By Dianne Fukami

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

The story of Oakland’s Japantown is unlike many other pre-World War II Japantowns in California. Oakland didn’t have a specific geographical center and instead had pockets of Japanese Americans that were dispersed throughout the East Bay city. World War II and the Nimitz Freeway helped to change all that, so that today, there’s very little evidence that there were thriving Japanese American neighborhoods there at all.

To envision the past, it helps to think of Oakland as having two geographically separate Japantowns in addition to the thriving nursery and floral businesses which for the most part were located in the eastern part of Oakland near the San Leandro border.

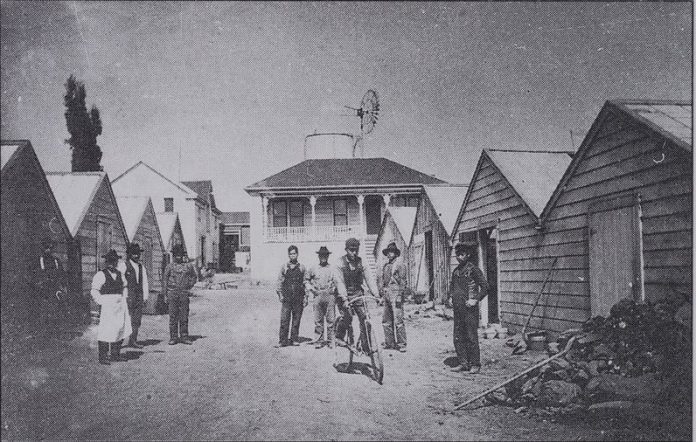

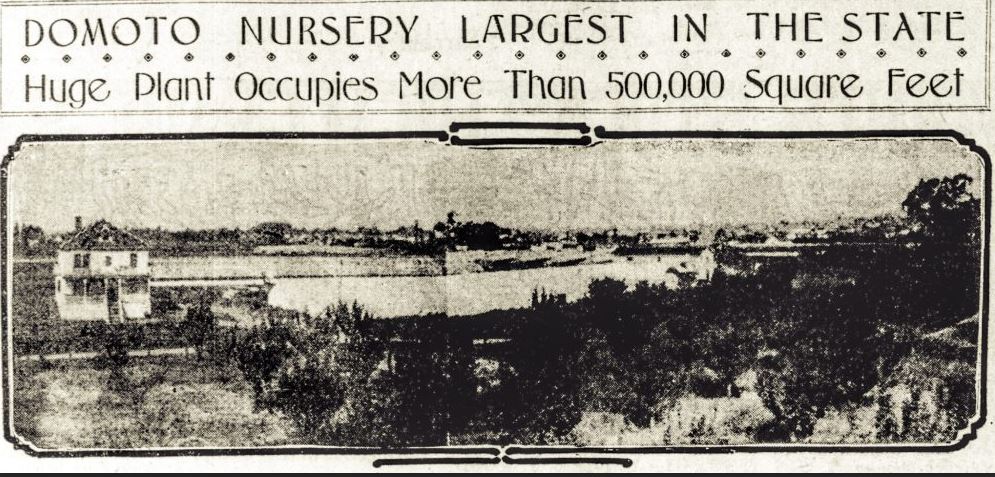

Records show that the first trickle of Japanese immigrants to Oakland began in the 1880s. One of the most prominent families of the time was the Domoto brothers, Kanetaro “Thomas” and Takanoshin, who had immigrated from Wakayama prefecture. They established the first commercial flower growing business in Northern California in 1885 at Third and Grove Streets (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive) streets.

By 1904, now joined by two other brothers, their Oakland business had become the biggest flower-growing enterprise on the West Coast. They were so influential in paving the way for other immigrant Japanese to learn the trade and start their own nurseries in the Bay Area, their nurseries were often referred to as “Domoto College.”

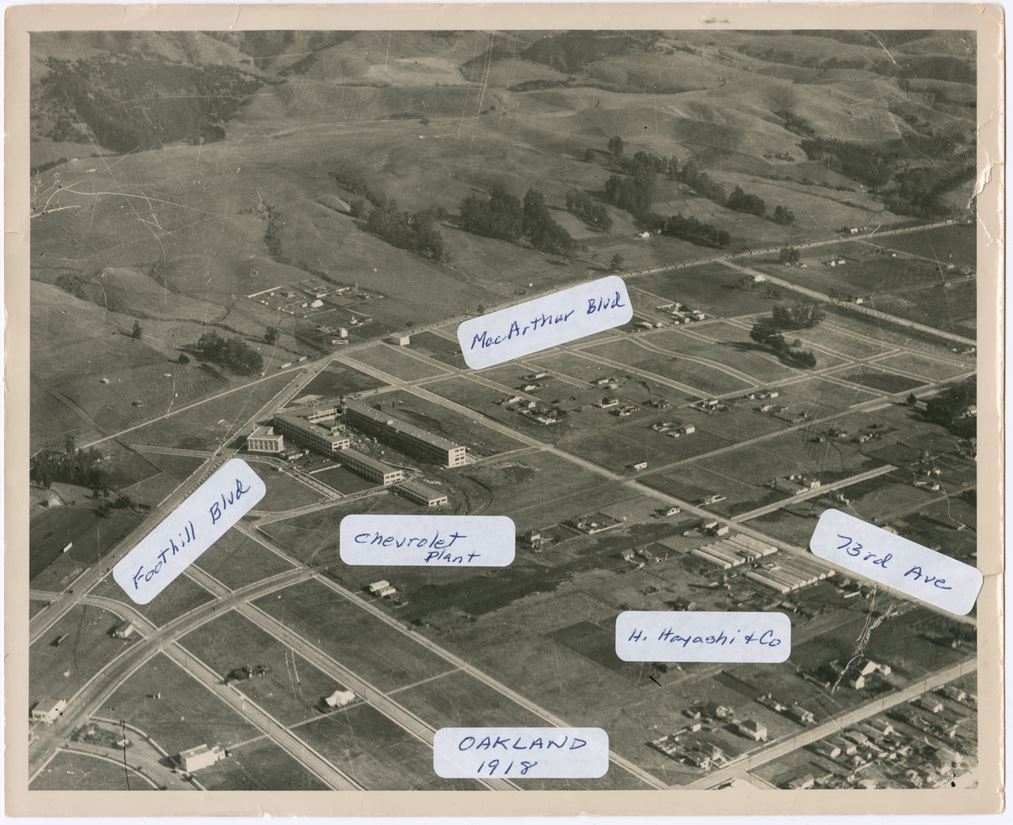

Hirokichi “Harry” Hayashi opened his first floral shop in Alameda, but when he wanted to expand in 1910, he crossed the estuary to Oakland and bought 11 acres on 73 rd Avenue to start his wholesale nursery business. He, like the Domoto brothers, was still able to purchase land before the 1913 California Alien Land Law went into effect that prohibited “people ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural property or possessing long-term leases. (Note: naturalization policies in effect did not allow immigrants from many Asian countries, including Japan, to become citizens until 1952.)

After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, more people including Japanese Americans flooded into Oakland, homeless and now looking for new housing. With more space available in the southern part of Oakland, the Domoto and Hayashi families soon had colleagues in the nursery industry, although post 1913, the Japanese growers could only lease land, not buy it.

Before World War II, there was the Sunnyside Nursery started by the Eisaku Yoshida family in 1915; a different Yoshida family opened the Yoshida Nursery in 1922 on Krause Avenue, which later relocated in the area that would become the Oakland Coliseum, next door to the Korematsu Nursery, owned by the father of famed civil rights activist Fred Korematsu.

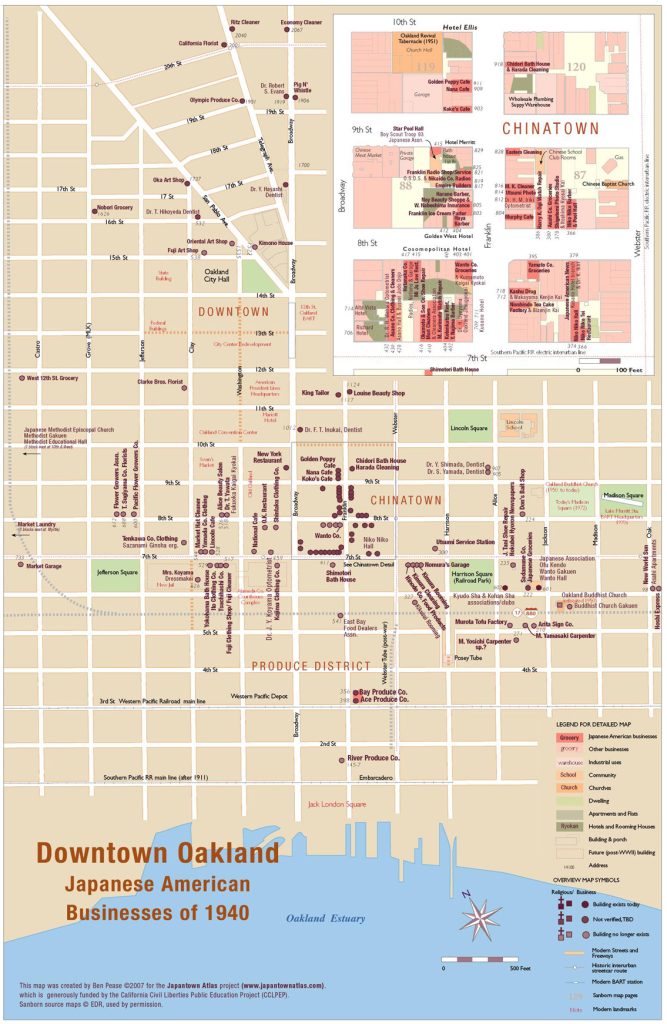

Other notable nursery families include the Shirakis, Nakanos, and Nomuras. In 2007, Ben Pease created maps of the East Bay for the Japantown Atlas Project. Looking at the 1941 Oakland/Alameda map, scrolling down toward the south of Oakland, the names that are labeled in green indicate the locations of Japanese American nurseries as of 1941 before World War II. There appears to be more than twenty. The map indicates other Japanese-run businesses in the area at that time, revealing that the wide distance between the various nurseries and ancillary businesses was not conducive to a “Japantown” in the conventional sense of the term.

Any sense of a pre-war Japantown was located in primarily two other areas of Oakland. One was in the Chinatown area; the other in West Oakland, for the most part between Adeline and Market streets. By 1910, the Japanese American population in Oakland had grown to more than 1500, according to the California Japantowns website.

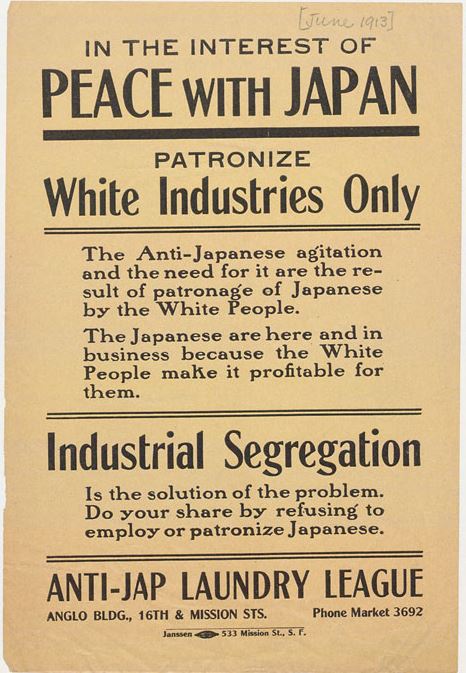

In the first two decades of the 1900s, Japanese immigrants were facing many institutionalized discriminatory policies: anti-Asian racism as part of the fallout from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act; the 1906 San Francisco School Board’s segregation policy targeted at Japanese students; the 1907-1908 Gentlemen’s Agreement between Japan and the U.S. that limited Japanese immigration to the U.S.; and the California Alien Land Law in 1913 mentioned previously. It was not easy to get a job, so in addition to the floral industry, many Japanese turned to the cleaning and laundry business for jobs.

In West Oakland, there were two large laundry businesses of note, Market Laundry, and Contra Costa Laundry. In a 2007 interview with the California Japantowns project, then 92-year-old Oakland native Hiroshi Leo Saito remembered the big Market Street Laundry, operated by partners Y. Kabuki and K. Okada and providing sleeping quarters for employees. In a way, it was a competitor to his own family’s businesses, Saito Shoe Repair and Swan Cleaners, which his immigrant parents operated out of the 3-story Victorian house they purchased on 23rd Avenue before the 1913 Alien Land Law.

Courtesy: California Japantowns

The Contra Costa Laundry, located two blocks away from the Market Laundry, was reportedly a larger facility that also included a dining hall and sleeping facilities for its male and female employees. While both businesses thrived and other Japanese started their own laundry enterprises in the San Francisco Bay Area including Oakland, they became the targets of racism with the emergence of organizations such as the Anti-Japanese Laundry League, founded in 1908 by a laundry union based out of San Francisco. The growing popularity of the Japanese- run laundries were seen as financially threatening and the League’s strategies included picketing the laundries, intimidating customers, preventing the laundries from purchasing equipment, and threatening public officials who refused to advocate for anti-Japanese legislation.

By 1941, according to Ben Pease’s Japantown Atlas Project map, there were more than 20 Japanese-operated cleaning and laundry businesses in Oakland with names such as Togo Laundry, Hoshiaki Cleaning, Hirota Cleaners, and the more American sounding Ritz Cleaners and Sun Cleaning. All thrived before World War II, in spite of efforts to shut them down

West Oakland was a hub of Japanese activity. In addition to the laundries, there were the Ono, Nomura, Kano, Nobori, and Onoda grocery stores, Kinmon Fish Market, and the shoe repair shops operated by the Tanaka, Tanji, and Takahashi families. Jean Shiraki Gize was well-rooted on both sides of the family. Her paternal grandfather had started nurseries in Oakland and Alameda. Her mother’s parents Eizo and Tsuna Nakayama opened a boarding house and opened a grocery store. Jean’s mother would often speak of a neighbor from the old days, Goro Suzuki, later better known as the actor Jack Soo, whose family also had roots in Oakland.

There was also the dressmaking shop and school run by Shizuko Imagire, who according to son Arthur in a 2008 interview with Densho, became the family breadwinner after her husband Sunao became an invalid.

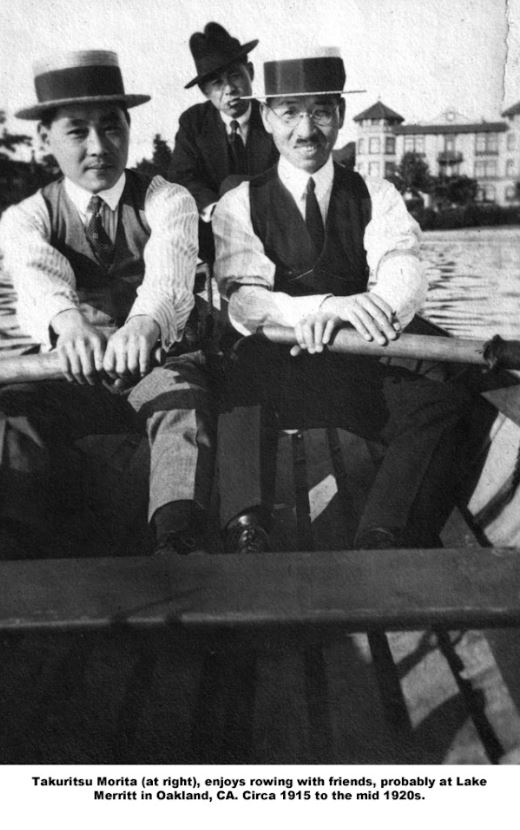

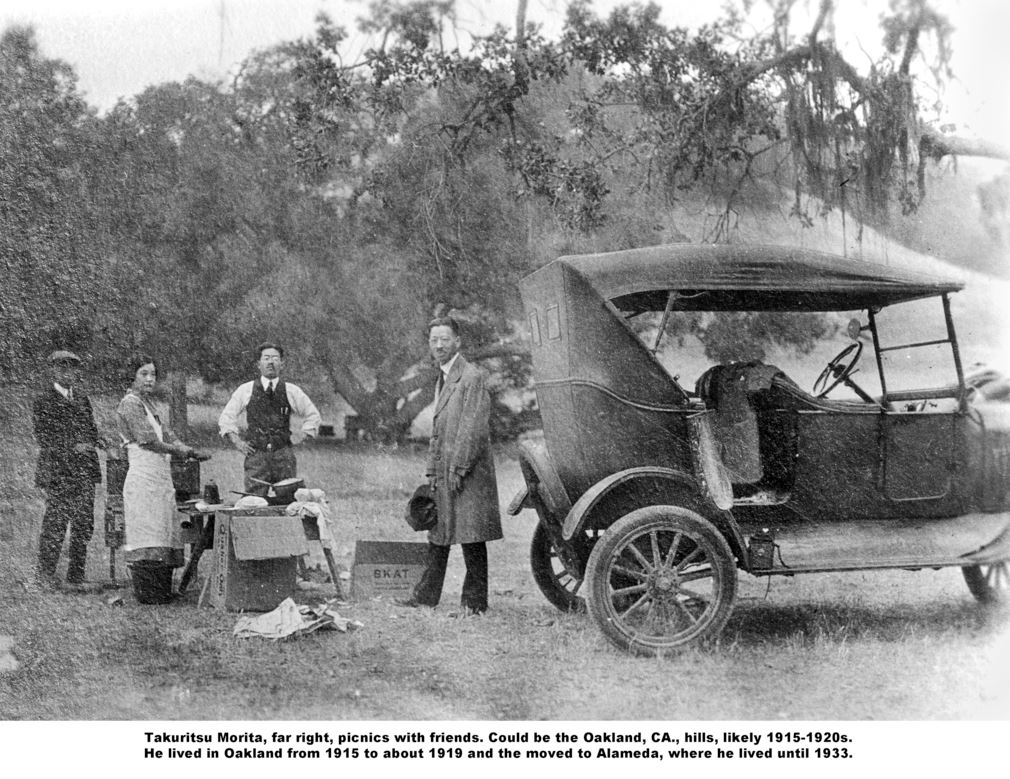

People who were not old enough to get a job viewed pre-war Oakland as one giant backyard. Tomoyuki “Tom” Yokomizo grew up in West Oakland, the youngest of nine children, born in 1934. In an interview with AsAmNews, he talked about his parents and older siblings working hard at their business, Sunset Laundry and his own childhood. He remembered fishing in the estuary for smelt and stripers and even catching fish in Lake Merritt. Like any other American families of the time, the Japanese enjoyed picnicking and leisure activities.

People who were not old enough to get a job viewed pre-war Oakland as one giant backyard. Tomoyuki “Tom” YokoLeo Saito recalled that the West Oakland of his childhood was an integrated neighborhood, made up of immigrant families from Italy and Portugal. At that time, the West Tenth Methodist Church (formerly the Oakland Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church) was a focal point for the community, both within and outside of the West Oakland area. It was established in 1887, and in 1907 a building was purchased at its original location at Tenth and West Streets. As a youngster, Leo Saito recalled that non-Whites were prohibited from public beaches and swimming pools, so when the church moved into a brick-and-mortar home, it became more than a place for religious worship, but also a recreation and community center for the neighborhood. Saito said there were basketball teams, Boy Scout troops, and other sports activities, as well as a Japanese language school, cultural events, and community gatherings. Tomoyuki “Tom” Yokomizo grew up in West Oakland, the youngest of nine children, born in 1934. In an interview with AsAmNews, he talked about his parents and older siblings working hard at their business, Sunset Laundry and his own childhood. He remembered fishing in the estuary for smelt and stripers and even catching fish in Lake Merritt. Like any other American families of the time, the Japanese enjoyed picnicking and leisure activities.

The other Christian church of worship for the Japanese was the Sycamore Congregational Church at 27th and Sycamore Streets, originally known as the Oakland Independent Congregational Church. It was founded to serve the Japanese immigrant community in 1904 and legally recognized as its own entity in 1906. A documented history notes: “families put cardboard soles in their shoes and some women gave up wearing stockings so they might give a little more to the building fund. The Rev. (Shinjiro) Okubo went without his salary, while his wife went to work as a cleaning woman in a Caucasian home.”

The roots of Oakland’s Buddhist church began in a rented house on Seventh Street in 1903, when a group started the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, which evolved to the Buddhist Church of Oakland. After a series of moves, the church purchased land in Oakland’s Chinatown at the corner of Sixth and Jackson streets to build a temple, which was dedicated in 1927 to much fanfare and celebration.

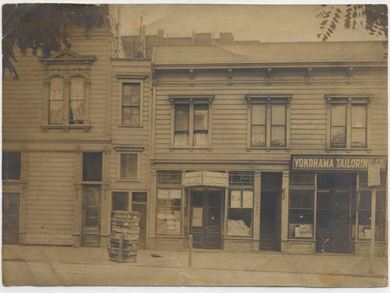

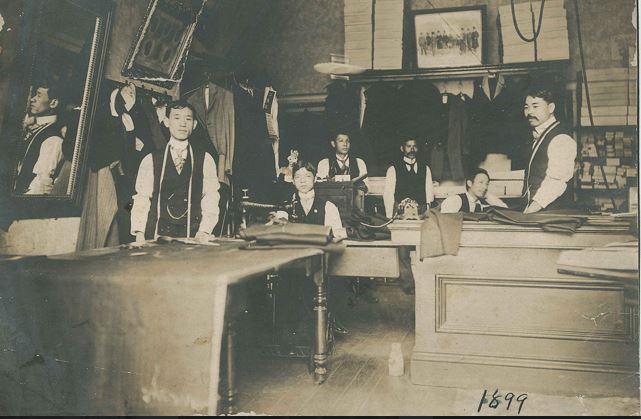

The Chinatown enclave of Japanese families was as robust as those living in West Oakland. Kishiro Yamashita was an early pioneer, immigrating from Naegi via Yokohama in 1897. According to the Yamashita Family Papers (now online courtesy of U.C. Santa Cruz Special Collections), after a stint in New York to learn tailoring, Yamashita settled in Oakland to open the Yokohama Tailor Co. on 513 – 8th Street, where he lived upstairs for a time with his young family. Business-wise, he had correctly determined that no matter what occupation a man held, he would always need a suit for his wedding or funerals. His business was a lucrative one that enabled him to hire employees.

In 1940, Robert “Bob” Utsumi’s family bought the Tsuji Photo on Franklin Street between 8th and 9th Streets, soon renaming it the Utsumi Photo Studio, later joined by the Shigetomi Photo Studio, also acquired by the Utsumis. In his 2008 interview with Densho, Utsumi remembered “…on Franklin Street there was several Japanese businesses. There was a beauty parlor, barber shop, little gas station, pharmacy, and within about three block area there were other stores.” The 2007 map that Ben Pease created for the Japantown Atlas Project shows the documented Japanese American businesses in Oakland Chinatown in 1940 with a more detailed inset.

Records show that in 1940 the Japanese American population in Oakland was 1,800, the fourth largest in California after Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Sacramento. The two segments of Oakland’s Japantown were thriving, a healthy combination of residents, retail, professional services, religious and cultural organizations. But the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7,1941 would be the beginning of the end for this community and would change the lives of not just the Oakland Japanese community but the 120,000 Japanese Americans living along the West Coast

Having felt the pain of racism before World War II, the Japanese community was not prepared for what would be ahead of them. As a young boy before the war, Bob Utsumi remembered accompanying friends to swim at the Forest Pool in Oakland, only to be told upon arrival that “you’re not old enough, Bobby,” and waiting outside for his buddies, only years later realizing his sensitive friend was trying to shield him from the racist whites-only pool policy.

The immigrants had accepted the redlining and restricted covenants that had prevented them from living in nicer neighborhoods, the laws that prohibited them from owning property or having long-term leases, the cry for school segregation, and the anti-Japanese laundry campaigns, but they had never imagined they would be ordered to leave their homes and businesses and be imprisoned for three years thousands of miles away from what had become home.

Nor did they anticipate the hate that would be directed at them or the predatory neighbors eager to swoop down and get bargain prices for prized possessions they could not take with them.

The family who ran the Utsumi Photo Studio lost its primary source of income when the FBI confiscated all cameras and radios shortly after the Pearl Harbor bombing, concerned that Japanese Americans were potential spies ready to contact the Japanese military.

Bob Utsumi also remembered a pool ball crashing through the storefront window during a blackout period.

Tomi Yamashita, now running a cleaning business after her husband Kishiro died and his tailoring business closed, received a threatening letter at her laundry that read: This is a warning. Get out we don’t want you in our beautiful country go where your ancestors came from. Once a Jap always one. Get out.”

(Next week: Part two-Anti-Japanese sentiment reaches a fever pitch in Oakland)

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Donations to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews are tax-deductible. It’s never too late to give.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.