By Sudip Bhattacharya

“I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children and seen them most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

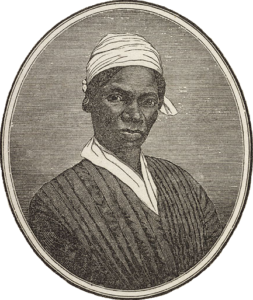

Sojourner Truth spoke those words to an audience of White women and men at a convention in 1851 at Akron, Ohio, as explained by Angela Davis in Women, Race, and Class. Truth, who was an African American woman, expressed her frustration dealing with the racism from White suffragettes and the chauvinism she received from the men. She understood that her experiences as a woman of color were constantly at risk of being forgotten and overwhelmed.

Black and Brown women continue to face a system that was designed to control and dehumanize them. On August 1, news broke of the fatal police shooting of 23-year-old Korryn Gaines. Gaines, who was African American, was allegedly in a stand-off with police, until she was shot and killed. Her 5-year old son was wounded as well. Many remain suspicious of explanations provided by the police over what happened, especially since countless incidences of police brutality against unarmed Black men and women have been caught on video.

Ultimately, the death of Gaines was heartless and should fill anyone with rage. But also, it reminded us of how the harassment and oppression that many Black and Brown women experience is overlooked and condoned, even by men of color. For every major protest in solidarity for victims like Eric Garner, and support for actors such as John Cho, there remains distressing silence for women named Sandra Bland, Dee Whigham, and Purvi Patel.

Too often men of color are solely focused on combating racism. Too often we shield ourselves from criticism by redirecting blame to White Supremacy, claiming that the most important goal is to somehow invest in our so-called lost “masculinity”. Most importantly, we fail consistently to understand the complexity of being a woman of color in the U.S.

“U.S. Black women’s efforts to grapple with the effects of domination in everyday life are evident in our creation of safe spaces that enable us to resist oppression, and in our struggles to form fully human love relations with one another, and with children, fathers, and brothers, as well as with individuals who do not see Black women as worthwhile,” writes famed sociologist Patricia Hill Collins. “Oppression is not simply understood in the mind—it is felt in the body in myriad ways. Moreover, because oppression is constantly changing, different aspects of an individual U.S. Black woman’s self-definition intermingle and become more salient: Her gender may be more prominent when she becomes a mother, her race when he searches for housing, her social class when she applies for credit, her sexual orientation when she is walking with her love, and her citizenship status when she applies for a job. In all of these contexts, her position in relation to and within intersecting oppression shifts.”

As similarly detailed by activist/academic Angela Davis, Black Women continuously confront levels of unjust power.

“The coupling of sexism and racism was mutually strengthening,” she expresses, later adding in Women, Race, and Class, “Black women had been more than willing to contribute those ‘clear powers of observation and judgment’ toward the creation of a multi-racial movement for women’s political rights.”

Despite the betrayals, there were always Black women who strove to unleash the potential of the human spirit through the dismantling of racial, gender, and class hierarchy. Davis highlights Ella Reeve Bloor, who was born in 1862 and became a labor organizer who hitchhiked all across the U.S. up until she was 62. She was “the heart and soul of untold numbers of strikes” and “in other parts of the country, miners, textile workers and sharecroppers were among the workers who benefited from her astounding oratorical talents and her powerful skills as an organizer.”

It has been women of color, from Bloor to Grace Lee Boggs, from the protesters at Stonewall to Alicia Garza and fellow co-founders of Black Lives Matter, who risk the most and done more than anyone in the fight against injustice. It has been the voices of Shirley Chisholm, Kshama Sawant, and Pramila Jayapal that shake the halls of power.

As a South Asian American cis-gendered man, this realization hit me this past year as I began my PhD program at Rutgers and in the process, asked more from my friends and family about their thoughts and perspectives as women of color. I am fortunate to know a diverse circle of mostly Black/African American, South Asian American, and Southeast Asian American women who work in international development, law, education, refugee orientation, doctoral programs, and even marketing. Listed are some of their insights on identity, feminism, and the manner in which race and gender intersect.

Sarangi Iyengar:

“As noted by many before me, identifying as a feminist, while being a person of color, has its own challenges – most notably (1) the first 3 waves of the movement did not really account for the unique struggles of women of color and (2) women of color have often had to choose to either align with one movement versus another. If I could only identify with one movement, I would choose standing with people of color over standing with women – otherwise, I do identify as a feminist.”

Poulami Banerji:

“a left-wing progressive Indian American woman of color, I’m not quite sure “why” exactly, I think as I grow older I get a better understanding of how each of my identities gives me a specific set of eyes to analyze the world politically, socially, philosophically, and otherwise. I identify with these identities because I think each of them have a specific and significant impact in that analysis.”

Zainab Alam:

“Identities are multifaceted, and the terms I chose to represent my identity vary depending on audience and context. Sometimes my identities are hyphenated, for example, I see myself as a Muslim-American, and other times they are broader and hyphen-less, for instance, I also identify as a person of color. Prioritizing different aspects of my identity is something I do on a daily basis, and I would not limit my sense of identity by choosing only one or two aspects.”

Lizzy Krajan:

“Gender, race, class and sexuality may be intersectional but they are parts to a whole. They may be defined differently by members of society but I believe identity comes from a deeper level. Gender, race, class and sexuality are simplifiers and questions on a survey but they should not be used as reason to look down upon someone. The importance of these traits are defined by the carrier but in my opinion, no matter what traits you carry, you should be loved equally by your neighbor just as s/he loves her/himself.”

Keiana Smith-McDowell:

“The conversation about White and Black feminism is one I beg Twitter to stop writing about (mainly because these people only come out from the sky when someone like Beyonce says she’s proud to be Black or some sh*t) but like, there’s this element of classism that’s married to race when we talk about this divide. Why do White women make more money than Black women? Race. Why do White women make less than White men? Gender. Why do White people in general make more than Blacks? Class and race. Why do White women love to write think pieces on Michelle Obama spending more than they think she should on a dress, or why Beyonce shouldn’t talk about sexing her husband on records but don’t do the same when Lena Dunham says she stuck her fingers in her sisters vagina as a child? Class and race. And that’s not equality, it’s not the fundamental principle of feminism to scold by race, but it happens. Even the awkward girl construct in television is relegated to White girls with the exception of Mindy Kaling, but we never hear about talents like Issa Rae, why? Class and race. I may have gone off topic but the complexities of race, gender, class etc. is a conversation that can go on and on and on.”

Their answers reveal the layers of identity that exist and which can go beyond what we think we already know.

Keiana:

“To be completely honest, I’m not a fan of labels. There are things I know to be true about myself, I love coming of age fiction, I binge watch shows like Gossip Girl and 90210 so maybe I’m a fan of rich kid teen drama, I don’t have any defined political affiliation, and if you saw me, it’s evident that I am both Black and woman – but I don’t think those things define me so I don’t limit myself to identity in that way. Maybe it’s not the answer that you’re looking for, but I am literally just a spirit – living, breathing and trying daily to be better. I don’t wake up thinking I’m Black, woman, a Democrat, college educated etc. I wake up thinking about how can I contribute an ounce of positivity or my time to this world and when’s the next time I can take a nap, that’s it.”

Black and Brown men need to listen and learn. Our position in society may not be parallel to that of straight White men and yet, we still benefit from patriarchy. If we claim to believe in liberation from systems of domination, excusing sexism is not only hypocritical, but counter-revolutionary. Either we stand alongside women of color, or we admit that we never cared about true freedom and only wanted to replace White men at the top.

Frederick Douglas and W.E.B. Du Bois accepted their responsibility as allies. Aside from advocating for the abolition of slavery, Douglas championed women’s suffrage, protection for Chinese immigrants, and international unity. An ardent proponent of social justice, Du Bois connected his belief in women’s equality to anti-imperialism and fostering coexistence among POC, regardless of class status.

Recently, President Obama penned an essay in which he called himself a “feminist” and explained the importance of ending gender discrimination and stereotypes.

“We need to keep changing the attitude that raises our girls to be demure and our boys to be assertive, that criticizes our daughters for speaking out and our sons for shedding a tear,” he wrote in Glamour magazine, “We need to keep changing the attitude that punishes women for their sexuality and rewards men for theirs.”

So, it is essential for us, as Black and Brown men, to embody the ideals of feminism espoused by Bloor, Boggs, and Davis. This means confronting our male friends and family members, which includes telling them that what John Cho believes regarding Asian American women is embarrassingly wrong. This means taking apart colorism and socialized masculinity and in turn, marching for the lives of Gaines and Patel among others.

If you’re unable to muster up the courage, picture Truth in front of hundreds on that day in Akron, surrounded by angry faces. Imagine the anxiety, the nervousness that reverberated through her. She probably knew she wouldn’t live long enough to witness when all people, especially those of color, would be allowed to become their complete selves. And that perhaps, it would’ve been easier to spend the rest of her days in Canada. Instead, she poured her heart out and regardless of the pressures, she made sure to be heard above the din of classicism, racism, and sexism, to be more than an observer.

In fact, two years after the convention in Akron, as described by Davis in her book, Truth remained blunt in her interactions with others.

“I know that it feels a kind of hissing and tickling to see a colored woman get up and tell you about things and Woman’s Rights. We have all been thrown down so low that nobody thought we’d ever get up again; but we have been long enough trodden now; we will come up again, and now I am here.”

AsAmNews is an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. You can show your support by liking our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/asamnews, following us on Twitter, sharing our stories, interning or joining our staf

RE: men of color and feminism: As a woman of color and having endured sexism and racism, the conscious thing I chose to do to fight on a personal level was to educate my sons through my experiences and history. I also explained to my sons that men and some women would look down at them because of the way the treat women and that society was the reason they behaved that way. I asked them to continue my legacy by teaching our future.