By Aviral Gokool

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo– a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

With its waves gently washing over the soft, beige shoreline, and the pristine yet mildly salty breeze flowing throughout the land, Santa Monica has been a destination for tourists to visit and locals to live in. Over the weekends, families enjoy Santa Monica Pier’s carnival rides, booths and funnel cakes while Ocean Front Walk is filled with a younger crowd skating, biking, or jogging down its path.

Before Santa Monica became a location tourists and locals flock to, businessmen fought over who could develop the next part of Santa Monica Pier. Railroads were quickly emerging across the US, and immigrants began flooding into the US. Though amongst the chaos in the late 1800s, Santa Monica’s beaches remained just as beautiful.

But Hatsuji Sano, an Issei (Japanese immigrant), saw more than Santa Monica’s beautiful environs, tranquil waters, and bustling life; he envisioned a wealthy fishing port.

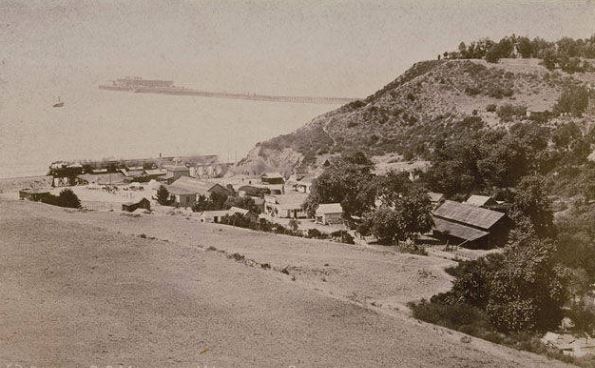

Upon arriving in the Santa Monica area, Sano found a prime fishing spot with an unused wharf that stretched about 4,500 feet into the ocean. This monstrous wharf was a remnant of the Free Harbor Fight in the 1880s where Collis Huntington tried to establish the LA port in Santa Monica where he ultimately failed, leading to an abandoned wharf frequently used by smugglers.

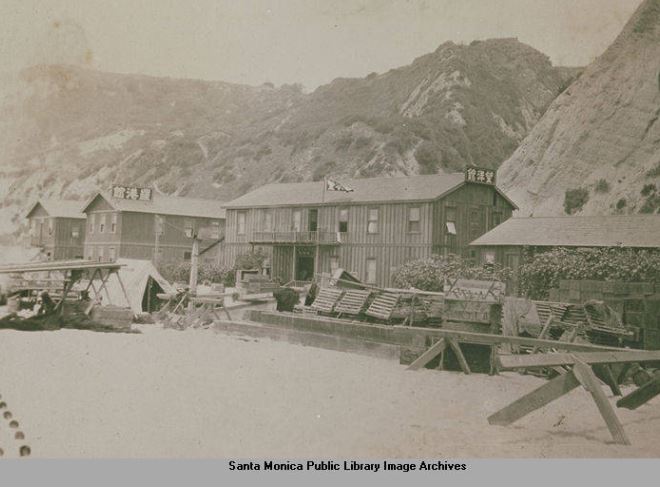

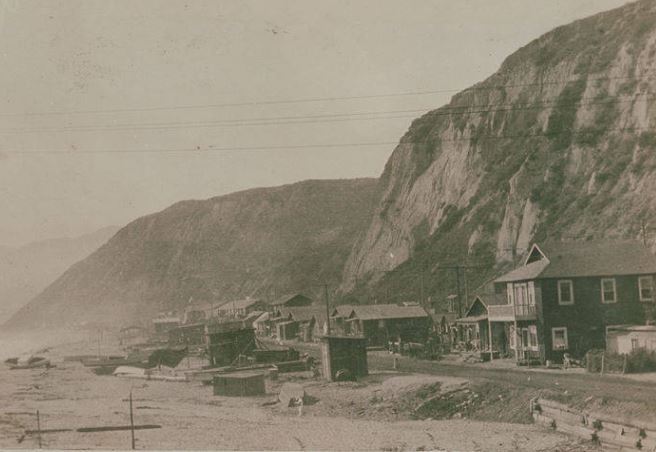

With the bountiful fishing resources and the port’s oceanic advantages, Sano saw an opportunity for economic profit and prosperous trade. As such, he and a handful of other Issei that migrated from Hawai’i, Oregon, and Northern California built houses along Temescal Canyon’s coastline, right next to the wharf. Thus began the start of the fishing village, Maikura.

“By around 1910, there were maybe 50 people there. Two-thirds Japanese and one-third Russian… Lots of people from Santa Monica and LA would take day trips there to go fishing on the pier.” Nina Fresco, a researcher who serves on the board of Santa Monica Conservancy and is authoring a historical book on Santa Monica, told AsAmNews.

Throughout the years, the small fishing village slowly expanded to harbor almost 300 people along the narrow coastline. Japanese men brought mail-order brides from Japan and families from Japan soon moved into the village. Hotels, restaurants, and locally-owned businesses appeared in bunches as the village developed into a proper town.

With an expanded community, proper roads were paved, power cords ran along walking paths just behind large study wooden houses, and gas lines were installed in every building. Most things were constructed by the fishing community themselves.

“There would be huge storms and tons of damage would happen,” Fresco told AsAmNews. “People would run through the hills, their buildings would be damaged or destroyed and they would just rebuild. They were from Japan, they were used to earthquakes, floods, and tsunamis. So they took it in stride, they were badass.”

Like Sano envisioned when he first arrived in Santa Monica, a prosperous fishing village was successfully established. Business within the community was bustling with day travelers, casual fishermen, and families that visited over the weekends.

Since the village had easy access to cultural hubs like Little Tokyo and Sawtelle, people from the village frequented those areas to attend Buddhist Churches, social gatherings, sports, and other community based activities.

Issei fishermen also sold a majority of their catch to the Japanese community in the LA and Santa Monica areas where seafood demand was largely concentrated, eventually opening seafood related businesses and stores in those locations as well.

“[The fishermen] were very successful,” Fresco told AsAmNews. “These were not poor, miserable, struggling people. They lived a simple life and they didn’t need fluff. They were all about the fishing.”

Maikura grew to be reminiscent of a mini Terminal Island. The community was tightly knit and independent. Residents on the island also welcomed tourists, outside families, and even renamed their port after George Freeth, the person who revitalized California’s surfing scene, introduced the notion of lifeguards, and saved four Japanese men from drowning in a storm.

Sano and the villagers managed well on their own without much government aid and support since its establishment in 1899.

However, in the early 1900s, Santa Monica’s land was annexed to Los Angeles County. Effectively, Maikura belonged to LA county and their land was controlled by a developer named Robert Gillis who owned the Santa Monica Land and Water Company at the time.

Gillis sought to develop an affluent caucasian neighborhood in the Pacific Palisades just above where Maikura was located. But with the Issei and Maikura in the way of his plans, he needed an excuse to recolonize the area.

“[Gillis] has a huge resume of evil, racist acts,” Fresco told AsAmNews. “His excuse was that there wasn’t a proper sewage disposal system in the fishing village and it was unsanitary. It was too expensive to install so they had to clear them out.”

“We know that those fishermen had just rebuilt the village and were doing very well,” Fresco told AsAmNews. “They could easily have installed the sewer system by themselves to the city of LA or the Southern Pacific Railroad or Mr. Gillis. It was just an excuse… They basically scrapped the site and turned it into a beach for white people.”

Residents of Maikura had no power to counteract Gillis’s demand so by 1916, the village was destroyed, the wharf dismantled, and villagers dispersed to other Japanese enclaves in the LA area.

Those who sought to keep their fishing practices moved to Terminal Island while the few that remained managed to buy sizable homes in Santa Monica. People who moved to Santa Monica proper mainly transitioned into gardening and farming professions as truck farmers.

“Between 1910 and 1920, even though they couldn’t own the land, the Japanese were so successful and productive with their truck farms, they basically provided 90% of the produce in California. It kind of stayed that way until when incarceration happened in the 1940s; it was a huge crisis,” Fresco told AsAmNews.

A small handful of seven or eight Japanese families also managed gambling concessions fronted as gaming booths on Ocean Park Pier, now known as Santa Monica Pier. Since gambling was illegal, the games were based on skill rather than luck but naturally, the house always won in the end. These families generally saw great financial success throughout the years especially in 1933 during the height of the Great Depression where people were desperate to win money in any way they could.

People gambled away too much money and became impoverished, forcing LA County to ban gaming parlors. This marked the end of the Japanese businesses on the pier, but with their financial success, families found homes and communities scattered around Santa Monica.

Compared to neighboring areas like Terminal Island, Sawtelle, and Little Tokyo, Santa Monica’s Nihonmachi (Japantown) was quite small. There were about 50 Japanese single males living in Santa Monica in 1910 and by 1920, Japanese immigration marginally increased with Los Angeles County seeing upwards of 11,000 Japanese migrants. This number could allude to how many Issei males brought their wives from Japan after settling and obtaining stable income. By 1930, Santa Monica totaled 432 Japanese residents.

Most Issei-ran buildings in the Santa Monica area catered to the Caucasian community and alongside the numerous nurseries and florists, also had food stands in Caucasian markets and operated chop suey restaurants which were popular amongst white Americans.

However, at the heart of Santa Monica’s Japanese community, there was a Japanese association on 16th Street where local business owners and residents gathered for events, parties, and meetings while Japanese schools that taught language and customs were held for young Nisei (second generation American-born Japanese) children. There was even a Free Methodist Church 12th Street where Japanese residents from Santa Monica and Venice gathered to celebrate mass.

Although, Santa Monica Issei and Nisei frequented the neighboring Sawtelle’s bustling Japantown since they city had a larger, more condensed, and pre-established community that often had Kenjinkais (prefectural associations), billiard halls, bath houses, and Japanese films.

Meanwhile, Little Tokyo in the heart of Los Angeles was the main hub for all Japanese enclaves in LA County. Santa Monica Japanese residents typically attended Little Tokyo’s Buddhist temple and celebrated traditional festivals like Obon.

Santa Monica had a harmonious blend. It was rich in Japanese shops, culture, and affluent families. The city was in the middle of three larger hubs while cultivating their own small circle. For the most part, families in Santa Monica lived a very comfortable and peaceful life. But their lives were forever traumatized after Executive Order 9066 was issued.

Families were given only a couple days to pack their belongings in one or two suitcases. People sold off their property and stores at cut rate prices as landowners and conniving businessmen took advantage of the dire situation. Heirlooms, cultural items, and anything related to residents being Japanese were buried, destroyed, or tossed out. In just a few nights, any trace of being Japanese was eradicated and shamed. The government found it was time to destroy the deeply rooted communities and their spirits.

Families from Santa Monica were sent off to Manzanar. At these concentration camps, families dealt with poor food, little privacy, and terrible housing conditions. Winters were brutally cold while summers were unbearably hot. Most of all, people were terrified. They were imprisoned for honoring their culture. For not assimilating well enough into American society. For simply being Japanese.

Manzanar and the other camps attempted to destroy the Issei and Nisei’s spirits and in a way, eradicate their Japanese heritage. For a time, the U.S. government was successful in their attempts.

After being held at these camps for nearly four years, it was difficult for Issei and Nisei to talk about their traumatic camp experiences. Most Japantowns were never revitalized because residents were scared they would be punished again for condensing and celebrating their culture. The community scattered around, it was harder for the government to catch them all if they weren’t in one place. After the frenzy of Order 9066, businesses were never returned, assets were frozen, and houses were scarce.

People either returned to Japan, moved to the East Coast, or tried to reintegrate in their former neighborhoods. Many Santa Monica families were fortunate to be able to have bought their homes or have someone look after their property and storefronts. Others moved to the east coast for a short while before returning to Santa Monica.

In some cases, people lost their loved ones during the incarceration period, pressuring widows or single fathers to work several low-wage jobs and live in dilapidated apartments. In Santa Monica, the Free Methodist Church was turned into a rooming house because of the post-war housing shortage.

The resettlement period depended on how lucky each individual was and if they had friends that aided them before, during, and after the incarceration period.

“Eventually the community built up again,” Fresco told AsAmNews. “More local people from the region and maybe a third more people who were from the evacuation area decided to come to Santa Monica… It wasn’t until the 1950s that they started thinking about community again.”

Once people were able to buy their own houses and gain some solid footing in Santa Monica, the older generation wanted a community center to hold events and gather from time to time. A group of Issei leaders formed the Santa Monica Nikkei Hall, Inc. in 1951. For six years, they saved and pooled their money, eventually purchasing property at 1413 Michigan Avenue. The Nikkei Hall was fully constructed in 1957.

For nearly 60 years the Nikkei Hall served as the central hub for Santa Monica’s Issei and Nisei. Generations of families reconnected with their culture, celebrated holidays, held gatherings, and conducted funerals and support services. But the Nikkei Hall was more than just a community center. It was a means for people to be proud of their heritage, celebrate being Japanese, and rebuild their spirits that were tarnished by the camps.

As the years went by, families dispersed to other areas of the US or the world. The future generations of Japanese-Americans pursued professions outside of gardening and fishing. As such, Santa Monica’s Japanese-American community gradually dwindled to just a handful of members by 2017.

The remaining members of the hall sold the property to a low-income nonprofit organization called EAH Housing. Proceeds were donated to local community and religious organizations who have been entrusted to preserve and maintain the Ireito, memorial tower, in Santa Monica’s Woodlawn Cemetery. The memorial honors Issei who settled in Southern California’s bay cities as well as the generations of Japanese Americans including those who served in the U.S. military.

On Oct. 2, 2024, the Laurel opened its doors for individuals earning between 30% and 50% of the area median income and provides housing for those who are or at risk of being unhoused in Santa Monica. Just in front of the complex sits a beautifully restored and preserved Nikkei Hall.

A plaque describing the history and story of the Nikkei Hall is placed on the exterior of the pristine, white building as a small, newly restored Japanese garden decorates the immediate surroundings. The hall will continue to serve as a gathering place for the apartment’s community members and facilitate resident services.

The Nikkei Hall received the exact love, care, and attention it was always showered with by its former owners. Though new and ravishing on the outside, its purpose will remain the same for many years to come: to serve the Santa Monica community and provide relief for those in need. The spirits of the Issei and Nisei community will continue to persevere and remain strong for many years to come.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

Happy Lunar New Year. We’re almost there. We are now 68% of our goal of meeting our $5,000 matching grant challenge with less than 7 full days to go. Every donation will be matched dollar for dollar through Sunday for up to $5,000. All donations will go toward fully funding an editor position at AsAmNews and to support our reporting. You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.