By Raymond Douglas Chong

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo– a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

In the Salinas Valley of California’s Central Coast, 418 Japanese Americans in 1940 lived in the city’s Japantown, mixed with Chinatown and Filipinotown.

Today, the City of Salinas is implementing the Chinatown Revitalization Plan to uplift this lost neighborhood.

Salinas Japantown in the Chinatown District

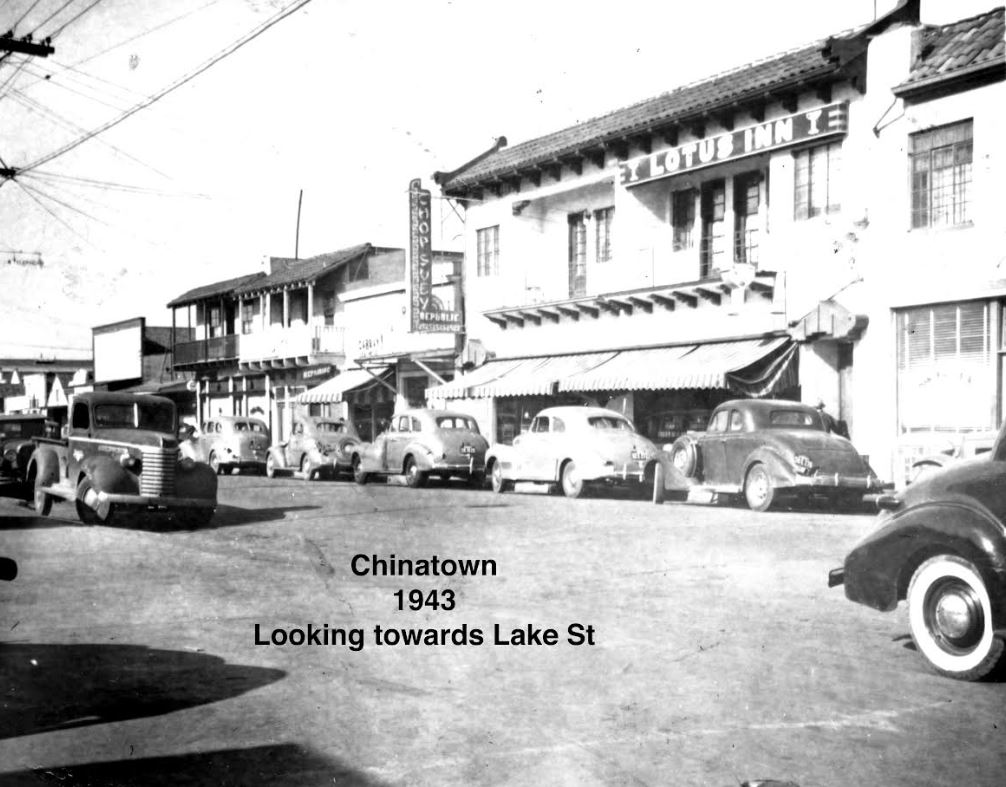

Japantown coexisted with Chinatown and Filipinotown within Chinatown. Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos lived and worked together well in this segregated enclave. The fertile Salina Valley, known as the salad bowl of the world, drove the local economy when waves of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos arrived as farm laborers.

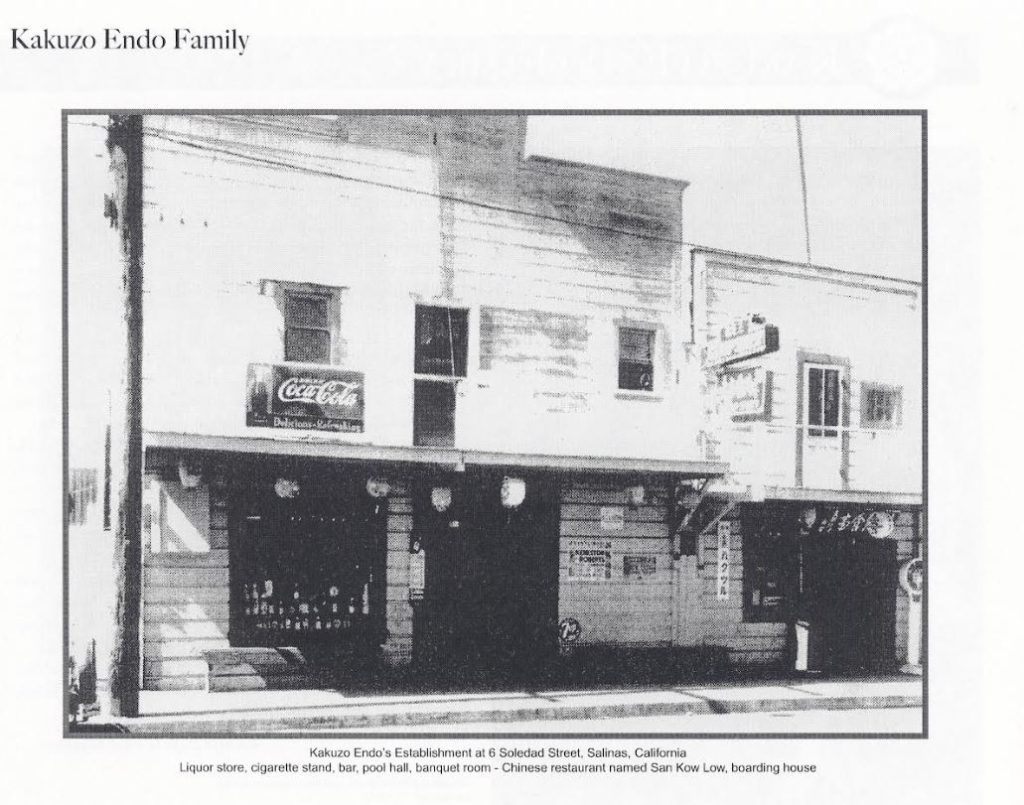

Over 134 Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino businesses and organizations thrived in this Chinatown District. Its hub was centered on Soledad Street near the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks.

Mae Sumiye Sakesegawa diligently researched Salinas’ Japanese American community. Her album covered family stories and photos of the pioneer families. In 2007, Sakesgawa published The Issei of the Salinas Valley – JAPANESE PIONEER FAMILIES. She covered the period from 1881 to 1942.

- 1881 – Issei (first generation) arrived to labor in the sugar beet fields for Spreckels Sugar Company

- 1898 – First boarding house opened. The Japanese Mission Hall was established.

- 1905 – Salinas Japanese Association was organized.

- 1910 – First picture brides arrived. Japanese Hall was built.

- 1924 – Salinas Buddhist Temple was built.

- 1932 – The Salinas chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League was organized.

- 1934 – Bonsho (bell) was installed at the Salinas Buddhist Temple

- 1942 – War Relocation Authority temporarily incarcerated all Japanese at the Salinas detention center and permanently transferred most to Poston concentration in California.

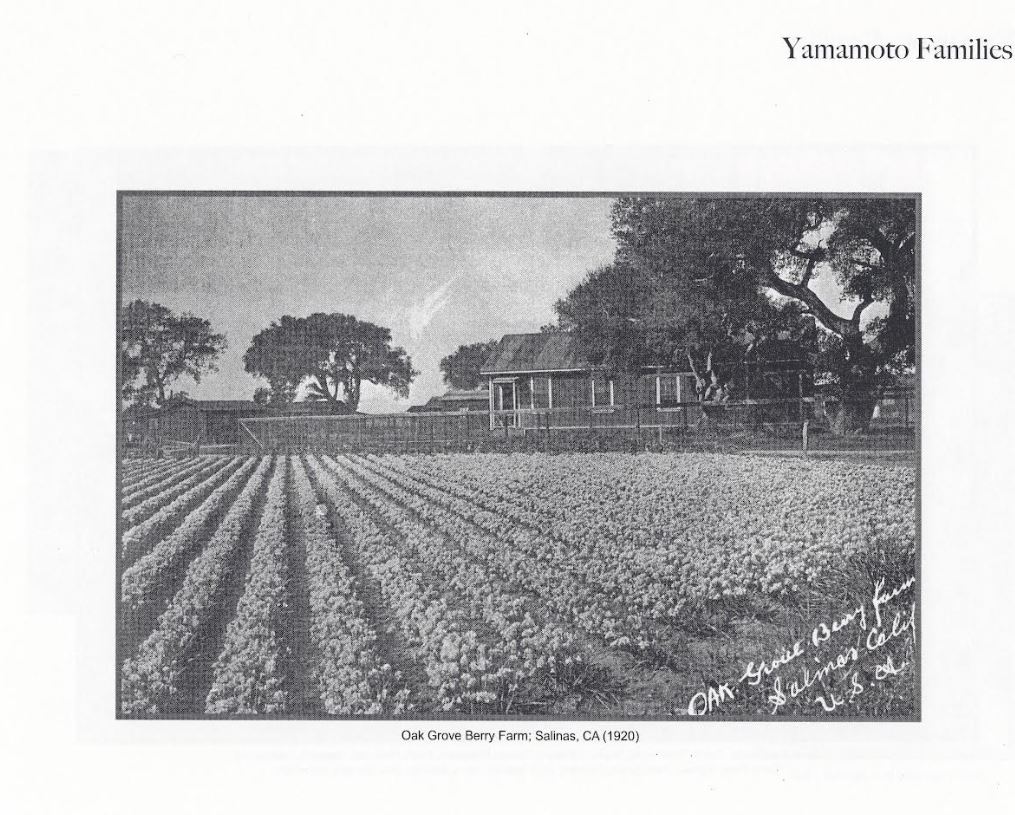

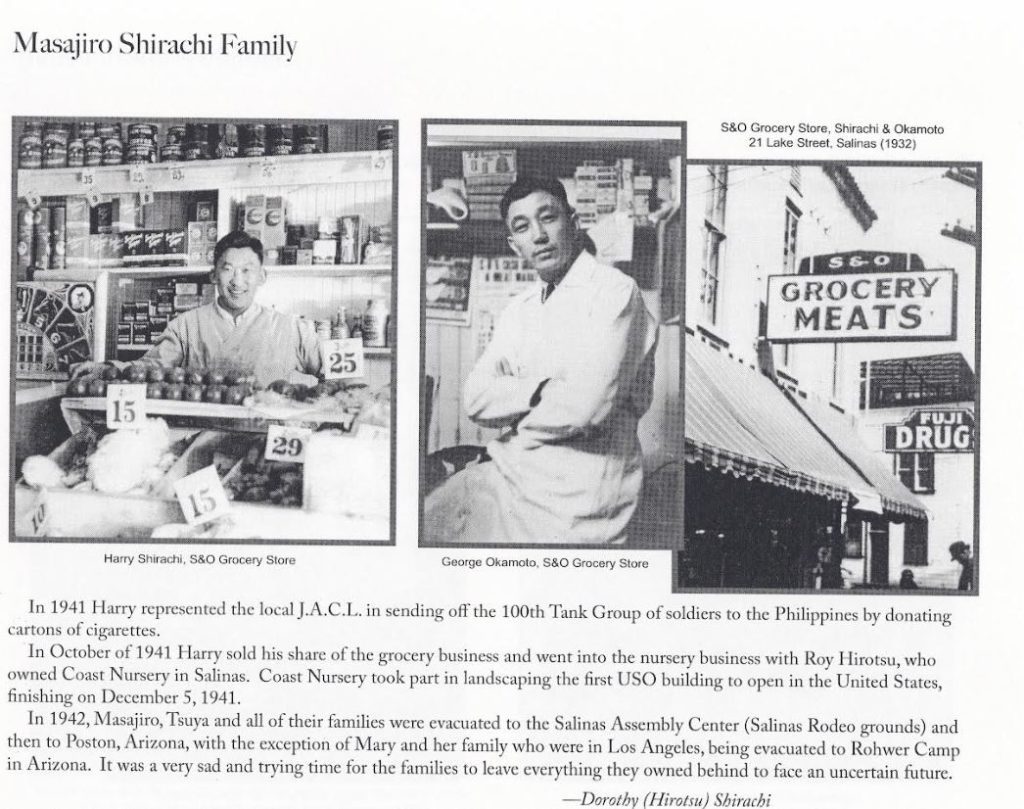

During their heyday, independent Japanese farmers thrived before 1942. They grew celery, strawberries, lettuce, and broccoli in the Salinas Valley. In the Chinatown District, the Japantown merchants successfully sold groceries, merchandise, and services.

In 1930, Wallace Ahyte opened the Republic Hotel and Restaurant on Soledad Street. It was a popular gathering place for the Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino communities. Republic Restaurant served Chop Suey and other Cantonese dishes.

Members of the Asian Cultural Experience of Salinas (ACES) interviewed Sakasegawa (born 1928) about her childhood memories of Chinatown. This is the Cultural Experiences account of that interview:

Mae spent his childhood in Chinatown, mainly on Lake Street. Her father, John Urabe, owned property in Chinatown.

Mae was the oldest, and because her siblings were close in age, she spent much of her time with her grandmother, Taka Urabe. Grandmother Taka knew many Japanese families on Lake Street and took Mae with her on her visits with her friends.

Mae remembered getting senbei from the Aki Toyo store and elderly Japanese men playing Hana, a Japanese card game. Everyone knew each other and was very friendly. There were many businesses on Lake Street, and it also served as a playground for the children in Japantown.

Japanese customs that the immigrants practiced included celebrating Girls’ Day on March 3, with a Girls’ Day Altar, and Boys’ Day on May 5, which also has an altar; but more commonly flew a Carp Banner (koinobori) outside. It was tradition for the number of carp flags to represent the number of boys in the family.

Mochituski (sweet rice cakes) is the pounding of rice and forming of cakes. It was a family and community effort, usually close to New Year’s. The New Year’s celebration was a gathering of immediate family and a time for families to visit and greet the New Year’s with their neighbors. A great feast of food was prepared before New Year, including sushi, raw fish (sashimi), mochi, lotus root, and other foods representing health, prosperity, and good luck.

Mae walked to Lincoln School with other Japanese and Chinese children of Chinatown. She remembers roller skating down Lake Street from Main Street Main Street. Some Japanese boys also made Soap Box Derby wagons to go down the hill. Her grandmother sent her to Japanese Language School at the Buddhist Temple, but she was way behind the rest of the Japanese children because they only spoke English at home.

In another ACES interview, Kaye Kazuyo (Endo) Masatani (born 1929) shared her childhood memories of Chinatown. Again, this is ACES account of that interview:

Kaye remembers living at 6 Soledad Street. At that location, the family businesses included a pool hall, liquor store, and Chinese Restaurant (San Know Low); they also ran a boarding house in addition to living there.

Walking to Lincoln School (seemed like a long way). Though she lived on Soledad Street, her parents did not allow her to associate with the Chinese. Likewise, the Chinese families did not encourage their children to associate with the Japanese. She had a Chinese childhood friend, Helen Lee. After leaving Chinatown, they would walk together and be friends at school on the way to Lincoln School until they returned to Chinatown, when they no longer spoke to each other. Their parents did not want them to associate with Chinese or Japanese.

She went to Japanese School at the Buddhist Temple after school on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. She stopped at Aki Toya Store (Ponton’s Glass current location) to buy senbei (Japanese rice cracker treats) along the way to school.

Since her family had businesses, she was able to take lessons in tap dance and piano. They played with other Japanese children at Central Park or Urabe Park (where the Filipino Center currently is). Kay went to Sunday School at the Buddhist Temple and participated in Obon there. She remembers mochitsuki as a fun and exciting event for her family.

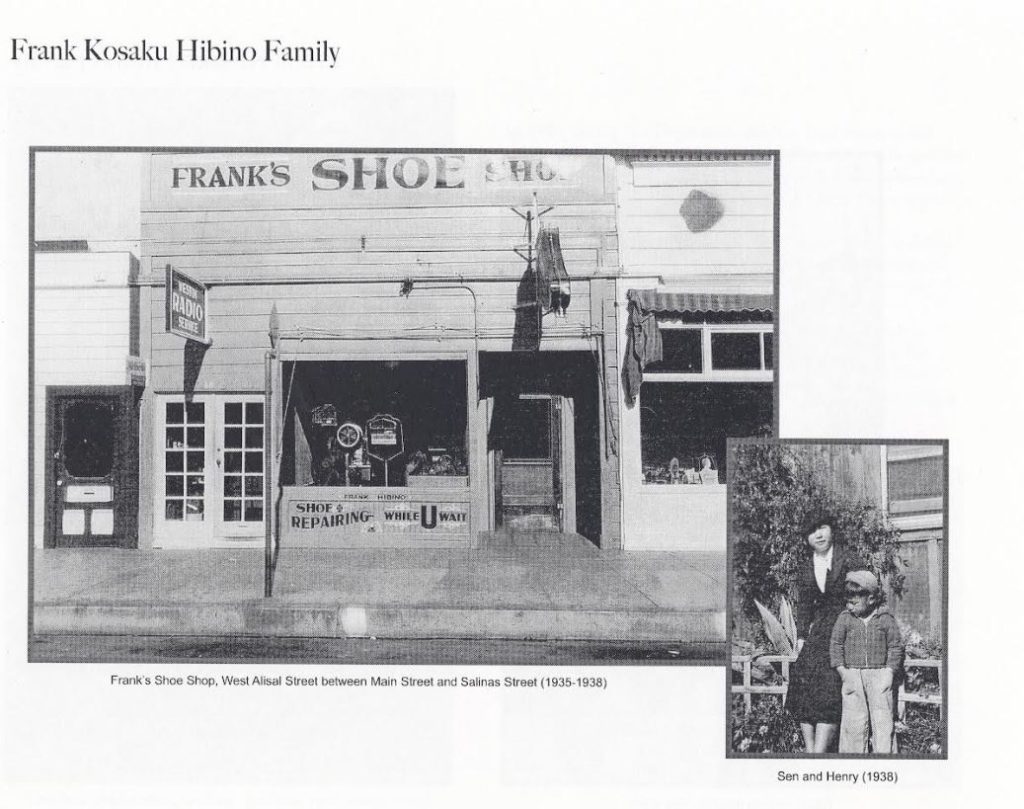

Henry Kazuo Hibino (born 1934), past Mayor of Salinas, remembered Chinatown (CSUMB Oral History & Community Memory Archive. Chinatown Renewal Project; Interviewee: Henry Hibino; Interviewers: Grant Leonard & Carlos Canedo; Date of Interview: October 16, 2010)

Grant Leonard: Alright, well, would you mind going into a little more detail about Chinatown—what it was like at the time, and living in [unclear].

Henry Hibino: Yeah, we’ll see when I lived there—so, I was born in 1934—so, 1946 and ’47 when I was thirteen years old, twelve, thirteen. I was a junior in high school. So, I still remember a little bit, but I don’t remember a lot, you know, things have changed. A lot of the buildings are gone that were there in the old days. But that’s where our—that’s where that two-story rooming house was that my parents owned. It was just right directly across the street from Ted Ponton’s Glass Shop. And Ted Ponton’s Glass Shop used to be Harry’s Garage, and Harry’s Garage moved to another location, where the underpass is there now. They had to demolish that and put the underpass in, and that garage building on the corner of Front and Alisal Street became Harry’s Garage. That originally was Harry’s Garage, and I think the family still owns that, but they rent it to different people.

Carlos Canedo: Do you remember if it was a noisy area or was it really quiet, Chinatown?

Henry Hibino: There was no crime to speak of that I can recall. You know, not like it is today. I mean, I used to—the only way I got to school was we used to have to walk or ride a bike. So, I went from there to Washington Junior High School. We usually walked. [unclear] but we used to walk. I don’t know how far that is, but it’s a pretty good walk. But yeah, Salinas High School was the same way. There was no bus service or anything.

Carlos Canedo: And do you remember what was the game that you played, for example, in Chinatown, with your friends? What kind of things did you do with your friends in Chinatown?

Henry Hibino: Well, there was a park called Snyder Park. It was—it’s right there by the Mexican Catholic churches, right from the backside of that parking lot. I guess it was probably in the parking lot. It was a city owned park that we used to played baseball there all the time. And that’s where we hung out, so to speak. And all the different areas had parks on the corner of Front and Alisal Street where that big housing project is now. That used to be Front Street Park. And there was a lot of those parks all over town. Some of them were on school grounds. Lincoln School was another park—city run park on Lincoln School, and I believe Roosevelt School. But so, depending on which part of town you were from, we used to compete against each other.

Grant Leonard: We’ve heard a lot about the Republic Cafe in Chinatown on Soledad Street. Did you go there often or—

Henry Hibino: We used to go there from time to time. It was considered authentic Chinese food. It was the real thing. One of the dishes that the Republic Cafe was famous for was they had Peking duck, and I know a lot of people will tell you to this day that there is nobody in the whole country that made Peking duck like the Republic Cafe did. It was good. It was good. And I don’t know what they did or how they did it, but anyway, that’s what they were famous for. Republic Cafe was always owned by the Ahtye Family, because I remember they had a gas station across the street, and then the restaurant. So, if you were going into the restaurant, all you had to was leave your car with the gas station, tell them to park. They’d take care of it. And then you went to dinner at the Republic Cafe. They didn’t have any problem like they talk of today. There wasn’t any vandalism or anything really to speak of, even in that part of town.

Grant Leonard: Were there any authentic Japanese restaurants in the area for the community?

Henry Hibino: Postwar, no. Prior to World War II, there was a number of them. In fact, I have—I had an aunt that had a restaurant right down the street from the Republic Cafe. I can’t remember exactly where it was, but then my aunt had a restaurant and my cousin had a candy shop. And we had a lot of his equipment not that many years ago that he had from the candy shop, that we stored out at the ranch. But I think since we’ve thrown it away or whatever. I don’t think any of it is around anymore. But that was just right down—it was right on Soledad Street.

Carlos Canedo: And how did you get along with the other Asian communities [unclear]?

Henry Hibino: How did I get along with whom?

Carlos Canedo: With the other Asian communities in Chinatown?

Henry Hibino: It was never a problem. The Chinese school was always there. The Buddhist church was—they rebuilt that completely, but the old Buddhist church was always there. There were not that many Black families in town. There never was. When I went to high school, I think there was less than six kids, Black kids, going to school in the whole high—Salinas High School.

Carlos Canedo: But did you have, like, Chinese friends and Filipino friends?

Henry Hibino: Well, we had, as I recall, the guys that I hung out with and we stuck together even to this day. One kid was—kid, he’s not a kid anymore. He’s Mexican. We had a Filipino and myself, and I guess there wasn’t any Chinese guys that hung around with us, but then we had a number of Caucasian kids. But race never was an issue. Never was.

Carlos Canedo: And in Chinatown, do you remember, like, I don’t know, some festivals that they did in that time?

Henry Hibino: The what now?

Carlos Canedo: Some festivals, like, festivities.

Henry Hibino: The festivities—the Buddhist church always had—has that Obon they call it in July. They’ve had that for, I don’t, forever. And they still have it to this day. And that’s—I’m not Buddhist, so I’m not familiar with all that. I’m kind of an outsider, but that’s a big activity for their church. I think it happens in July every year.

Grant Leonard: And were there other celebrations, the Chinese New Year, that affect the community—in San Francisco?

Henry Hibino: There was not that much festivity in Salinas as far as Chinese New Year’s go. The Chinese people that were here, they went to San Francisco for the big festivities. I don’t know how much of a celebration they had in Salinas. If they did, I’m not really that familiar with it. Our neighbor is a Chinese dentist, and he’s active with the Chinese people today, but they—I think they probably have a party or anything, but there’s no big, big festivity here.

Carlos Canedo: Do you remember, like, if there was a market or where they sell fresh fruits or—

Henry Hibino: Oh yeah, there was a lot of Japanese grocery stores, a lot of Chinese grocery stores, a lot of Filipino markets, and the same way with the restaurants. There’s a book that a lady just put together, came out, on the history of the Japanese people in Salinas. And, you know, it tells you what stores were in town and this and that and—I don’t know where my wife put it. But anyway, yeah, it’s the history of the Japanese people. And somebody’s doing the history of the Chinese people, and I’m not sure if somebody’s doing the Filipino People, but the Japanese one is done, and they’ve been selling it. It’s kind of interesting. We have one here around the house.

Incarceration – Salinas Detention Center and Poston Concentration Camp

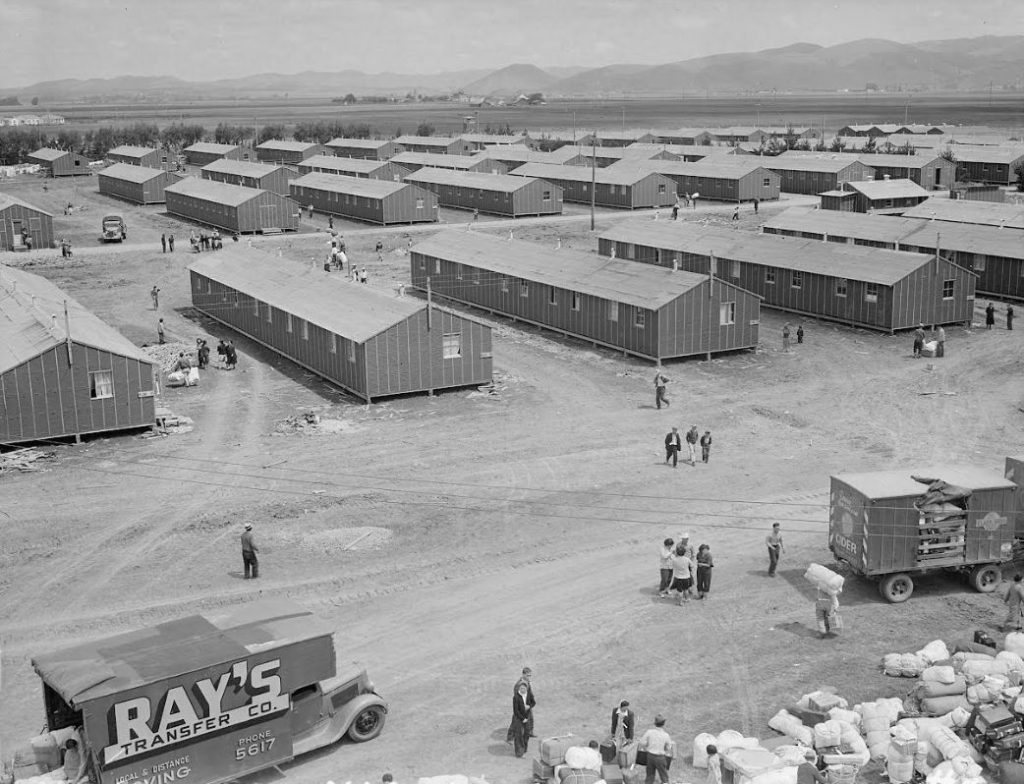

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) detained the Issei and Nisei (April 27 to July 4, 1942) at the Salinas detention center, the Racetrack and Fair Grounds.

Salinas Temporary Detention Center marker is inscribed:

This monument is dedicated to the 3,586 Monterey Bay Area residents of Japanese ancestry, most of whom were American citizens, temporarily confined in the Salinas Rodeo Grounds during World War II from April to July 1942. They were detained without charges, trial, or establishment of guilt before being incarcerated in permanent camps, mainly at Poston, Arizona. May such injustice and humiliation never recur.

The WRA transferred them to Poston concentration camp in southwestern Arizona on the Colorado River Reservation in Yuma County in the Sonoran Desert, the Colorado River. The prisoners faced hot and humid summers and cold winter nights in the barren and desolate land. They experienced high winds and dust storms. They were imprisoned until November 28, 1945.

Resettlement

By November 1945, Japanese Americans resettled in Salinas. However, the White community opposed and resisted their resettlement.

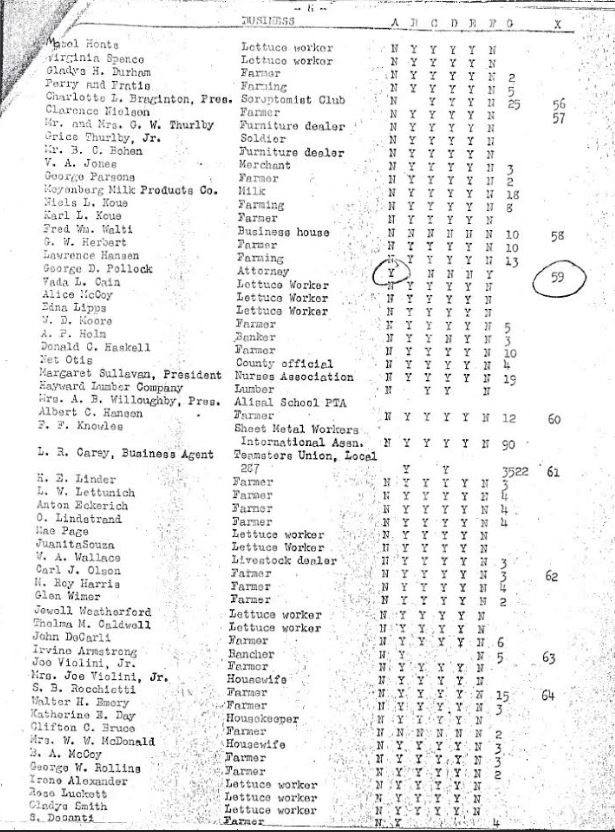

In 1943, the Salinas Chamber of Commerce surveyed more than 750 residents through the “Survey of Attitudes of Salinas Citizens Toward Japanese Americans During World War II. They asked seven questions in the questionnaire.

The first question was “Do you believe it desirable that Japanese who are considered loyal to the United States be permitted to return to Pacific Coast states during the war?” The 750 residents nearly unanimously answered: No.” George Pollock, an attorney, was the lone dissenter in answering “Yes” in defending the Japanese. He believed in progressive causes.

Larry Oda, past National JACL President, commented on the resettlement. “The Monterey Welcome: Return of the Japanese American Incarcerees.” (Gaffney, Amanda; Rota, Christian; and Khalsa, Sat Kartar, “The Monterey Welcome (Episode 9)” (2021). OtterPod).

Larry Oda: Salinas was known as the Salad Bowl of the World. For the amount of lettuce and other green vegetables that were grown there. And the fact is that, over half of the crop was grown by Japanese farmers, who only had, I think 40% of the land. So, they were very productive and the other farmers in the Salinas Valley saw that, you know, here all the vegetables were coming out of these little farms. Their farms were much larger, but they couldn’t produce that number of crop, I guess. So, in my mind they were jealous. And they thought that, well, you know if we can get that land, we can be the ones growing the most crops. They saw the opportunity to seize that land, you know, when the Japanese were taken away.

Masatani remembered:

Returning to Salinas after the War, her family businesses before the war were rented property.

So, with no place to stay, she became a House Girl. Like a nanny, she cooked, cleaned, and cared for the family’s children. She was also attending Salinas High at the time. She felt discrimination at the time and only had six to seven Asian girls who would associate with her (which included Filipinas). But she graduated and later completed business school.

The family of the house she stayed at had friends who would often visit. Those friends were a family that was affected by the Bataan Death March. When this family visited, she was told to hide in the back room and not come out. Despite discrimination, Kaye said that living with the White family was a good experience because it showed her a lifestyle that she never would have been exposed to.

Hibino described the postwar community in Salinas.

Grant Leonard: You mentioned about the difference between prewar and postwar for the community.

Henry Hibino: Well, Salinas had a very large Japanese community in Salinas. Most Japanese people were involved in agriculture, and so they were either farm laborers who later became farmers or sharecroppers, or some of them became big shippers, lettuce shippers, and some of them became big farmers. They were big farmers. And so, when the war took them all away, a lot of—other than the people that owned property—didn’t come back. So, post-World War II, the Japanese community was very small. And then after World War II, a lot of those flower growers came to the valley. There’s a lot of nurseries in town now. And most of them came from Japan under some refugee act, that they were able to come to this country. And so, they—there is a large community of them. But they’ve been on hard times too. The flower business is tough business with the imports. Can’t compete with the imports. But the ones that are surviving I think have done well.

Susumu Ikeda remembered the resettlement. (CSUMB Oral History & Community Memory Archive, Chinatown Renewal Project; Interviewee: Susumu Ikeda; Interviewer: Kristofer Owens and Sean Poudrier; Date of Interview: November 14, 2010).

Kristofer Owens: Wow. Can you tell us about life after the internment camp?

Susumu Ikeda: Yeah, after the war was over [unclear]—yeah, I guess when the war—and then the government said that they’re gonna close the camps by the end of the year, at the end of 1945. So, we had to go find a place to go to. And I was born and raised in Salinas, so we couldn’t go back to Salinas, because my dad didn’t own property there, and Salinas had a tank company that was in the Philippines. And they were captured by the Japanese, and they were kind of mistreated, so the feelings were very high against the Japanese, so it just didn’t feel comfortable going back to Salinas. So, we came to San Jose.

Kristofer Owens Okay.

Susumu Ikeda: Uh huh. And when we came here, you know, housing was very scarce, so the Buddhist church here opened up their hall, and they had a whole bunch of cot beds there, for the men folks to sleep in the church there. And then there’s another building on site. All the women folks slept there, and they had a kitchen there, so we ate there. And I guess we must have stayed there about, oh, two months until we found housing. Then we left that place to our new home. But so, being that jobs, good jobs, were scarce—a lot of jobs were available, you know, picking fruits and things, so that what we did. So, we as a family, as a family during the summer, we used to go pick apricots and pears. And then early in the spring, my dad and I, we’d go pick cherries. And we all worked out on the farm as a family—

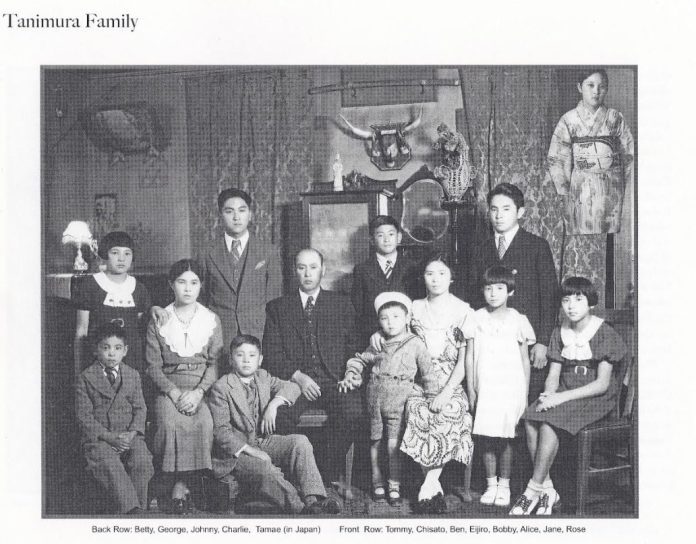

After their resettlement from the Poston concentration camp, the Tanimura family rebuilt their lives by growing produce in the Salinas Valley again. Expanding their farmland, they grew iceberg lettuce, celery, green onions, sweet anise, and endive.

On November 10, 1982, Tanimura & Antle, a family farming business, was officially established. Today, Tanimura & Antle farms thousands of acres of soil and ships premium fresh produce throughout North America, Europe, and Asia.

In Though I be crushed: The wartime experience of a Buddhist minister, (1985), Reverend Bunyu Fujimura described his life in America. In 1935, he served at Salinas Buddhist Temple, where he was responsible for Japanese language schools. IN 1940, he became head minister.

Fujimura was arrested in February 1942. He was interrogated and imprisoned in Salinas and San Francisco. Then, he was eventually imprisoned in the Poston concentration camp.

After his forced stay in Chicago, he returned to the Salinas Buddhist Temple in 1946, serving until 1957.

Today, the Buddhist Temple of Salinas continues to promote Buddhism in the Salinas Valley. Since 1960, they have hosted the annual Obon Festival. They celebrated its 100th anniversary in October 2024.

Asian Cultural Experience of Salinas and the Republic Café

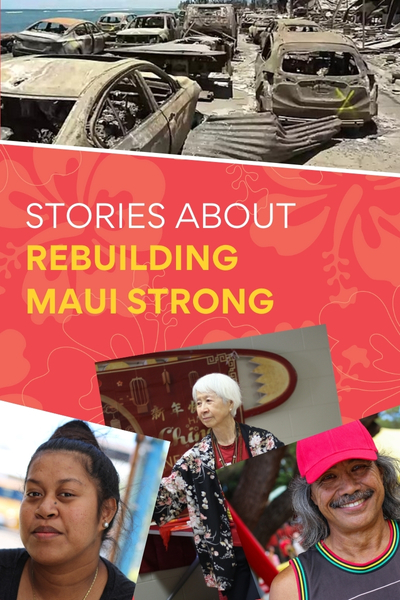

Since 2008, ACES has endeavored “to preserve, promote, and enrich the history and multicultural identity of Salinas Chinatown, historically the home of the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino communities of Salinas.”

ACES collaborated with California State University, Monterey Bay, the Chinatown Renewal oral histories from 2007 to 2014. They published Our Salinas Chinatown (2023), a collection of short essays, interviews, and art by people living and working in Salinas Chinatown. ACES sponsors the annual Asian Festival in the Chinatown District. It showcases the cultures of the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino communities.

ACES’s primary goal is to renovate the historic Republic Café in Chinatown into an Asian cultural center and museum.

In 1941, Wallace Ahyte and Bow Chin built the Republic Café on Soledad Street. It was a major gathering place for Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos until 1988. The building is listed in the National Register of Historic Places (2011). The property is significant as a long-time gathering place in Salinas’s Chinatown for the area’s Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino communities.

Close

From 1881 to 1942, the Japanese Americans flourished in the lost Salinas Japantown of the Chinatown District in the heart of the agricultural Salinas Valley. They thrived as farmers and merchants among the Chinese and Filipino communities. The Asian Cultural Experience of Salinas champions the past glory of the Chinatown District with its Japantown, including the historic Republic Cafe and its iconic CHOP SUEY neon sign.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Asian Cultural Experience is renovating the historic Republic Café.

Dear Raymond

My name is Lynn Sakasegawa, and I’m Mae’s daughter. I love your article and wanted to let you know that we have published a new second edition of The Issei of the Salinas Valley: Japanese Pioneer Families, with more information and additional pictures. The book is available for purchase at http://www.JapanesePioneers.com. Thanks to the generosity of the Tanimura Family, we received a grant and are able to send free copies to cultural institutions and libraries. Thank you for remembering my mother’s contribution to this history. I’m working to continue her legacy with this new edition.

Very nice presentation of Salinas Japanese before the WWII, in the 50’s I had attended Hartnell College but Salinas community was very little that I could remember, spent some time with Hank Hibino and Bill Oka in camp 2 concentration camp Poston Arizona.