By Kiyomi Casey

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo– a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo is one of four surviving Japantowns in California. It was formed around 1885 as Japanese immigrants began opening restaurants there. Today it spans about five blocks that contain Japanese restaurants, shops, and landmarks. Little Tokyo serves as a cultural hub for Japanese Americans. However, less than 10 miles north in what is now southern Glendale, was one of around 40 lost Japantowns in California.

Southern Glendale and parts of Atwater village used to be a small agricultural town called Tropico. The name came from the Southern Pacific Transportation Company, because in 1887 they named their station in the area Tropico. According to Survey LA, the Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey, Tropico “became the first recorded place in Los Angeles where Japanese worked on farms”.

The first Japanese laborers arrived around 1899, and many followed in the coming years. Japanese farmers in the area mostly grew strawberries. According to Immigrants in Industries, a 1907-1910 series of reports by the United States Immigration commission, “In 1904, at Tropico, 29 Japanese tenants were leasing 155 ½ acres for the growing of berries…Two years later the number of leases had more than doubled while the acreage lease was 424 ½.”

A few years later damaging frosts occurred and many White landowners withdrew from the strawberry business. Some Japanese moved away from Tropico, often to Glendale and Burbank, while others turned to vegetables as their new crop.

Tropico was a short-lived city. It didn’t become officially incorporated in 1911, and residents voted to have it annexed to Glendale a few years later in 1918. However, the Japanese community continued in Glendale. According to the National Park Service, Japanese in Glendale worked as gardeners, or domestics, and some began opening floral shops.

“By 1939-40, there were 64 Japanese retail florists in Los Angeles City. In addition, there were 13 in Glendale, 10 in Pasadena, 5 in West Los Angeles, and a number of others in scattered districts around the city.”

In 1942, Executive Order 9066 was signed, authorizing the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Japanese families in Glendale had to abandon their lives, leaving their homes and businesses without knowing if they would be there when they returned. Those who were unable to move inland were forced into incarceration camps. Eventually, the government made exceptions for those who would pledge their loyalty to the United States and serve in the military.

Despite the discrimination against Japanese Americans by the United States government, a Japanese Glendale resident decided to fight in the U.S. Army and became the first Japanese American to win the Medal of Honor.

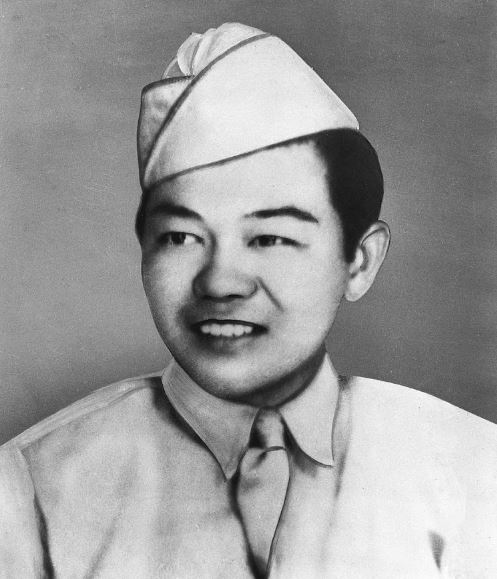

Glendale-born Japanese American received the Medal of Honor

Go for Broke means to risk everything to win big. Originally Hawaiʻi slang used in gambling, this became the motto for Nissei (second-generation Japanese American) soldiers during World War II. Private First Class Sadao S. Munemori, the first Japanese American to be awarded the Medal of Honor, embodied the meaning of Go for Broke.

Munemori was a second-generation Japanese American, born and raised in Glendale, CA. On Aug. 17, 1922. He became the fourth of five children born to parents Kametaro and Nawa Munemori, who immigrated from Hiroshima Japan. According to their archives, the City of Glendale reported that the family owned a vegetable farm near San Fernando Road and Glendale Avenue.

Munemori signed up for the US Army as a language specialist one month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was seeking a better life for his family after his father passed away. He formally entered the Army on February 11, 1942, when the military approved his enlistment. One week later, on February 19, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted Executive Order 9066 which led to the incarceration of around 120,000 Japanese Americans. This included the Munemori family, who were sent to Manzanar. Munemori did not go with his family and was sent to military training instead. He eventually worked his way into the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage.

While separated from his family, Munemori often wrote letters to his sister Kikuyo. According to the Smithsonian, in March of 1942, he wrote, “I got insurance…If I get killed after May 1’ 42’ Mom will get $80 a month for the rest of her life…I know I’ll come back from the war alive, but just in case they send you my ‘dog tag.”

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor Japanese Americans were reclassified to category IV-C, as they were viewed as aliens ineligible for service, and no new Japanese Americans could sign up to serve in the military with few exceptions. However, in January 1943, the U.S. Army restored the right of Japanese Americans to serve. Many wanted to prove their loyalty to the United States, and around 33,000 Japanese Americans served in WWII. Around 6,000 served as translators and interpreters, but most served in segregated units known as the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Munemori left the Military Intelligence Service Language School when he heard of the formation of the 442nd RCT. He accepted a lower rank in order to transfer. In 1944 he was sent to Europe as a replacement soldier for the 100th Infantry Battalion. Other snippets of Munemori’s letters to his sister, shared by the Smithsonian showed how much he struggled during the war.

“I certainly hope that this war would come to an end so we could all be together again. … I miss Japanese food so much, I have nightmares at night sometimes.”

“Just say a small prayer for me every now and then and keep your fingers crossed. Give my love to Mom for me.”

In April of 1945, Munemori fought in Northern Italy with the mission to penetrate the German’s main defensive line known as the Gothic Line. Munemori stepped up when his squad leader was wounded, taking charge. While making his way towards the safety of a shell crater where two of his men were taking cover, a grenade hit Munemori’s helmet and rolled towards the crater. Rather than running for cover, Munemori dove onto the unexploded grenade and sacrificed his life for his two comrades.

Munemori’s fellow veterans remembered him well, not just for his sacrifice, but his value as their friend. The Puka Puka Parades, a newsletter published by the 100th Infantry Battalions Club collected a few letters from fellow veterans remembering Munemori.

In a letter published in 1985, Stanley Izumigawa called Munemori “very friendly, outgoing and accepting”.

A memory that stood out to Izumigawa was when they found candy around Carrara Italy and decided to give it to children.

“Suddenly, it seemed, kids were coming from everywhere, yelling, push clawing for the candy. I don’t know what happened afterward. We just dumped the candy on the street and ran. I don’t recall what we said to each other on the way back, but the experience is one I always remembered. It wasn’t long afterward that Spud was killed in action.”

Munemori was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration. His mother was presented his medal at Fort MacArthur, CA on March 13th, 1946. The Pacific Citizen reported on his heroism.

“A squad leader in the 442nd Combat Team, the Japanese American unit which distinguished itself throughout the Italian campaign and later in Germany, Private Munemori single handedly destroyed two German machine guns, killed three and wounded two of the gunners and then gave his life by hurling himself upon an exploding grenade to save the lives of two comrades last April in Italy” Pacific Citizen Vol. 22 No. 11 March 16, 1946.

While over 800 Japanese Americans were killed in action, and over 33,000 showed their patriotism and loyalty by risking their lives to serve their country during WWII, Munemori was the first and only Nisei soldier from WWII to receive the Medal of Honor at the time. It took fifty years before Congress asked the Army to review over 50 Asian American Distinguished Service Cross recipients, the second highest military decoration, for the Medal of Honor.

On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded the Medal of Honor to 22 Japanese American soldiers from WWII. The majority had served with the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

“Rarely has a nation been so well-served by a people it has so ill-treated. For their numbers and length of service, the Japanese Americans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, became the most decorated unit in American military history.” Clinton stated while presenting the awards.

Munemori continues to be remembered and honored for his sacrifice in the city he grew up in. On December 9, 2023, Glendale publicly unveiled Sadao S. Munemori Memorial Square at the intersection of Isabel Street and Broadway. The square recognized him as a local hero. In a city press release the Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles Kenko Sone shared what he hoped the impact of the square would be.

“Sadao S. Munemori Square will provide a lasting landmark of the Japanese American presence in Glendale and inspire all who pass through the intersection of the heroism and self-sacrifice of Mr. Munemori and the resilience and remarkable contributions of the entire Japanese American community. The Government of Japan supports various initiatives aimed at strengthening the relationship between the Japanese American community and Japan. I hope the square naming will encourage Japanese people to visit Glendale and to understand the impact of Japanese Americans in various places, including in Glendale,”

Munemori is also honored at the Memorial Wall at Broadway and N. Isabel St., next to Glendale City Hall. Sadao S. Munemori’s name can be found at the very bottom of the World War II Memorial, with the medal of honor engraved to the left.

Japanese Culture in Glendale Today

While there is hardly a trace of the Japanese farmers or florists in Glendale, Japanese culture remains through the sister city’s relationship with Higashiosaka, Japan. In 1974 the two cities worked to build the Shoseian Teahouse, a traditional Japanese Teahouse in North Glendale. The teahouse was designated a Landmark building by the Glendale Historical Society.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

Mahalo for the informative article about how Tripico became part of Glendale and about the first recipient of the medal of Honor, Sadao Munemori; however, your following statements need to be further clarified:

• Many wanted to prove their loyalty to the United States, and around 33,000 Japanese Americans served in WWII. Around 6,000 served as translators and interpreters, but most served in segregated units known as the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

CLARIFICATION: The number 33,000 refers to all those who served in WWII and up to the start of the Korean War in 1950. The accurate number of those who served in the 100th Battalion and 442nd RCT is 10,000. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Japanese%20Americans%20in%20military%20during%20World%20War%20II

• On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded the Medal of Honor to 22 Japanese American soldiers from WWII. The majority had served with the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

CLARIFICATION: On that date, President Clinton awarded the Medal of Honor to 22 Americans of Asian descent, of whom 20 served with the 100th Battalion and 442nd RCT. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Congressional%20Medal%20of%20Honor%20recipients