By Kiyomi Casey

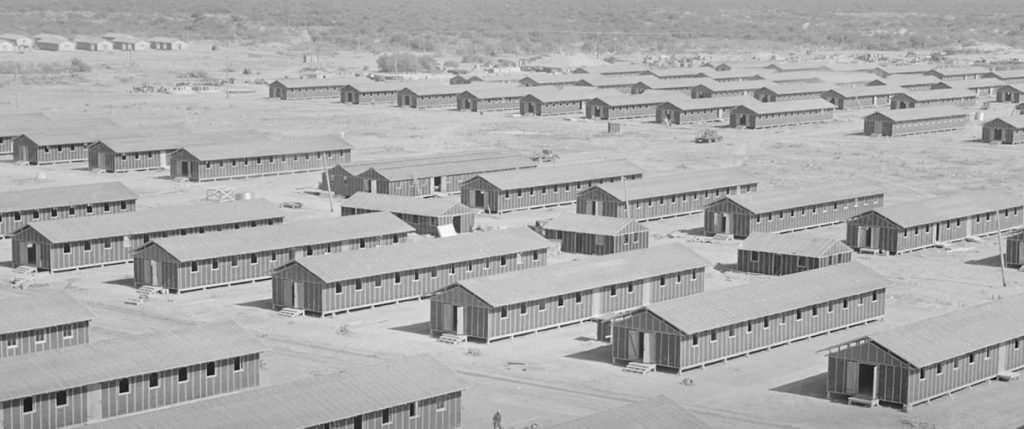

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

“In some ways, in our house, the words were before camp, during camp or after the war. So that’s how timelines were established.”

Those are the words of Janice Munemitsu, a third generation Japanese American, and author of Kindness of Color. Like many Japanese families, her grandfather, Seima Munemitsu immigrated to the U.S. from Japan, and began farming prior to the U.S. involvement in WWII.

“My grandfather now had worked in the Carson Ranch, you know, probably 12 to 13 years and had enough knowledge and saved enough that he would have loved to have bought his own farmland,” she said. “But the alien land was at the time restricted Japanese from owning land because they weren’t citizens. So, he was able to lease 40 acres of property in Westminster from an older woman who was not farming.”

Later, Seima was offered the right of first refusal to own the land he was leasing. But because of the alien land law it would have to go to Seima’s son, and Janice’s father, Tad Munemitsu, who was a U.S. citizen.

“Along the way, when my dad was about eight years old, he started to go to the bank Garden Grove, First National Bank, with his dad, with my grandpa, to kind of translate, you know, English to Japanese and Japanese to English. In the back of his mind, he was probably thinking, you know what, this is a good way for him to learn as well.”

Tad Munemitsu found a mentor in a banker named Frank Monroe.

“My dad said he’s the best friend you could ever have,” said his daughter Munemitsu. “He didn’t have a prejudiced bone in his body. So it kind of tells you what my dad also experienced with other people outside of Mr. Monroe, if that’s what he’s going to say about Monroe.”

Aware of the incarceration happening to Japanese Americans, Tad Munemitsu turned to Mr. Monroe to help him keep the family farm.

“Japan bombs Pearl Harbor. Now I’m an American, but I look like I’m Japanese. So now I’m seen as an enemy because of my name and the color of my skin so what are we going to do? But Mr. Monroe, so as you know, let’s, let’s count on the best outcome. There’s all these scenarios. I could, what could happen, but the best outcome is the war will end and you’ll be able to come back. So given that, let’s see if we could lease this land.”

Monroe found another trusted client of his to lease the land, Gonzalo Mendez. Who agreed to care for the land while Seima is gone.

“So Mr. Monroe goes to Gonzalo and says, Hey, what do you think? Would you consider leasing this farm and everything’s there? You don’t really even have to do much to get started because it’s all there. You lease the whole thing and so he and Felicitas, his wife, decided, Yeah, let’s go for it,” said Munemitsu.

Trusting Mr. Monroe, Tad leased the farm to Gonzalo Mendez just before his family is forced from their home. The Munemitsu family is separated, as Seima, the patriarch of the family, is taken to a high security incarceration camp in Santa Fe New Mexico. Seima’s twin daughters Kaziko and Akiko, who were seven years old at the time, recall the day their father was taken.

“Well, I remember my mom holding my hand because I was home sick with the chicken pox or one of those, I don’t know, whatever. I think chicken pox. But anyway, there’s this man. He’s in a suit. He’s got a hat on, and he’s he doesn’t smile very stern face, you know? And that’s then they took my dad, you know, my mom was crying but, you know, I really didn’t know what was going on,” said Kaziko Munemitsu Doi.

That days is also etched into the mind of her sister.

“I wasn’t I wasn’t home because I was still at school and so when I came home, I was just like I didn’t know what was going on because there were people in the house going through things and stuff…Then after that, I realized that we had to go,” said Aki Munemitsu Nakauchi.

The twins contracted the measles, and while their mother is taken to Poston in Arizona they are sent to a local hospital until they could recover and reunite with their mom in the camp.

“Oh, God, it was so good to see Mom. Oh, I tell you. And I think know, it was it was something that you just you just can’t explain. It’s there when you if when you don’t see your mom for a while and so on, you know, it’s just like kids every it’s like any other kid. You miss your mom, you know? Munemitsu Doi recalled.

Most of what they remember about the camps is the Arizona heat.

“A lot of sand and dusty. Yeah, that’s what I remember. Other than that, it was just the hottest place in the world,” Munemitsu Nakauchi vividly remembered.

“A group got together and we dug underneath the barracks and that was our playhouse, you know, you and you, we had bookcases and, you know, whatever things we could scrounge up or people would give us. And that was where we used to play and, you know, and sing and play games together. But it was so hot that you go underneath that. Sell it. Cool,” said Munemitsu Doi reminiscing about her childhood.

The family spent three years separated from each other. Once Japanese Americans were free to return home, many found that their land was sold, damaged, or stolen. But the Mendez family took care of the Munemitsu’s farmland in their absence, keeping the terms of the lease. However, at this time the Mendez family had to stay in Westminster as they fought a legal battle against the segregation of Mexican American students, known as Mendez v. Westminster.

“My dad and Gonzalo come up with kind of an unusual solution…There’s one farmhouse, one barn and four workers cottages,” said Janice Munemitsu. “So what they end up doing is my dad and grandpa decide we’re going to come back, live in the workers cottage. Gonzalo, you stay and you continue to lease it. So there’s no changes to any of your legal documentation with this case.”

The Munemitsu family worked for daily wages, allowing the Mendez family to stay in the Westminster school district for their court case and still have some profits from the farm. Despite the unusual situation, the Munemitsu family is happy to be home.

“At least we had a place to go back to that was familiar, you know, the old red barn and all, you know, the crop, the asparagus and whatever that was there at the time. Was still there,” Munemitsu Doi said.

The Munemitsu family relied on the kindness of the Mendez family and old friends as the children return to school.

“I was so apprehensive to hear we were away for three years or so… You don’t know what’s going to happen, but this friend from kindergarten Beverley Seelig Rosenow, she was there to greet Akie, and I and to make sure that none of the kids made any kind of derogatory remarks. And to this day, I will always remember her kindness and for her standing up for us,” an appreciative Munemitsu Doi recalled.

Orange County was home to many Japanese American families prior to the war. Around 1,900 Japanese residents were sent to incarceration camps. Most lost their homes, businesses, and farms. Because of this, the Munemitsu family opened up their land to Japanese Incarcerees who had nowhere to go.

“My dad and grandfather invited other Japanese families who didn’t have a place to go. So some of our closest family friends were among those. But now I’m now finding out there were other people who came through, if they needed a place to stay for a couple of weeks before they got their feet on the ground,” Munemitsu said proudly. “If they needed to work and make some money so that they could go rent a place. So it kind of became like this little small village of Japanese incarcerees.”

Once the Mendez family won their case, they moved off the farm, but the two families remain connected because of the impact they had on each other.

The Munemitsu family is grateful for the kindness of strangers during a difficult time.

“I think having friends you could trust, family, friends or neighbors or workers that you could trust made a huge difference. And a lot of times people will ask me when I’m speaking if they’re surprised that I don’t have more resentment or that my parents, my father and my grandfather didn’t have more resentment, said Munemitsu. “And I said, well, I’m sure my dad and grandfather had resentment. It would be not human if you didn’t right. I think how you chose to work through that, how you chose to go forward is what makes the difference.”

EXTENDED AUDIO VERSION:

Support our June Membership Drive and receive member-only benefits. With less than three days left in our fundraising drive, we are running out of time. We are just 57% of our goal of $10,000 in new donations and monthly and annual donation pledges and 48% of our goal of gaining 25 new recurring donors by the end of the month. We need your help during these challenging times. Please help to ensure quality content in amplifying the voices of the AAPI community.

We are published by the non-profit Asian American Media Inc and supported by our readers along with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.