By Alice Wong

Guest Blogger

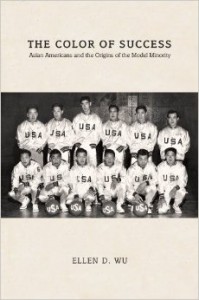

note from the editor: This is the first of a 2-part interview with Dr. Ellen D. Wu (pictured left), assistant professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is the author of the upcoming book, The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority, which gives a historical examination of the ‘Model Minority’ in 20th century America. This first part of the interview with guest blogger Alice Wong(pictured right) discusses the history of the Model Minority and how it impacted Asian Americans.

note from the editor: This is the first of a 2-part interview with Dr. Ellen D. Wu (pictured left), assistant professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is the author of the upcoming book, The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority, which gives a historical examination of the ‘Model Minority’ in 20th century America. This first part of the interview with guest blogger Alice Wong(pictured right) discusses the history of the Model Minority and how it impacted Asian Americans.

Q: In short, how would you describe the term ‘model minority’ to someone who has never heard of it before?

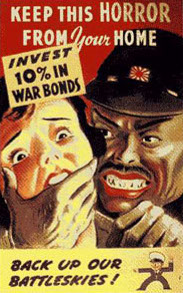

I would start by noting that the concept of the “model minority” is historically contingent—what it meant has changed over time in American history. During the period that I cover in the book (1940s-1960s), Americans came to consider Japanese and Chinese Americans as “model minorities” in very particular ways: they were peoples distinct from the white majority but lauded as well-assimilated, upwardly mobile, loyal and patriotic to the United States, exemplars of “traditional” family values, politically non-threatening, and what I call “definitively not-black” (that is, APAs did not seem to behave like African Americans). For people invested in delegitimizing the African American freedom movement, the “model minority” stereotype served as “evidence” that the United States was indeed a land of opportunity for all, including racial minorities.

Today when people speak of Asian Pacific Americans as the “model minority,” I think there is more of an emphasis on the upwardly mobile part of it, especially the APA presence in institutions of higher learning (the Ivy Leagues and such). The “Tiger Mom” is perhaps the most visible example of the “model minority” in current-day popular culture. There seems to be less attention to the “definitively not-black” aspect of stereotype nowadays; instead, the subtext is often about white folks being threatened by Asian Pacific American competitors in the marketplace and other venues where white privilege has historically been reproduced, mirroring the nation’s anxieties about China and other Asian/Pacific rivals in the global economy.

The “model minority” stereotype in the 21st century also differs from its post-World War II predecessor in that it encompasses a wider range of groups: not just Japanese and Chinese Americans but also Filipinos, South Asian, and Southeast Asian Pacific Americans.

Finally, for the uninitiated, I would underscore that many APAs have astutely pointed out the “model minority” stereotype is highly problematic, even though it is an ostensibly “positive” image. For one thing, it obscures lots of social issues and challenges that APA’s face, including poverty, mental illness, racial discrimination, and racially-religiously inflected violence.

Q: Lots of Asian American Studies researchers have examined the “model minority.” What’s new and different about your book?

You’re right—Asian American Studies scholars have devoted significant energy to scrutinizing the model minority stereotype and its implications. This is obviously important research. In contrast, The Color of Success is the first book to offer an in-depth look at the historical origins of the stereotype. The conventional story told in Asian American Studies is that a few (white) journalists single-handedly devised the “model minority” concept in 1966 to dismiss the claims of civil rights/black power activists—a narrative that implies that Asian Americans were simply victims of this process. But I found a much more complex emergence rooted not only the African American freedom movement, but also in the geopolitics of World War II and the Cold War. And, perhaps most importantly, I discovered that APAs were at the very heart of the process of becoming the “model minority.” The outcome—the elevation of APAs over other minority groups—was an unintended one, but APAs definitely worked to change their collective public image.

In some ways, it has served the purposes of Asian American Studies to downplay the role of APAs in creating the “model minority myth”—acknowledging that history would seem to undercut the very important project of interracial solidarity among people of color that runs counter to model minority ideology. But I want to suggest that uncovering this episode actually helps to overthrow the tyranny of the model minority by highlighting the political diversity of Asian Pacific America, past and present. If our problem with the model minority is in large part that it flattens our differences, a history that zooms in on the various strategies and actions APAs took to deal with racism in American life actually “unflattens” those differences. Let me add, too, that the book also includes stories of APA’s who criticized the production of the model minority stereotype as it was happening.

Q: Your book investigates the evolution of the model minority by looking at the history of Japanese and Chinese Americans in the mid-20th century. How has the model minority myth impacted other Asian-American groups?

Q: Your book investigates the evolution of the model minority by looking at the history of Japanese and Chinese Americans in the mid-20th century. How has the model minority myth impacted other Asian-American groups?

Since the 1960s, the “model minority myth” has folded in other APA groups. Keep in mind that the demographics and composition of Asian Pacific American changed drastically after 1965. That year, Congress passed a landmark Immigration Act that resulted in a virtual explosion of APA newcomers from places like India, Korea, the Philippines, and Taiwan. Many were highly-skilled and educated professionals who came to serve the needs of the US economy, which was increasingly becoming more knowledge- and service-oriented. To many observers, these new white-collar immigrants seemed to affirm the assumption that Asians were somehow “naturally” smart and socio-economically successful. After 1975, the model minority stereotype expanded even more to encompass Southeast Asian refugee communities—often lauded by watchers for their “strong traditions” and conservative family values. By the 1980s, major magazines and newspapers were praising all of these APA groups together as “America’s Super Minority.”

Q: You interviewed many notable Asian-Americans for your book-tell me about one person’s story in particular that you think more people should know more about.

One of my most treasured experiences in researching this book was getting to know Setusko Matsunaga Nishi. Dr. Nishi was a Nisei (second generation Japanese American) who was born in 1921 in Los Angeles. She lived an amazing life, all the more remarkable considering all the societal constraints faced by APA women of her generation. During World War II, Dr. Nishi took part in the “student relocation program” initiated by liberal white Americans who considered college a promising path to “assimilation” for the young Japanese American prisoners of the nation’s concentration camps. She earned her bachelors and masters degrees from the University of Washington in St. Louis in 1944. From there, she continued to Chicago, where she worked as an apprentice to the eminent African American sociologist Horace Cayton in what Nishi called “the business of race relations.”

In 1946, Nishi began her doctoral studies at the University of Chicago in sociology, all the while serving as a dedicated advocate for the tens of thousands of Japanese American “resettlers” who left the camps to start over in Chicago (and other places in the Midwest and Eastern US). She was one of the founders of the Chicago Resettlers’ Committee, now known as the Japanese American Service Center, a social service/welfare organization. Note that the federal government had strongly discouraged Japanese American resettlers from forming ethnic institutions, believing that such groups would hinder their “integration” (and disappearance) into the white middle-class. Dr. Nishi saw the harmful psychological effects of such an extreme position and pushed back, arguing that her community needed such support structures in the wake of the trauma of incarceration.

As a female academic, I cannot help but be awed that Dr. Nishi raised five children while writing her dissertation, “Japanese American Achievement in Chicago: A Cultural Response to Degradation.” From 1965 to 1999, Dr. Nishi was a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the Graduate School of the City University of New York. Through the decades—indeed, up until she passed away last year at age 91— she continued her pioneering research on Japanese Americans, especially the long-term effects of the internment experience. Meanwhile, she continued her social justice work on many fronts.

I was humbled and delighted to share my research on Japanese American resettlement in Chicago with Dr. Nishi (in which she appeared as a historical actor!). She kindly took the time to talk to me, read and critique my writing, and offer suggestions and encouragement.

You can read part two of this interview–a look at the model minority myth in the 21st Century here.

Additional information:

Dr. Ellen D. Wu is assistant professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington specializing in issues of race, immigration, citizenship, and nation through the lens of Asian American history. Follow Ellen on twitter: @ellendwu

About the author: Alice Wong is Staff Research Associate at the Community Living Policy Center at the University of California, San Francisco and a Council Member of the National Council on Disability. Follow Alice on twitter: @SFdirewolf