, owner of the Royal Theater, officially opened for business on August 30, 1940. The theater showed Japanese and Hollywood films. However, after the Pearl Harbor Attack, in 1942, Fukuda was forced to sell the building before the War Relocation Authority interned him and Kikuno Okumura, his wife, at the Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas.

The historic Royal Theater is critical to the future of Guadalupe Visual and Performing Arts Center. The Center will expand the arts in Guadalupe by watching movies and live performances, as well as concerts, comedy acts, and musical acts

Garret Matsura, with the Guadalupe Visual and Performing Arts Center, remarked:

While the Royal Theater hearkens back to times gone by, it serves as an inspiration for a prosperous future for the small town of Guadalupe, California. Built-in the late 1930s by Japanese American immigrant Arthur Fukuda, the Royal Theater was one of the prominent landmarks in Santa Maria Valley during the early 1940s. Until then, the Japanese American population was strong and growing within the area. Unfortunately, in 1942, World War II and the subsequent Executive Order 9066 forced Mr. Fukuda to sell the theater. When he returned in 1945, Mr. Fukuda could not reclaim his business.

The Royal Theater continued to operate until 2001 under various owners when it was shuttered after an electrical fire damaged the interior. In the ensuing 20-plus years, many residents have voiced their longing for the theater’s re-opening. Long-time community members recall fond memories of the theater and its place in the community. Most long-time residents have a story about the time they spent at the theater, and for many, the theater is an indelible part of their memories of growing up in a small town.

As Guadalupe continues to rise like a phoenix through community civic engagement and residential growth, the Royal Theater’s recent designation as a National Historic site helped it acquire nearly $10 million in grant funding to help in the rebuilding process as well as new construction for a 3-story visual and performing arts center. Supporters hope this combination of new and old will appeal to historic lovers of the theater and entice the next generation of patrons while sparking economic development within the downtown corridor and the city.

Close

On California’s Gold Coast, the iconic Masatani’s Market, the resilient Guadalupe Buddhist Church, and the historic Royal Theater are the remnants of a lost Japantown in Guadalupe. Since 1922, Brian Masatani, third-generation Masatani’s Market owner, has served the community. The Guadalupe Buddhist Church has nourished Nikkei souls since 1909. The Royal Theater will soon return to its 1942 heyday in the lost Japantown of Guadalupe.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Wonderful story. It would be a good excuse to drive down to Guadeloupe and visit the buildings that are still standing.