By Aviraj Gokool

A small 6-year-old boy stares out the window. Red police lights flash the corner of his eye every few seconds. The rattling of bags, concerned Japanese chatter, and police sirens keep him awake on the small transport bus. Worry, anxiety, and uncertainty looms over the adults, but the boy sits in silence as the convoy of buses rumbles down the California highway.

Like the rest of the Japanese community, he and his parents were given orders to bring what they could “hand carry” and to meet at an address which ended up being St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Los Angeles. Now, they are a few minutes away from what would be their new 6-month home, the Santa Anita racetrack.

The child didn’t think too much about the journey or the unusual life he would soon experience. The makeshift army barracks he and his parents dwelled in, the chain-linked fence that enclosed them, and lack of privacy in bathrooms and showers became a normalcy for him. Transferring from camp to camp with no permanent home, George Nakano would not understand why he, his family, and other Japanese were under constant surveillance. He did as he was told and rolled with the punches.

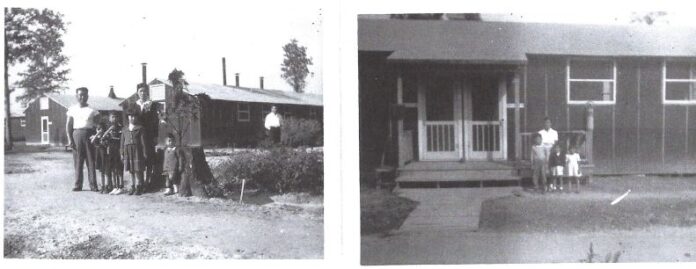

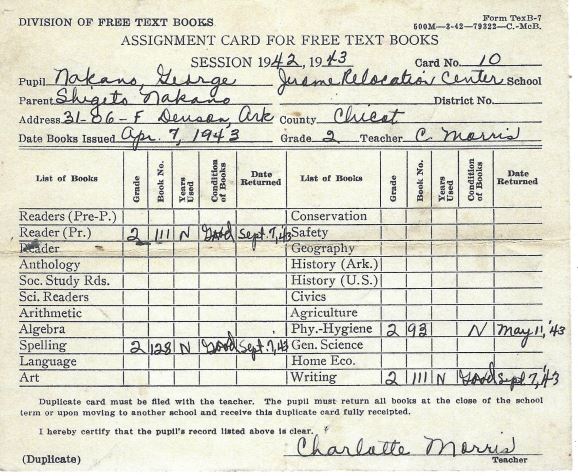

He and his family were eventually taken to Jerome, Arkansas, a prison camp where they spent about a year under similar conditions as the Santa Anita site. Surrounded by forestry with nowhere to escape, the camp in Jerome had a fairly lax security around the perimeter, with some guard towers overlooking the camp and entrances. George’s father became the camp carpenter building cabinets and playground equipment out of the abundant wood and lived a moderate life for the next 11 months. Still, even with the occasional arguments about their living situation and frustrations toward the unruly Order 9066, it wasn’t a bad experience — at least compared to the final years of their incarceration. As a result of his parents’ response to the “loyalty questionnaire,” the Nakano family was sent to Tule Lake for the remainder of their concentration period, 2.5 years.

LATEST STORIES

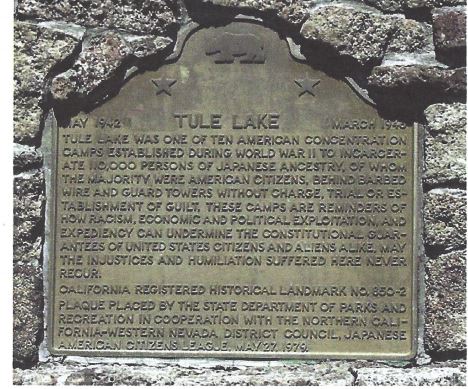

Stepping into Tule Lake’s campgrounds, George immediately felt insurmountable pressure. “There is a tension of the administration versus the so-called inmates being watched all the time. And then there is always that tension within the group that I guess some people feel that the group leader is not responding adequately to a given situation. That became more clear when I started reading about Tule Lake — some of the things that went on,” George described in a Densho interview.

Having lived in camps for the last 2 years of his life, George thought he could acclimate to the new environment like he did in Santa Anita and Jerome. But no matter how much time passed, he always craved Jerome’s watermelons and tsukemono, its makeshift wooden playground, and the sense of freedom, lax security, and community in the previous camps. With a sneaking suspicion that prisoners snuck in the equipment, George and other child inmates tried to relieve the pressure through sports like baseball, football, and kendo. But on scorching summer days, it was difficult to find shelter from the heat. Hiding in uninsulated barracks was an option, but the hot air seeped through the seams of the shack like walls, and the families cramped inside only made the rooms stuffier.

Luckily, there was a small canal with trickling water just along the fences inside the camp. Sufficient enough for small children, George and fellow child prisoners ran into the canal like suburban 1940s middle class children would run through sprinklers on a summer day. It was only minutes later when a shout from the guard towers and a shiny rife aimed at their bodies would destroy that surreal fantasy, snapping the children back to their unprivileged lives. “There’s no recreational facilities in a camp, so as kids you’re going to look for things you can do,” George told AsAmNews. Childhoods were locked away and unfulfilled, only adding to the distress at the camp.

Tule Lake’s food was scant in quantity and lacked in taste. Food intended for prisoners didn’t trickle down to them, rather, went to a black market. Protest leaders were arrested and sent to Bismarck, North Dakota, one of the coldest cities in the States. Turmoil between pro-America and pro-Japanese prisoners arose. Stabbings, a fire igniting the auditorium, and a jail sweep kept people in check.

“The Arkansas scholars, they said, we should not be called ‘internees,’ we should be called ‘inmates’ by the true definition of what the camp was,” George said in a Densho interview.

Frustrated, angered, and traumatized from the government’s harassment towards them and their kids, George’s parents signed up to return to Japan once the war was over. They also sent George, along with his younger siblings, to Japanese school in the camp. Though, once the war finally concluded and George’s mom informed her sister of their intent to go back to Japan, she urged the family to not go since the country was devastated and war ridden. After reading the letter, his parents were convinced to stay in America and reclaim their citizenship.

After inmates trickled out — most returning to Japan — the Nakanos were one of the last remaining families in Tule Lake. The process for reclaiming their citizenship was an arduous process filled with paperwork and copious amounts of waiting. But with the help of attorney Wayne Collins and after what felt like a long stretch of time to the 10-year-old George, the Nakano family and other Japanese Americans who stayed behind were regranted their citizenships, leaving Tule Lake in 1946. Upon hearing the news, George’s parents became elated and excited. After four arduous years of mistreatment and uncertainty, they could finally return home. However, the giddiness was short-lived.

With little money, homeless, and jobless, it was difficult to reintegrate back into society. The Nakano family, now with three children, were constantly on the move. First, they lived with relatives for three months in East LA in Mott Street, then moved to Norwalk for three years under company housing after his father started working for a railroad company. But as the tenuous labor strained his father’s health, they moved to a different part in Norwalk for two years where his parents worked as tenant farmers until his mother fell ill and was unable to continue working. At last, they found themselves back in East LA. Reminiscent to their concentration period, the five person family crammed into a dilapidated one bedroom apartment, eight houses from the Dolores Mission, the poorest Catholic Church in LA County. With termite infestations in the summer and leaks in the winter, the rundown Boyle Heights apartment was their home for seven years.

Along with the vibrant Jewish, African American, and Hispanic community, Boyle Heights teemed with impoverished Japanese Americans who freshly migrated out of camps. It was one of the most diverse neighborhoods in LA at the time. Many Japanese Americans chose this location for its convenient access to Little Tokyo and though destitute in quality, housing was cheap. The community grew big enough to establish a Japanese church equipped with a dojo and held annual Japanese cultural festivals since the 1940s. The local community even established a Japanese hospital which treated a majority of the Japanese living in Boyle Heights and Little Tokyo.

“Wherever you have a higher concentration of [a certain] population, you will always find churches and temples as well as a community center,” George told AsAmNews.

But even with a fairly nice community, the gang infested, graffiti filled neighborhood was not an ideal place families wanted to be in. Streets were lined with cars that hogged parking spaces, litter filled sidewalks, and unkempt roads. George and the rest of his family wanted to move out quickly.

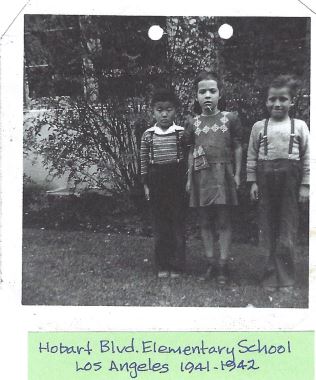

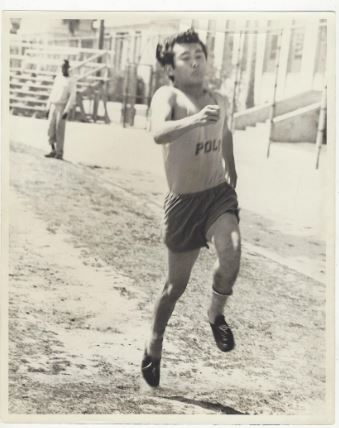

During this time, George attended Hollenbeck Junior High School while being active in the Japanese American community. Balancing out track and field, trips to Little Tokyo for Japanese and judo classes, and eventually transferring from Roosevelt High School to John H. Francis Polytechnic High School and taking up a part-time job at an auto-shop near Shrine Auditorium, George was a diligent student who sought to help his family and community in any way he could. Even with a great track record both on the field and in school, he was hindered from pursuing his passion; math.

George was passionate about his curriculum and sought a challenge. He wanted to take algebra but his teacher failed to provide a recommendation for him. Despite being one of the top two students in math class and obtaining A’s in every class, George had one disadvantage; he was a minority student. Before the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, Holleback and LAUSD schools had an unwritten policy to direct minority students to vocational school.

Dejected, he moved onto other matters and turned to his community. There was a sense of safety, community, and solidarity within other Japanese kids and POC. It especially helped that he attended diverse schools with Japanese, Black, and Jewish kids. These kids eventually formed clubs within themselves which provided emotional stability while serving the local community. Amidst graduation, George and his friends created the Constituents where they played sports and supported each other while raising money for local businesses or providing services for Children’s Homes.

“Being a youngster that had just come out of camp, we just didn’t trust a lot of White people. They were the ones that threw us into camp,” George told AsAmNews.

George continued these acts of service even while attending trade school and working full time as a Radio-TV servicer in Hollywood. Though, once the Nakano family was granted $1200 from the Claims Act, the family moved out of the bleak apartment into a proper home in Gardena in 1956, making George’s commute to work difficult. He joined the R&D sector at Hughes Aircraft while also volunteering his free time to community work. On weekdays he performed problem solving tasks and utilized math and on weekends he worked alongside younger students and kids. Watching the younger generation develop, grow, and realize their full potential, George finally found his calling.

“Given what happened to me in junior high school, when I was in junior high school, I chose to go teach at Jordan High School in Watts to help students go to college,” George told AsAmNews.

With Hughes Aircraft offering to pay for 75% of George’s university tuition, he immediately enrolled in El Camino College to complete his lower division classes and graduated with a Bachelors of Science in math from CSULA. He then transferred jobs to becoming a math teacher at Jordan High School and worked his way up to an administrator in the Inglewood Unified School District. He was recruited to implement a multicultural program for the entire school district which helped George land a position as an assistant principal.

But once more, George’s local community called for him. Two attorneys approached him asking to run for city council because they were in need of a Japanese American representative. He retired from teaching and pursued one last calling to serve his community. With the support of the Torrance Homeowners Association, he was elected to be a part of the City Council in 1984 and 15 years later, he became the first Torrance resident elected to the California State Assembly in 1998.

Serving for the Torrance community, George knew the city had an abundance of Japanese Issei (immigrants) and Nisei (first generation Japanese Americans) dating back before the war. This was largely because of the Alien Land Law; the South Bay area was one of the few areas where Issei were permitted to lease property. As a result, there were many Japanese American nurseries and farmers in the area.

The neighborhood is also located just south of Downtown Los Angeles, providing easy access to Little Tokyo. Although after the war, many of these nurseries vanished as a result of the concentration camps and lost property. Still, the community remained at large following the war. In part, the South Bay is close to Long Beach, a port city, and it still remains a convenient neighborhood for Japanese businesspeople.

Jack Rodman, a Leventhal managing partner, told LA Times, “The attraction in Palos Verdes is the ranch-style homes, which are more like a Japanese home–single-story, spread out. The ocean is very attractive. And Palos Verdes is a little less expensive than the Pacific Palisades, Bel Air and Brentwood.”

But a major factor in Torrance’s current Japanese American population is largely due to Toyota’s presence, the jobs they created, and the fact that jobs were bilingual (Japanese and/or English) was a major appeal. The Torrance Asian community became so prominent to the point they were divided by city lines and boundaries. George unified this community by redrawing the Torrance’s assembly district into a single district, shaping the city’s borders to what it is now.

Along with Toyota, Honda followed suit a decade later, attracting more Japanese workers to the city. George capitalized on this feat as well. He established the Office of Economic Development in 1992 which sought to attract and retain high tech and manufacturing companies. With the attraction of these companies comes the influx of highly educated people with disposable income. The people who drive the service industry, go to hotels, restaurants, and commercial stores. He knew they would shop at the Del Amo Fashion Center — the largest shopping center in America at the time. “If you have a safe city, which we did, during lunch and right after work, they’re not gonna drive home and shop in their hometown. They’re gonna shop in Torrance,” George told AsAmNews.

He made significant efforts for the establishment of Torrance’s Graffiti Abatement Program in 1988, keeping the city clean, safe, and attractive. Growing up in Boyle Heights and teaching in Watts, George knew how to deal with vandalism, “As soon as a graffiti goes up, you gotta get it out; graffiti attracts graffiti,” George told AsAmNews.

Reflecting on his time in Boyle Heights and the living situations he experienced throughout his life, he knew what the Japanese community sought and the type of environment families wanted to be in; he knew how to attract and maintain the local community. With Torrance being a neighborhood filled with cultural businesses, temples, community centers, safe, and clean, George played a large role in Torrance’s attraction for both people and overseas businesses.

Despite being the fourth largest city in LA County, Torrance had the second highest sales tax revenue in 1997, just after LA. George also secured funds to develop the Japanese Pine Wind Garden, embellishing the city in traditional Japanese landscaping and architecture. Finally, he honored Torrance residents who gave their lives in war by obtaining state grants and constructing the Veterans Memorial Wall.

“For me, those are the exciting parts about being in office. To come up with ideas to improve things. That’s why people should be in office, to improve and solve problems,” George told AsAmNews.

Little Tokyo is still a popular attraction for residents, the Japanese community, and tourists. It is still equipped with the defining features of a proper Japantown: temples, churches, community centers, cultural events, local Japanese shops, and even the Japanese American National Museum. Yet, I have to wonder where the city’s direction is headed. Legacy shops are gradually being replaced by businesses that have no relation to the local community. Gentrification is slowly transforming the historic neighborhood into a bland utopian-style city where former locals are forced out of their homes once more and only people making 6 figures can afford a studio apartment.

In the trajectory the city is going, I fear I’ll no longer recognize the Little Tokyo I grew up with. The local restaurants, gift shops, traditional sweets, and community I interacted with all might be gone by the time I visit again. Perhaps I’ll see several smoke shops, hipster-esque cafes selling $8 matcha lattes, and restaurants run by lavish businessmen who have stayed in Roppongi Hills, Toranomon Hills, and Ginza for a few months (basically experts on Japanese cuisine).

Perhaps the former community will migrate to another area of the city and start anew, making history once more until the colonization cycle of gentrification and capitalism repeats. Or they all move to Torrance and make the neighborhood flourish with more authentic businesses. Learning more about these communities and speaking with several community centers, I realized as long as people like George serve the community, the community will never truly die. Though gentrification may take hold of culturally rich neighborhoods, the people, their memories, and firsthand experiences are things that can’t be replaced.

Retired and energetic, he meets with friends from former high schools and clubs every so often, gathering for picnics and casual meetups reminiscing about the old times while providing updates of children and grandchildren. He sometimes thinks about his old apartment in Boyle Heights. Sure there were cosmetic upgrades, but he doubts the interior changed much, especially since a sea of cars still overflow the narrow streets in the neighborhood. But, he doesn’t have to worry about that anymore. Now, George Nakano, 88, sits comfortably in his living room alongside his wife as he stares out the window of his roomy, well furnished, and comfortable house.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.