By Dhanika Pineda

(Editor note: This story is a joint project between AsAmNews and AARP and is funded by AARP)

Paurvi Bhatt is alone.

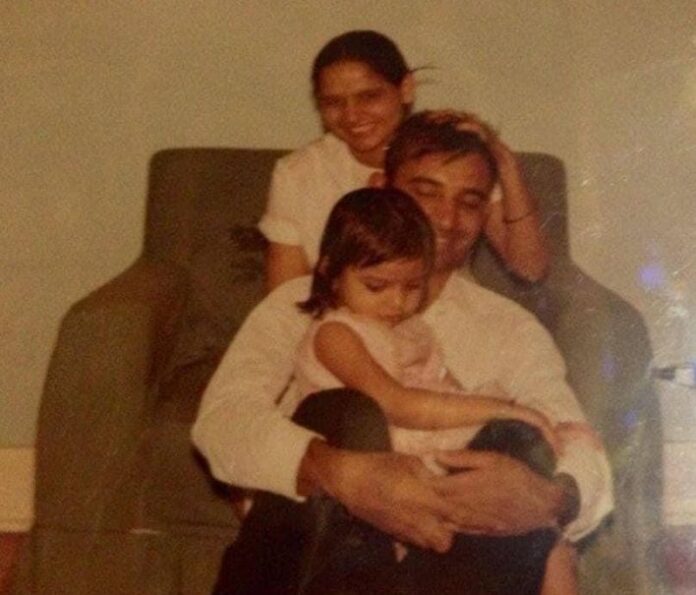

“We were, you know, a combined package,” she said, reflecting on her time as a caregiver for her parents. “That wasn’t always easy to navigate in terms of finding a partner for myself and creating the conditions for me to expand our family with a partner and children. So today, it’s just me now.”

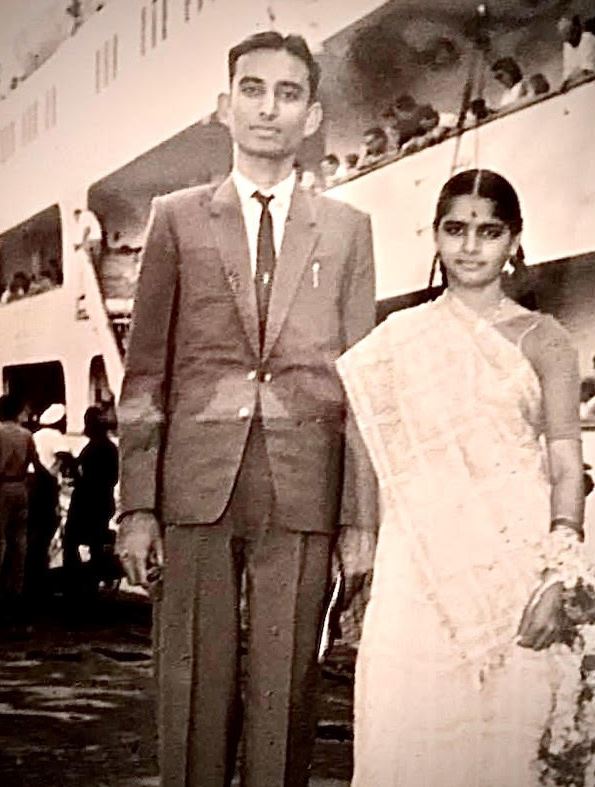

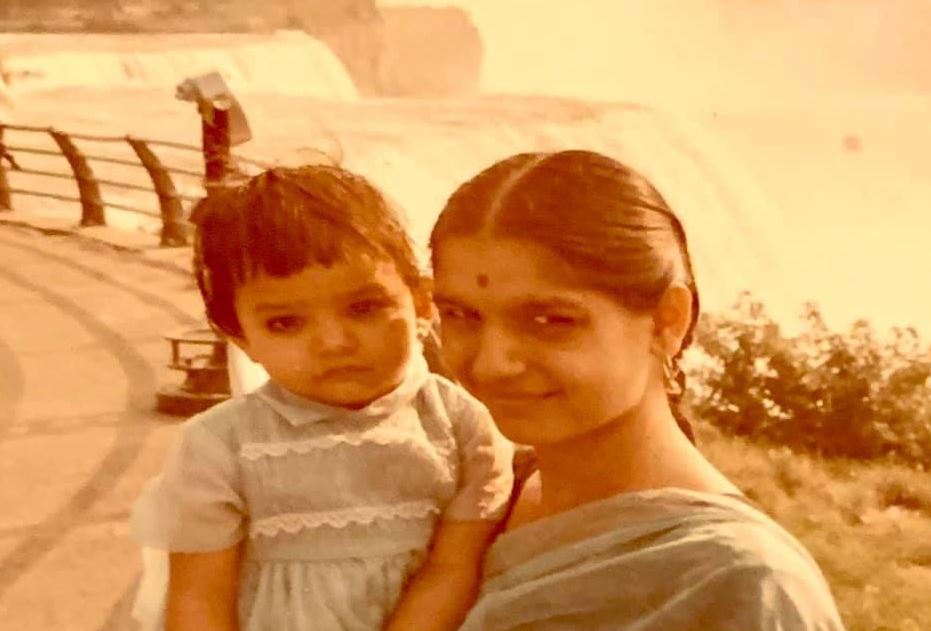

Harshad and Rekha Bhatt immigrated to the states from India in the early ‘60s. Harshad came first on a ship in 1963, until Rekha joined him in 1965. The couple, brought together through an arranged marriage, soon brought Paurvi into the world. They took care of her, and when the time came, she took care of them.

“Because I was an only child and a daughter, my priorities became really clear, really fast that their wellbeing was associated with mine,” she said. “I don’t have children, and I don’t have siblings, so it sets up another chapter of ‘How do we find care and support?’ It is one of those evolving stories of aging for first- and second-generation immigrants.”

Rekha Bhatt was diagnosed with cervical cancer when Paurvi was just three years old. Harshad quickly became a caretaker for his child and wife. He faced his own diagnosis of early onset dementia almost 25 years later at just 58 years old.

At 57 now, only a year younger than her father was when he was diagnosed, Paurvi can imagine the fear her father must have felt facing such an affliction.

“I was 28 when he was diagnosed. So while I navigated my career, I was — unbeknownst to me — also navigating how to take care of the situation that both my parents were in,” Paurvi said.

Navigating the latter was like steering a ship without a compass. Without the resources to join their children in the states, Paurvi’s grandparents remained in India. She watched Rekha and Harshad lose their own parents from afar. At the young age of 28, even as a public health professional Paurvi didn’t have a blueprint for the familial caretaker she needed to become.

“They didn’t see the aging process unfold for their parents every single day, because it was happening someplace else and that has its own sets of pain… [My parents] didn’t necessarily recognize how aging would unfold for them,” she said. “So they might have been aware, but didn’t necessarily see in a practical sense what that would mean here in this country, and nor did I in watching.”

There are many difficulties that come with the adjustments to becoming a caretaker — emotional, social, and even financial strains are faced by nearly 48 million adult-caregivers in the U.S., according to a 2020 report by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). AARP research also shows that nearly 80% of adult caregivers face out-of-pocket caregiving related costs, with an estimated annual spending of $7,242 or 26% of the caregivers income.

Fueled by personal experience, Paurvi is now an outspoken advocate for providing more resources for caregivers, including financial compensation. From the time of caregiving to times of grief, Paurvi believes in the necessity of supporting familial caregivers whether that be through reimbursement of medical training from the healthcare system or grief and bereavement support from the workplace.

“There came a point in time, even when I was a long-term caregiver, that I knew that I needed to be closer to home to help be a part of delivering care at home. I never once thought about it from the fact that I’m someone who knows healthcare. I just did it because I was a daughter in a family where English was a second language, and it’s something that I just knew I needed to help with,” she said. “In order to do that, step away from work and come home, we need a better support system in place that has care in mind.”

Still, it takes more than money to create a good system of care. According to Paurvi, it also takes an appreciation of culture and an understanding of the need for inclusivity.

“There were so many things that didn’t even occur to me that didn’t exist until I was asking for it,” she said. “There are cultural barriers that exist in the health system, and they are problematic.”

When it comes to delivering the best care possible at home, Paurvi sees the importance of understanding and implementing cultural nuance. From home-visiting medical professionals observing cultural practices like removing one’s shoes before entering a home to ensuring that a diverse array of healthy food options become available to patients who may not be used to a Western diet, the mainstream healthcare system can adjust to each patient’s cultural needs.

“If we are trying to deliver care at home, things like food become very important, and we see it from the minute someone’s in the hospital all the way through to discharge and coming home,” Paurvi said. “Of course, healthy foods exist in every ethnic arena, our recipes in this country have become much more diverse. We have to provide those offerings for people.”

For Paurvi and her mother, one of those foods was Kitchari, an Indian porridge of rice, lentils, and plenty of healing spices. While the dish might be a popular staple in Indian cuisine, it’s not often offered by caretaking delivery services.

Paurvi is a firm believer that familial caregivers can deliver some of the most compassionate care possible.

“We probably have plenty of people here who would be more than willing to do this work if it was actually set up to be a career. I mean, imagine a world where, if you started working at home in providing healthcare and you wanted a career in healthcare, you had a subsidy to be able to become a nurse if you wanted to. You had subsidized entry into education and accelerated or subsidized entry into medical school,” she said. “Imagine what that would mean, how many people would do it and think about the compassionate care that would immediately transform the system, because everyone started at the bedside. At home.”

With the most compassionate care often comes the strongest form of grief. Paurvi, whose caregiving arc lasted from her 20’s to her 50’s, is still processing the grief of losing both of her parents.

“Grief begins before the life ends,” she said. “Anticipatory grief is extended with caregiving, and especially consecutive caregiving. To be open about grief is key, but it can be hard and that’s okay.”

After losing her father, Harshad, on December 3, 2011, Paurvi continued to live with and care for her mother for 13 years. Rekha Bhatt passed away on February 24, 2022.

“When the caregiving is done, where does the care go?” Paurvi mused.

Perhaps the care goes back to the caregiver. Through friends who send thoughtful flowers on her mother’s one year death anniversary. Through conversations near Diwali keeping alive the light of her loved ones who have passed on. Through the lighting of the crematorial fire, being part of what it takes for them to be physically gone and released from the Earth. As Paurvi herself said, through “the fact that they are gone, and you were the best of them to move forward.”

Paurvi Bhatt is not alone.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.