By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

A heat wave last week in California turned temperatures in the Central Valley up to 108 degrees Fahrenheit but that didn’t stop musician SOAL (Laos spelled backwards) from driving straight into the triple digit temperatures from his latest base in Long Beach.

Having grown up splitting time in Minnesota, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, and North Dakota, and hot off of back-to-back shows up in Alaska and down in Disneyland, the Lao American artist is used to being on the go. Often, he has his portable studio in tow to work on recordings and music videos from the road.

He has been driving back and forth to Fresno for months now to rehearse with dancers for his set at Sabaidee Fest, happening this weekend from June 14-16 at Prado Regional Park in Chino near Los Angeles this year. The event is being billed as the largest of its kind – the Coachella of global Southeast Asian performers, artisans, vendors, and community organizations.

Salong Namsa, the LaosSupply clothing brand owner and community activist who is the founder and CEO of the event, launched the inaugural edition as a Lao-focused affair last year.

Since then, the planning committee has expanded its scope to include Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Thai, Vietnamese, and multicultural talent, vendors, and organizations in a stacked program this year.

“Last year was to make a statement. This year is to beat that bar that I set and reassure people that I’m not going anywhere,” he said, downing a cool sushi roll prior to rehearsal with Hmong dancers co-led by Kevin Kue. It was a little over a week before his big appearance at the festival on Sunday, June 16.

“You’re about to see the hardship and the passion that the Southeast Asians really have,” SOAL said, leading AsAmNews toward a building where several dance teams practiced under one roof, the various groups’ music bleeding together. He shared his vision of opening a state-of-the-art center for Lao and Hmong dancers and musicians.

SOAL connected with Fresno and its Hmong population last year starting with performances leading up to Sabaidee Fest. After hearing his ditty called Lao Girls, Hmong fans began calling for a version about themselves. He obliged, writing Hmong Girls within the summer, complete with bars crooned in the language he learned for the song.

When he was ready to create a music video for the track, he posted on Facebook to ask where he should film. Hmong Culture and Arts Preservation (HCAP) replied, and before he knew it, he had local Hmong dancers and actresses aplenty for the project.

He also began to receive a constant stream of invitations to appear at Hmong events and showed up just as he had for the Lao community. Witnessing the cohesion of Hmong communities in Fresno and Minnesota, he felt even more energized to bring together the Lao community.

He was mindful of the history between the Lao and Hmong people going back 49 years to 1975, when the U.S. withdrew from Southeast Asia at the end of the Vietnam War.

The Communist Pathet Lao took control of Laos. Communist forces began taking vengeance upon the Hmong men and boys who had been recruited by the U.S. for a “secret war” that killed a tenth each of the Lao and Hmong populations.

For some, nuanced tensions over various divisions lingered, carrying over into the next generations.

Wanting to break the chain, SOAL leaned into his Hmong fan base, paying little mind to the anonymous “keyboard warriors” online asking why a Lao guy working with Hmong girls.

“If I teach them how to be close to one another, that’ll weed out all the OGs who want to spread that toxicity,” he said. If it were up to him, he would put all feuding groups together in song and dance until they had no choice but to find harmony.

“I’ll start with Lao and Hmong first, because that’s what I know best,” he said.

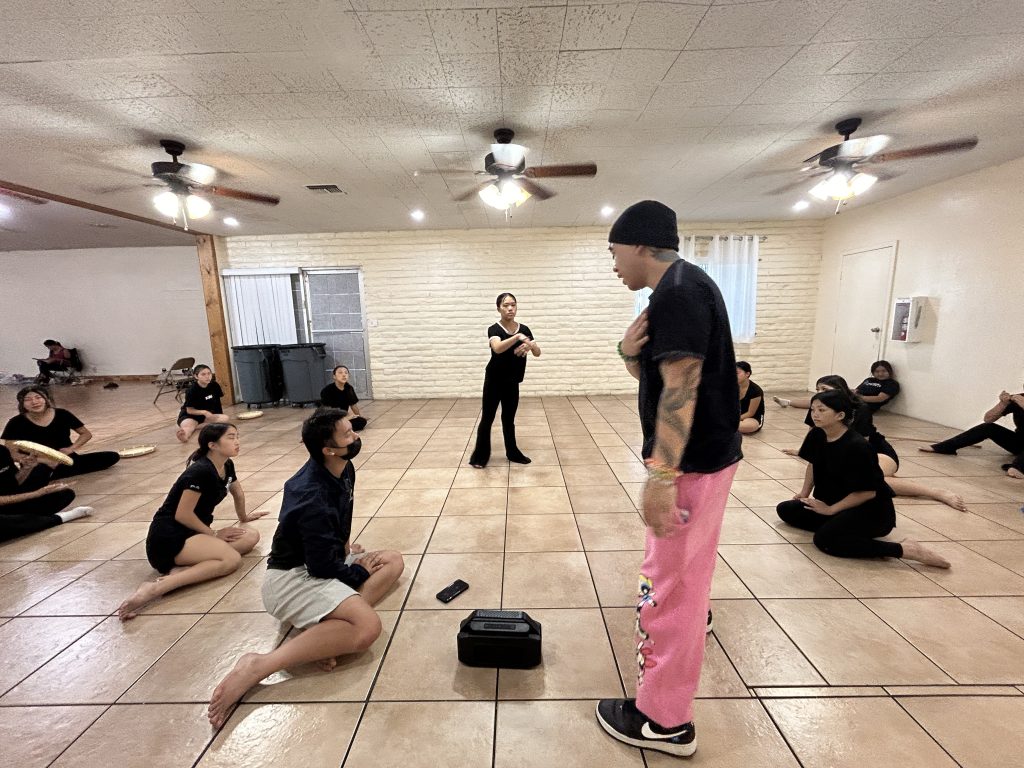

Inside the rehearsal space, Nkauj Hmoob Thswj Xeeb (NHTX), pronounced “gau hmong choo tseng” and meaning esteemed Hmong daughters, awaited SOAL.

The dance team of girls 12 to 16 years old had surprised him just months ago at an event by asking to dance for him when he happened to be seeking dancers again after the group he started off with got called away to an overseas competition occurring at the time of Sabaidee Fest and the next group disbanded.

In clusters, the dancers carried shallow woven baskets and raised traditional dried-grass brooms they were using as placeholder props for plastic hoes that later arrived. They were warming up to learn the rest of a new choreography telling a tale written by SOAL.

Once upon a time, there was a Lao dancing village with a dragon protector. While the village was enjoying a celebration of life and motion, a stranger in a resplendent robe appeared, her face obscured by a sun hat. She began to sing.

The village dragon’s heart froze from the awe of hearing such a sound for the first time. Once his heart thawed, the dragon tried to sing and accidentally burnt down the village. He spent the next 1,000 years taming its fire before returning to protect the village and sing.

“The dragon is me,” SOAL boomed cheerfully, in case there was any doubt that the story is a straight-up allegory for his own life and career. The 31-year-old swore that his life seemed to progress in five-year cycles of struggles and regeneration.

His first love was choreography, inspired by influences like the dance battle movie You Got Served (2004). By his early twenties, he was an underground rapper, traveling to every competition and TV show audition he could to test whether he was worthy of doing music.

He felt marginalized by the hip-hop scene and the music business – not Black enough to feel accepted in a genre invented by Black and Brown people, not White enough to crash the gates of an industry run by people in power, and not rich enough to pay to play.

No matter how he tried, how well he performed, and how much audience respect he received, he just couldn’t place. Agents reached out to him with contracts but asked for full creative rights over his works. It all messed with his head.

Family and friends who were supportive but did not grasp the level of his passion unintentionally said things that only smarted. They advised him to make sure and get a stable job, or to go to college just in case, to have a fallback plan.

“It is always such a bad thing to try to put in a dreamer’s head a fallback plan, because then, subconsciously, they might fall back,” he told AsAmNews in a phone call.

It was hard enough growing up Southeast Asian in parts of America where pockets of his community were few and far between, mostly limited to family and extended family. He recalled wondering how he could become a musical artist in America as a Lao boy, a Southeast Asian guy, when people who shared his heritage were the least seen in movies, shows, music, and games, and mostly as the folks getting killed or playing the villains.

SOAL felt downhearted until he met a woman from a different background who believed in him and prodded him to write and record some tracks. No sooner had he embarked upon the path as an independent music creator did she leave for someone with a profile more like hers, with encouragement from her parents. He said it was “some straight out of The Notebook sh*t,” referencing the Ryan Gosling tearjerker about romance across social divisions.

He could even see their point of view – why should their daughter date a wannabe rapper from a small town who worked at a casino?

SOAL had experienced anxiety and depression since childhood. In addition to what was probably a measure of trauma inherited from his predecessors’ refugee experiences, he said that television opened his mind to music, dance, and aesthetics during his formative years while also filling his brain with terrifying stimuli.

“Seeing post war video clips of dead bodies being rolled into, plowed into a hole, and then the Holocaust – I saw all that stuff at such a young age. It really made me super sensitive and question my understanding of what the world was.”

When as a young adult, he began having breakdowns and suicidal ideation, he could neither find nor afford modalities like therapy. So, he healed by talking with himself – a lot – during long walks in fresh air.

“It was as if creating another personality inside my head, to really just bounce back and forth,” he said.

SOAL also valued the solace of his best friend and his older sister for their life perspectives. “Whenever I really felt like offing myself, she was the one I’d call,” he said, of his sibling.

He wants people to hear this part of his journey because he knows he’s not the only one who has gone through it or is going through challenges like Southeast Asian male identity, interracial love, or the creative process.

He said he was lucky to have a good family. No matter how they worried, they always backed him up in his musical pursuits. In fact, his father had worked before as a traveling musician at Lao parties.

As grateful as he is to have been born and raised in the U.S., SOAL can’t help but wonder whether he or his father would have become famous back in Laos if the family had not become displaced from there by warfare.

Since the world has always been unfair, he figures the only way to make a place for oneself in it is to keep pushing.

“If you’re not good enough, then just get twice as good. If that’s not good enough, get four times as good. If that’s not good enough, get eight times as good,’ he said. He feels that there is no time to complain and that he had to be strong because too many of his family friends were getting old.

A goal that he holds higher than success itself is to build the power to take his loved ones along with him in his successes.

After his performance at last year’s Sabaidee Fest, an uncle who had been an older brother figure to him ran up to him and said that he was proud of SOAL.

“I told him I’m just trying to get to where my dad started, and he said he thought I blew way past him already, which was a really nice passing of the torch,” SOAL said.

Back at practice in Fresno the NHTX dancers took a break, chomping on Cheetos delicately plucked out of an aluminum pan with acrylic nail tips and washed down with pastel Gatorade. Once they resumed their routine, they achieved completion of SOAL’s redemptive dragon dance and erupted into giggles, ultimately breaking formation.

A few parents, all serious, watched silently from the wings. One sternly called out, “Stop laughing and get it together. You only have a few days.”

The dancers tittered some more, as if knowing that they will pull it out once they are on stage and the adrenaline is pumping.

SOAL said that this moment capped off five new dances that the team had managed to learn within a two-month period. He would solo when they had to change offstage – he was fine without a break.

A crisp, bouncy tune began playing out of a boombox on the floor in the adjacent room, where lines of older girls in elevated dance shoes stepped and twirled on better parquet flooring.

“That’s my music,” SOAL beamed. The dancers were learning alternative choreography for another video for one of his songs.

“These girls want to be seen, and I want to help them,” he said, gazing out over the space after greeting departing teams, helping distribute leftover beverages, and take out trash. A little girl squealed his name from the perimeter. He waved.

“Just give it a couple of years,” he said, referring both to his own trajectory and that of the community he wants to bring to the main stage of American entertainment.

He plans on making it and taking everybody with him.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are currently funded by our readers and such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.’

Find additional content on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram , Tiktok, X, and YouTube. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a tax-deductible donation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.